The COVID-19 pandemic is forcing many churches and ministries to rethink how they recruit, train, and maintain the fleet of volunteers they need.

Volunteering for religious organizations dropped during the first year of the pandemic, when in-person services were canceled and outreach events were put on hold, and has continued to decline.

According to Gallup, 35 percent of Americans reported volunteering for a religious organization last year, down from 38 percent in 2020 and 44 percent in 2017.

“A recovery in volunteering may be more elusive as concerns about COVID-19 exposure and public health safety measures limit Americans’ willingness and ability to perform volunteer work,” the researchers wrote.

A lot of churches saw their longtime, reliable volunteers back away from their roles because their age put them at risk, said Chuck Peters, director of the kids ministry team at Lifeway Christian Resources.

Even those who remain willing to serve can be unpredictable; the likelihood of illness or exposure at home, especially during COVID-19 surges, has meant more volunteers are calling out sick when leaders are strapped for help. Plus, church attendance is down overall, though nearly all churches have reopened.

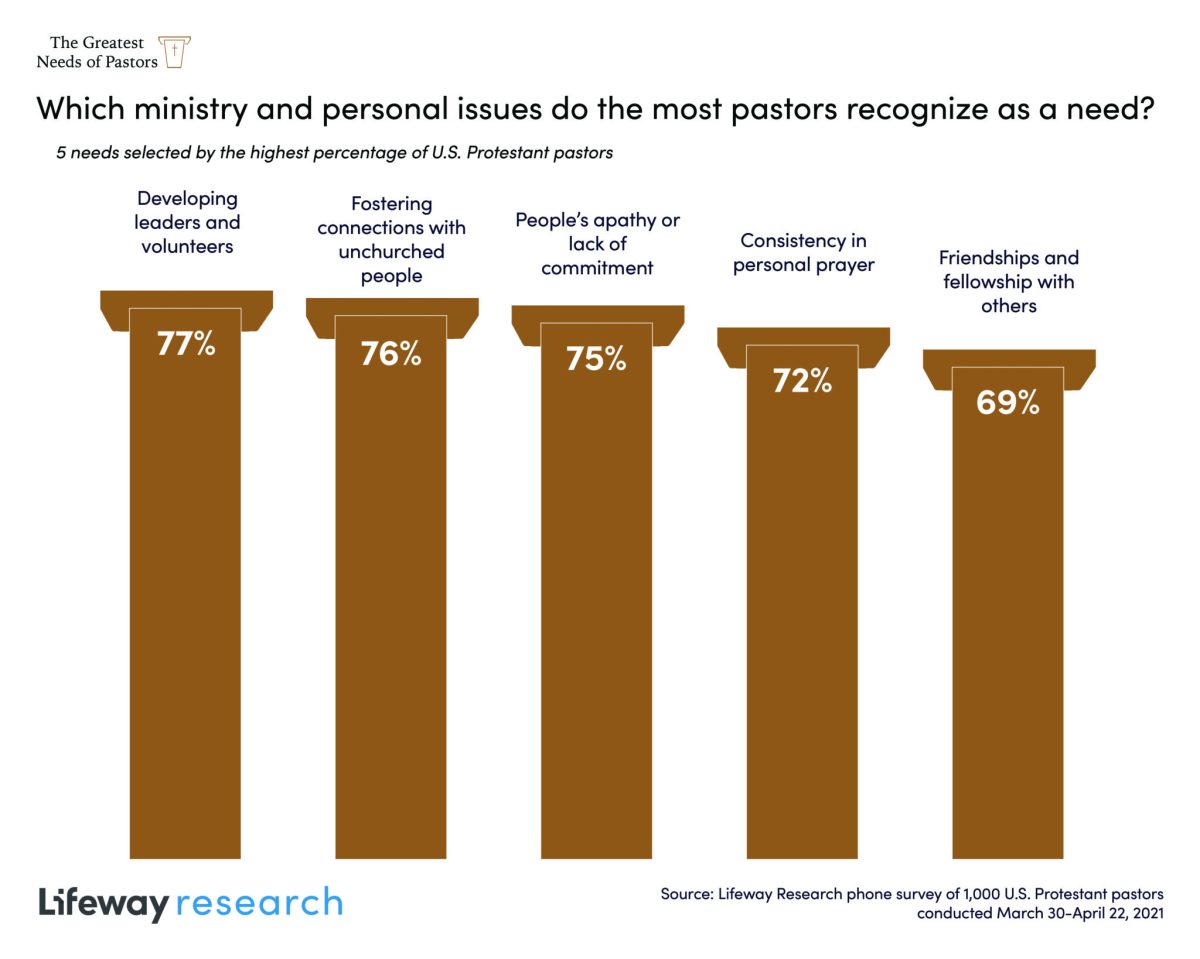

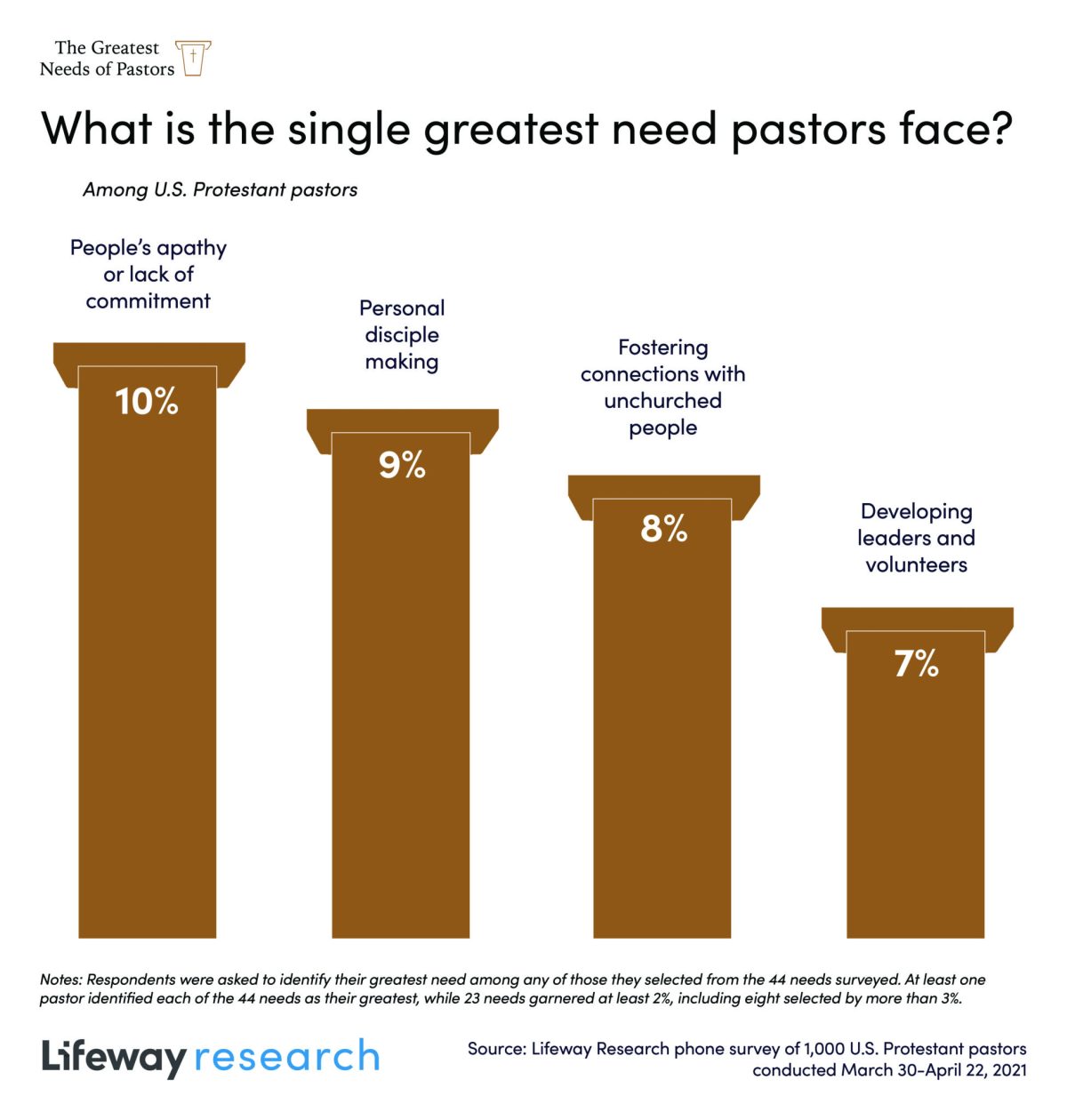

In a Lifeway survey last spring, pastors listed committed volunteers among the biggest needs for their churches. Over three quarters of US pastors said they were concerned about developing leaders and volunteers, as well as people’s apathy and lack of commitment. Over two-thirds said training current leaders and volunteers was a concern.

