In recent years, both The Guardian and The New York Times have featured lengthy exposés of orphanages in the majority world. It appears that many orphanages have been run for nefarious ends. There have been reports of children being trafficked into orphanages either in return for financial benefit to impoverished parents or merely on the promise of a better life for their children. There is also evidence that in some of the worst cases, children have then been sexually and physically abused in the orphanages or sold on to be exploited by others.

Cases like these have led Australian Senator Linda Reynolds to campaign from within the Australian government for action on orphanage tourism and to lobby for “orphanage trafficking” to be classed as a new crime under the legislative umbrella of Australia’s Modern Day Slavery Act. Christians have been implicated in these terrible abuses, as the exposés reveal that churchgoers worldwide have been financially and practically propping up the global orphanage system over many decades, potentially making children more vulnerable to exploitation.

Personally, I have found reading these articles incredibly tough—for a whole variety of reasons. My mother spent some of her childhood in an orphanage in India. My wife’s grandparents ran a well-respected children’s care home. I began fostering and adopting children 13 years ago. I am the founding director of a charity working specifically with vulnerable children and I regularly consult for large Christian NGOs.

Additionally, members of my local church and more than a couple of friends currently live in or have been raised in institutions. Many more friends and church family support orphanages around the world. Some of them have even helped start orphanages. Over the years, I have given significant practical help, prayer, and financial support to them and to various young people going out on short-term orphanage projects. Ever since my wife and I first met nearly 30 years ago, we have dreamed about pulling our experience together and spending our retirement running an orphanage in Africa or Asia. The last thing I want to hear is that I could be doing more harm than good by trying to help vulnerable children around the world.

Like many, I take the challenges raised by the development sector very personally. For those of us who have invested our lives into this area of Christian service, the temptation is to insulate ourselves from criticism by retreating from the conversation or fighting against the critique. But I also know from years of working in the field of child protection that we must face up to the facts, research any allegations, and ensure we are putting the welfare of children before our own ego, mission or dreams. History is sadly littered with well-meaning Christian interventions that went badly wrong, with many of them covered up for generations.

