Perennial favorite John 3:16 may have nothing to do with the war against Russia.

Isaiah 41:10 speaks more clearly to times of conflict—though it boasts a leading position in many other nations as well.

But missing from the top 10 list in Ukraine—and no other nation highlighted by YouVersion—is Jeremiah 29:11: “‘For I know the plans I have for you,’ declares the Lord, ‘plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.’”

Evangelical leaders shared their reflections on why millions of citizens in the Orthodox majority country may have found inspiration in the top 10 verses, not others, and suggest personal favorites that shed light on life in a war-torn nation:

Igor Bandura, vice president of the Baptist Union of Ukraine:

The results released by YouVersion are informative, inspiring, and challenging. My heart cries out in unison with all of them, as they reflect God’s love as the source of life within our deep search for meaning under the pressure of war. It is no wonder that John 3:16 ranks first, giving comfort against the power of darkness in the midst of loss, suffering, and simple exhaustion.

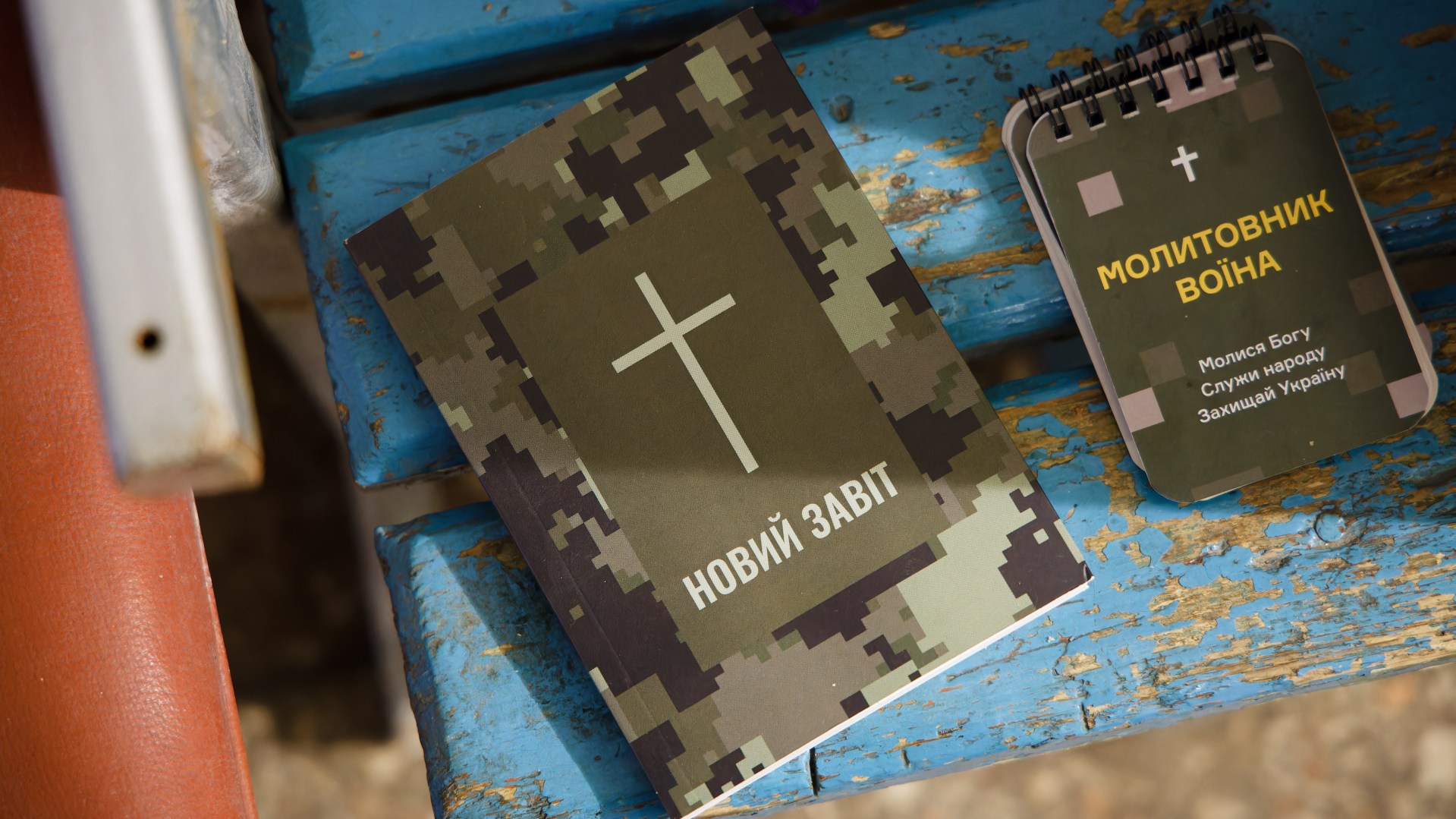

The Bible remains our most powerful source of encouragement, wisdom, and strength.

