More than one-third of American evangelicals believe that climate change is a pressing problem, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey. One of the groups mobilizing believers on this issue, Young Evangelicals for Climate Action (YECA), celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2022. National organizer and spokesperson Tori Goebel spoke to CT about what has changed in the last decade and how younger Christians are pursing activism as an expression of love and hope.

What was the evangelical conversation about climate change like in 2012 when Young Evangelicals for Climate Action started?

One of the reasons YECA was founded was that climate change was not really being discussed. Remember, 2012 was an election year and climate change wasn’t coming up in the campaigns and the debates.

We also weren’t talking about it in our churches. As an evangelical, I see how climate change activism connects to a core mandate of my faith: to love God and care for our neighbors. So why aren’t churches talking about it? Climate change seemed to be off-limits. But when our churches don’t seem to care that we are impacting our climate in a way that’s going to have a detrimental impact on our neighbors, that’s really frustrating.

So the motivation for starting YECA was to empower young people and equip young people to talk to their churches and have these conversations—start the conversation. We could help the church understand that this is a way to live our values, to care for our neighbors and God’s creation.

How has the conversation changed in the last 10 years?

At the beginning, a lot of the conversations were “What is climate change?” Climate science 101: “Is this even happening and are humans contributing?” We were having those really important but very basic, starter-level discussions.

Now, it has shifted. When I talk to college students and church groups about the theology of creation care and the issues with climate change, the questions are about how to respond, what are good policies to support, and what role can Christians play, bringing their faith to this space. They want to know “What difference can I make? What can my church do?”

The young evangelicals that we talk to are looking for hope and avenues for action.

A recent Pew Research survey said that roughly a third of American evangelicals think that climate change is real and caused by burning fossil fuels, a third believe the climate is warming but disagree with the majority of climate scientists on why, and the rest are divided between “don’t believe” and “unsure.” What do you make of those numbers?

I think what it tells me is that there’s still work to be done, but I’m encouraged that public perception is changing and evangelicals are more open. I feel like we’re headed in the right direction, even if I wish it were quicker.

Tell me a little about how you came to see climate change activism as part of your faith.

I grew up in a wonderful conservative Christian home. We recycled. We explored nature. But we weren’t talking about climate change at home or at church. So I wasn’t aware of the climate crisis until I was at Gordon College. One of the required classes, developed by Dr. Dorothy Boorse, was on energy and the environment. We studied how our lifestyles, here in the United States, involve the extraction and burning of fossil fuel and [how] that was contributing to this global problem.

I never felt like the reality of climate change challenged my faith or created any tension; it just raised questions about how I was supposed to love my neighbor and concerns about the silence of our churches on this issue. The pastors I grew up with talked a lot about mission trips, caring for the poor, making sure our neighbors were taken care of. So climate change didn’t seem different than that to me. But there was a tension with the leaders and their apparent lack of concern in this area.

I think for an older generation of evangelicals, climate science seemed more partisan, and they didn’t trust the science as much or maybe didn’t understand it. That does become an issue for young people. In my experience, the number one reason young people leave the church isn’t hatred of the faith or loss of faith but frustration at perceived and real hypocrisy.

Is the discussion of climate crisis less partisan now than it used to be?

I see more and more bipartisanship: There are solutions that are bipartisan, there are Republicans who care about this, and there is a bipartisan Climate Solutions caucus and conversations across the aisle.

In the past, there were intentional disinformation campaigns around the issue, undermining trust in the science and encouraging people to think it’s all political. That has permeated our churches. A lot of it targeted evangelicals.

There’s also been a fear of solutions that look like they always require bigger government and the loss of freedom. Having a conversation across the aisle, with different people offering different solutions, helps depoliticize the conversation. Anything that contributes to depoliticizing the issue is good, from my perspective.

What are the big accomplishments YECA is celebrating at 10 years?

The growth in our college fellows program is a huge success. We’ve had 90 fellows from 40 different colleges and universities.

We’re really proud of our involvement in the policy landscape. In 2015, we had a letter-writing campaign to denominational leaders and the National Association of Evangelicals, which helped lead to the NAE adopting a statement on creation care and climate action. In 2016, YECA hosted prayer rallies at every Republican presidential debate and interacted with the candidates, letting them know there are Christians who care about the climate. In 2019, YECA was invited to testify before Congress, and we’ve worked a lot in the last year and a half on infrastructure and climate issues in the Build Back Better legislation.

We also look back at our presence at UN climate conferences. We help run the Christian Climate Observers Program there, which is a leadership development program that serves young people around the world, helping to develop a new generation of leaders on the national stage.