Christianity and Orphanages

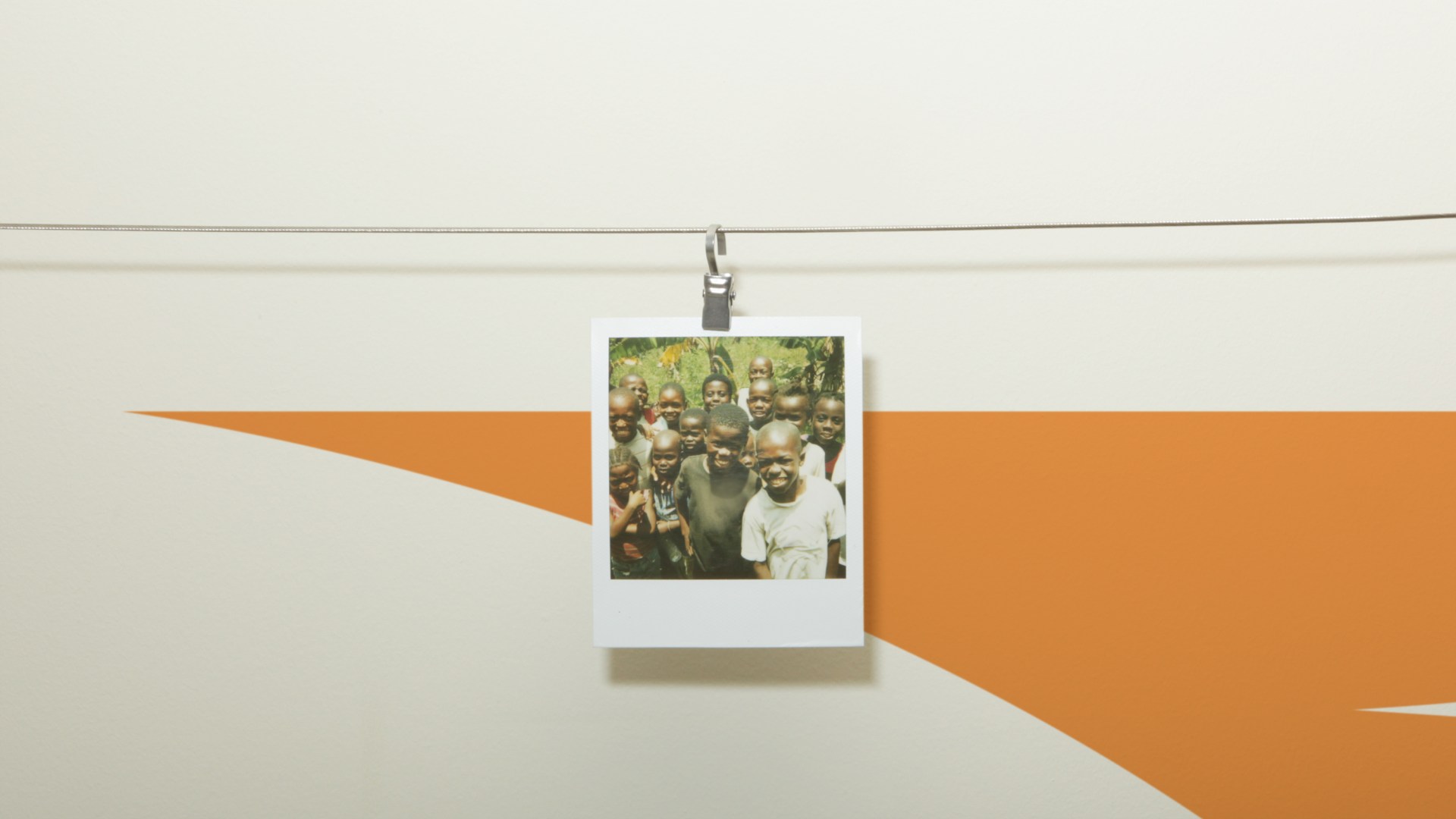

According to figures from the United Nations, by a conservative estimate, there are around 8 million children living in orphanages around the world. Additionally, there are over 70 million people living as refugees or internally displaced due to war, conflict, and natural disaster and many of these are children who have lost parents or family or both. There have also been many children affected by the AIDS epidemic, and even today despite huge economic advances around the world, children are over-represented among the “bottom billion” poorest people. According to UNICEF, there could be as many as 140 million children around the world .

With such shockingly huge statistics, it is not surprising that occasionally terrible reports emerge. However, it does seem rather extreme to react by suggesting that all orphanages should be shut down because of isolated cases of trafficking and abuse. Is it simply a case of finding an angle to scapegoat Christians?

It should not surprise us that Christians are highly involved in a response to the global challenge to help vulnerable children. There are more than 40 occasions where the Bible refers specifically to God’s concern for orphans or the fatherless (Deut. 10:17–18, 24:17, 27:19, James 1:27, etc).

Historically, Christians have also often been at the forefront of the care, protection, and championing of vulnerable children. Until now, many people have seen Christian orphanage support as a key component of championing the cause of the most vulnerable.

My charity, Home for Good, conducted a parallel study among British adults, asking 6,000 people for their perceptions and practices regarding the support of orphanages. We found that churchgoers were seven times more likely to support an orphanage through visiting or volunteering than other British adults. It is undoubtedly true that the world’s orphanages owe much to Christian support. But whereas orphanages used to be seen as an honorable cause, they are now being implicated in a global scandal.

Institutions and Scandals

The term orphanage is elastic. It can describe large-scale institutions like the City for Human Welfare in Turkey that cares for almost 1,000 children—mostly victims of the war in Syria. But it can also be applied to a small group home where just a handful of children live under one roof. And there is a range of models in between including children’s villages, residential care centers, compound foster care, shelters, and rescue homes. I had always assumed that the larger the orphanage, the worse the conditions; however, recent research seems to be pointing the finger at smaller institutions as well as larger ones.

What is now being understood across the development community, and by child psychologists, social workers, and child protection experts is that an institutional culture can be found even in smaller, modern orphanages. Signs might include organizational regimes and routines that take little account of individuality, places where psychological and emotional needs are left unmet, or homes that tend to isolate children from the outside world. The impact of this may not be as visually shocking as images of rocking toddlers left in cots in rooms without windows. Yet the invisible impact of veiled institutionalization may be just as severe.

The long-term effects of institutionalization are what lie behind the suggestion that orphanages may be doing more harm than good. And this has caused me to start rethinking orphanages too.

At the conclusion of her TED talk “The Tragedy of Orphanages” Georgette Mulheir, CEO of LUMOS, states:

But there is still much to be done to end the systematic institutionalization of children. Awareness-raising is required at every level of society. People need to know the harm that institutions cause to children, and the better alternatives that exist. If we know people who are planning to support orphanages, we should convince them to support family services instead. Together, this is the one form of child abuse that we could eradicate in our lifetime.

