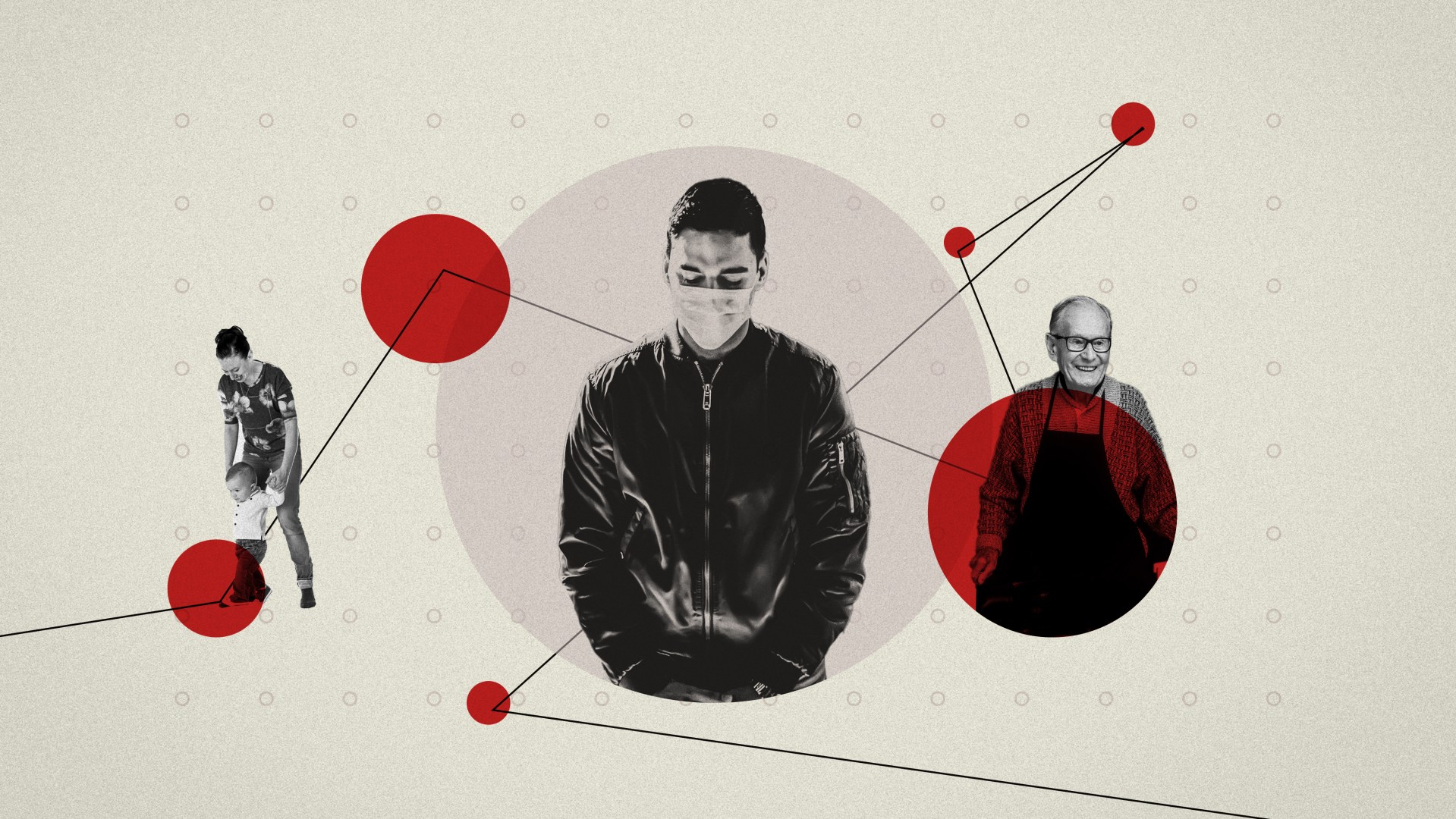

Two California churches were so eager to meet last weekend that when their services began, worshipers erupted in applause.

In Sun Valley, congregants filling Grace Community Church’s 3,500-seat sanctuary rose and cheered, some documenting the moment with their iPhones, when pastor John MacArthur opened the second week in a row of in-person services.

MacArthur—who has taken an outspoken stand against churches yielding to government regulations on worship gatherings—said this Sunday was “a very special day for a more abundant joy” since the congregation was together in person once again.

