About 70 years ago, a handful of people with leprosy and a blind man shared the gospel with the Kamwe people in northeastern Nigeria, and many in the community accepted Jesus. Today, up to 95 percent of the Kamwe profess to be Christians. This year, 30,000 copies of the entire Bible are being printed for the first time in their native language.

Christianity Today interviewed Bible translators Roger Mohrlang, an American who spent 38 years as a theology professor at Whitworth University and oversaw the translation work, and Mark Zira Dlyavaghi, a Nigerian who was the primary translator and team coordinator for the project. They shared why they got involved, how they persevered, and how their translation efforts might shape the rest of Nigeria.

Why and how did you decide to get into this work originally?

Roger: It all began with my conversion to Christ during my college years. I was a physics student at what is now Carnegie Mellon University. I had an engineering professor who asked me one day, “Are you a Christian?” He was the one who encouraged me to use my college years to get into Scripture. I spent endless hours reading, studying, memorizing Scripture, and that, more than anything else, changed my whole life.

I realized my life was not going to be centered on physics. What can I do that would be significant in the work of Christ? I didn’t see myself as a pastor or an evangelist, but I was drawn to Bible translation, in large part because of the effect that reading Scripture had had on my own life.

Mark Zira: I went to a missionary school that was close to my village. One of the lepers was in my village, teaching God’s Word. He opened the primary school there. He started it as a ‘Christian Religious Instruction’ class. I became a follower of Christ in 1975.

Because of God’s call, I went to Bible school in 1988 and graduated with a divinity degree in 1992. When I came home, the Kamwe Bible Translation Committee invited me to join the committee as the first graduate.

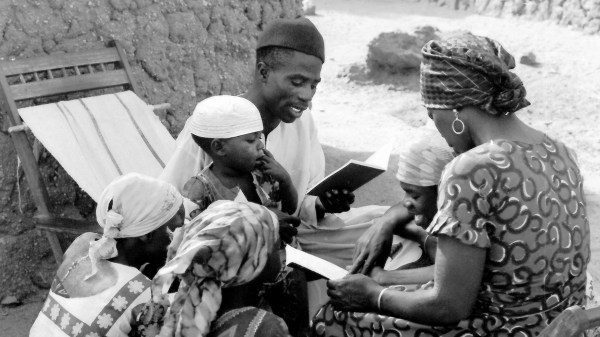

Courtesy of Jean-Paul Becker

Courtesy of Jean-Paul BeckerCan you share a brief timeline of the translation project since it first began?

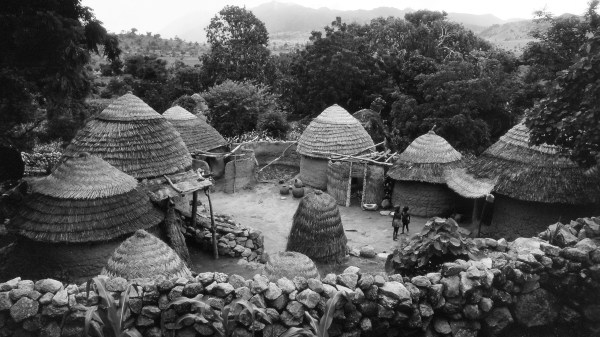

Roger: I arrived in that village, Michika, in northeastern Nigeria in 1968. My job as a missionary linguist was to learn the language, analyze the language, form an alphabet, and produce some basic literacy materials, and especially to work with the Christians on the translation of the New Testament. I left in 1974. The New Testament was dedicated in January 1, 1976, with a huge celebration.

For years, I didn’t hear anything at all from them. I was away doing graduate study and continuing teaching. Then in the late 1980s, I got this letter saying, “All 5,000 copies are sold out. We want another 10,000.” And I was euphoric. A colleague reminded me it’s time to get it onto the computer. All of that up to that time was by pencil and typewriter. So, volunteers in England spent 1,000 hours keyboarding the whole thing, and then I proofread it. I realized we could do better, and that led to a revision project that I coordinated while I was teaching at Whitworth. The revised New Testament was dedicated in 1997.

