In the cover story of Christianity Today’s January/February issue, Paul Matzko makes a provocative argument that churches’ tax-exempt status comes at a cost, possibly even a detrimental cost, to both churches and the communities in which they are located. The argument is not necessarily new. Though the tax-exempt status for houses of worship has never been a leading political issue, it does make the news every now and then. It extends a “cultural privilege,” as Matzko calls it, that some cite as one more reason to resent religion. Matzko himself suggests the tax exemption leads to churches that live off “government largess” and accept the bribery of a tax benefit while forfeiting their religious freedom and their political voice.

I have a different view. Far from inhibiting religious freedom, tax exemption for houses of worship protects it. And in the highly unlikely event that churches lose their exempt status, the common good would suffer far more than it would benefit.

Safeguarding Religious Freedom

Contrary to Matzko’s portrayal of an across-the-board religious tax exemption as a vestige of European-style establishmentarianism, houses of worship are tax exempt to respect religious freedom and the separation of church and state. What offends American sensibilities about the European tradition is not tax-exemption, but the practice of taxing disfavored denominations, and using those funds to prop up the state and its favored religion.

Consider Isaac Backus, who Matzko invokes as an “evangelical dissenter” against government favors for religious groups. He was that, but hardly because he felt churches should pay taxes. As CT explained in a June article from 2018:

Far from operating from the center of power, Backus lived his adult life and ministry as part of a marginalized religious group in his native New England. Backus and his friends and relatives, including his elderly mother, were jailed (some of them many times) for refusing to pay taxes to support state-approved churches. Backus’s concern wasn’t the amount of the tax, but the state’s authority to collect it. “It’s not the pence but the power that alarms us,” he wrote. The liberty Backus fought to secure wasn’t abstract—he labored to end taxation for religion because he understood that the right to tax implied or presupposed the government’s authority to favor one religious group over the others. …

Paying the taxes, Backus believed, amounted to admitting that the state had a right to collect the taxes. So he fought for legislation to protect the conscience of Baptists. But he concluded that a free conscience demanded civil disobedience, and he proposed a nationwide display of it. Backus organized fellow Baptists to raise funds for posting bail, paying legal fees, recovering seized property, and compensating for lost wages.

Tax-exemption was not Backus’ problem then, and it makes little sense to enlist him—or his principled defense of religious freedom—in an argument to tax churches now.

It’s not just Backus who understood the effect taxation of houses of worship could have to harm some churches while potentially benefiting others. On social media, Matzko defended his essay by suggesting that Christians in financially comfortable churches should welcome religious taxation as it would help weed out churches that just could not cut it. This argument—support taxation so that religious rivals might be forced out of existence—should really inform how we consider the claim that it is tax-exemption which amounts to an undue government intrusion on religious life in America.

Of course, we should also recognize that houses of worship do create tax revenue. Many pay employees who pay income taxes and self-employment taxes. More generally, congregations and their employees obviously contribute to the economy through what they purchase.

And there are specific tax-related policies related to houses of worship that are worthy of real debate, including the clergy housing allowance and whether houses of worship should be required to file a 990—which other nonprofits typically have to file to qualify for tax exemption.

