Ray Bakke believed that “Jesus loves the little children / All the children of the world,” and he thought evangelicals did too. So he was surprised when so many fled from racial diversity when their children’s schools were integrated.

“It was the biggest shock of my life,” he told CT in 2021. “The whole Moody-Trinity-Wheaton establishment, all of them singing ‘red and yellow, Black and white,’ but when those kids showed up at their kids’ schools, they panicked and they fled.”

Bakke went the opposite direction. He moved his family into Chicago in 1965 and stayed through white flight, racial unrest, riots, bombs, fires, and gangs. He adopted a Black son and became a leading proponent of urban missiology, arguing that the Great Commission called Christians into American cities.

Bakke was a critic of suburban Christianity and a bold voice opposing church growth strategies that embraced and encouraged de facto racial segregation.

“He taught us urban missiology in ways few of us were prepared to see in the ’80s,” said David Fitch, chair of evangelical theology at Northern Seminary. “He gave us a vision for how God works in the teeming diversities of urban centers. He had a giant presence wherever he spent time with pastors and students.”

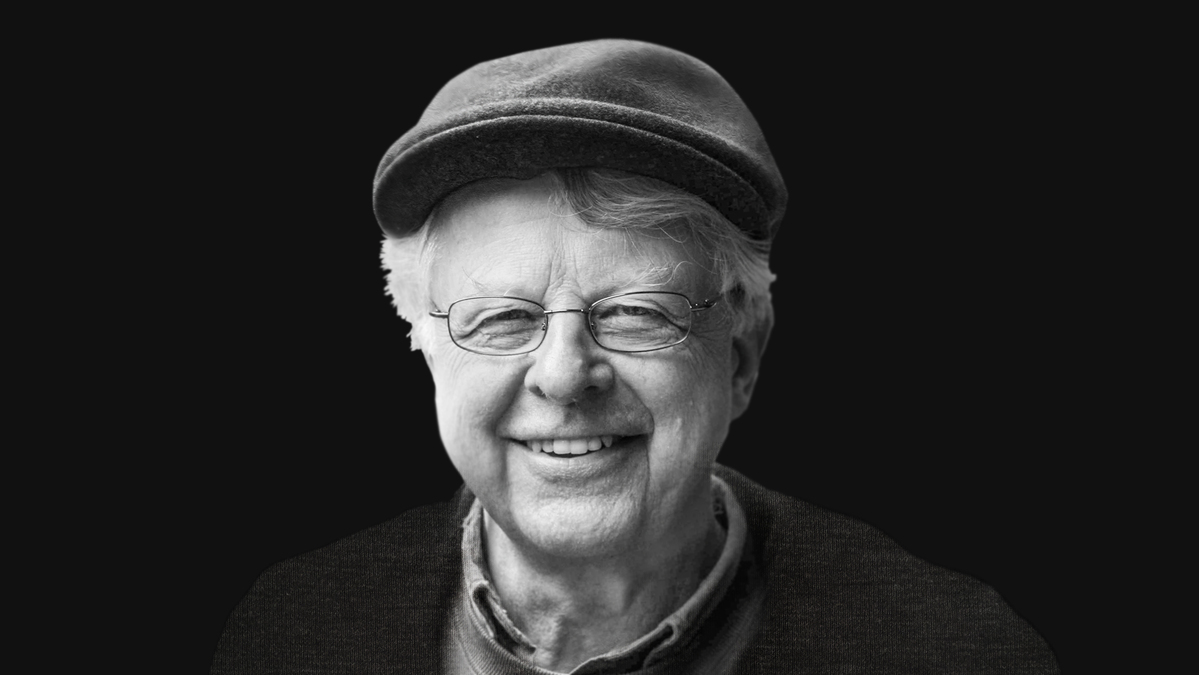

Bakke died on February 4 at the age of 83. His family requested that CT hold his obit until February 28 to give them time to grieve.

The author of The Urban Christian and A Theology as Big as the City was raised about as far from city lights as one could get. His parents, Tollef and Ruth Bakke, settled in Saxon, Washington, about 90 miles north of Seattle, in a valley between the Cascade Mountains and Lake Whatcom, where a community of immigrant loggers and farmers raised children and cows.

Tollef and Ruth both came from Norwegian families but spoke in different dialects and couldn’t understand each other, so the first language in their home was English. Tollef had once hoped to go to Bible school, but the dream was interrupted by the Great Depression. He had a dairy farm, drove a truck, and was an active member of a local Lutheran church with a deep commitment to personal faith, prayer, and Bible reading.

Ray Bakke was born May 22, 1938, the oldest of four. He was taught Sunday school by “a busted-up Swedish logger,” he told CT, who believed Christians should love God, follow Jesus, and serve the world.

A high school history teacher and football coach encouraged Bakke to go study at Moody Bible Institute and “get a little Bible under your belt.” He left Washington on a bus at 18, with a box of chicken and sandwiches his mother had packed.