Ten years later, I heard that they were beginning work on the Old Testament, that they wanted the whole Bible in their language. The last 30 years of work has been done together with the Kamwe Bible Translation Committee. They have done the whole first draft of the Old Testament. I served as a consultant checker. It’s really been their project. A second New Testament revision and the translation of the Old Testament were completed in 2021, and the Kamwe Bible is being printed in Korea.

How do you feel having finished such a lifelong project? And how has this project changed you personally or spiritually?

Roger: I feel relief, joy, and gratitude. One of the things I’m doing right now is writing about stories in my life and God’s hand in it. It’s just been wonderful to see all the good gifts of God and the way that made all of this possible. Part of the gratitude is the fact that my eyes have held out right to the end. I have macular degeneration. That has slowly decreased my vision.

How has it changed me? It’s given me a more comprehensive grasp of the Bible as a whole and of its complexity. My hope and my belief is that spending so much time in all of these words is that these words will be written more deeply in my heart, that I would become more and more the person that God wants me to be.

Mark Zira: I’m overjoyed now because the work is now over. We’re relieved after years of sitting, working, traveling.

I read the Bible over and over and over again, particularly the Old Testament. That has given me a lot in my life and my perspective. I will continue to invest in God’s work until I die.

Have you had moments where you wanted to quit? And if so, what refreshed your spiritual joy to press on despite obstacles and difficulties?

Roger: I don’t think I ever had any desire to quit. What sustained me were two things. One was a sense of commitment to the Kamwe. I thought of it like a marriage commitment. You don’t break that vow, you honor it. Along with that, there’s a sense of calling. I realized I am the one person that knows these languages, the culture, the world of Bible translation. So in some ways, I would be the obvious person to assist with all of this.

Mark Zira: It’s God’s work, so there are enemies attacking from here and there, even within. Sometimes when I remembered those who were attacking me, I remembered others who were supporting me, encouraging and praying for me, and that gave me courage.

Courtesy of Jean-Paul Becker

Courtesy of Jean-Paul BeckerI understand the Kamwe people experienced a community conversion. What do you think were the primary catalysts for this?

Roger: The New Testament in their own language was inevitably one key factor. It meant that when they have church services, they can read the New Testament in their own language. It gives them a sense of identity too.

But the movement toward community conversion was there—the beginnings of it—even before the Bible translation. From a human point of view, that is due to the fact that the earliest evangelists were all Kamwe themselves. This handful of lepers, this blind person, came back from the leprosy clinic, as believers, and as evangelists. It was not an outsider-driven project. There was quite a warm welcome to it. As a result of that, the Christian songs that evolved were all in their local language. Customs were indigenous customs.

The mission in the larger area was the mission of the Church of the Brethren. The fact that the mission brought in medicine, small clinics, and helped to establish schools in the area, was viewed positively.