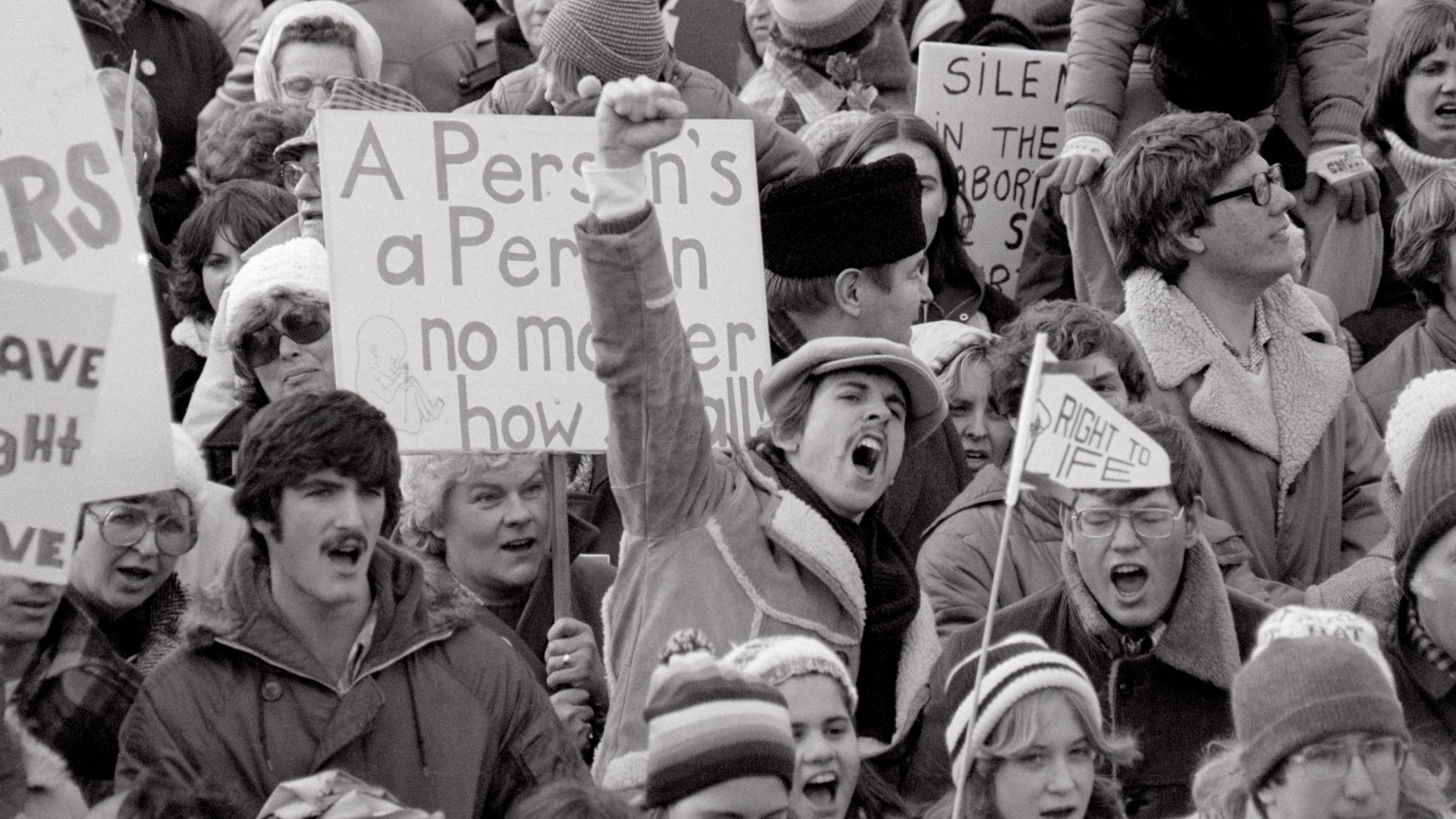

But in general, houses of worship should not be taxed, because doing so would open up new avenues for the government to exert control or influence on houses of worship that would weaken the separation of church and state. It would heighten the debates we already have about religious conscience and the idea of complicity. It is one thing to be a citizen, to pay taxes as a citizen, and to have your tax dollars go toward things that are in violation of your values—nuclear weapons or abortion, for instance. Imagine what our politics would look like if money intended for the things of God was now at the center of our most morally fraught political debates. “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s,” indeed.

If tax-exempt status is not some government favor that grants special privilege to houses of worship, perhaps it is a government bribe intended to harm and limit their political effectiveness for the benefit of those in power?

Some, including President Trump, argue that the Johnson Amendment, which applies to all nonprofits, allows tax-exemption to be used as a tool of political control. The Johnson Amendment is not a ban on political involvement. It does not bar people who work at nonprofits from political involvement, even in elections. As should be quite evident, the Johnson Amendment does not prevent pastors or churches from teaching on issues like poverty, abortion, the environment, or any other issue of public import. What the Johnson Amendment requires, with some exceptions and nuances that do not need to be described here, is that nonprofits not use their own resources to explicitly endorse a candidate, or lobby for a specific piece of legislation.

If the government intended to use tax-exempt status as a tool of political control, they’re doing a poor job of it. The last time the IRS revoked the tax-exempt status of a church was in 1995 after a church literally ran newspaper advertisements urging people to vote against Bill Clinton in the 1992 presidential election. The court suggested the church could set up a 501(c)(4) for that kind of political activity, just like any other nonprofit.

