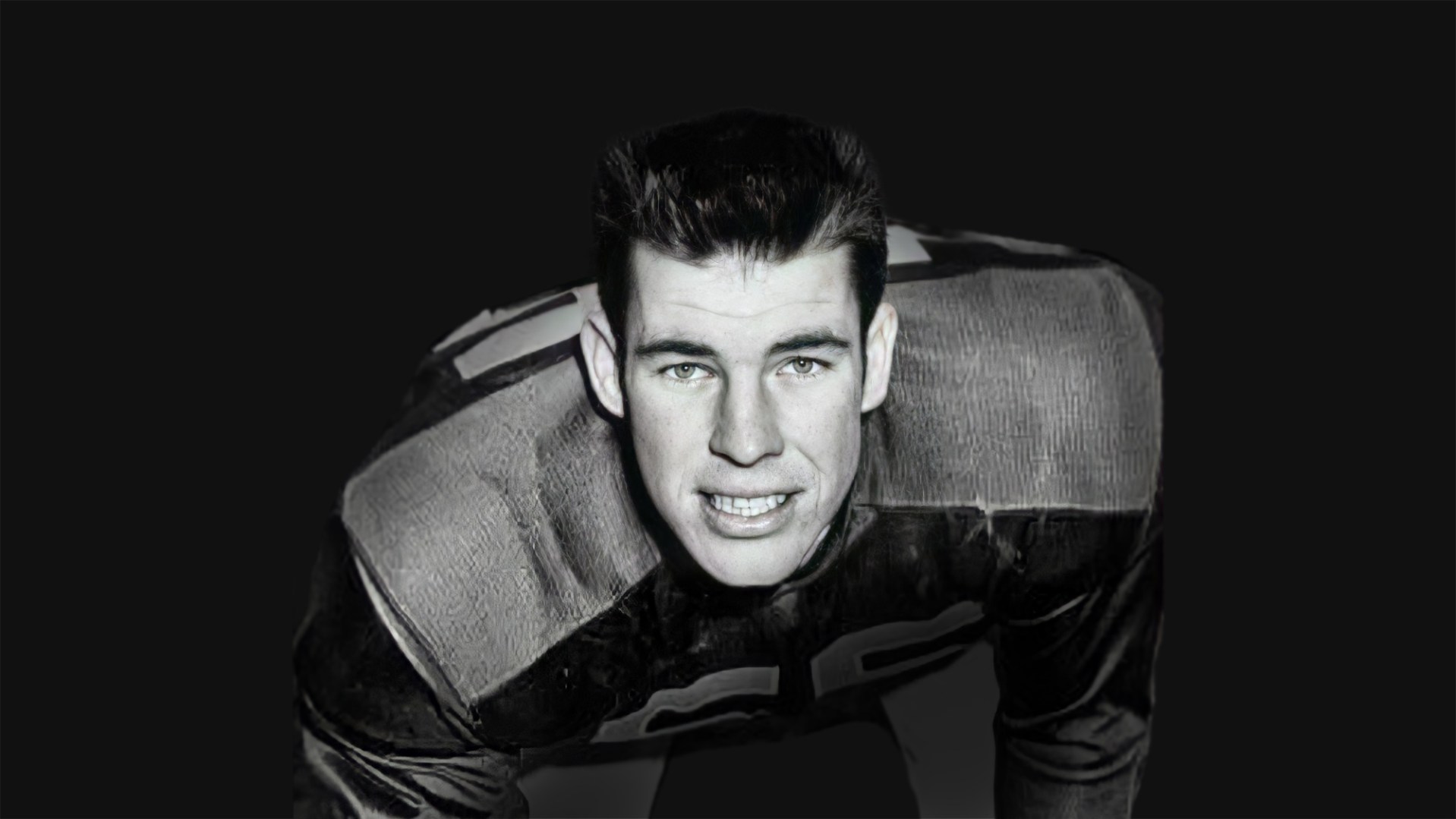

Bill Glass, a football player turned evangelist who pioneered evangelical sports ministry and prison ministry, died on December 5 at age 86.

The six-foot-five, 250-pound defensive end had an impressive resume in professional football, with four Pro Bowl selections, a National Football League championship, and the Cleveland Browns team record for career sacks. But Glass would have pointed to a different set of metrics as far more consequential: In 2019, his evangelistic prison ministry, Bill Glass Behind The Walls, reported that up to that year in their ministry’s history, they had “trained 58,550 Christians to share their faith, reaching 6,056,432 incarcerated men, women and youth, with over 1.2 million commitments to Jesus recorded.”

Glass could also point to the chapel services held before NFL, Major League Baseball, and National Basketball Association games. Evangelical outreach to professional athletes, and the work of organizations such as Baseball Chapel and Pro Athletes Outreach, exists in no small part because of Glass.

Glass brought fans to their feet as a star defensive end, but it was through his pioneering ministry work that his imprint on evangelicalism is most apparent today. When Glass was born in 1935, sports ministry and prison ministry were not a major focus for evangelicals. Glass helped change that.

