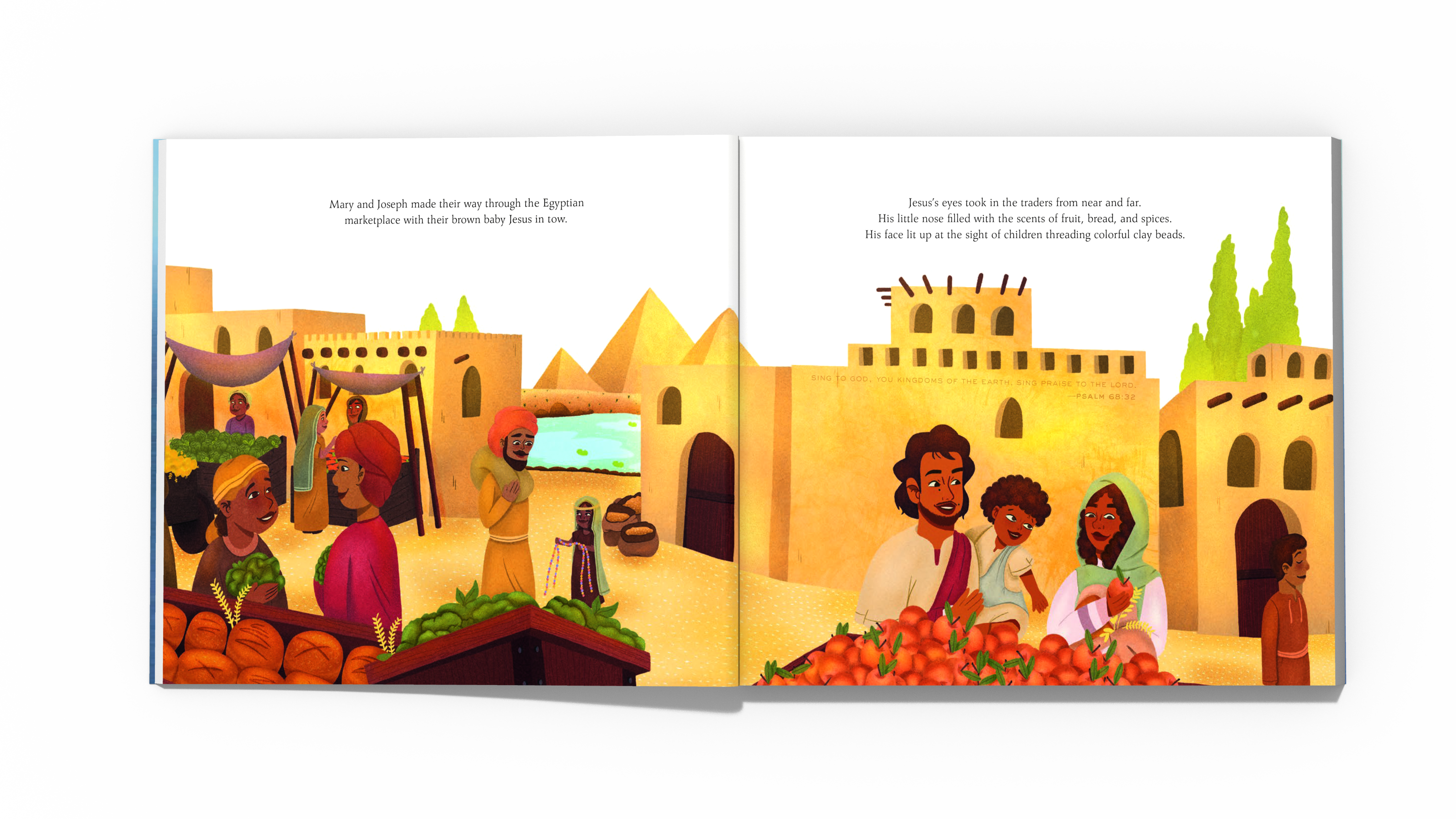

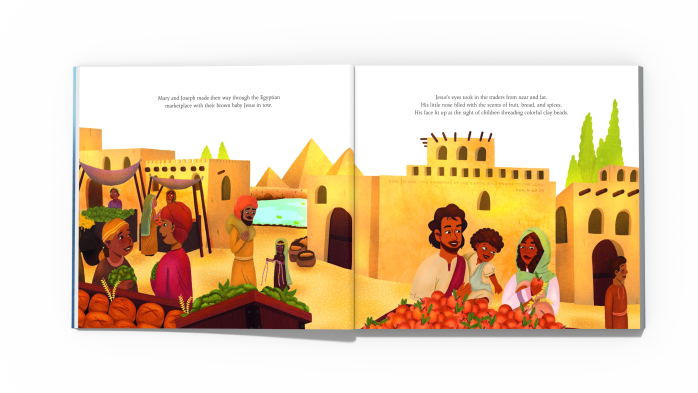

In 2010 I visited the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth and was struck by how different ethnic groups portrayed baby Jesus. From the shape of his eyes to the shade of his skin, each country portrayed Jesus as one of them.

