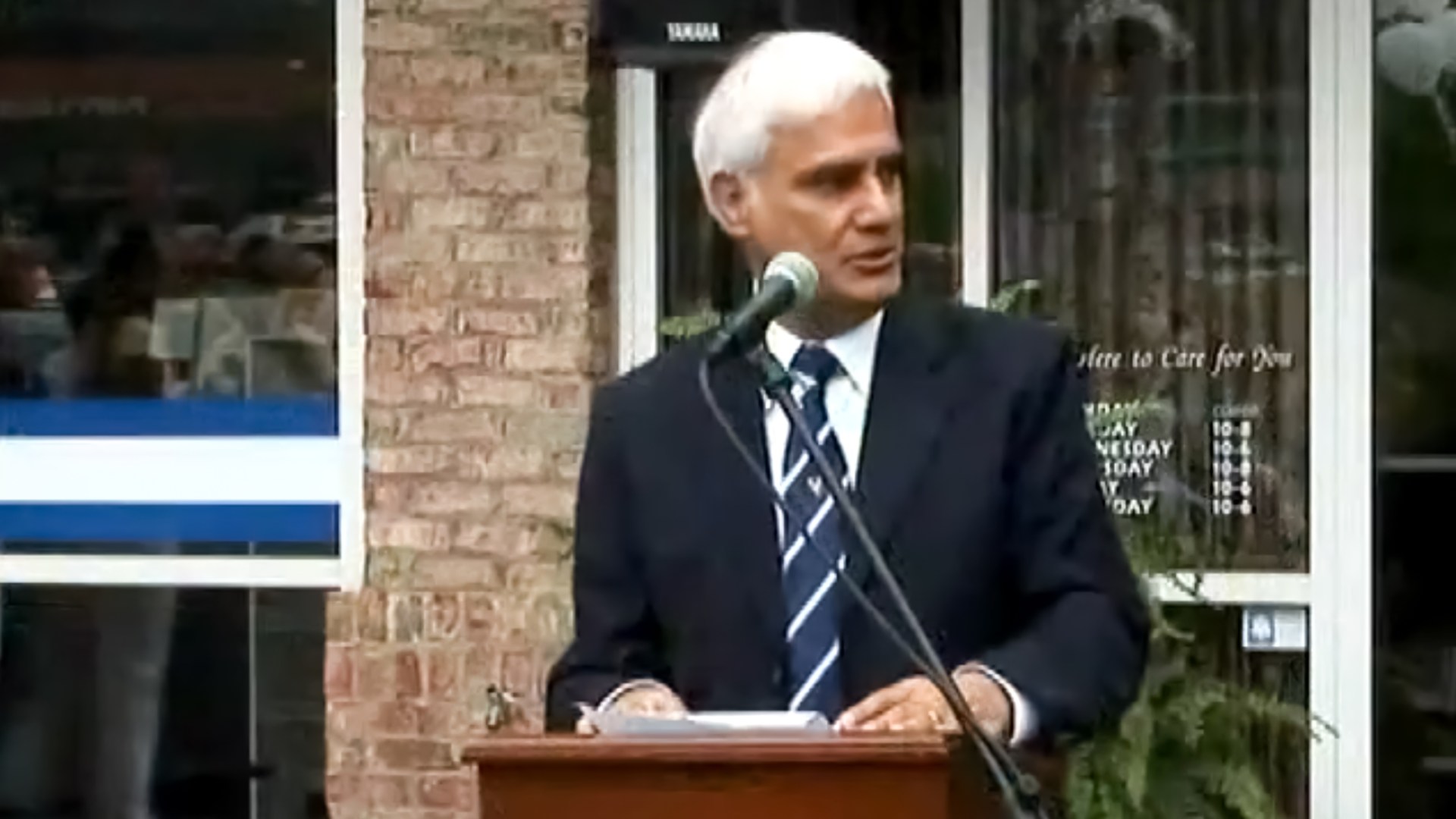

For months, California megachurch pastor Greg Laurie has spoken out against the instinct to politicize the coronavirus outbreak, preaching to his congregation to overcome outrage with outreach and look for opportunities to serve people who find themselves overwhelmed, scared, and angry.

But now he finds himself registering a positive test during one of the most politically heated moments of the pandemic.

Laurie, 67, shared the news of his infection today in the midst of a string of high-profile COVID-19 cases, including President Donald Trump, First Lady Melania Trump, and presidential staffers.

He cautioned Americans against the impulse to blame the White House.

“Unfortunately, the coronavirus has become very politicized,” he said in remarks to CT. “I wish we could all set aside our partisan ideas and pull together to do everything we can to defeat this virus and bring our nation back.”

After news of Trump’s diagnosis broke, multiple people who attended the president’s Supreme Court nomination ceremony at the White House over a week ago also tested positive. The infected attendees included former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, who sat in front of Laurie, and Notre Dame University president John Jenkins. Online, some began speculating that the gathering was a “super spreader event.”

“I don’t even know if I personally got the coronavirus at the White House,” he said. “I had tested negative before the event.”

A source familiar with the ceremony told CT the evangelical advisers who gathered to pray inside with the president earlier in the day on September 26—many of them sitting together, unmasked in the Rose Garden crowd—had actually all been tested prior to their participation.

Other than Laurie, no other evangelical leader in attendance has reported a positive test, and several who were there went on to lead in-person services over the weekend rather than quarantine.

A spokesman for Calvary Church told CT that Skip Heitzig, a New Mexico pastor at the event, tested negative prior to the White House gathering and twice since, most recently on Saturday.

Representatives for Franklin Graham and Liberty University acting president Jerry Prevo, who were both in attendance, told the Religion News Service they tested negative afterwards, as did Trump’s top spiritual adviser and pastor Paula White-Cain. Georgia pastor Jentezen Franklin shared on social media that he tested negative as well.

Courtesy of Greg Laurie

Courtesy of Greg LaurieAt both the Rose Garden ceremony and the prayer march, organized by Graham, Laurie was photographed not wearing a mask. He said he only took off his mask for pictures. One clip he posted last week does show him un-masking to chat with Johnnie Moore, a fellow evangelical adviser, at the march.

Laurie’s church complied with California’s restrictions on worship during the pandemic, only returning to outside gatherings with temperature checks, masks, and social distancing. He spoke up during the spring to challenge pastors who put their congregation at risk, saying, “I know you may see this as an act of great faith, but I think in many ways you’re testing the Lord more than you’re trusting the Lord.”

Laurie posted a video Monday on Twitter, sharing the news and explaining that his symptoms are mild at this point: fatigue, aches, fever, loss of taste, and boredom. He spoke with a mask resting on his leg.

“I have always believed COVID was a pandemic and have tried to encourage people to take it seriously. Clearly, the scientists believe that the virus is contagious enough that it merits a vaccine,” he told CT. “Clearly, if the president can get it, anyone can.”

Another high-profile evangelical leader also contracted COVID-19 recently: John Hagee. Hagee’s son Matt announced at Cornerstone Church on Sunday that the San Antonio preacher, age 80, had also contracted the virus after being “diligent throughout this entire COVID pandemic to monitor his health.”

Though John Hagee, who leads Christians United for Israel, attended a White House event on September 15, he was not depicted at the September 26 gatherings. The younger Hagee said his father’s doctors caught the infection early and asked the congregation for their prayers.

This post has been updated.