On June 2, as protests over the death of George Floyd raged across the United States, President Donald Trump elevated the stature of religious freedom within the State Department.

“Religious freedom for all people worldwide is a foreign policy priority,” read the executive order (EO) he signed, “and the United States will respect and vigorously promote this freedom.”

It received almost no media attention.

The provisions—long called for by many advocates of international religious freedom (IRF)—could overhaul a US foreign policy that has historically sidelined support for America’s “first freedom.”

That is, if the order survives a potential Joe Biden administration.

It is common for a new president to reverse EOs issued by their predecessor. In his eight years in office, President Obama issued 30 to amend or rescind Bush-era policies. In his first year in office, Trump issued 17 directed at Obama-era policies.

While IRF has typically enjoyed bipartisan support, current political polarization leaves few sacred cows.

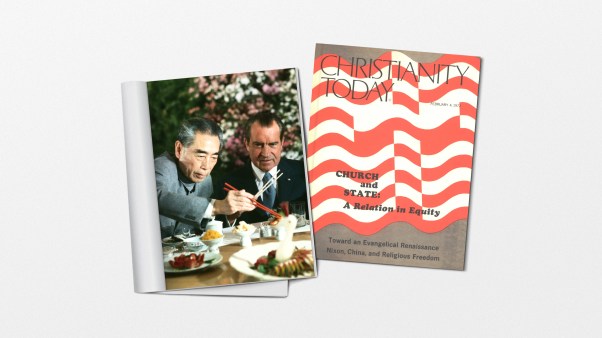

Trump signed the EO after a visit to the Pope John Paul II National Shrine in Washington, DC. It was previously scheduled to coincide with the anniversary of the Polish-born pope’s 1979 return to his home nation, which set off a political and spiritual revolution that defied the Soviet Union and eventually ended the Cold War.

However, Washington’s Catholic archbishop called it “baffling and reprehensible” the facility would allow itself to be manipulated one day after Trump lifted a Bible in front of St. John’s Anglican Church across from the White House in the wake of the aggressive dispersal of protesters opposing police brutality and racial injustice.

The president’s gesture risked corroborating critics who argue that Trump’s religious freedom policies are a nod only to evangelical Christians concerned for fellow believers.

But while the Bible photo op divided evangelicals, should Trump’s IRF credentials definitively tilt the scale come elections in November?

“President Trump’s executive order will make the commitment to international religious freedom more robust,” said former congressman Frank Wolf, arguing the Trump administration has been markedly stronger on the issue than those of either party.

“If you care about religious freedom, this is an issue to vote on.”

Wolf, a Republican from Virginia who retired from the House in 2015 after 34 years of service, was a forceful advocate for the 1998 International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA). The bill, passed 98–0 by the Senate, provided for an ambassador-at-large position, responsible for producing an annual State Department Report on International Religious Freedom, and designating violators as “Countries of Particular Concern.”

It also created the independent and bipartisan US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), to advise on foreign policy.

A third provision, for a special advisor on IRF to serve at the National Security Council, went unheeded until February this past year, when Trump appointed Sarah Makin to the position.

A 2016 amendment to IRFA, named in honor of Wolf, re-clarified that the ambassador-at-large must report directly to the secretary of state. Some did not respect this arrangement, following presidential delays even to fill the position. George W. Bush presented his candidate 16 months after assuming office; Barack Obama waited 28 months.

By contrast, Trump nominated current ambassador Sam Brownback, previously the Republican governor of Kansas, only six months into his term.

“The US government has slow-walked international religious freedom,” said Paul Marshall, professor of religious freedom at Baylor University’s Institute for Studies of Religion.

“It is a difficult and sensitive issue, raises tensions with other countries, and tends to get siloed within the State Department.”

Wolf stated that under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the department resisted declaring Nigeria’s Boko Haram a terrorist organization. It viewed this issue through an economic lens only.

Under current Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, however, Nigeria was listed for the first time as a Special Watch List nation.

Trump’s EO authorizes a minimum of $50 million for programs to advance IRF through the prevention of attacks on religious minority communities as well as the preservation of pluralistic cultural heritage.