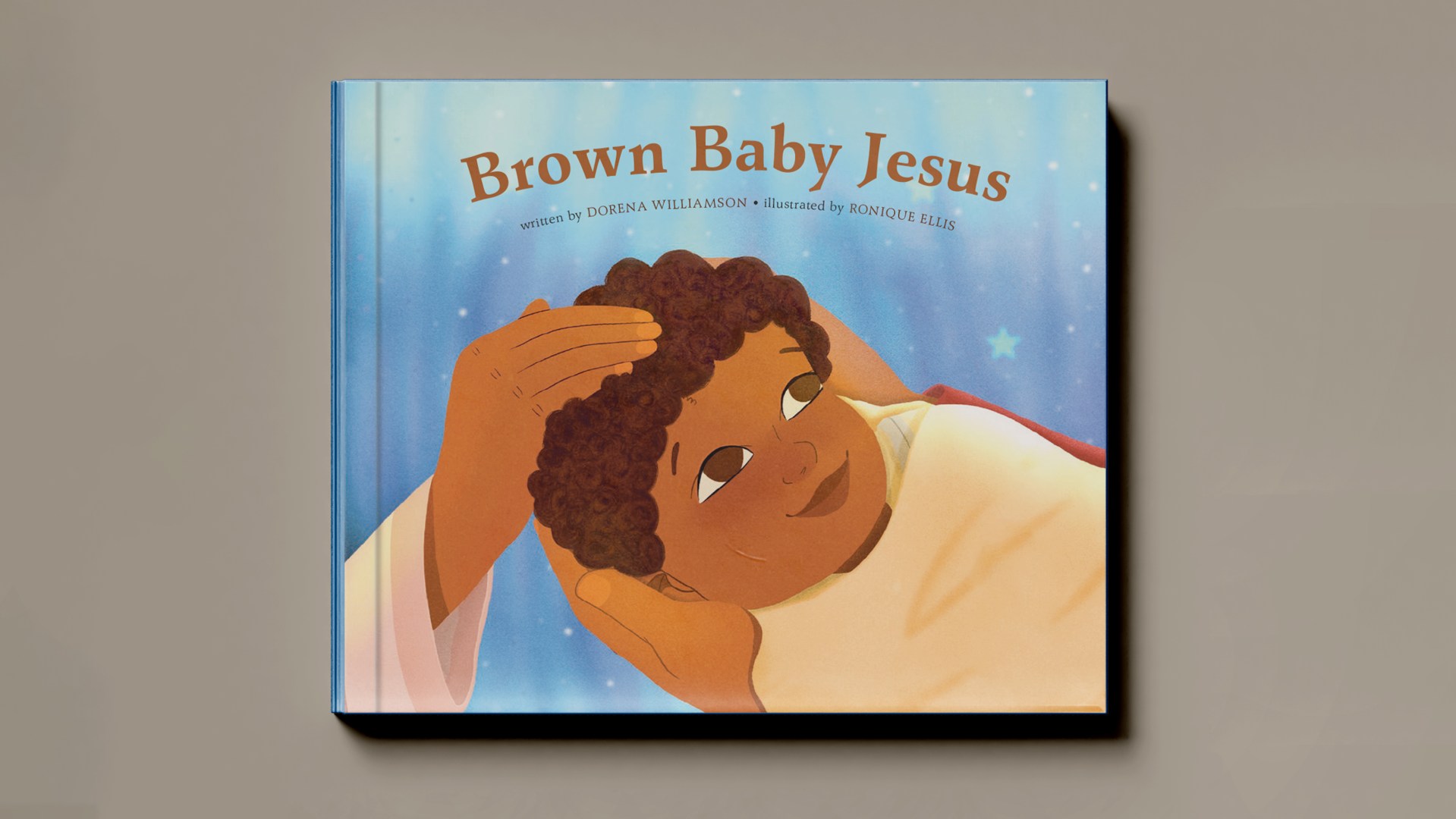

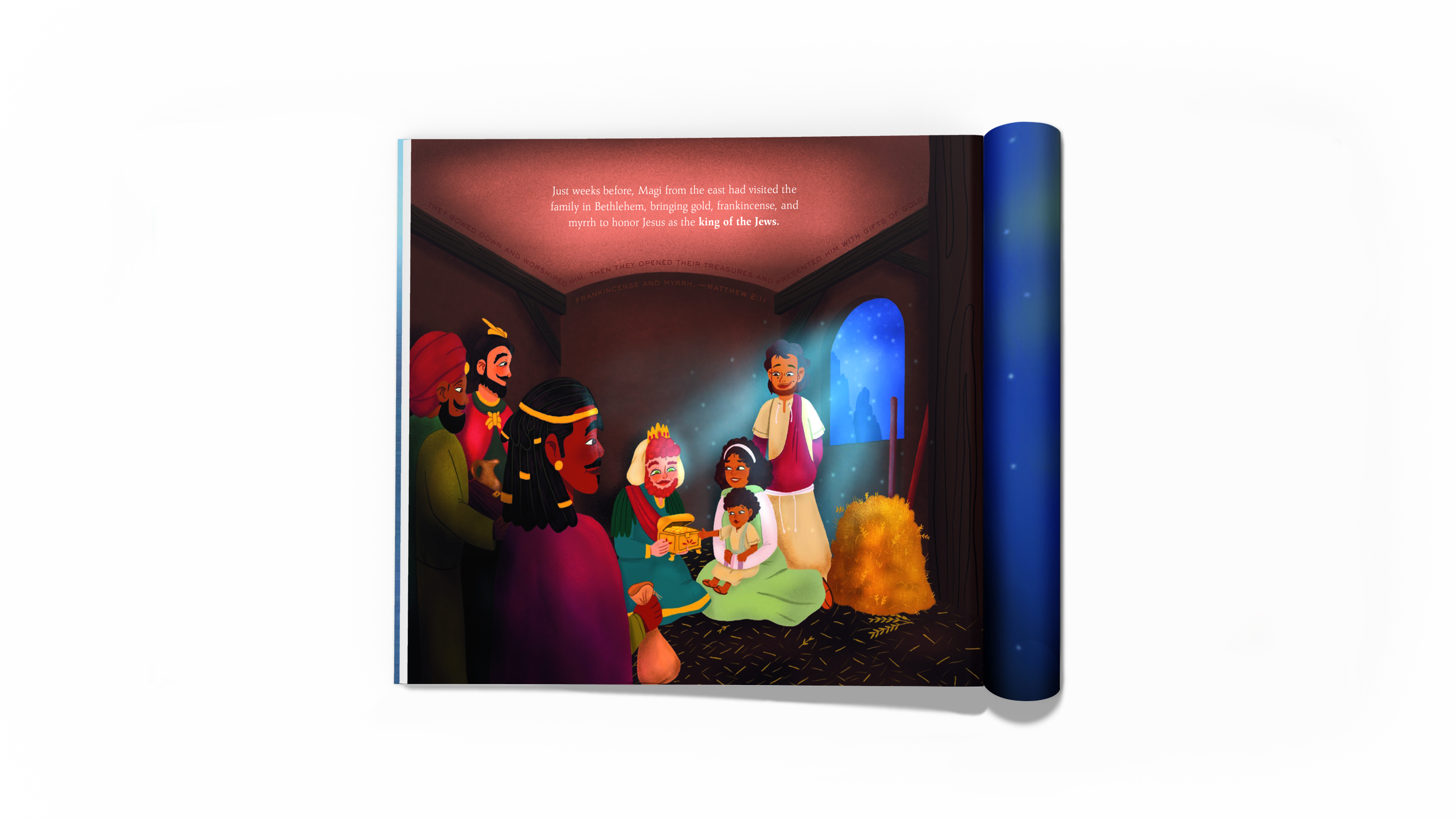

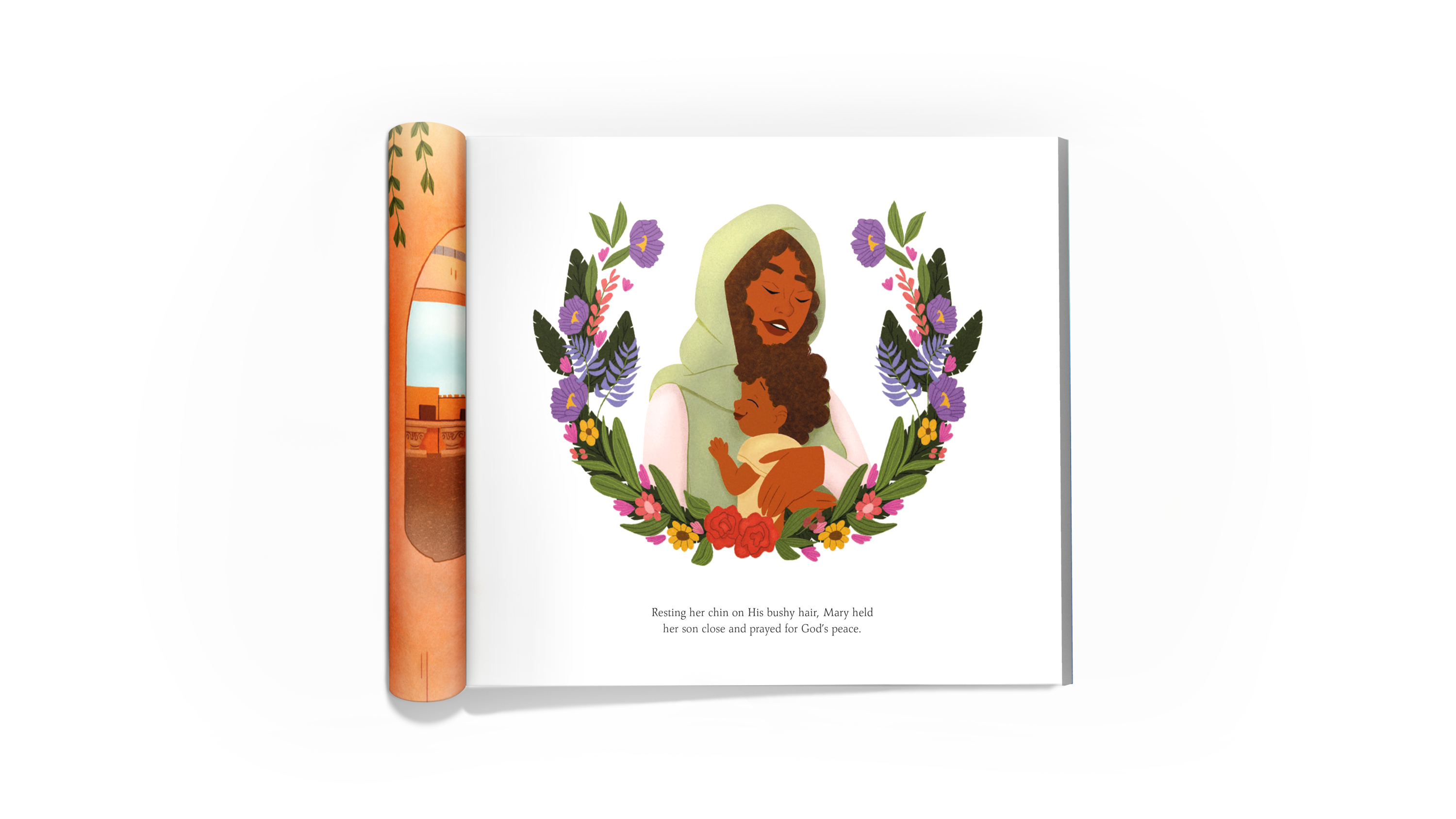

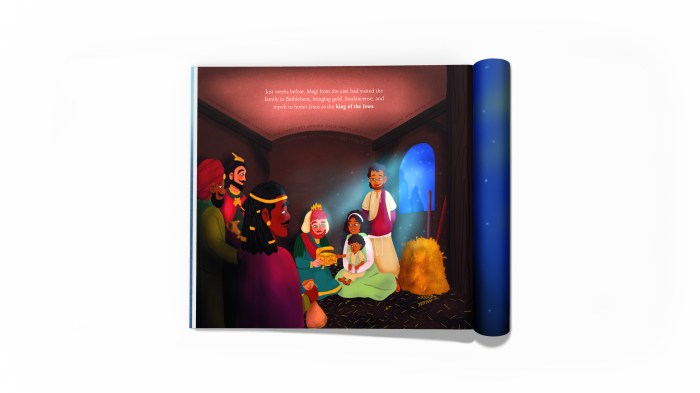

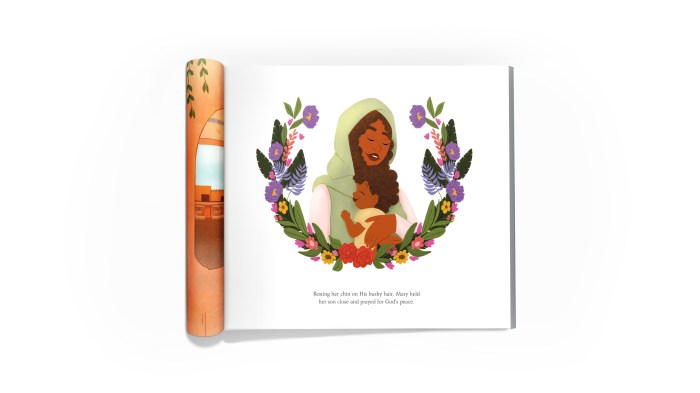

I have always been fascinated by the women God was pleased to include in Jesus’ family tree. Inspired by memories of Nazareth, I longed to disrupt the cultural norm of a white Jesus with a Biblically accurate depiction that celebrates the diverse world Jesus came to save.

Four years ago, a little brown boy at church asked his white mom why everyone made Jesus so white and suggested I write a book with a brown Jesus. I crafted this story so that children like my young friend could see the multicultural weaving of love that God designed in Jesus' family tree.

Excerpted from BROWN BABY JESUS © 2022 by Dorena Williamson. Published by WaterBrook, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, on September 20, 2022. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.