There’s one thing that all evangelical Christians in Ethiopia can agree on: Three years ago, when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed came to power, their country was transformed.

The transition to an ethnically Oromo leader marked a break from 27 years of rule by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). And in a country historically dominated by Orthodox and Muslim believers, Abiy became the first openly evangelical head of government Ethiopia ever had.

But since a bitter and violent conflict broke out between Abiy’s government and the formerly ruling TPLF in the northern Tigray region in November 2020, evangelicals—who make up just over 18 percent of the population—have been divided over how to respond.

The majority, according to Christian Ethiopians and ministry workers in Ethiopia that I interviewed, support the military operation. Their support has held strong even as reports of civilian deaths, ethnic cleansing, horrific human rights abuses, and widespread hunger inflicted on the Tigrayan population rise in scale and urgency.

Earlier this month, the UN announced that more than 350,000 people in the Tigray region are already living in famine conditions, with another 1.7 million approaching famine. While the national government this week unilaterally declared a ceasefire after Tigrayans recaptured their regional capital, the TPLF is vowing to continue the fight.

Mazaa (a pseudonym), a 44-year-old who runs a K–8 school with her husband outside of Addis Ababa, has tried to share her concerns about the grave suffering of Tigrayans with fellow evangelicals. She asked not to be named out of fear of retribution against her students’ families.

Her school near the capital city serves a number of Tigrayan families; she has seen firsthand how the fathers of her students have been “disappeared,” and then how the surviving widows and children are isolated socially and economically. Her friends’ response? “These people brought it on themselves. It’s not without cause.”

“I don’t care what the cause is,” Mazaa told me. “Jesus says we have to love one another. Love doesn’t take any conditions. The love we offer and give has to be without any condition.”

She also believes the war is unnecessary. The dispute between Abiy and the TPLF “should have been resolved another way. Fighting could have been avoided, if there was dialogue or reconciliation or willingness on their part to go through a lot of steps.”

But Mazaa is in a relatively small minority. Among non-Tigrayan evangelicals, the justification for the war extends decades back. Under the TPLF, Protestantism was treated like a second-class religion. Muslims and Orthodox Christians were given preference in myriad ways, from political access to venue options for worship services. That’s on top of the large-scale oppression perpetrated by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), the ruling coalition dominated by the TPLF, which regularly jailed dissidents, censored the internet and media, and limited individual freedoms.

Before the TPLF, when Ethiopia was under imperial and then Communist rule, the oppression against evangelical Christians was even worse, with regular executions and imprisonments. But all that changed with Abiy’s unexpected rise to power. He freed thousands of political prisoners, unblocked hundreds of websites, facilitated the end of a schism within the Orthodox church—and promoted long-awaited equity for evangelical Christians.

In Ethiopia, the term “Pente,” which began as a nickname for Pentecostals, has come to refer to evangelicals and most Christians outside the Orthodox Church. The prime minister attends a Pente church whose denomination is part of the Evangelical Churches Fellowship of Ethiopia.

“Right now, the evangelical Christian is getting more attention, is getting rights, is getting more opportunities to be part of the political movement because we’re being led by an openly evangelical Christian,” explains Eshe (a pseudonym), who works for two evangelical ministries and attends a Mennonite-affiliated church in Addis Ababa.

She does not support how Abiy is handling the conflict, and she expressed concern that her views could get her labeled as part of the “opposition.” But for many other evangelicals, Abiy is a gift from God, an anointed leader, and even a prophet.

Abiy’s many political and social reforms have been widely celebrated across Ethiopia—and the world. Up until last year, Abiy was best known as the man who made peace with longtime foe and neighbor Eritrea, which resulted in the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize.

But the evangelicals’ gain has been the Tigrayans’ loss, including evangelicals living in the Tigray region, which is home to a higher concentration of Orthodox Ethiopians and their holy sites. According to a recent statement from the Evangelical Churches Fellowship of Tigray Region:

Tigray has been ravaged by a war of revenge, destruction, and death. The damage to the people of Tigray is immeasurable, and the enormity of the need of millions of people is great and pressing.

One of the unforeseen and unexpected experiences of the current conflict has been the fact that the leadership of the Ethiopian Evangelical church has supported this evil war against the population of Tigray. The Ethiopian Evangelical church has lent its financial and unwavering spiritual support to the Ethiopian government through false prophecy of guidance and praying for the success of the military mission against the people of Tigray.

That evangelical support seems to be rooted in a particular interpretation of what God is doing in the current conflict. Many evangelical Christians see the events in Tigray as the judgment of God. Several of the Ethiopian Christians I interviewed said their friends and family readily declare that the Tigrayans “deserve what they get.”

Biruktawit Tsegaye, a 27-year-old volunteer with an evangelical college ministry, believes the TPLF laid the groundwork for the current conflict.

“TPLF corrupted the nation, the people, based on ethnicity. TPLF sowed a bad seed based on ethnicity, so the nation is divided. TPLF is based on differentiating and dividing the nation in the past 20 years,” she explained to me. “After that, with the new government coming in, they refuse to participate and accept the new change. That is the main reason for the division and the war.”

Her friend Desalajn Assefa Alamayhu, an evangelist who is Tigrayan himself, agrees. And he accuses Christians in Tigray of being active contributors to the conflict.

“Tigray Christians participate in evil things with TPLF. They participate completely with TPLF. They said, ‘In [the] Bible, we can oppose federal government because we need freedom.’” In contrast, he contends, “most Christians in Ethiopia agree with the federal government because Dr. Abiy teaches and preaches from the Word of God.”

