Years ago, my family lived in a small house outside of Glasgow, Scotland. I was completing postgraduate work, so most of my time was spent with my family or my books. But as occasion would allow, I also enjoyed hiking with friends in the nearby hills.

On one such outing, two neighbors took me to the Campsie Fells. One of my guides was a university professor; the other was a retired police officer. During our excursion, the retired officer reminisced on his years with the Scottish police force. One question that he posed has stuck with me.

“Why do American police all carry guns?” he asked. After my attempted answer, he offered his own perspective: “We would never consider arming ourselves when I was a police officer. To do so would undermine our role and would jeopardize the relationship we wanted to build with the public.”

I am not suggesting that American police should or should not carry sidearms. But in a moment when cries to reform (or abolish or “defund”) the police have reached a historic volume, this outsider’s perspective reminds us that the American policing paradigm is not the only possible model. Nor is our current system sacrosanct.

Christians should not hastily dismiss calls for change—even calls to “defund” and redesign policing from scratch. Our faith teaches that the kingdoms of this world are broken. We should not be surprised, therefore, if American policing needs transformation. But if Christians intend to contribute to this debate, they should first revisit the Bible’s lessons on policing—beginning in the Old Testament Law. (Read Esau McCaulley’s companion essay about New Testament perspectives on policing, also in CT’s September issue.)

God gave Israel his laws to teach them how to flourish as a community of love (Mark 12:28–34). Biblical laws are framed in the terms of an ancient society. They are not composed for direct implementation in this New Testament age. But we can still learn from their wisdom. That includes their wisdom on policing.

Strictly speaking, there was no police force in biblical Israel; but there were systems for community policing. Two institutions are particularly noteworthy. First, emergencies were handled with the hue and cry. Second, non-emergency crises were handled by a kinsman redeemer.

The Hue and Cry

The phrase hue and cry refers to a practice observed in many ancient societies, including Israel. Under this custom, a witness or victim of crime was expected to cry out, and all within earshot were obligated to assist. The entire community was a “police force reserve,” activated by the alarm.

One example is found in Deuteronomy’s law concerning rape (Deut. 22:23–27). Under this law, a victim was expected, if at all possible, to raise an alarm. Those who heard would rush to help. Without any professional police to call upon, the community itself enforced the law. The passage also addresses an acknowledged weakness of this custom: A victim might be accosted where no one could hear the cry. Despite this gap (the solution to which will be noted later), the hue and cry was Israel’s method for confronting crime as it was happening.

This practice might seem quaint and unsophisticated by modern standards. But it is also refreshingly authentic. The Law’s use of the hue and cry teaches us that public security is the duty of all members of the community. We might hire professionals to police for us. (And with the heightened dangers of modern weapons and technology, having trained police at some level seems very desirable!) But fundamentally, the responsibility to keep the peace lies with the whole community.

In fact, the professionalization of policing is a relatively recent innovation. The hue and cry remained the norm in most societies into Medieval years and until the modern age. London’s Metropolitan Police Act of 1829 is generally regarded as the birth of the modern police force.

In many respects, professionalized policing has been vital to the growth of cities since the Industrial Revolution. But policing systems have changed many times in different societies. We ought to stand ready to critique, overhaul, or even replace our own system as needed. The Old Testament hue and cry reminds us that we are all our “brother’s keeper[s]” (Gen. 4:9).

The Kinsman Redeemer

The hue and cry provided help the moment a crime took place. But another institution, the kinsman redeemer, provided help after the fact.

Every adult male in Israel might fulfill the role of a kinsman redeemer at one time or another. A kinsman redeemer was the nearest male relative to any person who needed help. When petitioned, this kinsman would investigate his relative’s trouble and take steps to restore peace on the sufferer’s behalf.

The Law teaches this office through the example of crimes of bloodshed. But the kinsman redeemer took interest in other matters, like theft, as well (Num. 5:8). In the example of bloodshed, the nearest kin of the deceased was assigned the role. As the kinsman redeemer (or “avenger of blood,” as Numbers 35:19 puts it), it was his duty to investigate the circumstances surrounding the death. If he identified a killer, he was further empowered to arrest and execute the guilty person. But he could only do so when there was sufficient evidence, especially in the form of witnesses (Num. 35:16–30). When guilt was in question, a trial was required before a jury of local residents (v. 24). If they handed down a guilty verdict, the murderer was turned over to the redeemer for execution (Deut. 19:12).

Through these processes, the kinsman redeemer served as the investigator, the arresting officer, the prosecutor at trial, and potentially the executioner. In fact, his role also encompassed resolving matters of economic distress, such as indebtedness (Lev. 25:25). The kinsman redeemer’s role, then, was much broader than what constitutes policing today.

That God’s Law gives this office the title of “redeemer” is no coincidence, since God calls himself Israel’s Redeemer (Ps. 78:35). By orchestrating the Exodus, he redeemed Israel from its slavery, poverty, and oppression, as well as from the diseases of Egypt (Deut. 7:15) and the sins and idols of that land. Scripture teaches that God redeems his people from all their troubles (Ps. 103:1–5), and the Exodus was the quintessential example of this redemption.