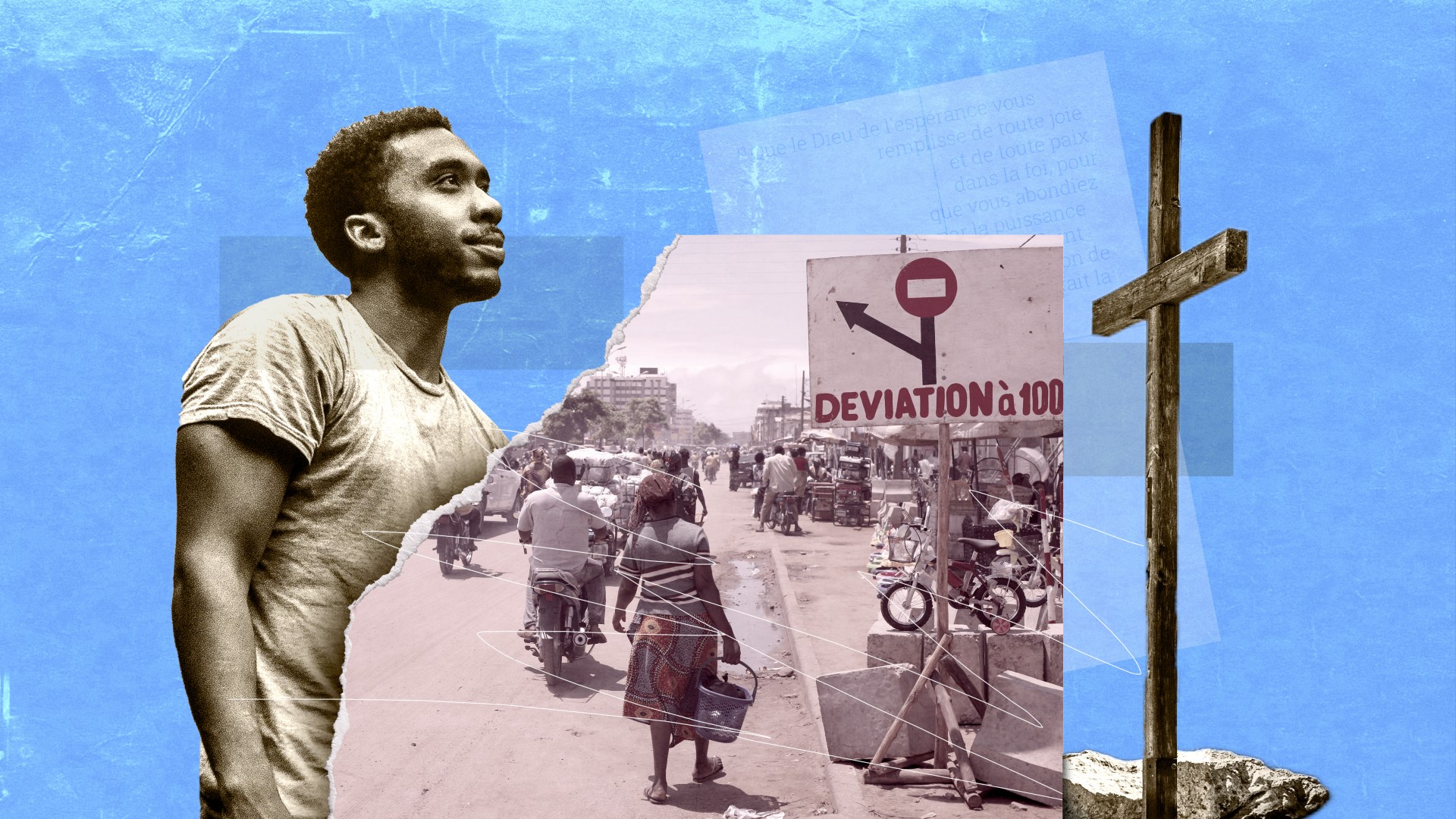

The dominant factor is the grace of God, God doing a wonderful work, orchestrating all of it. It’s the work of the Lord that changes hearts. The fact that three quarters of a million people, up to 95 percent of whom now confess to be Christian, calling themselves a Christian community, right within miles of this jihadist movement to the north, the Boko Haram, is a phenomenal thing.

What was their belief system was before converting to Christianity? And what else can you tell me about the lepers who first brought the gospel there?

Roger: It’s traditional sub-Saharan African animism, belief in the spirit world. They believed in a high God.

Mark Zira: I knew most of the lepers. One was my teacher in the primary school. They had leprosy, so they heard of missionaries who came from America. The Brethren established a clinic 100 kilometers from our village. The lepers went there, were healed of their leprosy, and heard of the gospel. So, when they came home, they went to villages, teaching them about Christ. That’s how most of them received Christ.

