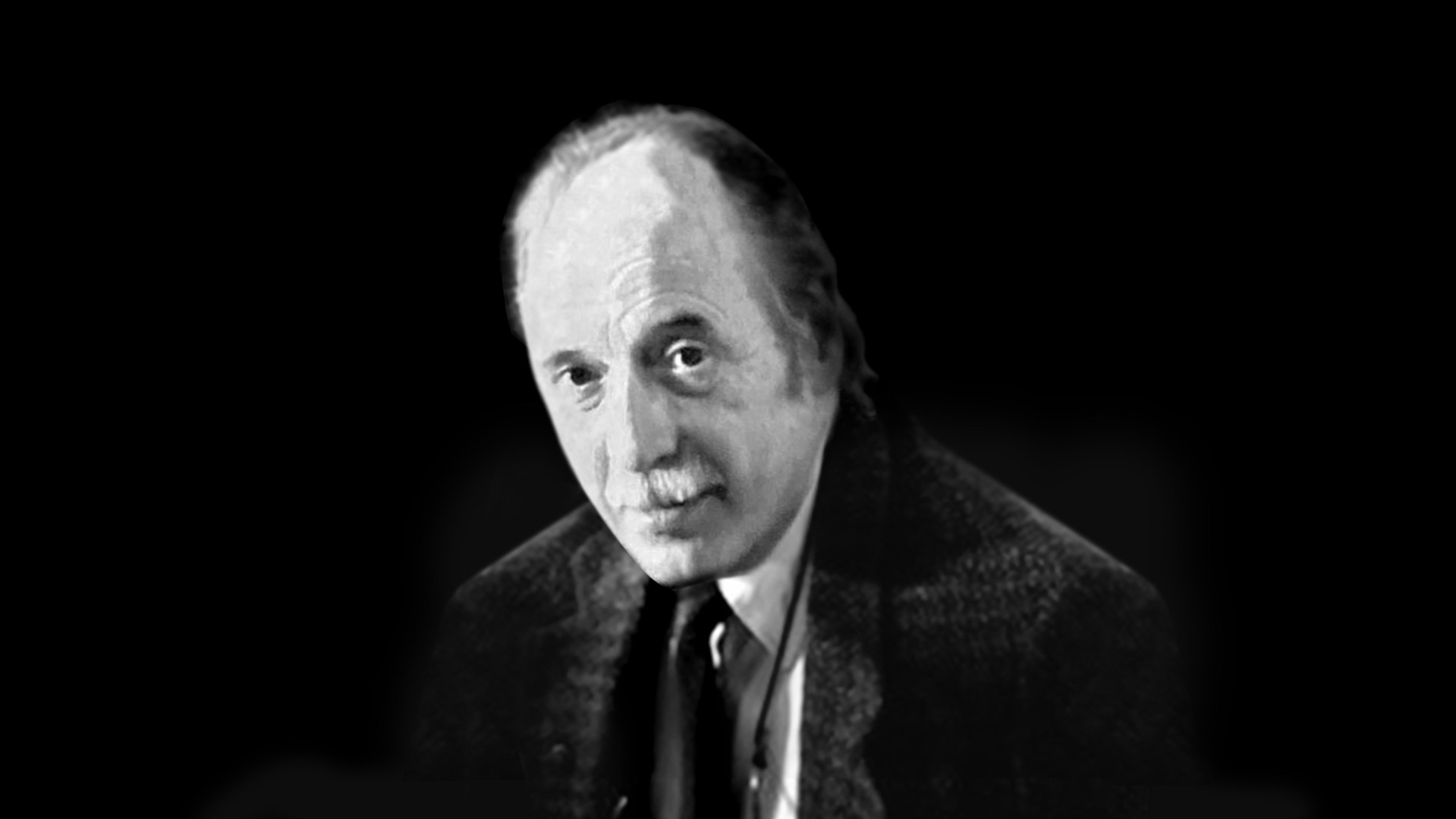

Franz Mohr, former chief concert technician at Steinway & Sons in New York, has died at 94.

He was, in his own assessment, “just a piano tuner who loves the Lord.”

But Mohr’s expertise and backstage support was valued by the world’s most famous concert pianists, including Van Cliburn, Vladimir Horowitz, Artur Rubinstein, Glenn Gould, Rudolf Serkin, and Emil Gilels. They relied on his deep musical knowledge and technical skill.

He traveled around the world with them, protecting and servicing their concert-grade grand pianos, each of which was built by 200 Steinway & Sons artisans and cost more than $200,000. Mohr prepared the pianos with tuning, voicing, and adjustments for optimal performance to the artist’s particular liking. Between concerts, he could be found in Steinway Hall’s basement in Manhattan, doing regular, meticulous maintenance.

His true passion, however, was unashamedly proclaiming the love and hope of Christ to this niche community.

“He was like a magnet drawing them in,” said Tom Carpino, Franz’s pastor at The Bridge (Nazarene) Church, in Malverne, New York, “and bringing the Bible’s message to whomever he could.”

Franz was a member of The Bridge for more than 40 years and served for many years as an elder. He also regularly spoke to Christian groups and worked with Crescendo International, a Cru ministry.

