They were right. I was wrong to call sexual abuse in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) a crisis. Crisis is too small a word. It is an apocalypse.

Someone asked me a few weeks ago what I expected from the third-party investigation into the handling of sexual abuse by the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee. I said I didn’t expect to be surprised at all. How could I be? I lived through years with that entity. I was the one who called for such an investigation in the first place.

And yet, as I read the report, I found that I could not swipe the screen to the next page because my hands were shaking with rage. That’s because, as dark a view as I had of the SBC Executive Committee, the investigation uncovers a reality far more evil and systemic than I imagined it could be.

The conclusions of the report are so massive as to almost defy summation. It corroborates and details charges of deception, stonewalling, and intimidation of victims and those calling for reform. It includes written conversations among top Executive Committee staff and their lawyers that display the sort of inhumanity one could hardly have scripted for villains in a television crime drama. It documents callous cover-ups by some SBC leaders and credible allegations of sexually predatory behavior by some leaders themselves, including former SBC president Johnny Hunt (who was one of the only figures in SBC life who seemed to be respected across all of the typical divides).

And then there is the documented mistreatment by the Executive Committee of a sexual abuse survivor, whose own story of her abuse was altered to make it seem that her abuse was a consensual “affair”—resulting, as the report corroborates, in years of living hell for her.

For years, leaders in the Executive Committee said a database—to prevent sexual predators from quietly moving from one church to another, to a new set of victims—had been thoroughly investigated and found to be legally impossible, given Baptist church autonomy. My mouth fell open when I read documented proof in the report that these very people not only knew how to have a database, they already had one.

Allegations of sexual violence and assault were placed, the report concludes, in a secret file in the SBC Nashville headquarters. It held over 700 cases. Not only was nothing done to stop these predators from continuing their hellish crimes, staff members were reportedly told not to even engage those asking about how to stop their child from being sexually violated by a minister. Rather than a database to protect sexual abuse victims, the report reveals that these leaders had a database to protect themselves.

Indeed, the very ones who rebuked me and others for using the word crisis in reference to Southern Baptist sexual abuse not only knew that there was such a crisis but were quietly documenting it, even as they told those fighting for reform that such crimes rarely happened among “people like us.” When I read the back-and-forth between some of these presidents, high-ranking staff, and their lawyers, I cannot help but wonder what else this can be called but a criminal conspiracy.

The true horror of all of this is not just what has been done, but also how it happened. Two extraordinarily powerful affirmations of everyday Southern Baptists—biblical fidelity and cooperative mission—were used against them.