Is there a better alternative?

But are all orphanages really only abusive environments that need to be eradicated?

While I have seen evidence that does indeed suggest that some orphanages are fronts for child trafficking and child exploitation, it is blatantly unfair to tar all orphanages with that same brush. Many orphanages, faith-based or secular, are well-managed, financially accountable, and run by sensitively trained staff who desire the children’s best outcomes.

In the best cases, orphanages are indeed trying to keep children safe, nourished, clothed, and educated. I have heard stories from children living in orphanages who were abandoned, sleeping rough, begging, or being used as child prostitutes. It was an orphanage that rescued them, providing shelter, safety, food, and drink.

However, just because a lifeboat is a safer alternative to drowning in the sea does not mean those who have been rescued want or need to live on a lifeboat for years on end. Similarly, just because an orphanage may be safer than trying to survive on dangerous streets does not mean orphanages are the long-term solution to the problems facing vulnerable children.

When it comes to vulnerable children, I have seen that the best place for them to thrive is in the context of a permanent loving family. If anything were to happen to my wife and me, we have made arrangements for our children to be taken under the wing of a family as close in values to our own as possible, not go to an orphanage or a residential home or foster care. A true sense of family cannot be replicated in institutional care. In the West, residential care is used sparingly and only when other care options have been exhausted.

Orphanages can do good, but they are not a good solution to the problems facing children without homes. Rebecca Smith, senior child protection advisor at Save the Children, told me, “There are better and worse orphanages, but there is no such thing as a good orphanage.”

The Kaduna first lady of Nigeria, Hadiza El-Rufai, agrees. Visiting an orphanage for 24 children that her husband’s government has just renovated, she might have been expected to sing the praises of her country’s care system. Instead, she said: “No matter how well run an orphanage is, we really do not want our children to grow up there; it can never be as a child growing up in a family with mother and father.” She went on to call on Nigerians to step up as potential adoptive families.

There are two main family-based alternatives to orphanages. The first one is reunification with birth and extended families. The viability of this option would need to be assessed with the child’s safety, security, and best interests in mind. There may be a need for professional, therapeutic support to be put in place or for financial capacity building to be in place around the family.

If this is not possible, a second option is reparenting through locally approved foster carers or adopters. This is the preferred option in the Western world when birth families are not able to provide appropriate care, but it also has an ancient and international tradition.

Some say that this kind of global sea change from orphanages to family-based care is unrealistic and naïve. But unrealistic and naive was what William Wilberforce was accused of when he started to fight the transatlantic slave trade. This movement toward family-based care is the next logical step on the innovation journey.

The myth holding us back

A common response to this call for the end to orphanages is to ask, “Don’t orphanages exist precisely because there are no families to take care of the children?” This assumption is a myth that needs to be addressed. Research conducted by Faith to Action discovered a shocking reality: The majority of children living in orphanages across the globe still have at least one living parent! Their study found that 95–98% of children living in institutional care in Eastern Europe and Central Asia had parents who felt they could not care for them and therefore placed them in orphanages. The research also suggests that, with some help, these families could care for their children.

The term orphanage is therefore somewhat of a misnomer when it is filled with children who have living parents. Nevertheless, there are significant pull factors that encourage families to relinquish their children to orphanages. This may be for financial gain for the parent or the child. In areas of extreme poverty, parents may feel they are giving their child a better start in life to be supported by Western donors who will pay for a lifetime of food, medical expenses, and education. Some reports indicate that certain profiteering “orphanages” who rely on a “full house,” or who gain financially from large overseas adoption fees, may even pay parents to relinquish their children.

Kate Van Doore, a lawyer and international children’s rights campaigner, gave me this sobering assessment: “Orphanages do not exist because orphans exist. Rather orphans exist because orphanages exist.”

All of this amounts to both good and bad news. The bad news is that some children are needlessly being placed into orphanages. The good news is that with the right processes, we could significantly reduce the number of children living in orphanages in our lifetime.

Should we stop supporting orphanages?

After the sexual abuse and harassment scandals that hit both Oxfam and Save the Children in 2017, there was such a huge backlash against all aid and development agencies that some people ceased to support not only those charities but any development charities. A knee-jerk reaction is not helpful; we instead need to bring, wisdom, humility, and nuance to these issues, particularly regarding money.