“His passion for evangelism, training the church in evangelism, and reaching the incarcerated with the gospel was unprecedented,” said Karen Swanson, director of the Correctional Ministries Institute at Wheaton College. “His legacy lives on in the countless lives he touched.”

And Glass “personified a reengaged combination of faith and athleticism conducive to institutionalization,” according to historians Tony Ladd and James Mathisen. “He provided an early model for ministry among athletes that his fellow evangelical muscular Christians would soon perfect.”

Finding confidence in football

Born in Texarkana, Texas, Glass moved with his family to Corpus Christi when he was five. It was there, at 14, that his father died of cancer. That loss would shape his future ministry efforts, which often focused on the importance of father figures.

An awkward, clumsy kid at the time, Glass developed confidence as he poured himself into football, inspired by his high school football coach, a man who became like a second father. It was in high school, too, that Glass had a born-again conversion at his local Baptist church. Faith and football would be central to his life from then on.

Glass enrolled at Baylor University in 1953, where his talent, work ethic, and size opened up future possibilities in the sport. Baylor also brought Glass and his wife, Mavis, together. She was drawn to Glass after reading a newspaper story about a football player who taught a Sunday school class. The two clicked immediately and were married six months after first meeting. They spent 60 years together—Mavis passed away in 2017—and raised three children.

Baylor set the trajectory of Glass’s life in one more way: It introduced him to a brand-new organization formed by a basketball coach in Oklahoma: the Fellowship of Christian Athletes (FCA). Over the next two decades, the FCA galvanized a growing network of evangelical athletes within sports, and Glass was a key player in its rise.

Glass’s identification with the emerging Christian athlete community came at a transitional time for evangelical engagement with professional sports. While Catholic and mainline Protestant athletes were willing to play on Sundays, evangelicals saw this as a clear violation of the Fourth Commandment. As late as 1960, CT lambasted Christian athletes who played professional football and thereby “yielded to the lure of money and added fame, and joined in the desecration of the Lord’s Day.”

At first Glass followed this line of thinking. After graduating in 1957, All-American honors in tow, he spurned the Detroit Lions, who had drafted him in the first round, and chose to play in the Canadian Football League (CFL). But one year later, Glass had a change of heart. Turning away from what he described as his “legalistic” perspective, he decided he would play in the NFL after all.

Witnessing to atheletes

“I just couldn’t believe,” Glass later wrote , “that God was willing for all pro sports to go without a witness just because of Sunday game days.” To equip himself for the work of witnessing, he enrolled at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, spending six off-seasons taking classes before graduating in 1963.

With the Lions, Glass started a practice that would follow him throughout his NFL career: holding Bible study and prayer meetings at the team hotel before games. It began as a one-on-one session with Detroit sportswriter Watson Spoelstra, who later founded Baseball Chapel. Although twice as old as Glass, Spoelstra—who had recently experienced a dramatic conversion—gravitated toward the young defensive end, seeing him as a spiritual mentor.

When Glass was traded to the Cleveland Browns in 1962, he became more intentional and strategic. Along with pregame devotionals, he launched a team Bible study with a simple format: Players would read a chapter of the New Testament together and then rewrite the chapter in their own words, using contemporary language.

Glass’s intense drive to excel and grow earned the respect of teammates, even those who did not share his faith commitments. Bernie Parrish, who played with Glass in the early 1960s, described him as “a kind of paradox, a fundamentalist preacher off the field but a lusty, physical man” who “laughed at himself as well as anyone.”

Glass also inspired an entrepreneurial Florida minister named Ira Lee “Doc” Eshleman. In 1964, Glass invited Eshleman to join a devotional service before a game against the Philadelphia Eagles. “It was heartwarming,” Eshleman said at the time. “I was amazed to think there were that many on one pro team who would place such emphasis on the importance of prayer.”

Two years later Eshleman launched a new career as a self-described pro football chaplain, organizing pre-game services in the NFL. Pro Athletes Outreach, the leading evangelical ministry in pro sports today, began as an offshoot from Eshleman’s ministry in 1971.

Concerns about racial injustice

As Glass became a leading voice for Christian athletes, he occasionally spoke up about issues of moral concern in American society, including racial discrimination. In his first book, Get in the Game! (1965), Glass urged fellow white Southerners to support racial integration. His approach to race followed that of many other white evangelicals. He was not involved with the civil rights movement, focusing instead on person-by-person change and colorblind rhetoric: “Forget color and treat everyone alike,” Glass urged.

Yet Glass also demonstrated sensitivity to the continued reality of racial injustice. His admiration for Cleveland teammate Jim Brown—an outspoken advocate for civil rights—played a role in this.

“Even if a black athlete is treated fairly by the coaches, he still has to live in a prejudiced society,” Glass admitted.

He saw housing discrimination and other forms of inequality as evidence that Black people could be “accepted as a black athlete but rejected as a black human being.”

