After decades of increasing religious freedom, has China swung toward militant atheism? That’s the takeaway of Religious Freedom Institute president Thomas Farr, who recently told Congress that “the assault on religion in China under President Xi Jinping … has justly been called a Second Cultural Revolution,” a nod to the final chaotic decade of Mao Zedong’s rule, when all religion was banned.

The “Administrative Measures for Religious Groups,” which took effect in February this year, put teeth into existing prohibitions against unregistered church gatherings, stipulating stiff fines for participants and those who host such activities. The regulations also double down on Xi’s insistence that religion be “Sinicized,” or made more Chinese. In the case of Christianity, this means severing the church’s Western connections and reinterpreting biblical teachings in order to conform to “socialist values.”

China’s Christians would generally agree that restrictions on the exercise of their faith are increasing under Xi’s repressive policies. But most would also view their country’s church in a much broader context that defies characterizing it purely in political terms.

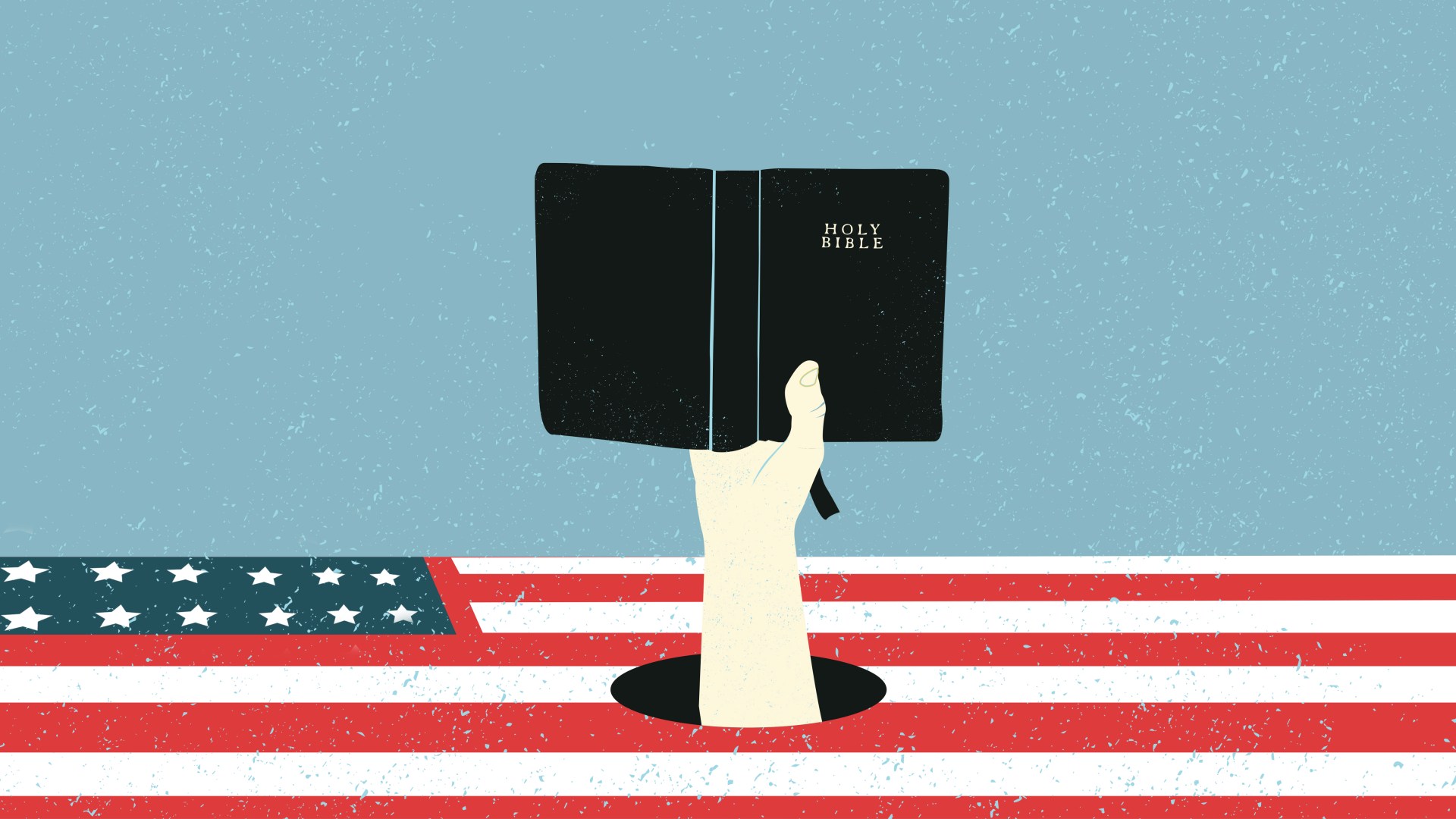

In a similar way, as they acknowledge the reality of China’s repressive religious policies, Christians outside China need to stop seeing Chinese Christians merely as “persecuted.” By putting too much emphasis on politics, the familiar persecuted church narrative keeps Christians outside China from understanding the other dynamics at play in what has become arguably one of the fastest-growing Christian movements in history, accounting for one of the largest concentrations of believers in the world.

Rooted in Western assumptions about the relationship between church and state, this narrative sees the church’s problem as primarily political. It paints believers as innocent victims or—in the case of those who dare to speak out against the regime—as tragic heroes. While based in reality, this narrative does not begin to tell the whole story.

The Stories We Tell About China

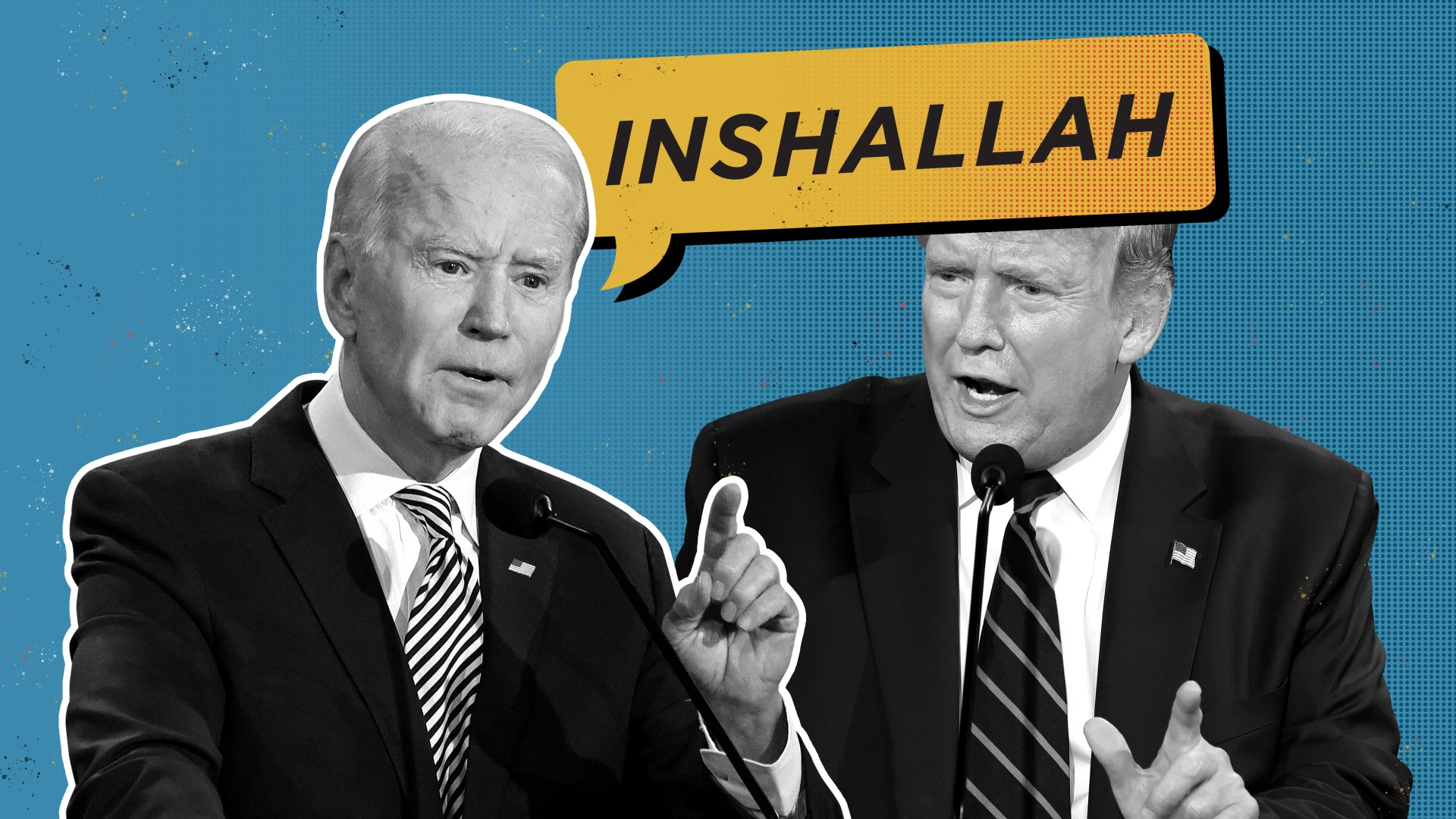

The persecuted church is one of four dominant narratives that have characterized Western and overseas Chinese Christian discourse on China over the past four decades. It remains the go-to storyline for journalists conditioned to look for conflict between the authoritarian state and groups in society that dare oppose it. Rights activists, think tanks, politicians, and many evangelical organizations amplify the story, often to support issues that are tangential to China itself. In this way, China’s persecuted church easily becomes an unwitting prop in the service of others’ agendas, particularly in the rancor of the US election cycle. While the church portrayed by this narrative certainly exists, it is at best a one-dimensional depiction of Christianity in China.

These various narratives contain an element of the truth, but none tell the whole story.

First, the needy church narrative builds on this portrayal of Christians in survival mode, lacking Bibles, trained leaders, and material resources. For foreign Christians who measure their own effectiveness by their ability to help, the church in China becomes a new section in the organizational strategic plan, a pin on the map in the mission agency boardroom, or a line item in a foundation budget.

Though this narrative may have been accurate in the 1980s as China emerged from the dark shadows of the Cultural Revolution, the church of today is much better resourced. Hundreds of locally run training institutions, both official and unofficial, are equipping a new generation of leaders. A vibrant online Christian community conducts worship services, hosts conferences, and shares discipleship resources—all within the bounds of China’s highly regulated internet. Through innovative local nongovernmental organizations and Christian-run enterprises, believers have emerged as salt and light in their communities. Most of these activities require little or no foreign involvement, and in today’s anti-foreign climate, such outside help could be a liability.

The Christian China narrative emphasizes the church’s numeric growth on the premise that a critical mass of believers will bring about cultural and political change. Proponents of this narrative—often found in evangelical educational institutions or student ministries—talk of filling the void left by communism and of reaching China’s future leaders. Ironically, it is exactly this sort of bottom-up transformation that Xi’s repressive policies, which seek to blunt foreign influence in China, are intended to prevent. While it is true that today’s Chinese Christians—like generations of believers before them—have been able to enter the cultural sphere in significant ways, their voices are increasingly being silenced. The resurgence of authoritarian rule under Xi has again shown the limits of Christian engagement in bringing fundamental change to China, at least in the near term.

Finally, the missionary church narrative envisions a mighty wave of gospel messengers—perhaps the largest in history—being sent from China to peoples hitherto unreached. Foreign mission organizations, captivated by the Chinese church’s “Back to Jerusalem” vision and finding it harder to recruit at home, rush to equip this new mission force with the latest strategies.

The Chinese church is in fact developing its own mobilization and sending structures. An estimated 1,000 to 1,500 long-term cross-cultural workers have been successfully deployed to fields outside China. Sadly, many times that number have returned to China disillusioned because of poor or nonexistent preparation, conflicts on the field, cultural challenges, or a lack of support from their home churches. Although these missionaries need more local backing (and even maybe even some strategic support from the West), the fact remains that the church in China is already creating its own missionary force and sending that force out into the field. In other words, the Chinese church doesn’t need Western intervention and leadership in order to be a missional church.

Again, these storylines contain elements of the truth. Yet each is incomplete. At best, they approximate something of the complexities of China’s church. At worst, they become caricatures, distorted pictures that would be largely unrecognizable to those whom they purport to describe. At the end of the day, they are still our narratives. As such, they say as much about us as they do about the church in China.

China’s Magic Mirror

For centuries, the Chinese “magic mirror” proved an object of intense fascination among Western visitors to the Middle Kingdom. Cast of solid bronze, with an intricate design carved on the back, the mirror’s highly polished surface appeared to project this design when exposed to bright sunlight, giving the impression that the mirror was somehow transparent.

Narratives about the church in China function somewhat like this mysterious mirror. While appearing to elucidate the Chinese church, they inevitably become reflections of those who promote them. These narratives reveal their preferences for what China ought to be—a free, open society with well-run, well-resourced churches that impact their society and reach beyond China’s borders. Understandably, those engaged in or with China see China in ways that align with their goals. This often results in viewing China’s church either in terms of its limitations or in terms of what they believe it should be doing. While ostensibly about China, these narratives invariably put those who promote them at the center. Humility and honesty are needed in order to maintain a clear perspective on what is actually happening in China.

Like the engagement myth that has dominated contemporary Western interaction with China, promising that trade will somehow bring about political change, these narratives imagine a linear relationship between foreign Christian involvement and China becoming a different place.

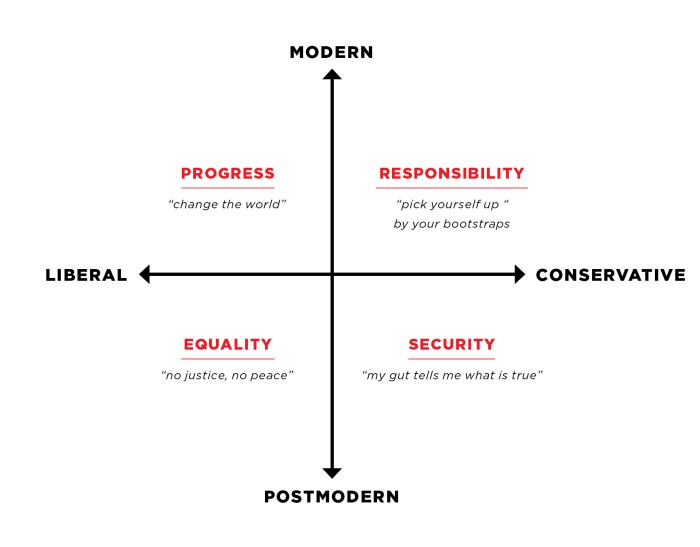

A product of the modern era, these narratives speak of control, of measurable outcomes, transforming institutions, harnessing technology, multiplication, scalability, and finishing the task. In many ways they have dovetailed nicely with China’s own Herculean modernization effort. Yet, as a strong, authoritarian China rises on the world scene, and as the Western church declines in its ability to project its vision upon the rest of the world, the limitations of these narratives become increasingly evident.

Reframing the Conversation

To move toward a new narrative, a new conversation is needed with, and about, the church in China—a conversation that, instead of objectifying the believers, embraces them as true partners in the kingdom. With an estimated 100 million Christians worshipping in unregistered “house” churches or in officially sanctioned congregations under the Three-Self Patriotic Movement, China’s church represents a spectrum of theological traditions. These include indigenous strains whose historical influences include figures such as evangelist John Sung and Little Flock founder Watchman Nee, as well as a growing Reformed movement among newly emerged urban congregations.

Becoming more visible and more influential in recent decades, China’s Christians have broken out of the “surviving church” mold in which they are often cast by outside observers. Even amid current restrictions, they are living out their faith in a manner that would have been unimaginable 15 or 20 years ago. Pastors’ networks spanning the country meet regularly for prayer. Chinese believers are finding creative ways to care for the marginalized, engaging in cross-cultural outreach, and witnessing for Christ online and in the marketplace. As one pastor wrote recently, “The era of new media has given the majority of pastors, churches, and individual Christians the opportunity to enter into the public sphere, and expound their own thoughts and opinions in accordance with the Bible regarding public affairs.”

We need the Chinese church to be defined not by its limitations or what it does, but by how it is being made into the image of Christ. The personal transformation taking place in the lives of Chinese believers is the key to this new narrative.

In this light, the familiar themes of our common narratives don’t go away; they take on new meaning. China’s government is repressive, and its church has many struggles. But within these harsh realities there are new stories to be told and, if we are listening, lessons to be learned that address concerns of Christians globally. In this new narrative, China’s church does not change, but our perception of it does.

Instead of focusing solely on the persecution itself, we join Chinese Christians in their profound recognition of how God meets us in suffering. Their example of grace under oppression speaks volumes to believers around the world who suffer in various ways.

In this new narrative, the emphasis on our ability as Western Christians to meet others’ needs is replaced by a willingness to acknowledge our own needs. We recognize that a church that has experienced some of the most extraordinary growth in history may actually have something to say to believers in countries where church attendance is declining. As China’s urban unregistered church leaders are forced to abandon the American- and Korean-inspired megachurch model, for example, there is an opportunity to learn together how the church can grow in inhospitable environments.

Instead of hoping for more “Christian” institutions to transform the culture, we see how Christians in this new narrative are personally transformed as they become vulnerable to one another and to the Holy Spirit in times of weakness. Like believers in Wuhan at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, they experience the power of Christ working through them to bring about change in ways that don’t require access to mass media or the levers of political power.

Finally, as we find opportunities to partner in God’s global mission, we join Chinese Christians who are learning how to have a redeeming presence in cultures different from their own. Their effectiveness depends not on strategies for projecting resources or influence from one part of the world to another, but on their authentic incarnational witness.

In the era of Xi, as China’s Christians begin writing a new chapter in their own story, it is time for foreign Christians to reconsider their China stories in light of a much larger narrative, one that sees Christ working sovereignly both inside and outside of China to prepare a bride for himself.

Brent Fulton is the author of China’s Urban Christians: A Light that Cannot be Hidden and the founder of ChinaSource, a platform engaging Christians in China together with the global Christian community for research and collaboration to serve China’s church.

Speaking Out is Christianity Today’s guest opinion column and (unlike an editorial) does not necessarily represent the opinion of the publication.