The Grace to You preacher received so much attention for his stance—from the elders’ viral post on the church’s website to a segment on Tucker Carlson’s Fox News program—that the church added an additional 1,000 chairs outdoors yesterday. Prior to the pandemic, attendance at the church’s three services averaged around 8,000 combined. On Sunday, most attendees were not wearing masks, social distancing, or avoiding contact, as MacArthur told Carlson, they “didn’t buy the narrative.”

The congregation sang “We Gather Together,” which MacArthur pointed out was written when Dutch Protestants met for church despite being forbidden by their king. MacArthur preached on Jesus’ role as divider and judge, saying that in recent months, “I’ve never heard so many people talking about death on such a superficial level. You’re talking about eternity, eternal hell or eternal heaven.”

An hour away in Riverside, California, worshippers at Harvest Christian Fellowship were greeted with cheeky pink and purple signs that said, “Smile with your eyes (and wear a mask)” and “Just leave room for your Bible—and another 5½ feet.” It was the third Sunday that Harvest met in a white tent half the size of a football field to comply with state orders restricting indoor worship. After the first week of meeting under the tent, pastor Greg Laurie said, “Our church loved it,” so Harvest added a second morning service.

Yesterday, volunteers scanned attendees’ foreheads with infrared thermometers to take their temperature before they entered the tent, where rows of six chairs were spaced about six feet apart. Masks were required—though, as in many places, not all wore them properly—and signs directed eager worshipers to wave at rather than touch each other.

Laurie, a longtime Calvary Chapel leader whose 15,000-member congregation joined the Southern Baptist Convention a few years ago, discussed in his sermon how people are prone to respond to the pandemic, the economy, and social unrest with anger and frustration. He referenced the debate over masks as one divisive example. He told the vocal crowd, “During this pandemic, God wants to use you. People are angry and scared, so you need to look for opportunities to share the love of Jesus wherever you go.”

Nicole Shanks / CT

Nicole Shanks / CTMacArthur and Laurie have each led their respective congregations for around 50 years, as they’ve grown into two of California’s biggest megachurches and their ministries gained national followings. While Grace and Harvest services have always looked very different—suits and organ music versus Hawaiian shirts and praise bands—the contrast is heightened as both find ways to worship in person during the coronavirus pandemic.

For many Christians, how churches meet during the pandemic isn’t merely a matter of style or structure. These decisions reflect their theology, with leaders explicitly calling out their priorities as a church and what they believe God would have them do in response to the current circumstances.

California reissued shutdown directives last month as the virus rebounded, ordering places of worship to “discontinue indoor singing and chanting activities and limit indoor attendance to 25 percent of building capacity or a maximum of 100 attendees, whichever is lower.” As happened in Nevada, some churches sued, saying the ban is unconstitutional.

Leaders at Grace opposed California’s stay-at-home order as it extended through the spring but agreed to “submit to the sovereign purposes of God” and stay online. But a few weeks ago, under the new regulations and after 21 weeks of canceling typical services, their response changed. MacArthur and Grace elders posted a 2,200-word “Biblical Case for the Church’s Duty to Remain Open.”

In a week, 21,000 people signed onto the statement, agreeing that “the honor that we rightly owe our earthly governors and magistrates (Rom. 13:7) does not include compliance when such officials attempt to subvert sound doctrine, corrupt biblical morality, exercise ecclesiastical authority, or supplant Christ as head of the church in any other way.”

Jonathan Leeman, a Southern Baptist who has written multiple books about faith and politics, raised concerns in a post for 9Marks that Grace’s statement doesn’t leave much room for faithful Christian leaders to come to other conclusions for their own churches. “Say, ‘We’re free to do this’ all you want,” Leeman said. “But take great care before you say, ‘And you have to do this too.’ Don’t sacrifice our spiritual freedom for your political freedom.”

MacArthur, who is 81 and celebrated 50 years of ministry last year, worries that Americans’ level of concern for their physical health during COVID-19 has become a detriment to their spiritual health—and the latter determines their eternal fate. Barna Group found that 1 in 3 practicing Christians stopped going to church in any form during the pandemic.

He has voiced his frustration with how few big churches are continuing to meet in spite of state regulations or coronavirus risks. “Large churches are shutting down until they say January,” he said in his update Friday. “I don’t have any way to understand that than they don’t know what a church is.”

Andy Stanley’s North Point Community Church, with 38,000 attendees in the Atlanta area, was the first major megachurch to delay Sunday worship gatherings in its building until 2021, though the church will still gather in smaller, in-person groups that can practice social distancing. J. D. Greear’s 12,000-member Summit Church in North Carolina has transitioned to a house church model for the remainder of the year. The proportion of pastors who don’t anticipate returning to normal in-person gatherings in 2020 jumped from 5 percent at the start of July to 12 percent last week, according to Barna.