This argument that the Johnson Amendment silences Christians leads to an obvious question: Who could live through the last three years, the last three decades, and come away with the conclusion that the predominant problem facing the church’s political witness is that churches can’t go far enough in their political engagement? Now I believe and have argued that Christians could think about politics in healthier ways and engage differently, but that has nothing to do with the Johnson Amendment. How can a person watch Robert Jeffress and Rev. William Barber on cable news every week as they talk about 2020 and believe the real issue we must address is a government campaign to silence pastors? Outside of partisan or financial interest, exactly what could drive a person to suggest that a leading challenge to the Christian witness in America is that Sunday mornings in church aren’t more like Sunday mornings on Meet the Press?

Safeguarding the Common Good

Because churches facilitate a great deal of charitable work, taxing them wholesale could endanger a wide swath of the nonprofit sector. How could that be avoided? One option, as floated by Matzko, would be to tax the “worship service” portion of churches but allow them to move the vast majority of their community-facing staff, resources, and presumably even their property costs into separate 501(c)(3) organizations.

Ruminate on the world this would create for just a moment. Politically, whatever antagonism against religion there is now would not go away, but it would have new targets: the hundreds of thousands of newly created nonprofits that were created for the express purpose of limiting tax liability under the new regime. Also, it’s not just tax exemption that can be a political tool; the power to tax comes with a certain amount of coercive power as well. Once churches are taxed, it becomes a matter of public debate how much they are taxed. Different localities could tax houses of worship differently. Candidates will be able to campaign on the promise that they’ll not only lower middle-class taxes, they’ll lower your church’s taxes!

Churches, that would be under new financial pressures as they are now facing taxes avoided by culturally privileged nonprofits (and Amazon!), are now susceptible to political donors, campaigns, and others willing to pay churches to use their pulpit to advocate for particular candidates. Most, let’s hope, would resist. But it wouldn’t matter. Every reading of Scripture, every utterance, from every church pulpit would now be open to renewed and justified speculation that the pastor was responding not to the prompting of the Holy Spirit but the prompting of a donor. If pastors think the pressure they feel to speak out about politics is bad now, wait until they experience the mobilization campaigns to get them to put a Donald Trump or Bernie Sanders poster on the church doors.

Culturally, no one who currently thinks the church is useless would suddenly become pro-church, but our tax and legal systems would declare religious teaching as uniquely lacking public utility in a way that would result in additional taxation and social stigma. Remember, the entire nonprofit edifice would still exist. If you wanted to bring people together every week to learn about sea turtles (no offense to sea turtles intended), you’d be tax exempt. If you wanted to bring people together every week to learn about ultimate reality, the Creator God who made the sea turtles (acknowledgment of the worth and value of sea turtles definitely intended), you better pay up to Uncle Sam. You could be a hate group. Your organization could even be a nonprofit organized around the hatred of churches, and so long as it’s not a church, it could be tax exempt.

Ultimately, taxing houses of worship would not help churches with image problems or send the message that they are committed to the public good. Rather it would ratify the idea that they have nothing to do with the public good at all. It would weaken the best aspects of the wall between church and state, and strengthen the worst.

Religious tax exemptions are not to blame for the view that churches do not promote the common good. Revoking the tax exemption will not persuade the doubters, and government policy should not be used for the express purpose of helping churches change public perception. There are no easy answers to the real cultural challenge that too much of the public does feel negatively about churches, but there are more direct ways to go about addressing it. Churches can decide themselves to do more and invest more in their communities, and Christians can grow in their understanding about the purpose of the local church. If you believe that taxes and government contribute to the common good, you don’t have to support cutting taxes as a leading political priority.

Christians should support the tax exemption for houses of worship, however, because it is critical for religious freedom, and because houses of worship have at least as much claim to be oriented toward the public good as any other category of nonprofit. We do not need our churches to be electoral battlegrounds, and the government does not need a financial cut of what is meant for God, the edification of his people and the good of the communities in which they are located.

Michael Wear is chief strategist for the AND Campaign. He advises Christian organizations and leaders who engage in public issues. Previously, he led faith outreach for President Obama’s re-election campaign and served in the White House Office of Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships.

Speaking Out is Christianity Today’s guest opinion column and (unlike an editorial) does not necessarily represent the opinion of the magazine.