Church can be so disappointing. We want it to be healthy and vibrant, growing and missional, faithful and generous, but we often see more problems than triumphs, more fear than courage, and more weakness than strength in our local congregations. We are not always an attractive lot.

When we look outside the walls of our church, we see so many needs in our communities and across the globe: We want to care for the poor, proclaim the gospel, fight injustice, support struggling families—the list is endless. Our imagination is excited by what the church could accomplish, but then we often feel let down at how meager our work actually is. Are we destined to be perpetually disappointed by our churches?

Every church has limitations and challenges: Physical location, finances, narrow networks, and history shape each and every church. The long COVID-19 pandemic has increased the difficulties for many congregations, resulting in less church involvement and more mental health challenges, less relational connection and more political polarization.

If we are honest, it can make us feel hopeless. But what if, instead of looking at a church’s limits as mere hindrances, we begin to see them as signs of God’s work and promise? What if recognizing our limitations could nurture love, real community, and healthy mission? I would sign up for that. Three principles can help us avoid romanticism, liberate us to see the larger work of God, and ground us in God’s promises.

Reality vs. romanticism

Recognizing our church’s limits anchors us in the reality around us and prevents romantic illusions. Years ago, someone told me the story of a man who dated lots of women but kept breaking up with them. One woman was brilliant but couldn’t relax. Another was beautiful but had an annoying sense of humor. Yet another had an amazing career but didn’t share his intellectual interests. On and on it went. This man had a mental picture of the perfect woman, but she was a superhuman, not a real woman. What was the result of his thinking? He walked a path of loneliness and disappointment rather than finding real love with a real person.

Similarly, we often create an impossible image of church. Some churches have amazing music or impressive programs, and we want that for our church. Other churches tutor neighborhood kids, support homeless shelters, or find jobs for the unemployed, and we want that too. We hear of gifted preachers, pastors who know how to be fully present with the sick and elderly, and congregations that are richly diverse, while our own congregation is missing some or all of that. Every local church has the concrete particularity of these circumstances rather than those, and consequently does this but not that—and, of course, we often focus on the that and feel perpetually disappointed.

In the 1930s, young German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer was preparing pastors for ministry. They trained while sharing life together, and in the process, he showed them how social structures affect the life of the church. For example, a charismatic figure might stir people to action, but misuse of that attractiveness can destroy healthy communal life.

Bonhoeffer emphasized that little was more deadly to a community of faith than a romanticized view of life together. Unrealistic ideas easily disconnect us from our actual communities. “Those who love their dream of a Christian community more than the Christian community itself become destroyers of that Christian community even though their personal intentions may be ever so honest, earnest, and sacrificial,” Bonhoeffer observes in Life Together.

One of the most healing and powerful actions pastors can undertake for their congregations is to appreciate more fully the people God has gathered there. Since God is the one who lays the foundation and unites his body in Christ, Bonhoeffer emphasizes, “we enter into that life together with other Christians, not as those who make demands, but as those who thankfully receive.” For some, constructing impressive plans and visions is much easier than Paul’s call to widen our hearts to the exasperating people around us—but widen our hearts we must (2 Cor. 6:11, 13). God sends his grace for all the people who show up, and he teaches us to listen with interest to one another’s stories, to uphold one another in our heartaches, and to discover each other’s gifts and senses of calling.

These people, gathered here and now by God, come not in power or perfection, but in their need to worship Christ. This community is where you can move beyond hypothetical models of church toward a life of giving and receiving profound grace, forgiveness, and love. We are a strange and awkward group of people who don’t always blend naturally, but that very strangeness and awkwardness is a gift from God, and overlooking it injures us and our people. Our limits and our togetherness alike are part of God’s call to serve these people in this place, and are an indispensable part of his enabling us to do so.