During Sunday’s sermon, MacArthur suggested that churches that close are not true churches. “There has never been a time when the world didn’t need the message of the true church,” he said. “I have to say, ‘true church.’ I hate to think of that, but there’s so many false forms of the church. Let them shut down.”

The congregation laughed then cheered.

Some critics have questioned why Grace Church didn’t meet outside or adjust its indoor gatherings to meet health department guidelines rather than resort to a form of civil disobedience. Others brought up the risk of infection, since experts suggest church contexts, particularly with large crowds not practicing social distancing, are particularly susceptible to and responsible for several recent outbreaks.

“Given the flare-ups in some places, the churches that reopened have been following in many cases some rigid standards, but, at the same time, is that enough?” LifeWay Research executive director Scott McConnell told the Religion News Service (RNS), noting a recent drop in reopenings among California churches as cases spike. “Those questions I think will increasingly be asked.”

Phil Johnson, executive director of MacArthur’s Grace to You ministry, said in a tweet that moving gatherings outdoors to comply with state regulations wasn’t an option for Grace due to the size of the congregation and the California heat. He also said, “you don’t have to shut down the whole church” just because people might catch an illness.

Laurie, whose church borrowed a giant tent from evangelist Nick Vujicic for its recent worship setup, sees the outdoor setting as “our newest response to keeping people safe in California.”

“We don’t have to be in the sun, and we were easily able to sit in distanced seating groups and still feel like one big happy family,” Laurie told CT. Signs at the service acknowledged the change with an upbeat attitude: “Same Church. Fresh Message. New Experience.”

Nicole Shanks / CT

Nicole Shanks / CTLaurie, 67, has seen the bright side of the pandemic adjustments from the start. He celebrated “spiritual awakening” that took place online as more viewers accessed his sermon livestreams. One of those was President Donald Trump, and Harvest received an additional bump in viewers as Trump tweeted that he watched the Palm Sunday service. (Laurie belongs to the president’s evangelical advisory board.) To date, Harvest has received 80,000 online professions of faith and has sent Bibles to a quarter of the new believers that joined online.

Laurie shares concerns about closed churches with fellow evangelicals. He said he believes the local church cannot be replaced by online worship and he fears government overreach in regulating worship during the pandemic. However, he has also spoken out against downplaying the impact of the virus.

“I’ll be honest with you,” Laurie told the Los Angeles Times in April. “One of the things that kind of irritates me is the way some people are not really responding appropriately to the very real threat of the coronavirus. … Sometimes people are just ignoring it as though this has not been asked of us, and I think we want to be considerate of others.”

Fellow Southern California pastors have suggested that whether leaders see the coronavirus as a continued threat often determines the level of precautions they will take around meeting. The outlook has become increasingly politicized, with Trump supporters half as likely as detractors to say they are concerned about rates of infection and death from the virus.

In the spring, Laurie tried to convince pastors to shut down in-person services as the coronavirus spread. “I know you may see this as an act of great faith, but I think in many ways you’re testing the Lord more than you’re trusting the Lord,” he said in a Wall Street Journal article.

The Harvest pastor and revivalist also remains sensitive to how the coronavirus is turning into another issue stirring division and disagreement in the body of Christ. “When Christians love one another, they are a powerful witness. But when they are angry at one another, they are a poor witness,” he said in Sunday’s message. “What we need right now is less outrage and more outreach.”

In a LifeWay Research survey released last week, more than a quarter of pastors (27%) said maintaining unity amid conflicts over reopening was one of the biggest pressures they faced. They worried about the politicization of mask wearing and social distancing and how different members of their congregation regarded each other as a result.

MacArthur on Friday acknowledged there are church members who might not feel comfortable at indoor gatherings or might want to wear masks and social distance. “We love you just the same in doing whatever the things are you feel safer in doing,” MacArthur said, noting that masks and water would be provided in the new outdoor seating, where the livestream was projected outside a seminary building.

For the most part, Christians who fear that their right to worship freely is being taken away believe this is not the time for winsomeness. MacArthur stands by the church’s decision to reopen enough that he’s willing to risk the legal ramifications or pursue a legal battle, he said.

The Los Angeles County Public Health Department is looking into Grace Church for not complying with its restrictions on indoor worship and singing. “We are investigating reports that services were held indoors,” the department said in a statement to CT on Monday.

“We remind all houses of worship, consistent with other business sectors that also had to close indoor operations, that services must be delivered outdoors or virtually only at this time due to the current levels of COVID-19 spread. If the levels of spread were much better and control was sustained, we could return to reopening limited indoor operations for these and potentially reopen additional business sectors.