“A lot of churches lost their long-term, reliable, go-to people and were left with no one. That’s been the challenge. Where do you look now to find a new base of volunteers?” said Peters. “The tendency becomes ask everyone and take anyone. Really, that’s not the best approach … it’s a new opportunity to revisit what kind of volunteers we’re looking for.”

That may mean it’s time to conduct new training, new resources, to rally and prepare volunteers. In children’s ministry, which requires volunteers to serve in roles like teachers, classroom assistants, and security, Peters recommends focusing on the mission of the ministry and the giftedness of the potential volunteers, rather than the desperation for help or obligation to the church.

“Recruit with the why of the ministry, not the need of the ministry,” he said. “In a season where the world is crazy, kids need Jesus more than ever to speak to their fears, and people are experiencing real losses. We have to be faithful to the mission.”

Over in the United Kingdom, a survey by the Evangelical Alliance last fall found 59 percent of church leaders saw volunteering decrease, and 31 percent of church members said they were volunteering less during the pandemic.

Some churches that reopened had not resumed activities in youth ministry (25%) or children’s ministry (17%). Leaders suggested that former volunteers were attending church less and enjoyed having fewer commitments.

Virginia pastor Tom Pounder recommended pastors individually reconnect with volunteers who dropped off the schedule during the pandemic to ask about their concerns and level of interest going forward.

“If we, as ministry leaders, are not connecting with people and letting them know of the variety of different options out there, then we will continue to have a lack of lay/volunteer leaders,” wrote Pounder, student minister and online campus pastor at New Life Christian Church. His church also offers online volunteer opportunities, including chatting with attendees during virtual services.

At the Salvation Army, which runs programs in 7,000 locations in the US, “volunteers have an impact on every aspect of our work,” said Dale Bannon, national community relations and development director.

Some volunteer programs through the evangelical charity were on hold during the beginning of the pandemic, but many have been re-instated with new protocols such as using personal protective equipment and doing contactless delivery to distribute food and supplies.

Christian refugee resettlement agency World Relief moved its volunteer application process and orientation online during start of the pandemic and began offering virtual opportunities, such as English tutoring, youth mentoring, and youth homework help. While in-person volunteering has resumed, the ministry will likely keep some virtual options in the long-term.

“We have found that online tutoring, for example, creates flexibility both for some immigrants and for some volunteers (who in both cases are also balancing job schedules and childcare responsibilities),” said Matthew Soerens, World Relief’s US director for church mobilization and advocacy.

After seeing a drop in volunteers in 2020 due to pandemic shutdowns, World Relief saw unprecedented interest in volunteering last summer, as Americans anticipated Afghan evacuees coming to the US after Kabul fell to the Taliban.

The ministry was able to process the uptick thanks to moving its process online due to COVID-19, as well as more staff dedicated to training volunteers.

“As a result, we had more than 11,000 active volunteers in 2021, far more than in any year in the recent past,” even though the ministry has fewer office locations than it did five years ago, said Soerens. The number of volunteers was twice as many as were involved with World Relief in 2020.

Other ministries have also been able to recruit to meet urgent needs. Last month, Samaritan’s Purse sent 2,000 volunteers to Arkansas and Kentucky after the tornadoes.

But for many nonprofits—from mentoring organizations to food banks—demand is up, and they haven’t been able to find enough volunteers to help.

Volunteering doesn’t just benefit the organizations and their constituents. It’s good for volunteers, too. Returning to serve in person can be a refreshing and much-needed step back into the routines they enjoyed before COVID-19.

Jamie Ivey, author and host of The Happy Hour podcast, recently discussed her involvement with Sunrise Homeless Navigation Center in Austin, Texas.

“Hands down one of the best decisions I made this year was to start volunteering again,” she shared with her social media followers. “In early 2021 I kept feeling like something was off. I know 2020 & 2021 have both been off (understatement of the century) but it was more than the pandemic. Something was off in me.

“If you are feeling off, maybe you need to give some of yourself away each week,” she wrote. “It’s been super healing for me this year!”