Jack Sara sees buses of American Christians pass by his house as they tour around his homeland. He sees them stop, get out for a few minutes to take photos, and then get back on their buses and leave.

He wonders why they never come talk to him.

“The land of Christ is not just a museum,” said Sara, an evangelical pastor and the president of Bethlehem Bible College. “There is still a church they could meet and pray and fellowship with and get encouraged from.”

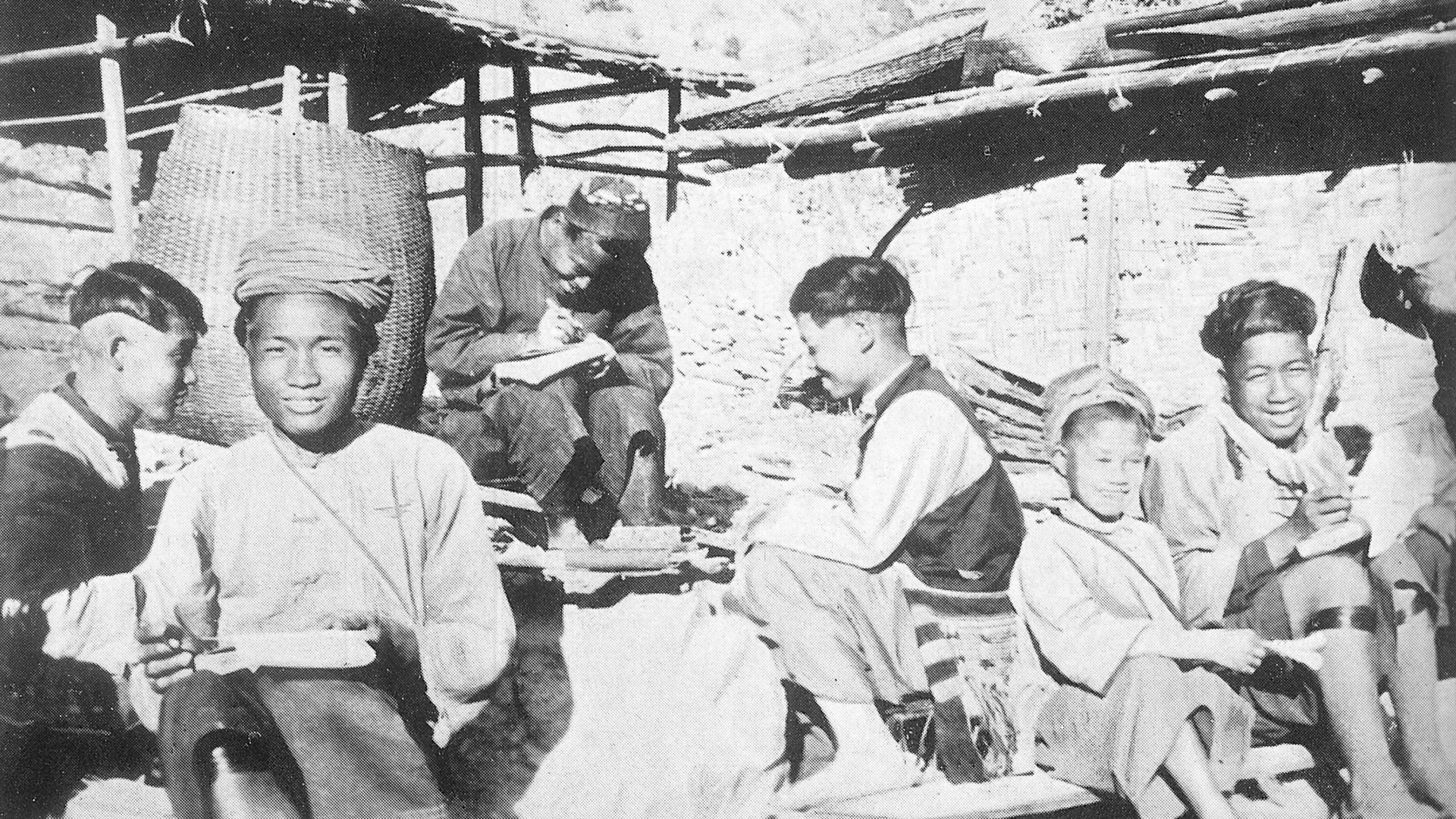

As many as 400,000 Americans visit religious sites in Israel each year. They go to walk where Jesus walked and see the land of the Bible: from the river Jordan to the Sea of Galilee to the traditional site of the Nativity, with stops at Mount Carmel, King David’s tomb, and the Mount of Olives, where Christ is said to have ascended. Yet few of these religious pilgrims connect with modern-day Christians in the Holy Land.

About 180,000 Christians live in Israel—just under 2 percent of the population. Three out of four of them are Arab. They include Byzantine, Roman, and Maronite Catholics; Eastern Orthodox; Coptic Orthodox; Armenian Christians; and a small number of Protestants like Sara.