“I didn’t know where Moody was,” Bakke said in an interview two months before his death. “When we came down Lake Shore Drive in Chicago, I was in awe of everything I saw. I was captured by Moody.”

Studying to be a pastor from 1956 to 1959, Bakke was exposed for the first time to the racial divisions in America.

One of the people he learned from was Corean Jantz, a piano major and pastor’s daughter from Missouri. Jantz was the pianist for the Moody choir, and her roommate, the choir’s best soloist, was Anita Bingham, a Black woman. When the choir traveled, school officials called ahead to warn churches that the choir was integrated. Bakke was startled to learn that some Christians would refuse to let a Black student into their homes.

Bakke married Jantz in 1960, and the young couple moved to Seattle, where Bakke pastored at a Swedish Baptist church and continued his education at Seattle Pacific University.

As a young pastor, Bakke said, he learned he also had to be a part-time sociologist. To minister to his congregation, he had to understand the social pressures impacting their faith. When a local Boeing plant lost a government contract and laid off large numbers of employees, the effect was felt at the Swedish Baptist church.

“I began, overnight, to lose men,” he said. “When the lunch bucket group, working-class men, are unemployed, they stop coming to church. They’ve lost their identity. If they don’t have a job, they don’t have an identity. These sturdy evangelical believers found it difficult to come to church.”

Bakke decided he needed more education. Then the family suffered a personal tragedy when a daughter died at birth. They buried her and left Seattle. The family—Ray, Corean, and sons Woody and Brian—moved back to Chicago in 1965.

Bakke enrolled in Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and pastored a church in the Edgewater neighborhood of Chicago, where about 60,000 people lived in a 1.25-square-mile area, including immigrants from about 25 percent of the nations of the world. He recognized his cultural context was, in some important ways, similar to the urban context of Christians in the Roman Empire. Paul wrote to churches in diverse metropolises; Augustine wrote about the Trinity while ministering to Christians in the port city of Hippo.

And yet, in an evangelism class at Trinity, he learned there was no major scholarship on urban evangelism and that some even argued that Christianity couldn’t thrive in cities, because the Bible was a rural book for rural people.

As an evangelical, though, Bakke felt called to love God, follow Jesus, and serve the world. And the world’s people were increasingly urban.

“We can all be timid Christians, when faced with modern urban conditions,” Bakke later wrote. “But it is only by living in a city, with a theological vision for the city, that we can attempt to reach the city’s people.”

When Bakke graduated from Trinity, he entered the doctoral program at McCormick Theological Seminary, writing his dissertation on urban pastoral work in the Roman Empire and laying the foundation for a modern urban missiology.

As a doctoral student, he cofounded the Seminary Consortium for Urban Pastoral Education, which is now a school at Christian Theological Seminary. When he graduated, he took a position as professor of ministry at Northern Seminary and joined the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelism as the senior associate for large cities.

Bakke’s work ran against popular trends in the study of evangelism, though. Many evangelicals in the 1980s and ’90s embraced a church growth strategy based on the “homogeneous unit principle” that said more people will convert to Christianity if they don’t have to cross racial, linguistic, or class barriers.

Bakke personally quarreled with Fuller professor C. Peter Wagner about church growth theology.

“Peter once pushed up against the wall of a bookstore,” Bakke said. “He said, ‘If 2 billion have never heard the gospel, isn’t it true that reaching them is more important than your theology of the city?’

“I told him that gangs are segregated and they grow, but that doesn’t mean they’re good. There is something missing if your church growth theology isn’t better than what the gangs are preaching.”

At the same time, integration wasn’t an abstract idea for Bakke. His sons were enrolled in public school, and Woody, his eldest, frequently brought friends who didn’t have enough to eat to the Bakke house. One of them, a boy named Brian Davis, stayed for weeks and then months, until the Bakkes finally asked if he wanted to be a permanent part of the family.

“People talk about how hard it is to integrate,” Bakke told CT. “It only cost me $80 to adopt him.”

In 2001, Bakke cofounded Bakke Graduate University. The school focused on teaching pastors to apply theology to trends in urban migration and the growth of global cities. Two-week intensive courses are held in six continents, and each student must cross an ocean at least once as part of the program. Bakke worked there as chancellor and professor until he retired in 2011.

He continued to be frustrated, though, that so many white evangelicals didn’t seem to believe the Sunday school song about Christ’s love for racial diversity.

“I watched the evangelical movement panic and turn inwards,” he said a few months before his death. “We’ve become fearful as the country has become fearful, and politicians have played on that fear. Too many white evangelicals have forgotten who we are. We are the people who believe in crossing oceans and jungles and talking to people in their own languages. Now we’re moving into all-white neighborhoods and hoping the globalization stuff will go away.”

Bakke said he hoped Christians would reread Psalm 107 when he died and remember that God is on a mission in the motion of people around the globe.

He was predeceased by his son Brian Davis in 2018 and wife, Corean Jantz Bakke, in 2021. He is survived by his sons Woody and Brian Bakke.