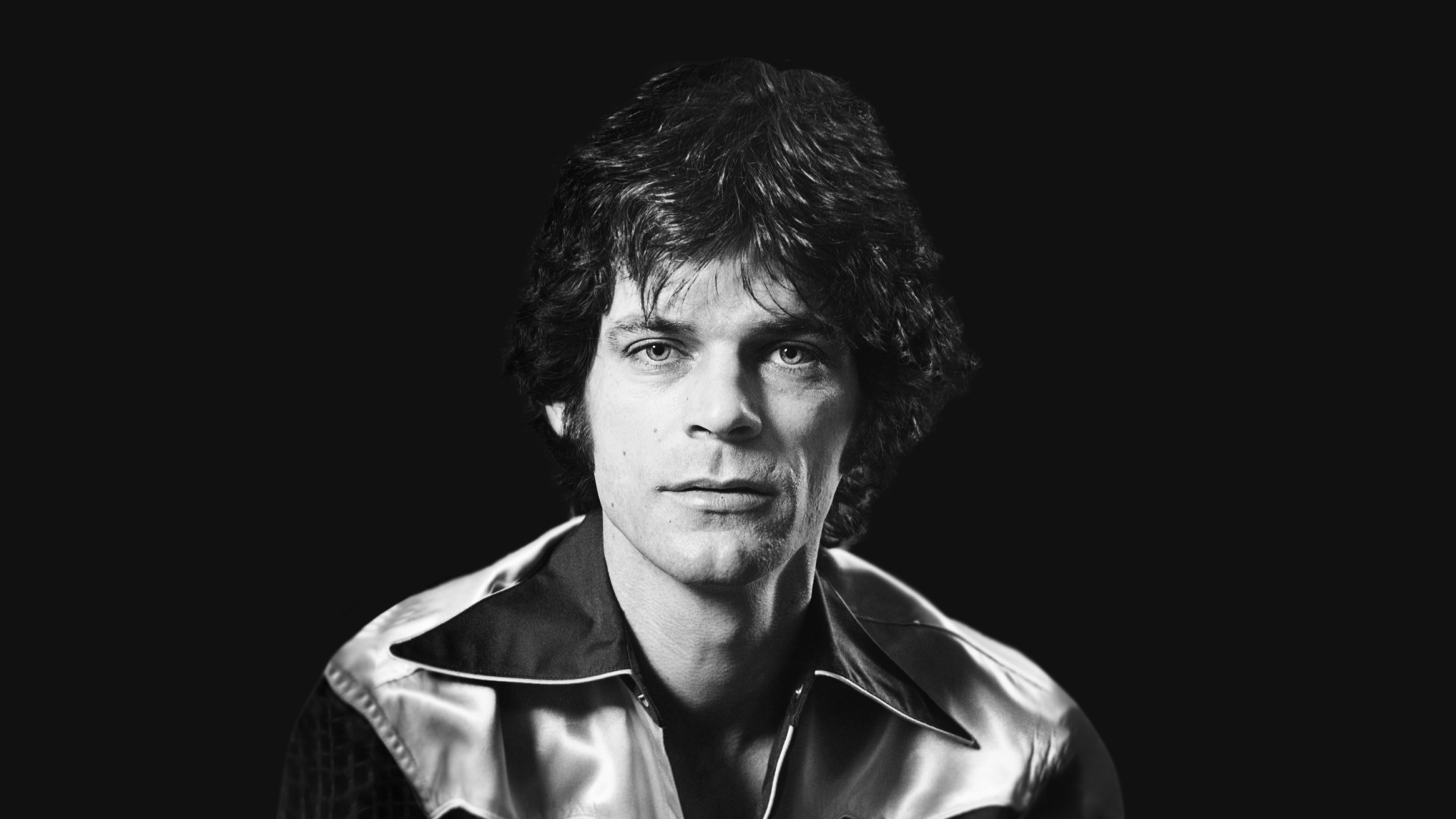

Christian celebrity didn’t sit well with B. J. Thomas. The famous singer of “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head” and “(Hey Won’t You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song,” personally loved Jesus. It was Christ’s followers that were the problem.

Thomas, who died May 29 at age 78, had a spiritual awakening in 1976. After his born-again experience, the pop and country singer with 15 singles in the Top 40 charts got off drugs and reunited with his wife, Gloria. He put out a massively successful album of Christian music. And he was confronted by an evangelical culture eager for stars but also instantly, angrily critical of them.

Thomas was hailed as a new evangelical icon and then heckled, booed, and berated by born-again fans who didn’t think he was performing his Christianity right. Other celebrities who have wanted to express their faith in pop music but struggled with the demands of believing fans—including Bob Dylan, Amy Grant, and Justin Bieber—would go through similar experiences in subsequent decades.