Ultimately, however, Glass saw himself as an evangelist in the style of Billy Graham, and he took steps toward that path even as he spent his fall Sundays crashing into quarterbacks. Throughout the 1960s, Glass filled his off-seasons with speaking engagements at evangelistic rallies and events. He also began to write, publishing Get in the Game!, the first of more than a dozen books, in 1965.

“I don’t fancy myself as being any great scholar or certainly not a great writer,” he later said. “But I do think you’ve got to write down what you do or otherwise it won’t last.”

Most of Glass’s books were practical guides to Christian living, combining a basic evangelical perspective on sin and salvation with a focus on success and positive thinking. But Don’t Blame The Game: An Answer to Super Star Swingers and a Look at What’s Right with Sports (1971), cowritten with seminary professor William Pinson, Jr., took a different approach. Written as a conservative defense of the social value of sports, it challenged recent books by athletes like Joe Namath and Dave Meggyesy that glorified promiscuous sexual behavior (Namath) or blasted professional football for fostering militarization and dehumanization (Meggyesy).

Glass positioned himself and fellow Christian athletes as constructive defenders of the status quo. Yet Glass later came to wish he had been more circumspect. He especially regretted singling out individual athletes like Joe Namath. “I was picking up stones and throwing them at Namath and all the sinners,” he said last year. “I think I would have had a better witness to him if I just quietly went about witnessing behind the scenes.”

Going into prisons

Glass retired from football after the 1968 season and founded the Bill Glass Evangelistic Association to support his new career as a preacher of the gospel. His evangelistic events were modeled after Billy Graham’s popular “crusades.” In 1972, at the behest of a friend, Christian businessman Gordon Heffern, Glass held his first event inside a prison.

Initially his interest in prisons was limited, but when the Marion, Ohio, prison event proved successful, Glass began thinking about new possibilities for ministry to incarcerated people, gradually adding more prisons to his national crusade itinerary. A few years later, Glass moved to full-time prison evangelistic work, part of a larger “prison revival” taking place in the 1970s, where evangelical ministries innovated new forms of correctional outreach.

Glass developed a sports-themed program, bringing other stars—professional baseball and football players as well as Olympic athletes—inside correctional facilities to perform athletic feats and share the gospel. Many would play catch or accept physical challenges from prisoners, the theatrics at the events guaranteeing large crowds.

Occasionally the showmanship proved dangerous. In 1982, a young University of North Carolina basketball player named Michael Jordan joined Glass in a prison visit and volunteered for a samurai swordsman’s demonstration that involved cutting a watermelon on Jordan’s stomach. The swordsman’s blade went too far, leaving Jordan with a gash that required three stitches at the local emergency room.

Glass was horrified by the accident, but he also believed that athletic spectacles offered him a chance to share the gospel with people who might not otherwise be interested. In classic entrepreneurial evangelical style, he intentionally avoided ministry expressions that appeared “churchy” and eschewed prison chapels as sites for his events. He chose instead to hold most of his crusades outdoors, on the yard or on prison ballfields. He believed that many incarcerated people had no interest in the chapel, and “those are usually the inmates we are the most concerned about reaching.”

Blessing incarcerated people

While his crusades’ feats showcased athletic prowess and power, Glass’s messages in his preaching and writing were intensely relational, stressing the importance of intimacy and emotional connection. Glass often spoke of the need for incarcerated men to experience “the Blessing,” a sense of love and belonging. In Glass’s estimation, many prisoners were incarcerated precisely because they lacked unconditional love, encouragement, and physical affection from father figures. They needed to know the love of their heavenly Father and experience the intimate fellowship of Christian believers (including Christian prison volunteers) who might act as “substitute fathers.”

Because of his focus on fatherhood and changing individual prisoners’ hearts, Glass rarely spoke of systemic injustices or the problems of the criminal justice system itself. And while he saw racial reconciliation as an outcome of his prison work, his avowed colorblind racial emphasis could reinforce a blindness to racial disparities.

But Glass’s gospel message resonated with many incarcerated people, evidenced by testimonies and letters from prisoners thanking him for his ministry’s positive impact in their lives and his clear concern for their spiritual and emotional well-being. Glass also inspired many other Christians to get involved in prison ministry, often after they had volunteered to work at one of his crusades.

“The thing we did for prison ministry,” Glass said near the end of his life, “was that we popularized it. We made it something people wanted to do.”

By the end of his career, Glass claimed he had been in more prisons than “any man that’s ever lived.” It’s impossible to verify the claim, but it is certain that Glass made a lasting impact in prisons and on playing fields.

“Christianity does not teach a withdrawal from life, but an infiltration of it,” Glass explained in his first book. By ministering in spaces that evangelicals had previously avoided, Glass taught future generations of evangelicals to do the same.

Glass is survived by his three children, Billly, Bobby, and Mindy. A memorial service will be held December 18 at Waxahachie Bible Church in Waxahachie, Texas.