I lay alone in the hospital bed with searing pain coursing through my body. For three months, I had been unable to stand or sit for longer than 30 minutes. The doctors had no solutions for my constant nerve pain and debilitating muscle spasms. In my agony, I wondered if my calling to Christian teaching and scholarship had run its course.

Before the pain started, I had been a fairly healthy and successful professor at Baylor University. I had published multiple books, completed work on a significant grant, and enjoyed class discussions with PhD students in a program I helped build. In March 2017, I went in for what I assumed was a routine medical procedure. Shortly afterward, I was in anguish.

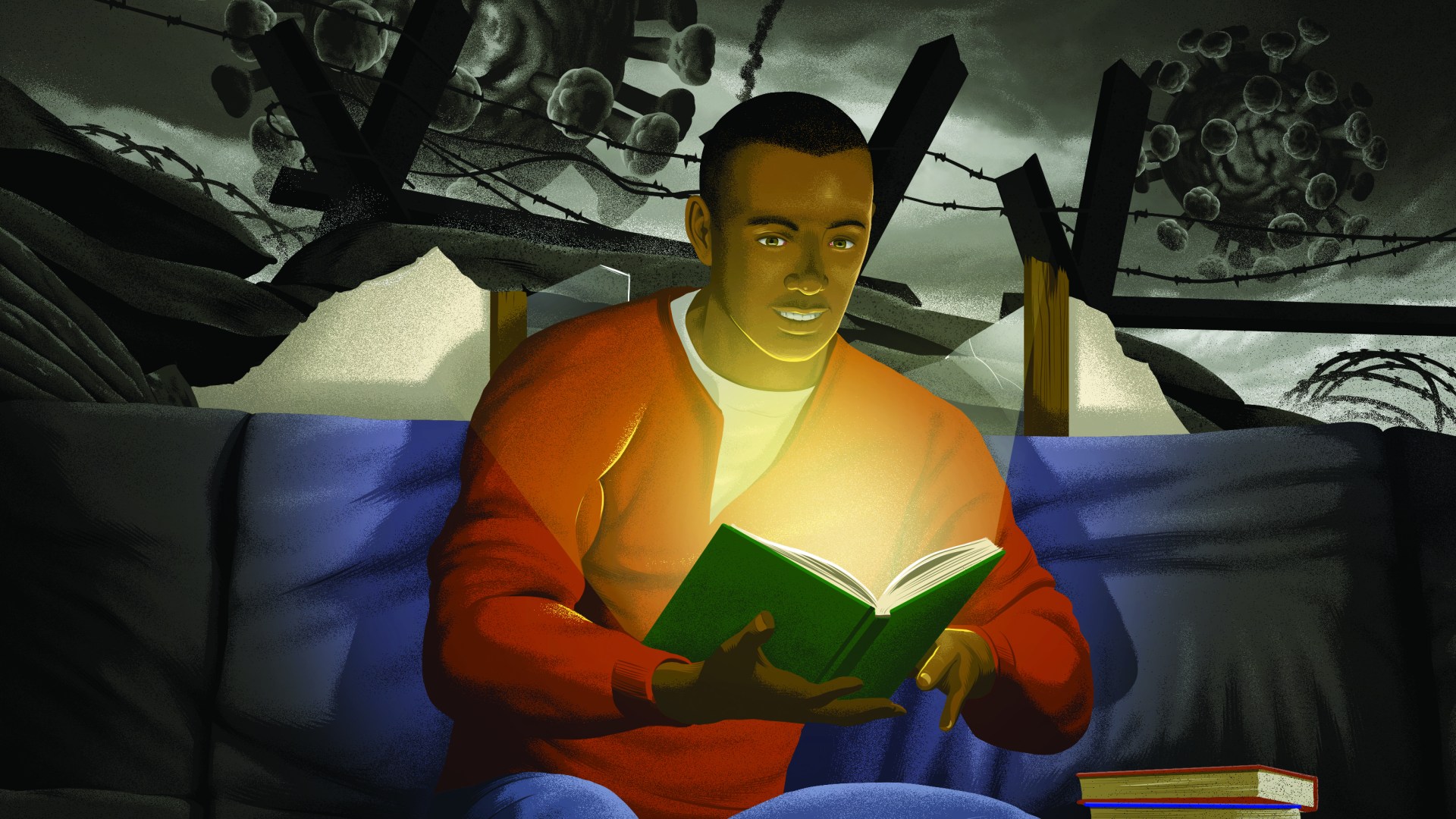

I became a prisoner to pain. To keep it under control, I had to languish in bed. I could no longer go to work, exercise, drive, or sit at the table with my family for evening meals. I felt isolated from friends and church.

Nor could I fulfill the basic responsibilities of being a professor. During most of those months, I did not even feel up to reading, much less writing. In my Job-like pity party, I felt as if anything that had given me fulfillment or a sense of identity had suddenly been taken away. “Who am I, now that I seem to have lost everything?” I wondered. Would I ever be able to teach, write, and learn in the same way again?