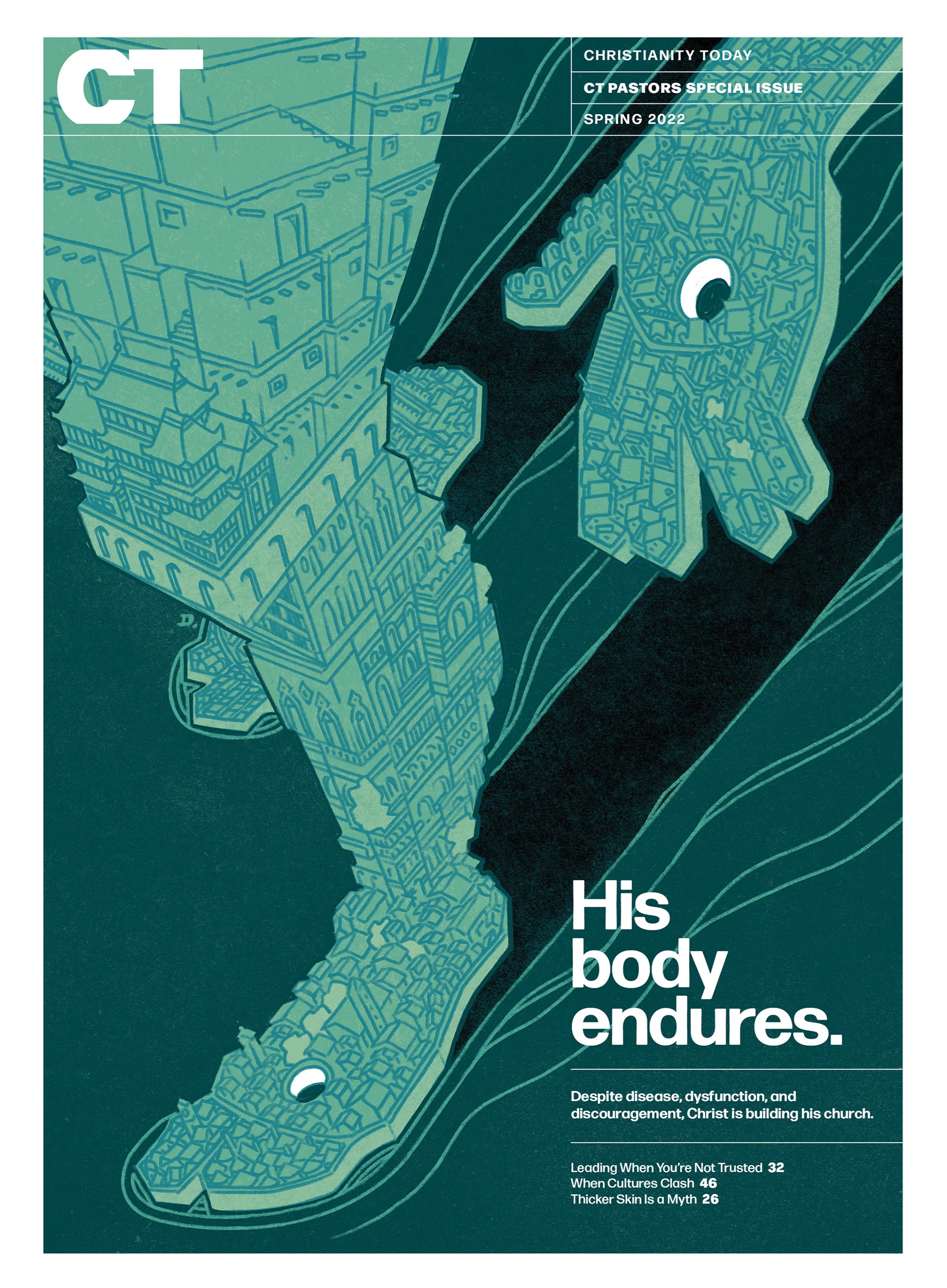

Illustration by Michael Marsicano

Illustration by Michael Marsicano

Uniquely equipped

Recognizing our church’s limits liberates us to focus on the work God equipped it to do while also valuing the larger kingdom work God is doing beyond our church. We have all seen children who, having received presents for Christmas, then notice a toy that another kid got and decide that toy is all they want. Similarly, we can all imagine how great life would be if we had the talents or resources of other people or churches. This applies to us as individuals and as groups. And when things are especially challenging for church leaders, it can be hard to even see the good that has been given, because we feel overwhelmed by the hardships and disappointments. Maybe we need encouragement to look again with grace.

As director of innovation at The Chalmers Center, my wife, Tabitha, works with churches and Christian nonprofits to help them serve their communities and especially to serve the materially poor. One of the principles she teaches is that rather than starting a ministry project by looking at what people need, we should often begin by looking at the gifts a community or person brings to the situation. When a ministry is driven by what a benefactor believes is needed rather than by a candid awareness of the actual assets they bring, people often end up getting hurt rather than helped.

All people—whether rich or poor, educated or not, big churches or small ones—all of them have gifts. The goal is to figure out what in particular God has given and how he has equipped this specific set of people, and then to nurture and employ those gifts for service in God’s kingdom.

For example, one church Tabitha worked with wanted to end child hunger in their city—a genuine, God-honoring desire—but attentive assessment showed that the congregation didn’t yet have the skills or knowledge required for such a ministry. This might sound disappointing, but for this church it was not. The assessment ended up liberating them to eventually pursue work better suited to their gifts and abilities: an effective day care ministry. It also freed people in the congregation to look outside the church’s own ministry structure for ways to fight child hunger. Some of them volunteered to work with other nonprofit organizations in their area that were already addressing this need.