It also stipulates there must be no discrimination against faith-based entities in funding awarded through the State Department’s US Agency for International Development (USAID).

Vice President Mike Pence’s 2017 pledge to directly assist beleaguered Christian communities in Iraq serves as a case-in-point why Trump’s EO will be helpful. Eight months later, no funds had been distributed.

“Many State Department officials have a religion deficit in knowing how to engage,” said Chris Seiple, who serves as a senior advisor for the Center for Faith Opportunities and Initiatives at USAID.

“They don’t have the skill set, and fear it could risk their career if they violate the religious establishment clause [of the First Amendment], so they back off.”

USAID likes to give big grants to large organizations with a proven track record, Seiple said, but this runs against current wisdom in development circles, which emphasizes local actors. And around the world, these are often people of faith.

Seiple, also president emeritus of the Institute for Global Engagement, said better development comes when communities work together across religious divides in a respectful, robust pluralism.

A new analysis of a 2018 survey by the Pew Research Center, released this month, found a 15-point increase in the favorability rating by Hindus toward Muslims in India, from 56 percent to 71 percent, if they reported frequent interaction together.

In the Philippines, Christian favorability towards Muslims increased from 50 percent to 61 percent. And in Lebanon, already favorable Sunni Muslim attitudes towards Christians improved from 81 percent to 87 percent.

“Harness self-interest,” said Seiple. “If there is a serious religious divide and yet officials bring peace and development, they will get a good job evaluation.”

Wolf wants to see this same attitude at the State Department. For years, he said, he pushed for greater IRF training and the creation of a career track.

The 2016 IRFA amendment made such training mandatory for all foreign service officers (which today number about 8,000) before deployment overseas. But it took time to develop the resources.

An Obama administration fact sheet on its efforts to promote and protect IRF stated it “dramatically increased” such training, to reach 330 diplomats and embassy staff.

In 2019, Trump’s administration developed and launched an IRF distance learning course, also made available as an elective (described in Appendix E of this year’s IRF report).

According to the State Department, since the Wolf Act’s implementation, more than 10,000 employees have completed IRF training.

Trump’s EO expanded the training to include an additional 2,000 State Department civil service personnel.

It also added a deadline.

Within 90 days of the order, all heads of agencies assigning overseas personnel must detail their plans to ensure IRF training is conducted before departure, as well as in three-year cycles.

“This executive order could massively expand the number of people taking training on international religious freedom,” said Judd Birdsall, director of the religion program at Cambridge University’s Centre for Geopolitics.

Birdsall, a former diplomat in the State Department’s Office of International Religious Freedom, worked under both Secretaries Condoleezza Rice and Clinton. In 2011, he helped to design the department’s first training course on religion and foreign policy.

Birdsall said that several Obama officials were initially “highly skeptical” of his office, viewing it as an “evangelical outpost.” This was unfair, he said, because the diverse staff promotes the rights of people of all beliefs.

Even so, the timing of Trump’s EO will reinforce the perception.

“This is a plank-in-your-own-eye moment for America,” Birdsall said. “Its release amid the unrest made the executive order look like a diversionary tactic.”

Kent Hill, senior fellow for Eurasia, Middle East, and Islam at the Religious Freedom Institute (RFI), believes similarly.

Though “tragic” in its timing, the EO “embraces universal values and ought to enjoy tremendous bipartisan support,” he said.

“It is imperative that Americans disentangle their feelings about this administration—pro or con—and recognize [the order’s] exceptional importance.”

His colleague Jeremy Barker, director of the Middle East Action Team at RFI, centered the importance on a second EO-stipulated deadline.

Within 180 days of the order, the Secretary of State must develop a plan, in consultation with USAID, to prioritize IRF in US foreign policy. The secretary will furthermore direct US embassies to write “comprehensive action plans” on how it will encourage local governments to eliminate religious freedom violations.

The deadline will expire in December, one month after the 2020 presidential election. Might foreign service bureaucrats drag their feet until they know the outcome?

Barker thought it would be unlikely for Biden—one of the 98 senators to endorse IRFA—to rescind Trump’s EO, given the issue’s long history of bipartisan support.

