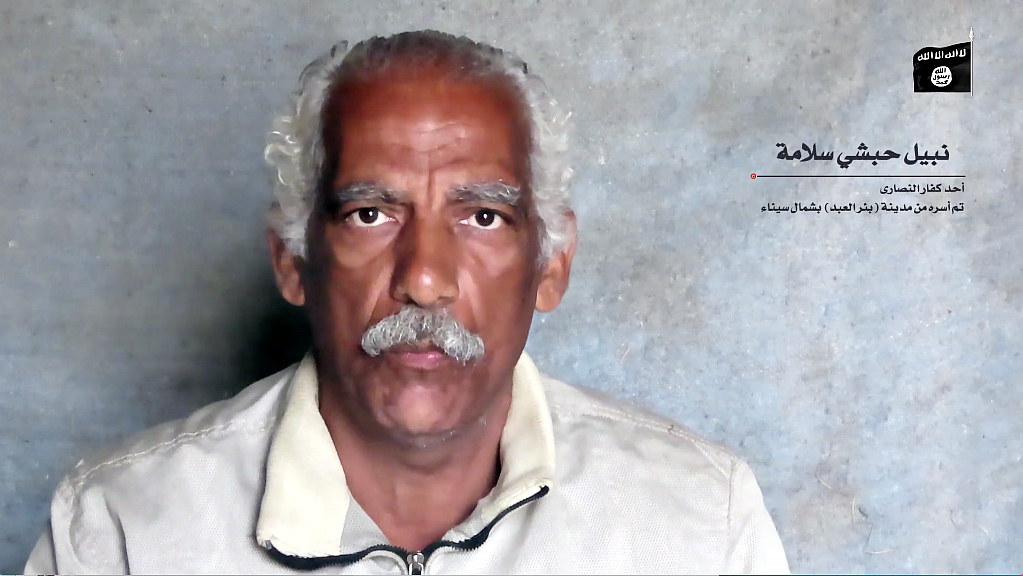

The Islamic State has claimed another Christian victim.

And Egypt’s Coptic Orthodox Church has won another martyr.

“We are telling our kids that their grandfather is now a saint in the highest places of heaven,” stated Peter Salama of his 62-year-old father, Nabil Habashi Salama, executed by the ISIS affiliate in north Sinai.

“We are so joyful for him.”

The Salamas are known as one of the oldest Coptic families in Bir al-Abd on the Mediterranean coast of the Sinai Peninsula. Nabil was a jeweler, owning also mobile phone and clothing shops in the area.

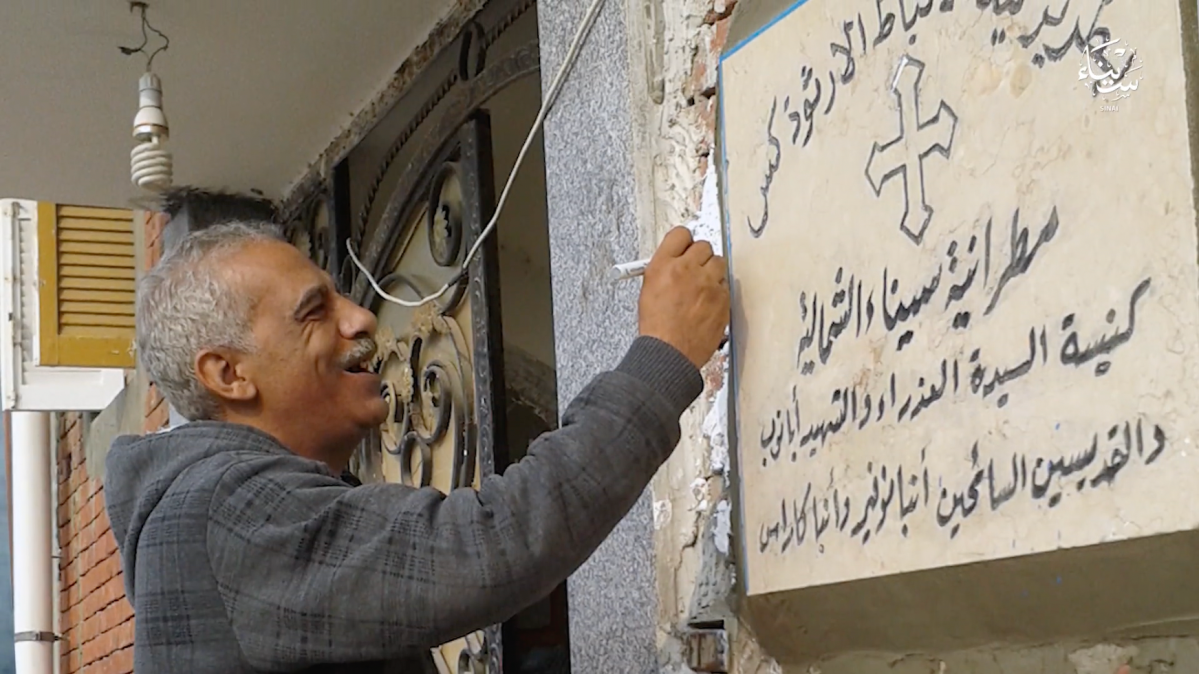

Peter said ISIS targeted his father for his share in building the city’s St. Mary Church.