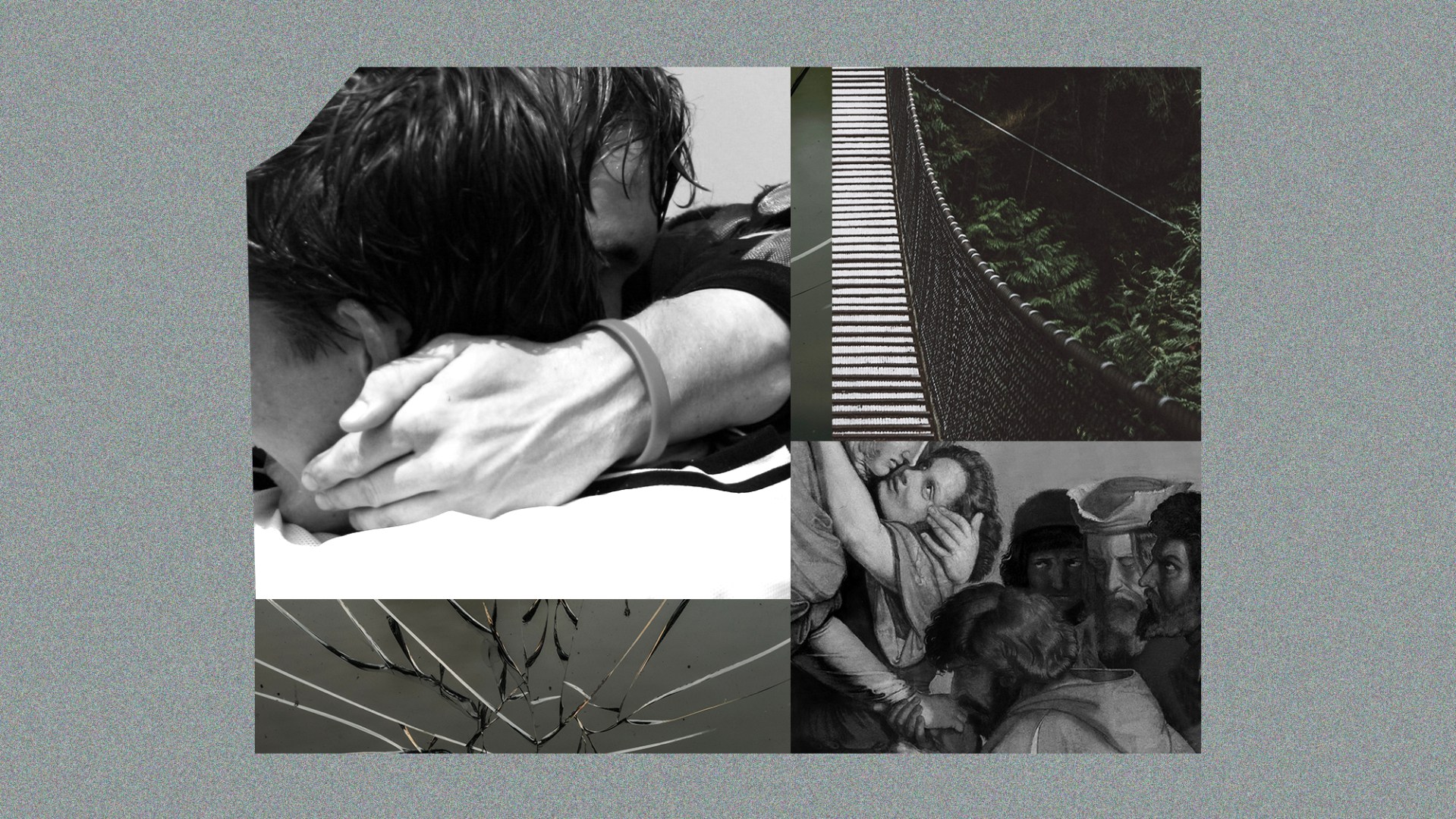

A lot of climate activists talk about being overwhelmed by despair. How do Christian activists deal with that?

Eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-grief are all too real. I’m not immune to it, and neither are the young people we work with. I feel anxious about the future. I feel discouraged by the lack of action. I think that’s what makes it important for YECA to talk about.

But we can learn to hold despair in tension with hope, feeling this overwhelming sense of fear about the severity of the problem but also understanding that hope is important to taking action and combating that fear. I think that’s where, as a Christian organization, we bring something unique to the movement. We have a unique sense of hope and purpose. We understand this as part of our faith, part of our identity as followers of Christ.

We try to name it and create space for self-care and to pray for it, pray about it, and pour into our communities. And we remember that action can be a form of hope.