When God gave the title “redeemer” to Israel’s kinsmen, he charged them with delivering their relatives from injustice and oppression on a smaller scale. God desires this work of civic redemption to reflect his own divine redemption (Lev. 25:23–24, 47–55).

Today, we might devise different methods to redeem the impoverished and the victims of injustice. But the Law teaches that all such work is ultimately God’s work. Justice must be pursued in harmony with heaven’s redemptive purposes.

Protections Against Abuse

Through these institutions, biblical Law provided for peacekeeping in a society that lacked a police force. But naturally, putting policing into the hands of the public opened up many possibilities for abuse. Therefore, the Law also provided systems of oversight and appeal.

For example, in a society that depended on kinship for justice, the widow, the fatherless, and the foreign immigrant (“the foreigner residing among you,” in the words of Exodus 12:49) were often at risk. Biblical Law contained special provisions to guarantee the protection of those who usually lacked a kinsman redeemer.

Exodus 22:21–24 warns, “Do not mistreat or oppress a foreigner, for you were foreigners in Egypt. Do not take advantage of the widow or the fatherless. If you do and they cry out to me, I will certainly hear their cry. My anger will be aroused, and I will kill you with the sword; your wives will become widows and your children fatherless.”

In effect, this law made the entire community into proxy kinsmen redeemers for those without family. If the community as a whole failed to protect the vulnerable, God would make the men’s own wives into widows, and their own children would become fatherless. God thereby required his people to protect vulnerable members of the community as if they were protecting their own families. Indeed, with this warning, they were!

Cities of refuge (Num. 35:6–34; Deut. 19:1–13) added another hedge against abuse. The Law established a series of sanctuary cities, evenly spread throughout the kingdom. When a kinsman redeemer went rogue, a threatened individual could flee to the nearest city of refuge.

For example, a person might be wrongly accused of murder after an accidental death took place (Deut. 19:5; Num. 35:22–23). The kinsman redeemer, blinded by anger, might seek revenge, “even though [the man] is not deserving of death” (Deut. 19:6). In such a circumstance, the individual could flee to a city of refuge. The elders there would not determine guilt or innocence, but they would ensure a just trial.

Another interesting example appears in 2 Samuel 14:1–15. The case in this passage was actually a ruse invented by one of King David’s generals to make a point to the king. In it, a widow petitioned David’s court on behalf of her son. She said that a kinsman redeemer was going to execute her son for murder. Even though the case was staged, it illustrates another possibility for appeal.

The widow conceded that the charges were valid and that the redeemer had a legitimate claim. But she also had claims that the court was bound to consider: Executing her remaining son would remove her only source of support (Ex. 22:22–24; Num. 27:8–11). In this case, the king promised to intervene on the widow’s behalf. Even justified claims of a redeemer could be appealed in certain circumstances.

These protections illustrate some of the ways in which biblical Law guarded against the abuse of policing authority. They also remind us that no system of justice is perfect; even the system that God designed for Israel was liable to abuse! We should not be surprised to find that American systems contain loopholes and vulnerabilities that demand accountability or correction. Biblical Law trains us to be discerning in these matters, so that principles of justice—not just systems of justice—are upheld.

Israel’s Ultimate Law Enforcer

By these and other practices, God gave Israel institutions for law enforcement. But he did not abandon his own oversight. On the contrary, Israel sought just relations among themselves precisely because God would otherwise stir himself to act. One reason for human justice is to resolve matters quickly and avoid the need for heaven’s intervention.

If the community left injustice unresolved, God would visit his wrath not only upon the perpetrators but on the whole community for allowing it (Ex. 22:21–27; 2 Chron. 19:10). Second Samuel 21:1–14 provides an example that is relevant for today.

In the days of King David, a famine fell upon Israel. The king sought the Lord and learned that the famine was God’s judgment. The previous king, Saul, had undertaken a program of racial atrocities against the Gibeonites: “Saul in his zeal for Israel and Judah had tried to annihilate them” (v. 2). Israel failed to heed the cry of the Gibeonites living among them, but God heard it, and he visited his wrath on the land.

Upon discovering this unresolved injustice, David immediately summoned the Gibeonite leaders. He asked for their help to identify measures that would satisfy their grievances. David’s goal was to resolve their cries of injustice and to inspire their prayers “to bless the Lord’s inheritance” instead (v. 3). David and the Gibeonites came to a solution, and “God answered prayer in behalf of the land” (v. 14).