In a newly released 13-minute propaganda video entitled The Makers of Slaughter (or Epic Battles), a militant quotes the Quran to demand the humiliation of Christians and their willing payment of jizya—a tax to ensure their protection.

Nabil was kidnapped five months ago in front of his home. Eyewitnesses said during his resistance he was beaten badly before being thrown into a stolen car. It may be that these were separate kidnappers, because in the video that shows Nabil’s execution, he said he was held captive by ISIS for 3 months and 11 days.

On April 18, he was shot in the back of the head, kneeling.

“As you kill, you will be killed,” states the video, directed to “all the crusaders in the world.”

It addresses all of Egypt’s Christians, warning them to put no faith in the army. And Muslims which support the Egyptian state are called “apostates.” Two other Sinai residents—tribesmen who cooperated with the military—are also executed in the video.

Peter Salama said that in the effort to drive Nabil from his faith, his teeth were broken.

Nabil’s daughter Marina joined in the tribute.

“I will miss you, my father,” she wrote on Facebook. “You made us proud during your life with your virtues, and in your martyrdom with your strong faith.”

The Coptic Orthodox Church issued an official statement, calling Nabil “a faithful son and servant” who “adhered to his religion until death.”

It then reiterated support for the Egyptian army and state. Such acts, it stated, will “only raise our determination … to preserve our precious national unity.”

Earlier this month Egypt announced an additional 82 churches had been legalized, increasing the total to 1,882 since a corrective law was passed in 2016.

Three militants have been killed, with three others being pursued, stated the Ministry of Interior today, which referred to Nabil as a “citizen.”

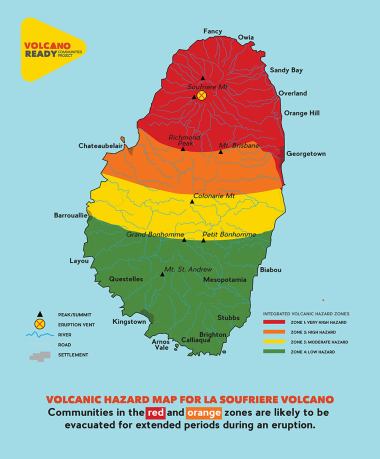

But the video and execution raise fears of renewed ISIS activity after a relatively long period of quiet. In 2017, the affiliate opened fire on Muslims praying in a Bir al-Abd mosque, killing over 300 in the deadliest terrorist attack in modern Egyptian history.

That same year, they also targeted Christians living in nearby Arish, driving over 100 families from their homes.

Since then, the Egyptian army launched a massive campaign to defeat the local ISIS branch, which has never managed to seize and hold territory. In 2018, state security announced that over 900 militants were killed.

In 2019, Christian families slowly began to return, though no hard numbers were available at the time of publishing. In 2012, Coptic Orthodox Bishop Cosman stated there were 740 Christian families in his North Sinai diocese. But prior to the exodus, church officials stated the total was down to only 160.

Today, the women wear head coverings so as not to stand out as Christians. After informing authorities of a ransom demand of $318,000 (the Associated Press reports $127,000), Peter said, state security told him and his family to relocate for safety.

“We live in ruins after closing our means of subsistence,” he told the Coptic publication Watani.

Two other Copts, kidnapped in Sinai last year, were recently released after the payment of ransom.

“President Sisi has been personally committed to promoting peaceful co-existence between Christians and Muslims in Egypt, and his government has taken some encouraging steps,” stated Mervyn Thomas, president of Christian Solidarity Worldwide, offering his condolences to the Salama family.

“[But] abductions … highlight that far more must be done to uproot sectarianism, protect vulnerable communities, promote social cohesion, and uphold fundamental human rights for all Egyptians.”

Meanwhile, the president of the Protestant Churches of Egypt echoed the sentiments of the Coptic Orthodox.

“Together with the Egyptian state, we face all challenges and evils with zeal,” Andrea Zaki told CT, “and we always and forever affirm our authentic Egyptian unity.”

Peter Salama, however, focused on eternity.

“Do not think that I am building this church for here,” he recalled his father Nabil saying. “I am building for myself a home in heaven.”

And it was this peace that allowed Nabil to tell his son prior to his execution, while under the duress of his captors:

“All is fine, thank God.”