All churches can bathe their members in prayer and send them out to work with groups and ministries that are equipped in ways that a particular local church may not be. Loving the church within its limits thus spreads that love beyond its walls. What about your local church? Before you despair, try seeing its assets as well as its constraints. Learn to flourish within the space God has given before trying to create new space somewhere else.

God knows all the needs in his church and world. And he knows that no individual, no local congregation can meet them all. God is not panicked or disappointed by this fact. He created each of us to depend upon him, others, and the earth. Only when we see our place within the much larger work of God can we move from disappointment with our local churches into joy and gratitude for the contributions we get to make.

Ignoring our church’s limits can lead to trying to develop ministries that fit neither genuine needs nor our abilities, and we miss out on what God is doing. Loving our church within its limits, acknowledging both its assets and weaknesses, allows its people to serve together without feeling disappointed that they can’t be everything to everyone.

It is God’s church

Recognizing our church’s limits reminds us that God takes responsibility for his people. Especially for those of us in various forms of church leadership, it is easy to feel the weight of the congregation resting upon our shoulders. Although we claim God loves his church, our lives often demonstrate that we feel like we, rather than God, are responsible for its survival. This false belief can emerge for many reasons, such as seasons when our earnest prayers endlessly appear to go unanswered, or when we see all the work that must be done and no one else steps up to do it. We keep doing more and more, slowly being crushed by the increasing weight.

In our discouragement, we may wonder in silence if God is really just distant and unconcerned, showing up only occasionally for big events or emergencies, as if he has given us the keys to the car and then disappeared. Our instructions? Don’t crash, keep going. At first we love the exhilaration of driving, but the cost of repairs and fuel soon overwhelm us. We look around and don’t see God, so we keep trying to fix the car ourselves, hoping that he will eventually come back to claim it and not yell at us too much.

Yet, ultimately, we know this to be true: The church is what God does, not what we do. Yes, God gives us gifts and energy to employ with freedom and vigor. God has called us to serve, and what we do matters. But as Bonhoeffer points out, that activity requires a deeper basis: “Christian community is not an ideal we have to realize, but rather a reality created by God in Christ in which we may participate.”

Bonhoeffer here rejected the temptation we often experience: imagining we alone are responsible for creating, growing, and keeping the church. The kingdom of God is a gift (Luke 12:32). The church, a gathering of God’s people who worship King Jesus, is God’s gift that we participate in, and not a movement we could start or sustain by our own powers.

Unlike CrossFit or garden clubs or any other organization designed to attract similar personality types, the church collects people who often do not naturally fit together. Sociologically, this looks like a massive disadvantage, but theologically it is a beautiful gift. God gathers us with all of our differences, united only by the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, into the fellowship of the Spirit and the Father’s love. God calls, cares for, and sustains his people.

What binds the church together is not believers’ goodwill or shared vision, but the Spirit of Christ. We do not generate the church; rather, we are liberated to participate in it with joy. Still we tend to forget: This is Christ’s church. As much as we love God’s people, he loves them more. He loves us more. He is more committed to the life and health of his church than we could ever be. Only when we drink deeply of that truth can our life together be driven by joy and hope rather than by frustration or manipulation.

Our strength, determination, and vision do not bind our church together—that is God’s work. God’s Spirit grows his fruit among his people—a fruit given to be enjoyed, especially by those starving for love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, goodness, and truth. Given the Spirit-led nature of the church, we can acknowledge when God closes doors or reminds us that we can only do so much, and that is okay. Jesus promises to meet us in and through his imperfect people.

Unlimited love

Loving our local church within its limits requires that we resist the temptation to idealize community, but instead embrace the people God has brought to us. We love Jesus in and through fellow believers rather than in spite of them. And this allows us to see our own specific congregation as a small part of God’s much larger universal work. Thus, we’re freed to view other churches and Christian groups not as threats or competitors, but as colaborers with whom we can rejoice.

God loves his church and promises to love the world through an unimpressive gathering of sinners who bow before the risen King. Our confidence is not in our faithfulness but in his. God knows our limits better than we do, so by loving others well, limits and all, we participate in God’s work without being crushed by it. May God help us to love the real, local church that we are part of, because it and we belong to him.

Kelly M. Kapic is a professor of theological studies at Covenant College and serves as an elder at Lookout Mountain Presbyterian Church in Georgia. He’s the author of several books, including You’re Only Human: How Your Limits Reflect God’s Design and Why That’s Good News.

This article is part of our spring CT Pastors issue exploring church health. You can find the full issue here.