Sara is a Palestinian who grew up in a nominal Christian home in Jerusalem’s Old City. He made a personal profession of faith and committed his life to Christ at Jerusalem Alliance Church in the early 1990s. Now—as president of the school he attended to grow deeper in his Christian faith—he hopes to connect more Christians from around the globe with the vibrant evangelical churches in Israel.

The Bible college is offering online classes to allow people to “Discover Jerusalem,” “Discover Bethlehem,” and “Discover Galilee.” The school also trains local Christians as tour guides and is working with an American ministry to facilitate different kinds of trips to the Holy Land.

Others also want to broaden people’s experiences in Israel. The Christian HolyLand Foundation is an Independent Christian Church–affiliated nonprofit ministry that supports church leaders in Israel and helps fund church and community projects. They are also organizing trips.

The Christian HolyLand Foundation wants to invite believers to think a little differently about the idea of “walking where Jesus walked,” said executive director Matt Nance. As a Palestinian Christian once pointed out to him, Jesus promised to be with those who gather in his name. He didn’t care about the dead stones at his feet. But he cared a lot about those whom one of his disciples would later call “living stones” (1 Pet. 2:5).

People are “totally missing where Jesus is walking today,” Nance recalled the Arab Christian telling him. “He’s not walking with dead stones. He’s walking among the people, and he’s experiencing our trials and our pain and our opportunities to participate in the mission of the kingdom.”

Nance, who is based in Knoxville, Tennessee, personally knows how powerful a trip to the Holy Land can be. When he was a university student, he studied for a year in Germany and during a break went to Israel and Jordan—backpacking, hitchhiking, sightseeing, eating a lot of street-food falafel, and absorbing as much about life and the culture as he could.

“I fell in love with that part of the world,” Nance told CT, “and decided I wanted to go live there if I could.”

In 2012, he moved to Jordan with his wife, Susan, and they made their home there for the next eight years. They immersed themselves in a local Christian community, and Nance worked under a local church.

That time in Jordan gave him another perspective on Holy Land tours, which often include extension packages that take Christians to Jordan and Egypt. Nance, like Sara, saw all these buses of believers that never stopped to connect with a local congregation. He felt kind of sorry for them.

“They just are not experiencing what life is like in this place today,” Nance said. “If you are only on your tour bus, tourist restaurants, and tourist hotels, you are missing a beautiful culture and you’re also missing getting to learn about the challenges and trials of what it means to live in this part of the world.”

Moneymaking Holy Land tours, of course, are constrained by the need to turn a profit. And they cater to consumers, responding to demand, not telling tourists what they should want to do on their trips to Israel. Nance wondered if a nonprofit that emphasized the spiritual value of connecting with Christians could draw believers to a different kind of experience.

Now back in the US, he is working with the Christian HolyLand Foundation, arranging trips that place a high value on these Christian connections.

As travel has opened up after the pandemic, the Christian HolyLand Foundation is organizing trips for churches that will allow them to worship with fellow believers in Israel. They will share a meal and perhaps even help with an olive harvest.

Ken Nelson, a retired TV news anchor in Indianapolis who went to Israel with the Christian HolyLand Foundation before COVID-19, said participating in an olive harvest was an especially memorable part of the trip. He beat the branches of the trees with a stick, as he was taught, to knock down ripe olives.

“It wasn’t just walking in the footsteps of Christ,” he said. “We met Arab Christians. Real, real people who have dedicated their lives, right here in the Holy Land, to Jesus Christ. We attended a local church service with their local pastors. We clapped our hands with them. We sang with them. … And you know what was there in the room with us? The Spirit of Christ.”

Each trip includes about 10 to 15 people, typically all from one congregation. The groups see some of the famous religious sites, as they would with other tour packages. They are led around by Christian tour guides—including those trained at Bethlehem Bible College—and interact with historical, theological, and archaeological experts, as well as local Christians.

Dave Mullins, pastor of Colonial Heights Christian Church in Kingsport, Tennessee, went on one trip and came back valuing the personal connections.

“Seeing their hearts for the kingdom has been really impactful,” he said. “All of the people I have interacted with have just been extremely warm, loving people.”

The experience also added to the complexity of his understanding of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He doesn’t think he has an answer to the ongoing crisis, but the trip made him pause and think, “Oh, wait a minute, these are my brothers and sisters in Christ who go through an awful lot in a land where they were born,” Mullins said.

He especially loved hearing about the ways Christians have helped facilitate reconciliation between Arabs and Jews. He’s hoping to bring a group from his church to the Holy Land next year.

Sara said he loves how many American Christians are praying for peace in Jerusalem, his city. But when he sees those buses come and go, he worries they are not praying for all the residents.

“You see them sympathizing with a certain group of people against another—taking a stand on the Israeli or Jewish side and opposed to the Palestinians,” he said.

If he can connect them to the lived experience of Christians in Jerusalem and the rest of Israel, they will meet Palestinians who are not enemies of peace but in fact love Jesus and have preached the good news of the Prince of Peace for many years.

“When you talk about Palestinian Christians, you’re talking about Christians who have been here for 2,000 years,” Sara said. “Christianity never left this country.”

Adam MacInnis is a reporter in Canada.