“With my little tuning hammer I have shared the Lord in unbelievable places,” he said.

He died at home on March 28 from complications related to COVID-19.

Mohr was born in Nörvenich, Germany, on September 17, 1927. He was the second of three sons in a musical family in which Mendelssohn, Mozart, and Beethoven were as familiar as bratwurst and potatoes. His father, Jakob, was a postal worker who enjoyed singing and playing the guitar, mandolin, and zither.

Mohr played the violin and viola and studied music in Cologne and Detmold.

Adolf Hitler’s rise to power and the subsequent war completely transformed Mohr’s idyllic world and threw him into a spiritual crisis that lasted many years.

At the age of 17, on November 16, 1944, he lived through an air raid. As he later recalled, he was sitting on the roof of his family home watching the sky when he sensed something terrible was about to happen. Everything got quiet and the rabbits and chickens in the backyard huddled together in a corner and refused food.

Searching the horizon, he saw waves of incoming planes, flying low toward Düren. He rushed to the family bomb shelter with his parents and younger brother, Peter. Within 20 minutes, 1,800 B-17 bombers obliterated the city.

As the bombs fell in the darkness, his mother, Christina, cried to God for help. Mohr screamed, “Shut up, Mom! There is no God!”

Dazed, Mohr crawled out of a hole in the shelter wall. Smoke choked the air as fires continued to burn and delayed-action bombs exploded around him.

In the confusion, Mohr was separated from his family. He fled to the countryside where a farmer took him in.

He returned to the city and reunited with his parents just before Christmas. They told him his brother Peter had died in the attack and urged him to join them at church.

Mohr exploded, “How can there be a God?”

Mohr rejected God again a few years later when an evangelical minister from Cardiff, Wales, tried to talk to him about Christ. Mohr accepted a Bible but blew off the pastor with nasty insults.

Soon after, he learned that his other brother, Tony, had been killed by Russian soldiers.

After the war, Mohr joined a Dixieland band for American soldiers, playing gigs around country. Though his life was good now that the war was over, Mohr struggled with feelings of emptiness.

He was miserable and lost. He frequently couldn’t sleep and developed an ulcer. The lifestyle made him feel despondent, but he couldn’t change. At 21 years of age, he considered suicide.

Then one restless night he decided to pray. His thoughts were drawn to Calvary and the two criminals next to Jesus on the cross, especially the one who, having trusted Jesus, heard the Lord say, “Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43).

Suddenly, he knew that Jesus took his sin. God’s love and mercy overwhelmed him. He became so excited about his new faith that he quit the band and devoured the Bible day and night.

He joined a small church and preached in the streets. Next came marriage and a family. For work, he took a position as an apprentice to a piano maker and this opened new opportunities. A German-speaking Baptist church in New York sent over an advertisement for a piano technician for Steinway, and Mohr applied and got the job. The family emigrated in 1962.

Mohr did not know, initially, how people would respond when he shared his faith in the world of concert pianists. But he believed he should tell people about Jesus anyway.

He started giving away Bibles and found they were received graciously—and sometimes with great joy.

Once, he met a young pianist from Moscow who had won the the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in Fort Worth, Texas, and was practicing in Steinway’s basement for a concert in Carnegie Hall. Following God’s leading, Mohr gave the man a Russian Bible.

Initially anxious about the pianist’s reaction, Mohr was dumbfounded when the pianist grabbed him, crying, “Franz, you have no idea what you have done. I have never in my life seen a Bible. I came to America with a desire in my heart to obtain a Bible.”

Giving Bibles to concert artists he worked for became customary. He even hid Bibles in his luggage traveling with Vladimir Horowitz for concerts in Moscow and Leningrad in 1986, when Bibles were forbidden.

The people Mohr spoke to did not always find faith. He became quite close to Horowitz, for example, but the pianist never accepted his message of Good News.

“I had opportunities a few times to talk to Horowitz about the Lord, about salvation,” Mohr wrote, “yet as far as I know, there was never any real breakthrough where with assurance I could say that he believed, and knew where he would be going after death.”

Mohr retired from Steinway & Sons in 1992 but continued working as a consultant. He wrote a memoir with Edith Schaeffer called My Life with the Great Pianists.

He also spoke in churches and looked for new opportunities to share his faith and inspire future generations of Christians.

In the early 1990s, Mohr connected with Crescendo International, a Cru ministry based in Basel, Switzerland, that links professional musicians and music students with Christians via lectures and events in concert halls, festivals, and churches.

Mohr served Crescendo for more than 20 years as a director and speaker, touring annually in Europe. He lectured on concert piano techniques, weaving his testimony into every lesson.

“Franz was so relaxed, speaking in a natural way about God,” said Beat Rink, Crescendo founder and international director. “His lectures also encouraged Christians to be more open in sharing the gospel.”

According to Mohr’s son Michael, director of restoration and customer services at Steinway & Sons, Mohr remained spritely and in good health until around mid-2021. During Mohr’s final days at home, he comforted his family saying, “Don’t worry, the best days are yet to come.”

He is survived by his wife, Elisabeth, along with Michael, his daughter Ellen, seven grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. His son Peter died in 2019.