But to Eshe, a just response to past offenses and the current insubordination of the TPLF should not have been a large-scale conflict.

“It was just between two political parties. The leaders are the ones in conflict,” she explains. Eshe believes that the previous TPLF leaders who committed serious crimes number less than a hundred. Abiy’s government should have simply gone after those individuals instead of “taking war as a solution.”

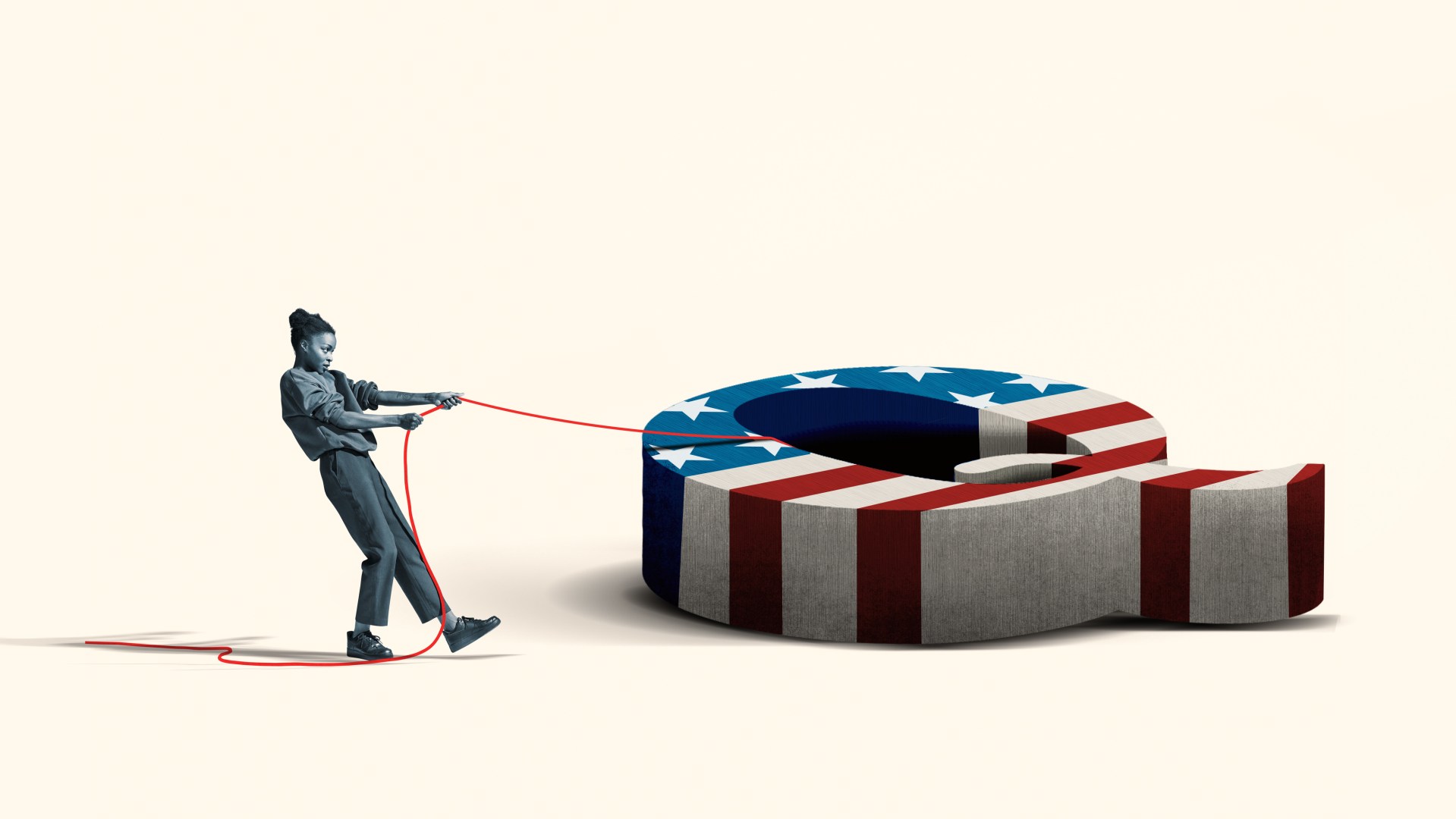

The question that many evangelical Ethiopians seem to be wrestling with is this: With whom would Jesus side—the charismatic evangelical leader determined to defeat his enemies, or the primarily nonevangelical Tigrayans who are suffering immensely?

Where they ultimately land is complicated by the fact that media reports and even interpersonal communications coming out of Tigray have been tightly controlled; misinformation and propaganda abound. And under a government that has shown itself increasingly willing to punish dissidents, there is the real threat that vocal opponents of the war could be jailed—or worse.

For Kofi (a pseudonym), where his loyalty lies is clear.

“For me, as a Christian, our allegiance is with God first. The Bible says we have to ally with those who are hurt,” said the 26-year-old, who declined to be named to protect his missions agency, which partners with churches and evangelizes in Tigray.

“That’s one of the things that Christ says to the disciples: Cry with those who are crying, share with those who don’t have nothing. We have to be with those who are suffering. No matter the political explanation, I don’t care. That’s not the primary need. There are many who are suffering and in need of our prayers and help.”

Editor’s note: A citation of theologian Paulos Fekadu has been removed from this article due to his claim that the linked publication mistranslated his position.