Complementarianism Examined

Complementarianism is a view of the relationships of men and women in the home, in the church, and in society. According to Wayne Grudem, the complementarian view is equality “in value and dignity” but “different roles in marriage as part of the created order.” And different roles means a hierarchy of leadership/headship and subjection/submission. Hierarchy then is at the heart of conservant Protestant complementarianism.

The primary role for the man is to provide, protect, and to lead while for the woman it is to respect her husband and serve as his helper. Women’s primary role then is assigned to the home.

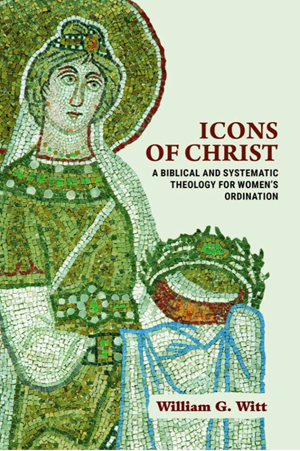

We are looking at William Witt’s new book, Icons of Christ. In a previous post we sketched his view that the traditional view was ontological inferiority, that both Roman Catholics and conservative Protestants shifted away from such a view to equality, and that the continuation of subordination was different for both groups. Catholics root difference in sacramentality of the priesthood while the complementarians make it a matter of authority.

In this post we turn to his 4th chapter, called “Hierarchy and Hermeneutics.” The chp is about complementarianism and he concentrates on Wayne Grudem. It is accurate to say Grudem is the primary spokesperson for this view, it is also accurate that not all hold his every view, and it is just as accurate that complementarians who don’t agree with his every view are more than hesitant to speak up for fear of damaging the cause.

A brief on which groups we are talking about here:

Although there are many Protestants who are opposed to women’s ordination – entire denominations (such as the Southern Baptists and the Missouri Synod Lutherans, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church), their related seminaries (Southern Baptist Seminary, Concordia Seminary, Westminster Seminary), and several parachurch organizations (Campus Crusade for Christ, Focus on the Family, Promise Keepers) – Wayne Grudem is the single individual who is most identified with the cause of opposition to women’s ordination among North American Evangelical Protestants. In 1991 Grudem and John Piper edited Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism, a series of essays that marked the beginning of the theology of “complementarianism,” and the formation of a group called “The Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.”

Since the founding of CBMW this group and its views have shaped other groups, like The Gospel Coalition, Crossway publishing, and influential leaders like Matt Chandler, Mark Driscoll, James Macdonald, D.A. Carson, and Douglas Moo. It’s a movement with a lot of heft. People in that movement or on its fringes have learned to stay in line.

Grudem is known for being specific about those he sees as straying (Wheaton, Denver Seminary, Asbury, Regent in Vancouver, IVP etc) and he’s clear on what can be done by women and what can’t be done.

Grudem provides a detailed list of positions that must be restricted to men: president of a denomination, senior pastor in a local church, preaching in the pulpit to the whole church, teaching Bible or theology in a seminary or Christian college, leading a home Bible study that includes both men and women. At the same time, Grudem suggests that both men and women can do the following: be director of Christian education, Sunday school superintendent, choir director, administrative assistant to senior pastor, or church secretary, teach a high school Sunday school class, write a book on Bible doctrines or a commentary on a book of the Bible, teach a women’s Sunday school class or Bible study group, teach Vacation Bible School, teach as a Bible professor at a secular(!) university, be an evangelistic missionary, perform a baptism, help serve the Lord’s Supper, sing in the choir, give a testimony at a church service.

Witt contends this is not so much role differentiation as it is role exclusion. Women are excluded from some, men aren’t.

A stunning observation, and this has recently been established by Kristin Kobes Du Mez (Jesus and John Wayne), is that this set of specifics looks like the era of Lassie and Ozzie and Harriet and Leave it to Beaver. Here are Witt’s words:

The above pattern of permissible church roles for women has a striking resemblance to the kinds of roles that women regularly would have played in American Protestant churches in the 1950s, the time during which Grudem grew up: church secretary, choir director, singing in the choir, teaching children. Even the one area where Grudem allows a woman to exercise a form of public ministry – as an evangelistic missionary – was an area where women were traditionally [that period of American history] allowed a certain freedom among American Protestants before the rise of the modern women’s movement. One wonders whether “complementarianism" does not represent so much a concern for biblical authority as a nostalgia for a kind of Evangelical Protestant era that no longer exists. [my emphasis]

Yes, this is my experience. I remember precisely these roles for women in the church in which I grew up. I remember we had two missionary sisters in our church: Grace and Kathryn Jepsen. Both of whom taught Bible and were sharp in theology. When they were on furlough they would testify in our church. My father sometimes observed that Grace was as good a Bible teacher as he’d ever heard, but she can’t preach – he was not pleased – “because she’s a woman.”

All of the 1950s came crashing down in the women’s movement, the ERA, etc, and before long these complementarians were affirming ontological equality. The tension was palpable.

So The Question:

If women are not inferior to men in terms of intelligence, emotional stability, or susceptibility to temptation, what is that essential difference that makes men capable of exercising leadership and authority, but not women?

For the complementarians this was about the Bible, and doing what the Bible says. For the Catholics it was about sacramentality.

Grudem again on the egalitarian vs. complementarian view.

While Grudem himself insists that the differences in interpretation amount to a clear choice between an acceptance of biblical authority (his own position) and a rejection of it (the egalitarian position, or what he insists on calling “evangelical feminism”), his own position involves just as much hermeneutical interpretation and application as that to which he is opposed. For example, Grudem interprets Paul’s statement that "the women should be silent in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak” (1 Cor. 14:34) to mean that women should not engage in public preaching or public teaching of men or exercise of leadership over men. But this goes beyond what Paul says. A literal reading of Paul’s words would be that women should be absolutely silent and never speak a word in a church setting.This seems to defy common sense, and to be in conflict with what Paul says elsewhere, so Grudem engages in a process of speculative hermeneutical interpretation; he does not subscribe to the literal meaning of what Paul actually wrote, but interprets this in light of what he thinks that Paul must have meant, and then arrives at suggestions at how this might be applied today. For example, Grudem allows women to sing in choirs, to give public testimonies in a church service, and to teach Sunday school classes to children, none of which Paul actually mentions, and all of which would be in violation of a literal reading that “women should be silent in the churches.”

It is a fact that many of us see Grudem guilty of special pleading in his attempt to extricate himself from the text. I’m reminded of Piper’s theory of “personal” vs. “impersonal” authority for Sunday morning preaching by a pastor.

Witt then turns to the critical texts for brief comments: Genesis 3:16 (subordination of some sort occurs only after the fall), to 1 Cor. 11, a text as notoriously difficult to interpret as any in the NT, to 1 Tim. 2:11-15, which has its own difficulties, and then to Ephesians 5 which “plainly” teaches mutual subordination.

That’s enough for today.

Jesus Creed is a part of CT's

Blog Forum. Support the work of CT.

Subscribe and get one year free.

The views of the blogger do not necessarily reflect those of Christianity Today.