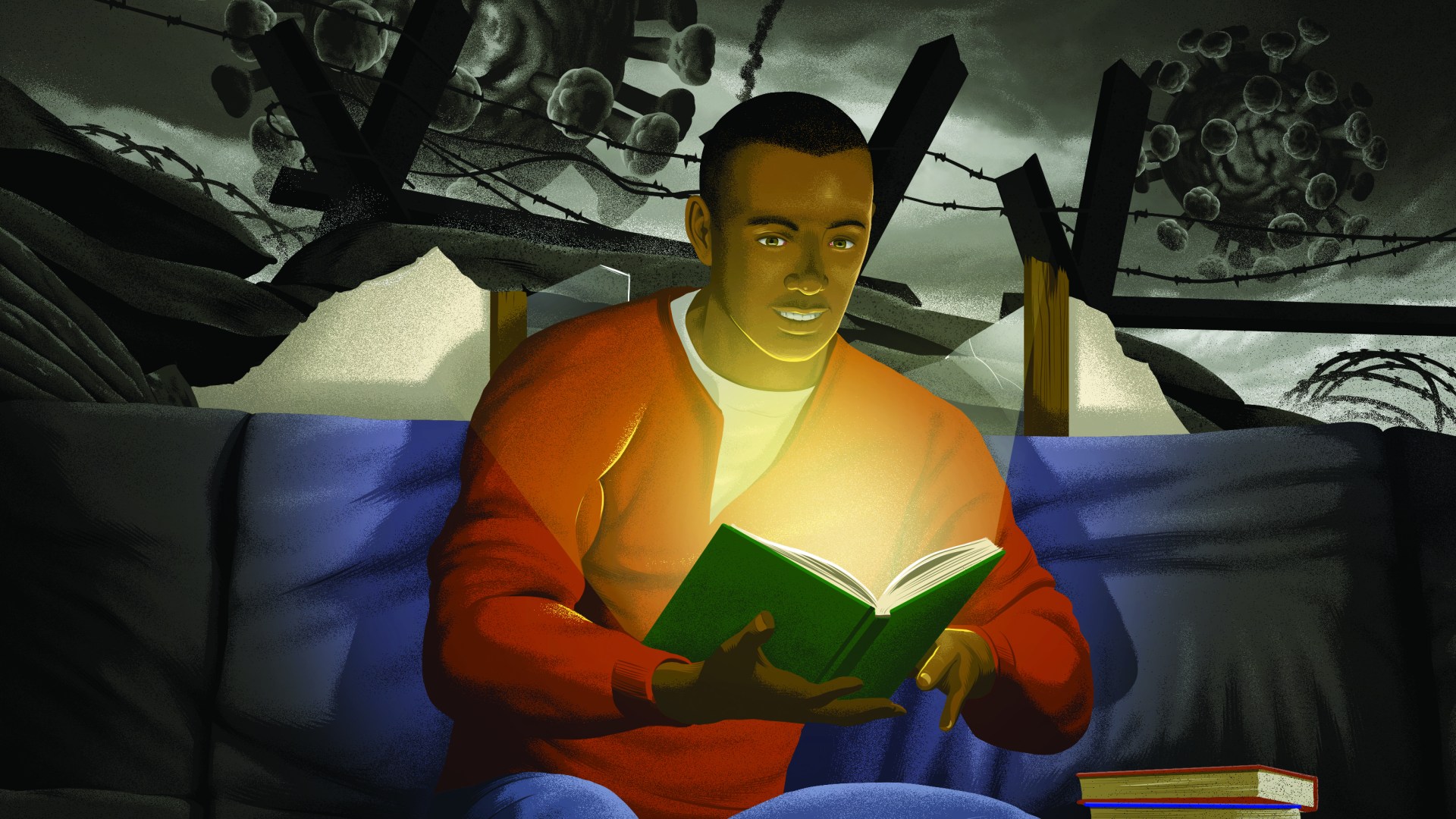

Today, the African American community is literally crying out in our streets. It is crying out against injustice in our nation’s policing systems. As Christians who fear God, we ought to sense the same urgency King David recognized, knowing that God hears the cries that humans ignore. We ought not dismiss these cries hastily but should listen and seek measures aimed at resolving them. Otherwise, heaven’s judgment will continue to mount against the nation.

Biblical Law shows us that there are different ways to implement law enforcement, as long as we uphold justice. Here is a vital principle to distill from all these considerations in the Law: The primary purpose of policing is to ensure that everyone receives justice before God—especially those least able to defend themselves.

This is a radical insight for our day. The biblical measure of policing is how well vulnerable, minority communities are protected. Americans commonly say that police maintain “law and order.” But this expression can overlook the biblical heart of policing. Biblical law enforcement is not about society’s “neatness” (its law and order) but about its justice.

The Old Testament frequently employs the language of justice and righteousness to describe the biblical aims of law (Gen. 18:19; Ps. 72:2). God’s purpose for law enforcement is to ensure justice, especially for those easily abused by the powerful, and righteousness, especially for those suffering under society’s inequities. Law and order, which tend to protect the status quo, is not sufficient. Justice and righteousness for those most disadvantaged by the status quo is the biblical purpose for policing.

America’s streets presently resound with the cries of our communities of color. The lessons of Old Testament Law urge us to open our ears and to undertake whatever renovations are necessary to ensure they receive justice. If we do not provide that justice, a higher court will answer their hue and cry.

Michael LeFebvre is pastor of Christ Church Reformed Presbyterian (Indianapolis) and a fellow with the Center for Pastor Theologians. He is the author of The Liturgy of Creation: Understanding Calendars in Old Testament Context.

Read Esau McCaulley’s companion piece here: