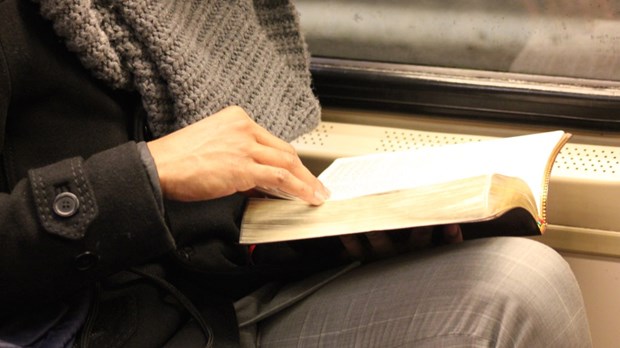

It’s New Year’s resolution time, and for some subset of the population, reading the Bible is one of those things—like weight loss and exercise—that people vow to do more of at the beginning of each year. Countless plans and systems exist to help people try to keep up (as Tim Challies documents here). These plans encourage reading the entire Bible in 365 days (or in some cases, two to three years), start to finish.

I’ve read through the Bible before, and I suspect I will do it again. I consider the Bible the Word of God, inspired by God and authoritative in my life and in our world.

And yet I also wonder about the helpfulness of reading the Bible in its entirety. Plenty of people admit to falling off the wagon, so to speak, when they get to Leviticus (the third book of the Old Testament), and plenty more get tripped up by the warfare and sacrifices throughout, but my concerns about this type of Bible reading go deeper than the practical problems some of our ancient Scriptures pose.

First of all, reading the Bible is not something to check off a bucket list. Sure, broad reading of Scripture can serve a very positive and particular purpose—to provide an overarching sense of God’s work in human life over the centuries and across cultures. But broad reading can also lead to a deceptive sense of accomplishment rather than to an encounter with the Spirit of God who has inspired these writings. “The word of God is living and active” (Hebrews 4:12), and active engagement with that word involves prayerful contemplation, not skimming chapters in order to say we’ve done it.

Still, plenty of people seek to read the Bible as a whole with very good intentions but end up feeling like failures because the time just slipped away or the rites and customs became too convoluted or the words of the prophets too confusing. The second reason not to read the Bible cover to cover is gracious realism. One way to grow in our knowledge and love of God is through God’s word, without a doubt. But God’s grace extends easily to those of us who haven’t memorized any verses lately and who can’t explain the inner workings of Habakkuk.

Third, the Bible was written to be read in community. Of course this intention does not preclude individual reading of Scripture, but it does suggest that community ought to frame our individual reading practices. That might mean reading the Bible cover to cover in some sort of group, but it more likely means a slow progression in conjunction with others.

Finally, although the Bible can (and should) be read as a whole, certain books within it are more accessible and more foundational than others. The story of Jesus anchors Christian Scripture, for instance, and so the gospel narratives can be read again and again to mine the depths of God’s work on our behalf through Jesus. The Psalms have been the prayer book of the Jews and Christians for ages. Repeated and frequent reading of these words has provided an entry point to prayer and communion with God for communities of faith going back millenia.

I don’t mean to suggest that Zephaniah is irrelevant, or that Jude should be excluded from the canon. But I do mean to suggest that the Gospels and the Psalms should come first, and more often, than the less accessible and less foundational stories throughout Scripture. It’s kind of similar to reading documents to understand the Civil Rights Era in American History. Many Americans are familiar with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s I Have a Dream speech from 1963. Most of us have not read the Civil Rights Act passed by Congress in 1964. Each text—the speech and the law—is of great importance in the history of the movement. And yet I suspect most people would start by reading King’s speech to get an emotional and historical grasp on the reality of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960’s. And most people would return to that speech again and again as a reminder of what the law upholds and codifies.

So if you are already familiar with the Bible and you want to read it cover to cover because you want a deeper understanding of God’s work throughout history and in your life, go for it. But if you want to read the Bible cover to cover in order to check it off a list and feel proud of yourself, you might want to set a different goal. And if you are new to the Bible but want to engage these texts that have been foundational for faith and life for billions of people throughout centuries, pick and choose—ideally in community—based upon the texts that tell the foundational story.

If what the Bible tells us is true, God wants us to respect and know his Word. But far more important, God wants us to respect and know and even love Him. The Bible is a means to the end of knowing the Word made flesh. I return to the Gospel of Luke—written nearly two thousand years ago as a simple explanation of Jesus’ life and death—almost every year. I haven’t read Nahum in ages. Perhaps you’ll join me.

Support our work. Subscribe to CT and get one year free.

Recent Posts

Why You Don't Need to Read the Whole Bible

Why You Don't Need to Read the Whole Bible

Why You Don't Need to Read the Whole Bible

Why You Don't Need to Read the Whole Bible