In all likelihood, the fallout from COVID-19 has led some educators and students to ask similar questions. Perhaps you (or your loved ones) have contracted the virus and dealt with long-term complications. Perhaps your life arrangements have been upended because of online learning, lockdown restrictions, or the economic fallout. Crises always raise questions about who we are and what God has called us to do. I hope to remind us of the reasons for our calling to learn—and to address the barriers and distractions that crises tend to throw in our way.

Prayer Must Take Over

“I don’t want to die,” my youngest son said while discussing COVID-19 one night at the dinner table. He is 16 and has a compromised immune system, as does my wife. My other son used to have asthma. I also have 81-year-old parents, one of whom has a partial lung. Everyone I love seems vulnerable.

I know my experience is not unique. We all fear losing people we love. The specter of death haunts us. We may lose sight of the calling we have received from God. What do we do when the fear of death distracts us from that calling?

First, we must pray. When my wife told me she wasn’t feeling well a few months ago, I faced an onslaught of paralyzing fear. Was it COVID-19? When fear threatens to take over our lives, prayer must take over instead. We pray to align our hearts with God’s heart. Through prayer, he comforts and guides us, reminding us of who he is and who we are.

What does prayer look like during times of crisis? There are any number of forms it can take. My brother-in-law, who lives with unforgiving chronic pain, taught me that sometimes you just pray, “Lord, help me live this next hour well” or “Lord, help me live this next five minutes well.” Other times, prayer is more colorful. During my health problems, many of my prayers involved little more than yelling at God. If you have yelled at God recently, that’s good. It means you are still living in relationship with him, even amid extreme stress. Furthermore, as the Psalms remind us, God can take it. In fact, God is the only one who can carry the burden of our fear.

Yet the Psalms also give us something more. During my hospital stay, some old university friends came from Virginia to visit, which proved providential. They prayed for me and lifted my spirits. Later, one sent me a book of Psalms. Of course, I already had a Bible, but for some reason, that separate book of Psalms got me reading, praying, and memorizing them more.

Through those three practices, I remembered to live in God’s story. I gained words to express my anguish in the laments: “I am worn out calling for help; my throat is parched” (Ps. 69:3). I breathed in hope-filled longings: “Lord, I wait for you; you will answer, Lord my God” (Ps. 38:15). And I was reminded: “The Lord is close to the brokenhearted and saves those who are crushed in spirit” (Ps. 34:18).

Remember the First Great Commission

Once we deal with our emotional paralysis and immerse ourselves again in communion with God, we can refocus on fulfilling our calling within God’s story. C. S. Lewis’s sermon “Learning in War-Time,” delivered at the beginning of World War II, reminds us that humans are always facing down the reality of death and eternal judgment. Lewis invites Christian students to ask themselves, “How [is it] right, or even psychologically possible, for creatures who are every moment advancing either to heaven or to hell, to spend any fraction of the little time allowed them in this world on such comparative trivialities as literature or art, mathematics, or biology”?

In my first year of college, I pondered similar questions, and I started answering them in a way that interfered with my call to learn. In my mind, simple evangelism and discipleship (as I narrowly conceived them) took precedence over political science and economics. I found myself convicted by the same pointed question Lewis asked his audience: “How can you be so frivolous and selfish as to think about anything but the salvation of human souls?”

It took me two years of college to understand what Lewis’s essay illuminated in a few paragraphs. You cannot live your whole life with a battlefront mentality. As Lewis noted, even frontline soldiers in World War I rarely talked about the war. Instead they spent most of their time doing normal activities, including reading and writing.

The war against COVID-19 has not changed that reality. Certainly, we spend more time hand washing, social distancing, and telecommuting, but we still spend the bulk of it on everyday activities like eating, relating, working, and learning. Our classes, meetings, church services, and hangouts with friends happen virtually or at a distance, but they happen all the same. As Lewis told his faculty and student audience, if you suspend all your intellectual and aesthetic activity in a crisis, “you would only succeed in substituting a worse cultural life for a better.” We still face decisions about whether to binge Netflix, study for classes, or cultivate deep relationships with friends and family—if only online or six feet apart.

To put it in theological language, even during crisis times, we should not neglect God’s first great commission (filling and cultivating the earth) just because his second great commission (making disciples) remains binding.

Genesis 1 contains an amazing statement about humans and their calling: “Then God said, ‘Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.’ So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” (vv. 26–27).

God creates. Since humans are made in his image, we are also designed to create. Indeed, God in his first great commission calls humans to be “fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it” (Gen. 1:28). We are given the honor of creating culture. We make tools, write music, and even build cities (actions described in the fourth chapter of Genesis). We construct whole civilizations with roads and bridges, with languages and books. We launch businesses and charities, found hospitals and universities, and establish art galleries and theaters.