Roger: One leper named Daniel became quite a highly respected pastor in the whole area. And I got to know one of the lepers who was a Christian leader in his own village. His name was David. When he was away at the leprosy clinic, he learned how to read and came back with a Hausa Bible. And at the end of the day, when they’d all come in from their farming, he would tell them stories from the Bible and pray for them. He was known as a singer, and he composed Kamwe Christian songs.

How did the Boko Haram attack of Michika in 2014 affect the Kamwe community? And what’s the current and potential future political situation like there?

Mark Zira: The Kamwe community was badly affected. I was part of the tragedy. We were in church on Sunday, the seventh of September, when they were approaching our village. All of a sudden, we heard gunshots everywhere. We were sent out by force into villages, into bushes, and most of us went to other places. It was very, very terrible.

At that time, I had a wife and five children of my own with foster children also. All of us were chased out. We had a car that we took to a certain village, and later they burned it down. They even burned some of my property.

Roger: There are three terrorist threats in northern Nigeria. One is Boko Haram and its rival faction, ISWAP (Islamic State—West Africa Province), both of which are fighting to establish an Islamic caliphate in northeastern Nigeria. In the last 20 years, Boko Haram, with its hideout only 35 to 40 miles north of the Kamwe, has killed tens of thousands of people and displaced an estimated 2.3 million people.

Second is the threat of the Fulani cattle herders who are killing Christians and taking over their land in central Nigeria. In the last few years, they’ve killed thousands of Christians and displaced hundreds of thousands.

Third is the growing number of gangs who are kidnapping people, including more than 1,000 students last year, for ransom in central and northwestern Nigeria.

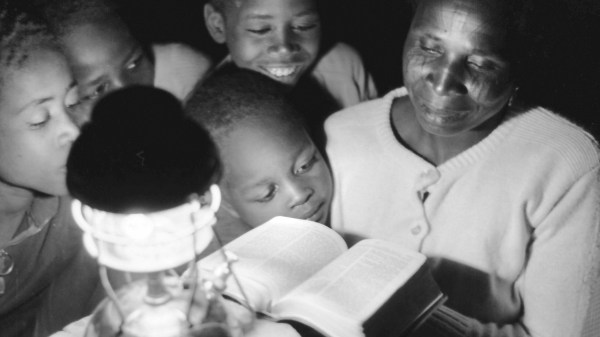

Courtesy of Jean-Paul Becker

Courtesy of Jean-Paul BeckerWhat do you see as the further impact of having the Old Testament completed?

Roger: It would be a wonderful boost for them to be able to read those stories in their own language, preach them from their own language. It will greatly enrich their services.

My hunch is it’s going to increase the songs. The women have been very good at teaching the Christian message by singing. They get a group of women together and one of them is a leader. The leader gets a line. Then everybody responds. That’s the way that they have passed along the Christian message and Christian teaching.

In doing Bible translation work, there’s often no immediate payback. You’re working for 20 years, 40 years, 60 years down the future. It’ll be interesting 60 years from now to see what effects it’ll have.

Mark Zira: When we have a Bible, it is keeping the language going. Many young people do not use the language much. That will encourage them to study God’s Word in their own language and know what God expects of them. When we read it in the church and our homes, that will really encourage us. Everybody is expecting it. The pastors are really eager, asking when the Old Testament will come.

It takes many people from outside helping us, so we are encouraged. We also pray for them that God will bless them so that they will encourage other people like us. I also want to thank Roger who came here as a youth and spent all of his life helping us.

What’s your hope and prayer for the future of the Kamwe Christian community?

Roger: My hope is that the Bible in their language could strengthen every believer, strengthen the church as a whole, and strengthen their witness to the outside world.

Mark Zira: I am praying that the Kamwe are more united, that they will also keep the faith and use God’s Word day in and day out, so that they can be stronger to resist whatever enemies they are experiencing and be able to face whatever trial and temptation is to come.