Anil’s life took a sudden turn after his mother was miraculously healed following a woman’s simple prayer to Jesus. In this episode of God Pops Up, follow Anil’s journey to learn more about the man who he is convinced saved his mother.

After watching this episode of God Pops Up, read more about Apilang Apum’s call to Christ in a remote corner of India.

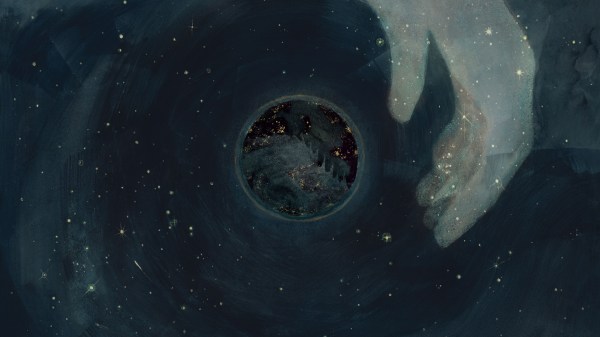

Through God Pops Up, CT Media brings you stories from some of the world’s most dangerous locations. These stories feature people who are risking their lives to share the Good News. Although we have sought credible sources, for security reasons, we cannot cite those sources, show photos of subjects, or name names. In this series, we use animation to tell true narratives that encourage the global church, but we also seek to protect the people behind those narratives. CT Media created these videos as a discipleship tool for both kids and adults. Thank you for watching and sharing these stories.

If God leads, you can give a tax-deductible gift to any of these causes by giving through the National Christian Foundation (NCF). NCF will anonymously pass your gift to the cause you’ve chosen.

To nominate a story or to underwrite a story that shows how God Pops Up, email godpopsup@christianitytoday.com.