In all these endeavors, God made us to seek after him and to know his thoughts and character. He designed us to desire truth, goodness, and beauty and to discover his wisdom (Prov. 1, 8). As the 12th-century educator Hugh of St. Victor reminds us, pursuing wisdom means encountering the living mind of God, as if one were entering “a friendship with that Divinity.”

This is why we learn—not just to get money or a job, although these are important. We learn because God made us in his image so that we might reflect his creativity, truth, goodness, and beauty. We also learn to recover the fullness of that image, joining with Christ to reverse the effects of the Fall on both our individual lives and the world as a whole. Indeed, Christians have populated the world with schools in part to advance these very goals.

The pandemic has only amplified this point. If epidemiologists, scientists, and health care workers had ignored God’s call to study in college, they would not be prepared to fight the virus. We need economists to help us navigate financial pitfalls. We need psychologists, poets, writers, philosophers, and artists to help us process the mixed emotions we feel. We need pastors, worship leaders, and theologically equipped laypeople to help us see the pandemic in light of God’s larger story.

Within this perspective, Christians should be the biggest fans of learning. Confronting a crisis always requires God’s wisdom, which we find in Scripture and in the best of human tradition. In contrast, as Proverbs repeatedly says, only fools despise wisdom, instruction, and understanding. We wage war against the current pandemic by pursuing knowledge and wielding it skillfully. Surely our health care workers and medical researchers should avail themselves of all the gifts that human ingenuity and God’s grace can supply.

Perhaps you have been uncertain whether to pursue or put off learning during this time. If you really love it and hear its call for you (Prov. 1:20–33), you must pursue it now rather than wait until things get “back to normal.” As Lewis describes the greatest human learners: “They wanted knowledge and beauty now, and would not wait for the suitable moment that never came.”

New Forms of Discipline

We should not be surprised if the pandemic has interrupted the work of teaching and learning. Major crises tend to do that. Still, we have to guard against letting adverse circumstances consume and exhaust us.

Obsessive fear can be a major deterrent to staying the course. Does anxiety take over your life, occupying every waking thought? I can attest to this danger. When I first ran into major health problems, I let them dominate everything. I spent hours searching for answers online. I slipped into depression from the pain and mental exhaustion.

As I gave myself over to such vain pursuits, my wife shared some badly needed wisdom. A decade earlier, when she spent a year in bed recovering from her own medical issues, she had learned about dealing with conditions of enforced “quarantine.” The Lord slowly taught her the importance of structuring her day. She reminded me to begin the day spending time with God and doing the stretches and exercises that helped me calm misfiring muscles and refocus a wandering mind. Gradually, I relearned to steward my body, mind, and soul.

To learn well during a pandemic, we have to establish new structures and rhythms that keep the pressures of the moment from overwhelming us. While remaining committed to the God-ordained tasks at hand, we might need to experiment with unorthodox means of completing them.

During my bout of severe pain, I could no longer sit or stand for extended periods. To keep writing, I had to think creatively and learn to use some new tools. I ordered a computer stand that allowed me to write while lying in bed. By God’s grace, I soon found that focusing on work distracted me from the pain and helped restore my earlier productivity. In fact, I wrote two of my books in this manner.

Just as being confined to bed forced me to write in new ways, COVID-19 has forced us to teach and learn in new ways. Having taught both online and in person, I have no doubt that teaching in person is more conducive to learning. Students attending class online are easily distracted by their phones and their surroundings, including pets, other family members, and snacks in the kitchen. Maintaining focus requires a new form of discipline.

What can help us attain it? First, we treat online learning, just like in-person learning, as an essential part of God’s calling on our lives. Second, we treat it as a spiritual discipline that furthers sanctification. Listening to people closely is a skill of love. Online learning obliges us to practice this virtue in a challenging context. Third, we exercise moral agency. This involves staying mentally focused and avoiding the temptation to multitask. (In other words, get off your phone!) Online learning is no excuse for half-hearted effort. As Lewis argued in Mere Christianity, “God is no fonder of intellectual slackers than He is of any other slacker.”

And finally, we reward ourselves with Sabbath rest and play. If we feel we have to work seven days a week during the pandemic, we are likely trusting our own strength more than God. If we feel we need to skip communing with God to survive, we are failing to trust God with our time.

The COVID-19 crisis merely confirms what Christians should already know: Ever since the Fall, life has never been “normal,” and the days have always been unnaturally evil (Eph. 5:16). Satan, this world, and our sinful flesh continually conspire to distract us from God’s call on our lives. Yet his grace still empowers faithful Christians—inside and outside of classrooms—to seek God’s companionship, to know his mind and designs, and to accomplish his purposes in this world.

Perry L. Glanzer is professor of educational foundations at Baylor University, where he is also a resident scholar with the Institute for Studies of Religion. He is coauthor of The Outrageous Idea of Christian Teaching and Christ-Enlivened Student Affairs: A Guide to Christian Thinking and Practice in the Field.