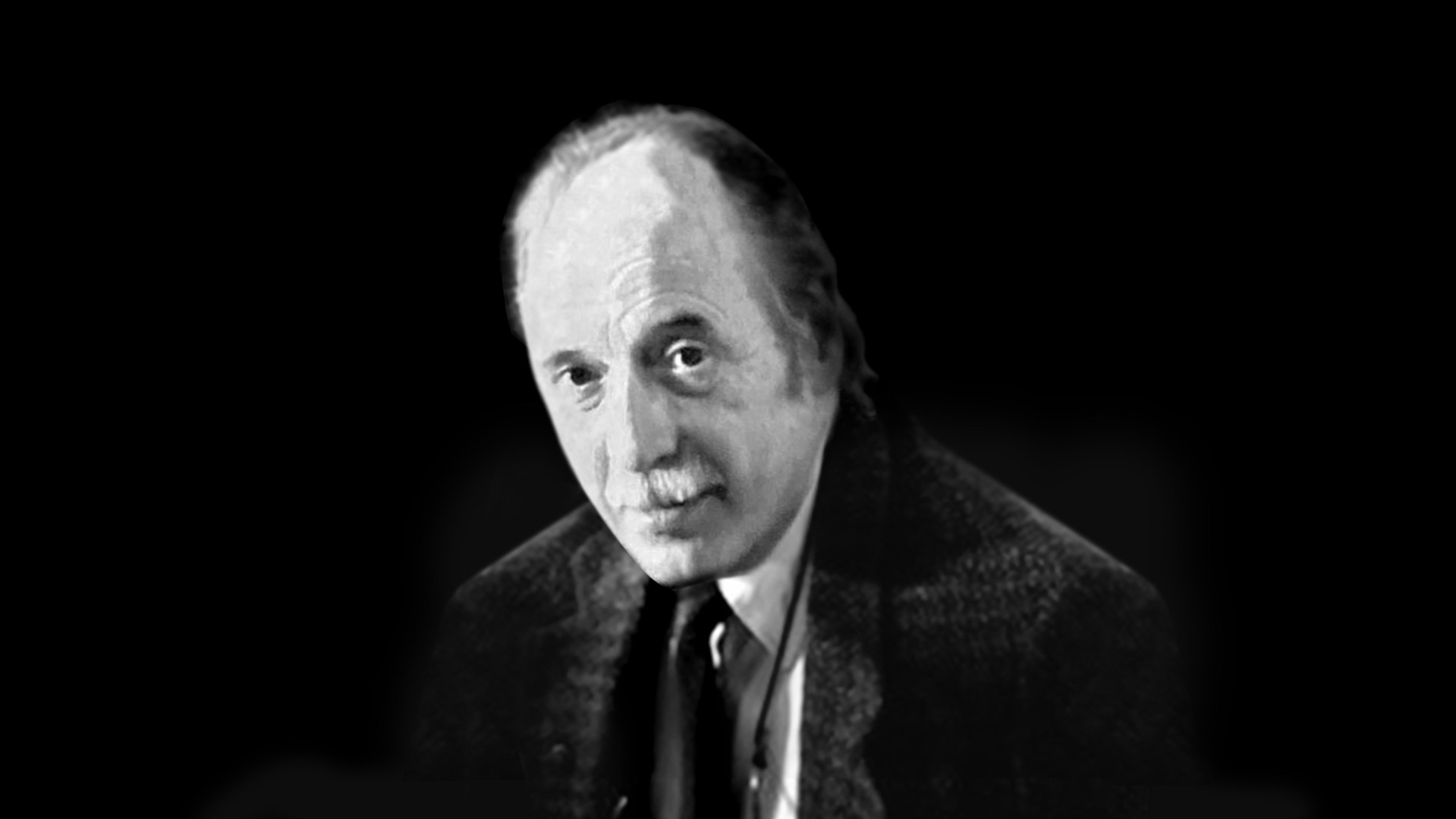

Those outside the SBC world cannot imagine the power of the mythology of the Café Du Monde—the spot in the French Quarter of New Orleans where, over beignets and coffee, two men, Paige Patterson and Paul Pressler, mapped out on a napkin how the convention could restore a commitment to the truth of the Bible and to faithfulness to its confessional documents.

For Southern Baptists of a certain age, this story is the equivalent of the Wittenberg door for Lutherans or Aldersgate Street for Methodists. The convention was saved from liberalism by the courage of these two men who wouldn’t back down, we believed. In fact, I taught this story to my students.

Those two mythical leaders are now disgraced. One was fired after alleged mishandling a rape victim’s report in an institution he led after he was documented making public comments about the physical appearance of teenage girls and his counsel to women physically abused by their husbands. The other is now in civil proceedings about allegations of the rape of young men.

We were told they wanted to conserve the old time religion. What they wanted was to conquer their enemies and to make stained-glass windows honoring themselves—no matter who was hurt along the way.

Who cannot now see the rot in a culture that mobilizes to exile churches that call a woman on staff a “pastor” or that invite a woman to speak from the pulpit on Mother’s Day, but dismisses rape and molestation as “distractions” and efforts to address them as violations of cherished church autonomy? In sectors of today’s SBC, women wearing leggings is a social media crisis; dealing with rape in the church is a distraction.

Most of the people in the pews believed the Bible and wanted to support the leaders who did also. They didn’t know that some would use the truth of the Bible to prop up a lie about themselves.

The second part of the mythology is that of mission. I have said to my own students, to my own children, exactly what was said to me—that the Cooperative Program is the greatest missions-funding strategy in church history. All of us who grew up in Southern Baptist churches revere the missionary pioneer Lottie Moon. (In fact, I have a bronze statue of her head directly across from me as I write this.) Southern Baptist missionaries are some of the most selfless and humble and gifted people I know.

And yet the very good Southern Baptist impulse for missions, for cooperation, is often weaponized in the same way that “grace” or “forgiveness” has been in countless contexts to blame survivors for their own abuse. The report itself documents how arguments were used that “professional victims” and those who stand by them would be a tool of the Devil to “distract” from mission.

Those who called for reform were told doing so might cause some churches to withhold Cooperative Program funding and thus pull missionaries from the field. Those who called out the extent of the problem—most notably Christa Brown and the army of indefatigable survivors who joined that work—were called crazy and malcontents who just wanted to burn everything down. It’s bad enough that these survivors not only endured psychological warfare and legal harassment. But they were also isolated with implications that if they kept focusing on sexual abuse people wouldn’t hear the gospel and would go to hell.

Cooperation is a good and biblical ideal, but cooperation must not be to “protect the base.” Those who have used such phrases know what they meant. They know that if one steps out of line, one will be shunned as a liberal or a Marxist or a feminist. They know that the meanest people will mobilize and that the “good guys” will keep silent. And that’s nothing—nothing—compared to what is endured by sexual abuse victims—including children—who have no “base.”

When my wife and I walked out of the last SBC Executive Committee meeting we would ever attend, she looked at me and said, “I love you, I’m with you to the end, and you can do what you want, but if you’re still a Southern Baptist by summer you’ll be in an interfaith marriage.” This is not a woman given to ultimatums, in fact that was the first one I’d ever heard from her. But she had seen and heard too much. And so had I.

I can’t imagine the rage being experienced right now by those who have survived church sexual abuse. I only know firsthand the rage of one who never expected to say anything but “we” when referring to the Southern Baptist Convention, and can never do so again. I only know firsthand the rage of one who loves the people who first told me about Jesus, but cannot believe that this is what they expected me to do, what they expected me to be. I only know firsthand the rage of one who wonders while reading what happened on the seventh floor of that Southern Baptist building, how many children were raped, how many people were assaulted, how many screams were silenced, while we boasted that no one could reach the world for Jesus like we could.

That’s more than a crisis. It’s even more than just a crime. It’s blasphemy. And anyone who cares about heaven ought to be mad as hell.

Russell Moore leads the Public Theology Project at Christianity Today.