“I think it’s a really sad commentary when people who want to refer to themselves as quote-Christians-unquote would want to come out and hear someone just to boo them,” Thomas said in a 2019 interview. “That to me was always tough to deal with, and I just stopped making 100 percent gospel records.”

Thomas’s most public clash came in 1982, after he won his fifth gospel Grammy. He sang a string of his secular hits to an Oklahoma audience of more than 1,800, and a woman started shouting at him to talk about Jesus. He told her he wished Jesus would make her be quiet and then said, “I’m not going to put up with this” and walked off stage. Someone shouted, “You’re losing your witness, B. J.,” and there were scattered boos.

The singer returned to the stage and continued the show, but not before critiquing the fans.

“You people love to get together with your gospel singers and talk about how you lead all the pop singers to the Lord,” he said. “But when you get them in front of you, you can't love them, can you? I've got Jesus, but you can't love me.”

In CCM, Thomas complained that Christians “can’t seem to hear somebody sing. It’s always got to be some kind of Christian cliché or Bible song, or they feel it’s their right before God to reject and judge and scoff.”

Thomas continued to produce gospel records and Christian-themed music for the rest of his career, but he also recorded country and pop hits, including “Whatever Happened to Old Fashioned Love,” “New Looks from an Old Lover,” “Two Car Garage,” and “As Long as We Got Each Other,” the theme song for the sitcom Growing Pains. His shows were primarily secular, with a few religious songs mixed in.

He had, nevertheless, many committed Christian fans who mourned his passing over the Memorial Day weekend.

Thomas was born on August 7, 1942, in Hugo, Oklahoma. His parents, Vernon and Geneva Thomas, named him Billy Joe. He was raised in Houston, where his childhood was dominated by baseball, music, and his father’s alcoholism.

Thomas became the lead singer for a local band called The Triumphs at 15 and started drinking and doing drugs at the same time. The Triumphs had a hit in 1966 with Thomas’s cover of the Hank Williams’ song, “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.”

As a solo artist, Thomas cracked the top 10 charts with a love song in 1968, another love song in 1970, and the surprise hit “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” which appeared during a musical bike-riding interlude in the genre-defying Western Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford. The song won Thomas an Academy Award and spent four weeks in 1970 as the No. 1 song in America.

He had another No. 1 hit in 1975, with the self-aware and self-commenting broken-heart country song, “(Hey Won’t You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song.”

Success did not make him happy. In fact, it almost killed him.

As he later recounted in his memoir, cowritten with evangelical author Jerry B. Jenkins, he started doing more and more drugs until he was spending thousands of dollars every day on cocaine, which he supplemented with amphetamines and attempted to balance with Valium and marijuana. His personal relationships became rocky and his public performances irregular. Increasingly, he failed to even show up for concerts.

He overdosed in 1975, taking 80 pills at once. He was surprised when he woke up.

“I remember asking the nurse why I was still alive,” Thomas said. “She responded ‘God must want you to accomplish more here in this world.’”

When he got home on January 27, 1976, his wife, Gloria, told him she had accepted Jesus as her Lord and Savior and introduced him to an evangelical rodeo worker who explained to Thomas how he too could be saved. The man invited Thomas to pray with him, and Thomas poured out his heart to God.

“I began a 20-minute prayer that was the most sincere thing I had ever done in my life,” he later wrote. “I got straight with the Lord everything I could think of, and the bridge between 10 years of hell and a right relationship with God was just 20 minutes.”

According to historian David W. Stowe, Thomas’s conversion inaugurated the “Year of the Evangelical” and launched the phenomenon of “Jesus Rock” with his 1976 album Home Where I Belong, released by Myrrh. It was a No. 1 gospel album, won a Dove Award, won a Grammy, and earned Thomas a $1 million contract with MCA Records.

By the early 1980s, the Christian music circuit could boast a robust list of pop celebrities who confessed Christ, including Dylan, Donna Summer, Little Richard, Al Green, Arlo Guthrie, Noel Paul Stookey, Maria Muldaur, and Bonnie Bramlett. But if Thomas was the first on the scene, he was also the first to grow dissatisfied with the demands of Christian audiences.

“I’m not a Christian entertainer. I’m an entertainer who’s Christian,” he told a newspaper reporter in Wisconsin in 1982. “There is a large section of people who think a Christian singer has to sing Christian songs all the time. … This fall I’m working on getting my pop audiences back.”

In later years, he continued to include religious music in his performances, but he didn’t speak as much about Jesus.

“I might have been presented as a very religious entity in those days,” he told one interviewer, “but I'm not a religious person as we speak. And, I'm not sure that any one religion can serve all humanity.”

Thomas is survived by his wife, Gloria, and their three daughters, Paige Thomas, Nora Cloud, and Erin Moore.