The biggest debate on social media this weekend has been over the appropriate level of concern for a significant, long-term disruption of daily activities because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The disagreement skews partisan, with new surveys showing Republicans are far less likely than Democrats to fear the coronavirus outbreak in the US.

In recent years, Americans across religious traditions have become more worried about the potential for a major epidemic, the kind of hypothetical question that has become all too real in the past few weeks.

But the earlier data shows fears around the spread of disease tend to be lower among Protestant Christians who identify as politically conservative and attend church weekly. This may explain why some conservative leaders, including a couple of President Donald Trump’s evangelical advisers, hesitated to cancel in-person worship or on-campus classes amid the current coronavirus precautions.

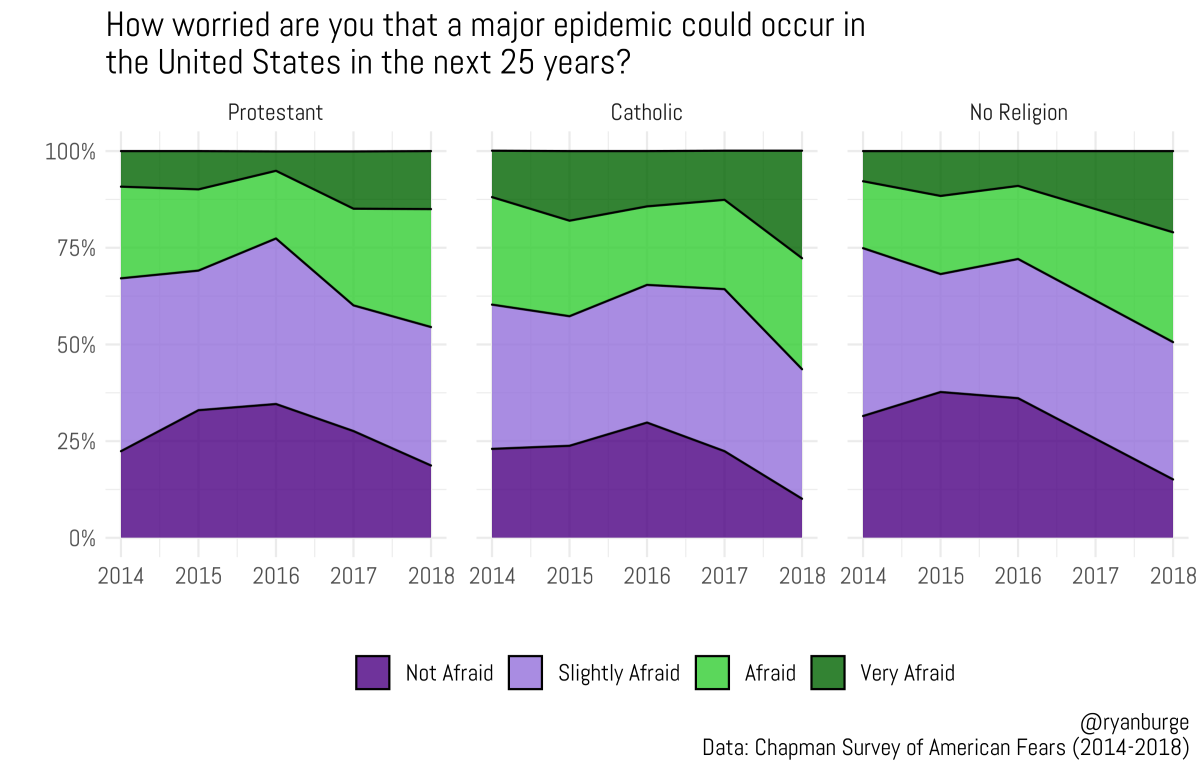

Starting in 2014, the Chapman Survey of American Fears asked respondents to its annual survey, “How worried are you that a pandemic or a major epidemic could occur in the United States in the next 25 years?” to gauge public sentiment around common phobias, spiritual forces, and natural disasters. From 2014 to 2018, concern over potential pandemics rose. Fewer people across religious groups said they were “not afraid” about the possibilty of a new disease spreading in our country.

When the survey began in 2014, most were not that worried. Two-thirds of Protestants and 60 percent of Catholics were not afraid or just slightly afraid of a major epidemic, and those of no faith tradition were far less concerned, with three-quarters saying they were not afraid or slightly afraid.

Four years later, the concern had increased significantly. Just half of the “nones” and even fewer Catholics (43.6%) landed in the less-afraid categories. By some measures, Protestants, however, became a bit more moderate. They had a much smaller share who said that they were “very afraid” of a pandemic—15 percent of Protestants compared to about twice as many Catholics (27.8%).

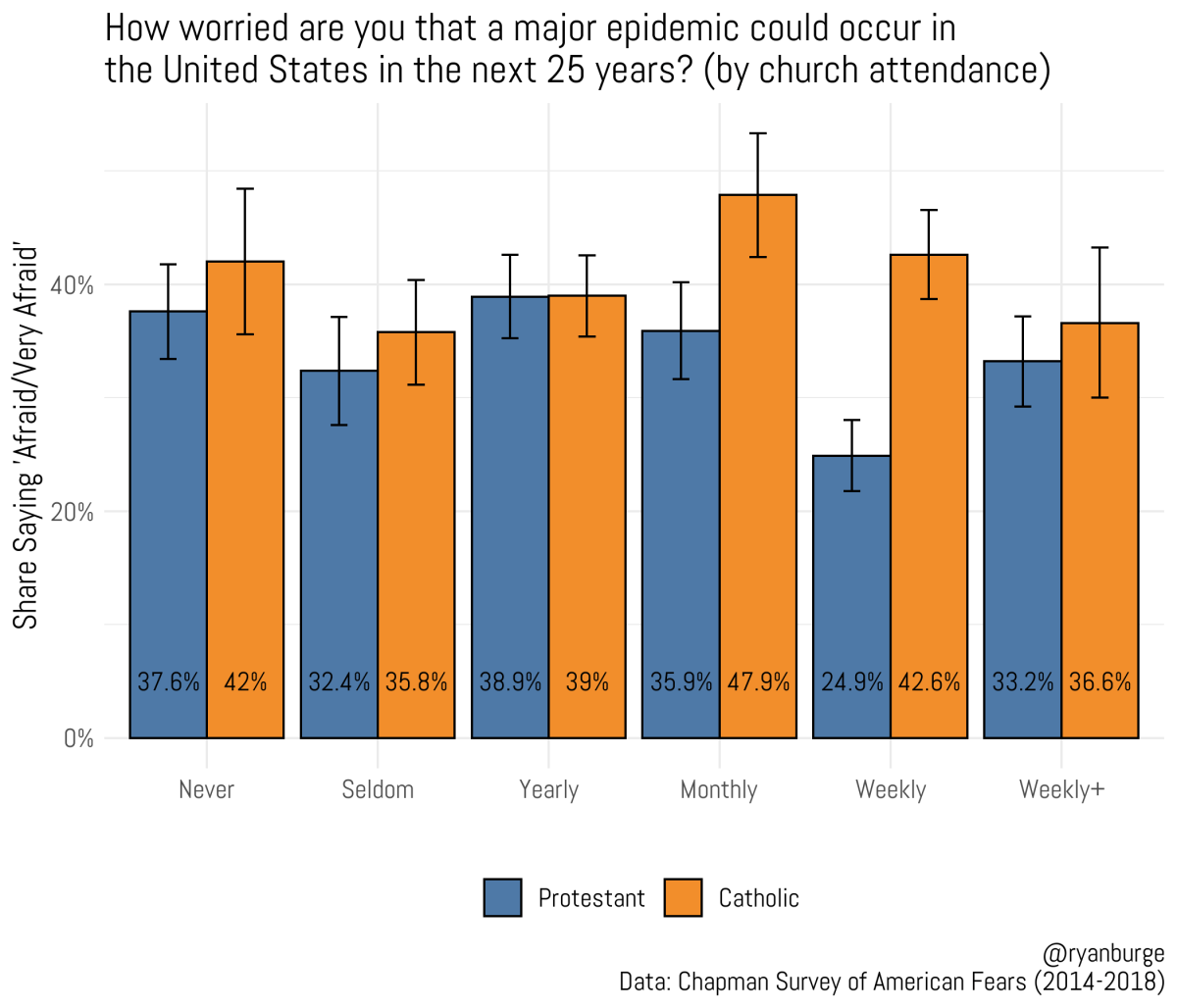

How much does religious devotion affect Americans’ levels of fear? It would seem likely that the more often people attend church services, the more exposure they would receive to the biblical admonitions to run from fear, to “be strong and courageous” and “do not be afraid or terrified … for the Lord your God goes with you” (Deut. 31:6).

The statistical evidence is mixed, however. Protestants and Catholics who never attend church are only slightly more likely to say they’re afraid of a major epidemic than those who go more than once a week.

Additionally, there doesn’t seem to be a significant difference between Protestants and Catholics, except that Protestants who go to church weekly have a much lower level of fear over epidemics (24.9%) than weekly Mass–attending Catholics (42.6%). Their level of fear also falls lower than fellow Protestants who attend more or less than they do.

The concern around the severity of COVID-19 can depend on political orientation. For instance, a recent Quinnipiac University poll, conducted the first week in March, found that 63 percent of Republicans were not especially concerned about the virus, compared to 31 percent of Democrats.

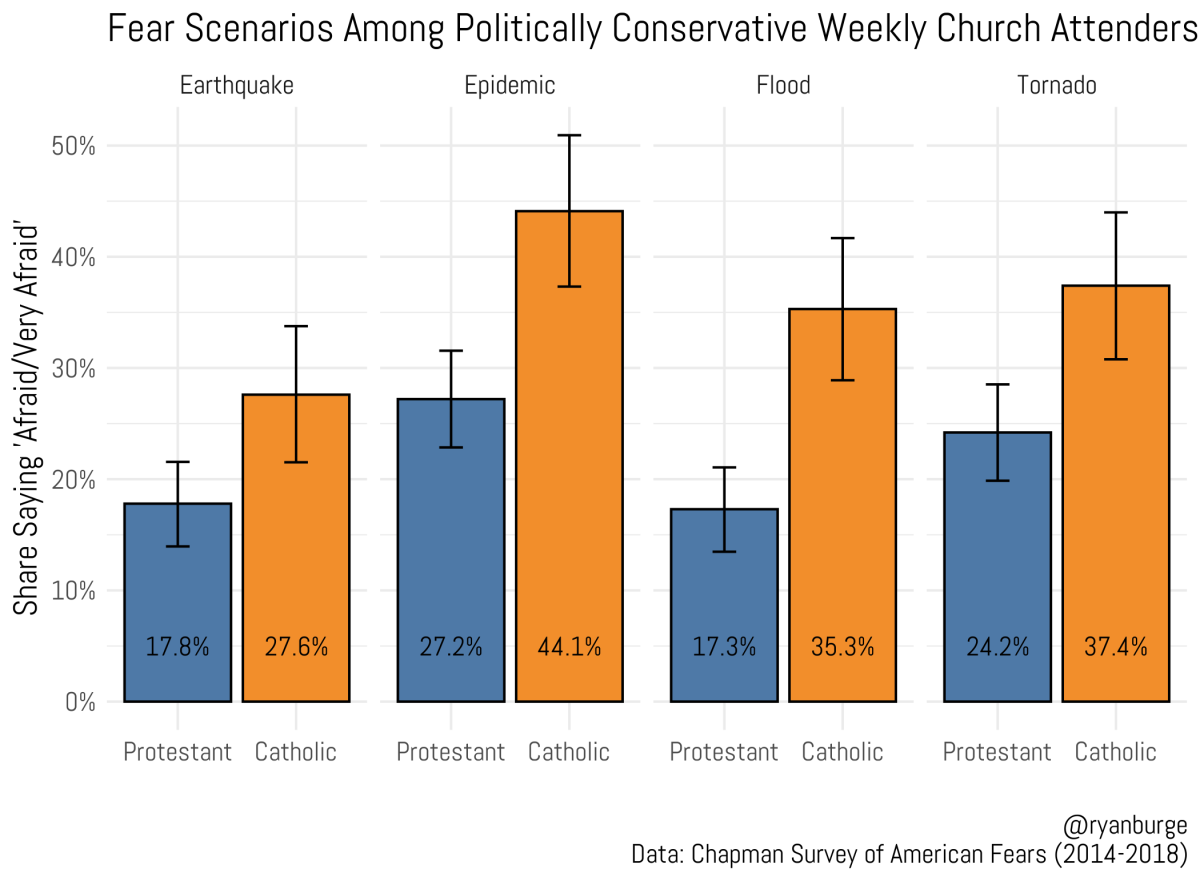

In the Chapman Survey, when looking just at regular churchgoers who described their political ideology as conservative, a clear outlier emerges. Politically conservative Protestants who attend church frequently are far less concerned with a major epidemic than conservative, devout Catholics.

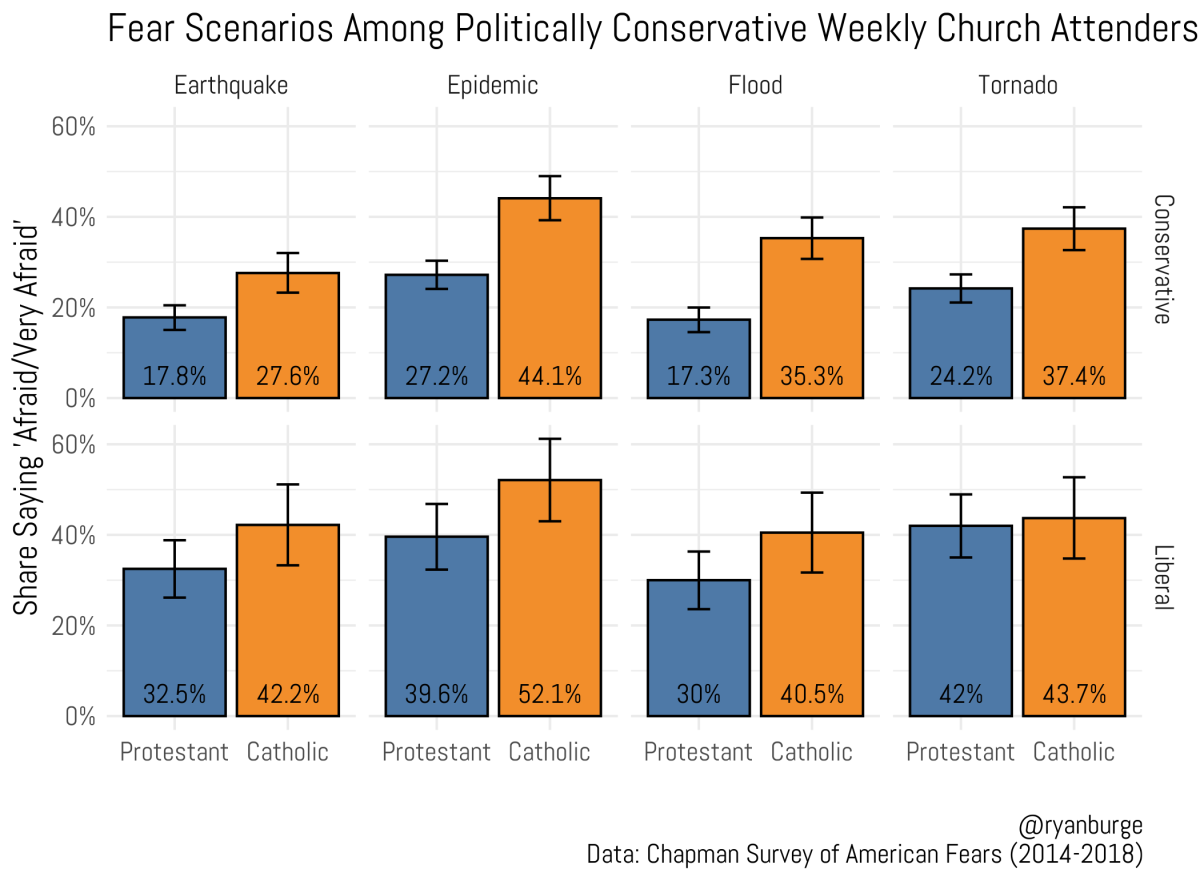

Just one in four of these Protestants (27.2%) has indicates being afraid or very afraid of the possibility of a disease outbreak. That’s 17 points lower than conservative Catholics. But, it’s clear that the overall level of fear is lower among conservatives in general. The data indicate that politically liberal Christians espouse higher levels of fear regardless of church tradition.

Josh King, a pastor at an Arkansas church, provided a timely example of this when he told the Washington Post: “In your more politically conservative regions, closing is not interpreted as caring for you. It’s interpreted as liberalism, or buying into the hype.” And data released Sunday from an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll indicates that Democrats are twice as likely to avoid large gatherings because of COVID-19 as Republicans.

This low level of fear that politically conservative Protestants express is not just isolated to the fear of a major epidemic but extends to other natural disasters as well, according to the Chapman Survey data. Fewer than one in five conservative Protestants are worried about an earthquake or flood—that’s 10 points less than conservative Catholics. For liberal Protestants, fear of natural disasters is typically 10 to 15 percentage points higher.

It’s not that conservative Protestants are especially unconcerned about the possibility about a disease outbreak; they seem generally unphased by many things that are outside their control.

Projecting the appropriate level of concern to the general public surrounding a possible health emergency is an ongoing struggle for public health officials. When people become panicked, they often behave in irrational ways, like causing a nationwide toilet paper shortage. However, medical professionals need the public to engage in practices like rigorous hand washing and social distancing to impede the spread of COVID-19.

These results indicate that some segments of the American population would be more prone to fall into panic, while other groups may be more reluctant to change their behavior based on a lower baseline of concern.

In some evangelical Protestant traditions, fear can also be seen as a betrayal of faith. A group out of Bethel Church—including aspiring politician Sean Feucht, who led worship in the Trump White House last year—is releasing messages online in response to the spread of coronavirus, aiming to “silence voices of fear.” Bethel leader Bill Johnson told followers, “This whole maneuvering in fear is crazy. I've never seen the spirit of fear spread so quickly. Internationally, things were many, many, many, times worse.”

But while many politically conservative Protestants may have historically been less likely to worry about an epidemic, the daily updates in the US are rapidly changing their approach. More conservatives and evangelical leaders are taking a hardline stance on the coronavirus response, particularly as many rallied Sunday for the President’s National Day of Prayer.

Trump said he tuned into a livestreamed worship service led by one of his evangelical advisers, Georgia pastor Jentezen Franklin, who had canceled in-person gatherings at his church.

Trump wrote in his prayer declaration on March 14:

On Friday, I declared a national emergency and took other bold actions to help deploy the full power of the Federal Government to assist with efforts to combat the coronavirus pandemic. I now encourage all Americans to pray for those on the front lines of the response …

We are confident that he will provide them with the wisdom they need to make difficult decisions and take decisive actions to protect Americans all across the country. As we come to our Father in prayer, we remember the words found in Psalm 91: “He is my refuge and my fortress: my God; in him will I trust.”

Ryan P. Burge is an instructor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.