After all, IRFA was signed by President Bill Clinton, he noted; the 2016 amendment, by Obama. And Nancy Pelosi lent her aid to Trump’s second Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom.

But scholar Elizabeth Prodromou, appointed by Pelosi as a commissioner on USCIRF from 2004–2012, thought it possible, “even likely,” that State Department officials might take a wait-and-see approach—not for political reasons, but simply because there is too much institutional inertia.

The government treats IRF as important, she said, but not always as a priority.

But a Biden administration, Prodromou anticipates, would not abrogate the EO, as she believes the presidential candidate appreciates the linkages between religious freedom and national and human security.

Having served as a member of the State Department’s Religion and Foreign Policy Working Group under Secretaries Clinton and John Kerry, she pushed back against the idea that Trump has been better on IRF than other presidents.

Across administrations, Prodromou said, there has been a growing realization that national security must incorporate a commitment to civil and political liberties—inclusive of religious freedom.

In recognition, the Obama fact sheet stated his administration allotted more personnel, resources, and funding to IRF than any president since IRFA was established.

In 2013, Obama created the Office of Religion and Global Affairs (RGA) in order to include an international religious perspective not only on traditional “security” concerns, but also on development, gender rights, and climate change. He additionally created a special envoy to represent the US at the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Trump’s first Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, eliminated the position, and controversially condensed the RGA office into the IRF office.

But while Prodromou praises the EO and Trump’s IRF promotion in general, the problem lies in the conflation of message and messenger.

“This executive through his language disrespects human dignity, and unfortunately the perception of confessional bias undermines his impact,” she said, mentioning issues of immigration and the rhetoric employed against ethnic minorities.

“Paradoxically, the President’s statements weaken the possibility and great potential for these [IRF] measures to have lasting positive outcomes.”

Birdsall suspected that a Biden administration would look much like Obama’s inclusion of IRF within a broad human rights agenda. Operating from England, he said much of Europe is suspicious of Trump’s approach.

Birdsall highlighted one of Trump’s signature accomplishments—the creation of an International Religious Freedom Alliance launched with 27 nations. It includes Hungary and Poland, two nations cited for violations in the annual State Department report and whose reputation in Europe is souring.

But while Trump’s EO was praised by Christian leaders in Syria, Iraq, and Nigeria, the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA) voiced overall concern.

“We are grateful for US leadership in the defense of religious freedom, and recognize that the Trump administration has been vocal in an unprecedented manner, mobilizing governments worldwide in support,” said Wissam al-Saliby, WEA advocacy officer.

“The current US administration, however, more than those previous, has indicated repeatedly that human rights are far from a foreign policy priority.”

Saliby centered his critique on the US withdrawal from global leadership. He urged America to rejoin the UN Human Rights Council, the World Health Organization, and to stop its attacks on the International Criminal Court.

“US partnership in the multilateral system—prioritizing human rights, hosting refugees, fighting pandemics, illiteracy, and poverty—will give greater credibility and impact to its advocacy on religious freedom.”

But independent of these global bodies, the Trump administration is pushing ahead. A fourth provision of the EO calls for collaboration with the Secretary of the Treasury to advance the cause of IRF.

Tools include economic sanctions, the reallocation of foreign aid, and the restriction of US visas. Though these measures are not new, previous administrations have been reluctant to employ them, regularly exercising waivers for the sake of national security.

And therefore, all steps must be taken in consultation with the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, the position Trump filled for the first time since 1998.

Will this be enough for conflicted voters to check the Republican box in November? Or will the Democratic critique of Trump’s administration undermine bipartisan and lasting approval for his EO?

Perhaps the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC) of the Southern Baptist Convention offers the best approach. Supportive of US foreign policy on IRF while concerned about the timing of the EO amid Floyd protests, Travis Wussow leaves voters to their own conscience.

“We will continue to be missionaries for the gospel in the public square, and a voice on these issues regardless of the national political environment from election to election,” said the ERLC vice president for public policy.

“Whoever is in office, we will continue to advocate for these fundamental freedoms.”