I remember, as a young missionary in Albania, literally finding a baby abandoned on the street one November evening. The child was wrapped in a dirty sheet and next to it was a pot for coins. I knew a couple of coins was not going to save this child from freezing, so I did what I felt was my Christian duty and picked up the baby to take it to the nearest orphanage.

Within seconds, a woman appeared out of nowhere and snatched the child back before holding her hands out for money. This parent was so desperate that she was using her child as financial bait. The generosity of strangers was not helping the problem of street children but rather exacerbating it.

A number of orphanages have deliberately put themselves on tourist routes to entice people to treat them as another excursion: safari one day, orphanage tour the next. Tourists are encouraged to play with the children, then give them gifts or make a donation. Some of these orphanages were found to be exploiting the children, lining someone’s pockets and not helping the children at all. The Westerners were being conned. They thought they were doing some good, but really they were being used as pawns in the exploitation of the children.

I am not suggesting we all stop funding orphanages today. I am definitely not suggesting we stop caring for the plight of vulnerable children around the world. But it is time to face up to the questions being asked of us. Are we being manipulated? Are we meeting the real needs of the children? Are the orphanages really profiteering ventures in disguise? How can we best channel our finances so that children really benefit?

Is giving time better than giving money?

I have good Christian friends whose children have volunteered at an orphanage for a summer or a gap year. It seems such a good thing to do. They are investing their time and energy in the well-being of children, giving them human connection, affection, and attention. The young people come home changed. Their eyes are opened to needs beyond their own. Their values and sometimes their career plans are shifted. Everyone seems to be a winner. The orphans are entertained, the orphanages are encouraged, and the young people are inspired.

My perspective on this being a “win-win” has shifted, however, after hearing about the steady stream of tourists (often hundreds in a week) who visit orphanages to play with the children. In one orphanage in China, some visitors pop in for an hour or two. Others for a week or two. At another orphanage, I heard from a young volunteer that she was allowed to take a small baby home with her for a few days. The common factor with all the volunteers was that they left the project feeling like they’d done something good, but the children they were trying to help ended up feeling abandoned—again and again.

There is evidence from attachment theory that shows that children living in orphanages already have difficulties making appropriate trusting relationships because of early trauma or abandonment. Having suffered a major broken attachment from birth parents, what children need most for their healing is consistency of relationship and care. Having random strangers come and go in their lives will be repeatedly traumatic and could be far more detrimental than we could ever imagine.

Just as we might need to rethink the way we use our finances to help vulnerable children, we may also need to rethink the way we use our time when it comes to offering support to vulnerable children. Are we just “voluntourists” who have little expertise in understanding the psychological, emotional, and cultural needs of children in orphanages? Who does the whole experience benefit most? What may be some of the unintended consequences of our short-term programs? Could the money we would have spent on our own experiences be better utilized in different ways?

What should the church do?

There are three negative reactions that this article may provoke.

Firstly, I am nervous that Christians who are currently supporting orphanages and children’s villages around the world will immediately stop funding these initiatives. The sudden drop in funds is likely to make children more vulnerable as it could lead to unplanned and unmanaged transitions for children. Please instead use the financial power and influence you have as a donor to encourage the institutions you support to redirect their efforts toward family-based care with the best possible outcomes for the children involved.

Secondly, I am nervous that Christians will ignore this article and this movement and hope against hope that the institution they support is the one institution that has got it right. Please at least ask the questions so you can have a clear conscience that the children you are supporting are not put at risk and get the best outcomes possible.

Thirdly, I am worried that Christians will fight to preserve orphanages despite the evidence, and that this will not only potentially be bad for children but also bad for the church, reinforcing the stereotype that Christians are naïve do-gooders. Bearing in mind the child-abuse scandals that have plagued the church over the last few decades, please, could we instead make sure that we care more about individuals than we do about institutions, more about the well-being of children than the reputation of the church?

My wife and I need a new dream for our retirement. It will still be founded on making one small corner of our world better for vulnerable children. But instead of helping to open an orphanage or two, maybe now we will help to close an orphanage or two and ensure the children are safely placed in families where they can thrive.

Krish Kandiah is the founding director of Home for Good, a charity dedicated to finding a home for every child who needs one. Krish has wide experience in the fields of cross-cultural mission, aid, and development. He helps to catalyze a wide range of Christian and secular agencies to work together for the best outcomes for vulnerable children around the world. For more information, visit homeforgood.org.uk and homecomingproject.org