Perhaps Jeremiah 29:11 is left out because while God plans not to harm us, Russia does—and the imaginable near-term consequences keep Ukrainians from contemplating an unimaginable future. Certainly, this is a challenge for faith. But mine has been strengthened through a different unlisted inspiring verse in Zechariah 9:12: “Return to your fortress, you prisoners of hope; even now I announce that I will restore twice as much to you.”

There are two possible interpretations. First, that despite being prisoners of our overwhelming circumstances, there is still hope available to us. And second, that God’s hope has made us prisoners, and that we cannot live any other way. Both are true—and we await the “double” that God has promised.

Maxym Oliferovski, a Mennonite Brethren pastor and project leader for Multiply Ukraine, Zaporizhzhia:

That these 10 Bible verses have been shared the most in Ukraine does not surprise me at all. The first five focus on love, protection, and strength, communicating God’s care for us during the many hardships caused by the invasion. Most meaningful to me has been 1 Peter 5:7, “Cast all your anxiety on him because he cares for you,” because I tend to live in the future. But in the uncertainty of war, even short-term plans become impossible. God then reminds me I must rest in him, greatly decreasing my worry and stress.

The second five verses, taken together, strike me as a prayer for faith, holiness, and bravery. It is so easy to lose focus and get depressed. Certainly, we need healing, which comes through his Word. But we also realize that beyond the physical war in Ukraine there is a spiritual war waged against us—and these verses show us how to fight.

Guard your heart, says Proverbs. Seek first his righteousness, says Matthew. These verses help us care for our mental health, and then to discern the multiple opinions and outright lies that abound in both wars. Commitment to the truth of God’s kingdom is the plumb line to test our everyday actions.

If I were to add one verse to the list it would be the promise of Revelation 21:4: “He will wipe every tear from their eyes.” We pray for victory in Ukraine, and we anticipate the day all our mourning will come to an end.

Valentin Siniy, president of Tavriski Christian Institute, Kherson:

I see three themes in this list of verses. The first is God’s comforting presence in 1 Peter, Romans, Philippians, and especially Isaiah 40:10: “I will uphold you with my righteous right hand.”

Another set provides the remedy against the fear and weakness brought upon us by Russian aggression. Be strong and courageous, we read in Joshua. Timothy contrasts God’s love with timidity. And in Philippians we are reminded that God will give us the strength we need.

But the third group calls us to the church’s role in a broken world. We are to express God’s love (John 3:16), seek his kingdom (Matt. 6:33), and, in the process, guard our hearts (Prov. 4:23)—and by extension the hearts of those around us as well. Our perspective on the world has shifted, and as the church inquires about the theology of mission, it is no longer the dualism of church and state—it now crucially includes society as well.

Curiously absent are verses on evil, anger, and grief. One that I hear frequently quoted is Psalm 109:8–9: “May his days be few; may another take his place of leadership. May his children be fatherless and his wife a widow.” Applied to Judas in the New Testament, imprecatory passages like these have been an outlet for our emotions as we call for God’s justice.

Sergey Rakhuba, president of Mission Eurasia:

As Ukraine undergoes a brutal war imposed by Russia, we continue to fight for our freedom, independence, and even our very existence as a nation. A third of our population has been displaced with thousands of people killed, and especially for the innocent children caught in this chaos, this winter is a difficult season filled not with Christmas carols but the sad tones of resilience and struggle.

In this context, Jeremiah 29:11 may not be shared widely online where YouVersion can monitor its citation, but I can assure you that it is preached in churches and lived out in tangible service to millions of people who see it in action.

First given to the Jewish people during their time of exile and trial, I first received it 18 years ago when battling a severe illness and the possibility of life in a wheelchair. I was thick in a fog of despair, but its words dispelled my spiritual disorientation and filled me with divine certainty that God still had a plan for my life. The verse imprinted forever on my heart and has since been my beacon of hope. It is often through pain and deprivation that God shapes our faith.

But when tucking their children to bed in shelters with a night sky torn apart by the screech of ballistic missiles, telling a parent to believe that these are God's plans for their good seems almost incomprehensible. A theologian may be able to provide clear exegesis, but for the weary Ukrainian pastor—tirelessly caring for the endless needs of his war-torn community—it is not unreasonable to find doubt, difficulty of interpretation, or even the online neglect of this Scripture.

For me, the verse encourages us to believe in God’s providence, that there is a divine purpose even when the future of Ukraine seems uncertain. But it is also a powerful source of hope in overcoming adversity. Whether on the battlefield or in homes deprived by the chaos of war, it inspires resilience as we rely on God that better days are ahead, as determined by him.

These difficult days are not the end of our story.

Finally, the verse motivates us to long for and dream about an unknown future. God has plans for our lives, but we have a role in realizing them. It spurs on our efforts toward victory, but also to prepare for the healing, restoration, and recovery necessary after the war ends. Jeremiah envisions our prospering, and we are praying—and believing—that it will come soon.