During the warm Texas spring of 2017, one couple entered their counselor’s office with trepidation. They were dating and contemplating the next step of marriage. They had even shopped for rings. But this pair, a real couple, had some baggage and wanted to ensure they were building their relationship on a solid foundation.

The boyfriend’s first marriage had ended in divorce—despite going through marriage counseling—and he still carried wounds. The girlfriend’s parents had divorced when she was a teenager, and she feared she would repeat the family pattern.

The couple’s therapist administered a variety of tests to get to know them and help them build a common language for understanding themselves and each other. One of those tests was built around the Enneagram, the personality assessment tool that has found its way into seemingly every corner of the Christian world over the past decade.

This man and the woman began a process of self-discovery, discerning their Enneagram types, becoming more aware of their defensive habits and blind spots, and working to align their thoughts, actions, and words with their goals for spiritual maturity. “We are learning new language and tools that help us rewire old habits and instincts,” they said, “encouraging us to give grace to ourselves and each other.”

Meanwhile in North Carolina, another real couple who had been married for 20 years was having a completely different experience with the Enneagram. Their marriage had its ups and downs, but the past few years had been their best. After the birth of their child in 2014, the husband threw himself back into work, which eventually strained their relationship. They started going to marriage counseling.

After a few months of therapy, things seemed to be going well. The couple went on a retreat together that rejuvenated their intimacy. They were spending more time together as a family and had plans to take their son to Disney World in the summer of 2017. During this time, someone introduced the husband to Don Richard Riso’s The Wisdom of the Enneagram. He discovered he was a “seven with an eight wing,” which, according to the Enneagram, meant he had a need for freedom.

Over the next months, his wife noticed changes in his behavior and appearance that seemed tied to his Enneagram type and its recommended path toward better inner health. Eventually, he concluded that he and his wife were not compatible.

The wife recorded in her journal that he told her, “It is possible to love someone very much, very deeply, but that person not be ‘the right person,’ ” and “if she wanted to blame something [for their separation], she should blame the Enneagram.”

Their separation and divorce were finalized shortly after their 24th anniversary.

As the stories of these two couples demonstrate, the Enneagram can powerfully influence relationships. But when does it have a positive or a negative influence? Is the Enneagram accurate? How much credence should be given to this tool?

Many psychologists have strong views on the Enneagram, ranging from the inquisitive and interested to the dismissive and disdainful. The nine-type system is growing in popularity, spawning a range of books and media in recent years, including a documentary that was slated to release in fall 2020 from best-selling author Chris Heuertz but was halted amid allegations of spiritual and psychological abuse committed by Heuertz (Zondervan also stopped promoting Heuertz’s books).

Despite the attention, many are unaware of the Enneagram’s history, purpose, or limitations. Most psychologists agree there is misalignment between pop-culture typologies and current personality science, but they have failed to communicate alternate, scientifically vetted ways for people to think about how personality functions in relation to spiritual and relational growth.

At present, there is scant empirical evidence that the Enneagram accurately describes human personality or spirituality. The nine types do not align with any scientifically evaluated models of personality.

Additionally, numerous studies show that many qualities within Enneagram types are not highly correlated (for example, being responsible does not necessarily correspond with being anxious, as The Enneagram Institute says it does for “type sixes”). Nor do those qualities tend to cluster into nine types that resemble those in the Enneagram (instead, personality psychology suggests they cluster into three or five broader profiles, depending on the model).

Several questionnaires have been created to help people discern their Enneagram type, such as the Riso-Hudson Enneagram Type Indicator, the Wagner Enneagram Personality Style Scales, and the Stanford Enneagram Discovery Inventory and Guide. However, within the Enneagram practitioner community, there is disagreement over the utility of such tools.

Some people support their use, while others maintain that finding your type is best done through a process of discernment under the guidance of a spiritual director. A handful of research studies (mostly conducted by Enneagram proponents) have attempted to test the reliability and validity of the questionnaires, but the results have largely failed to support their viability.

Many Enneagram advocates maintain that the scientific validity of the Enneagram isn’t a prerequisite for its use in spiritual growth. Learning from Augustine, however, we believe that all truth is God’s truth and empirical data about the world helps expand what can be known about God through general revelation.

First Thessalonians 5:20–21 teaches that we should not despise new prophecies or spiritual wisdom but instead should test everything and retain what is good and true. Because the Enneagram makes many claims about human nature that are scientifically testable, it merits rigorous testing because humans are part of God’s creation.

Yet without scientific evidence of its accuracy, many psychologists fear the Enneagram can propagate a false narrative about human personality. Certainly, many people do grow from Enneagram-based programs or curricula. But it’s possible that growth originates through other components in these programs, such as meaningful discussion questions and empathy-building exercises. The Enneagram model itself may not even be necessary for those mechanisms to promote growth.

Søren Kierkegaard said, “Once you label me, you negate me.” Though his statement is extreme, humankind’s natural tendencies and biases influence the ways we process information about ourselves and other people. Confirmation bias—the idea that humans notice and remember information that aligns with their preconceived ideas about themselves or others—is a phenomenon that has been thoroughly studied since it was first observed in the 1960s.

With the Enneagram, confirmation bias could mean that once people determine their type, they will notice and remember only instances where they behave in a manner congruent with their type and ignore incongruent behavior. Because one of the main activities of Enneagram programs is to identify and work on blind spots or weaknesses, some psychologists fear that these weaknesses may actually become more entrenched. As people begin to think of themselves in relation to the weaknesses of their Enneagram type, they will likely notice and remember information congruent with their weaknesses. Paradoxically, this could make their weaknesses more difficult to change.

Psychologists also warn that the Enneagram may promote stereotyping, which humans are naturally inclined to do. Once Enneagram users start to think about other people in terms of their type, their tendency to stereotype will kick in: They will interpret and predict others’ behaviors by their types. Because of confirmation bias, people will tend to notice behaviors that align with stereotypes and ignore counter-stereotypical information, making it difficult to recognize variations and changes in others’ motivations and behaviors.

Stereotyping is, of course, a risk of any personality assessment. And many Enneagram experts caution against stereotyping. But others, like Riso and Enneagram Institute partner Russ Hudson, seem to advocate using the Enneagram to interpret the behavior of others in a stereotypic fashion. In their 2003 book, they state that “understanding the Enneagram is like having a pair of special glasses that allows us to see beneath the surface of people with special clarity: We may in fact see them more clearly than they see themselves.” Statements like this trigger confirmatory bias and harmful stereotyping.

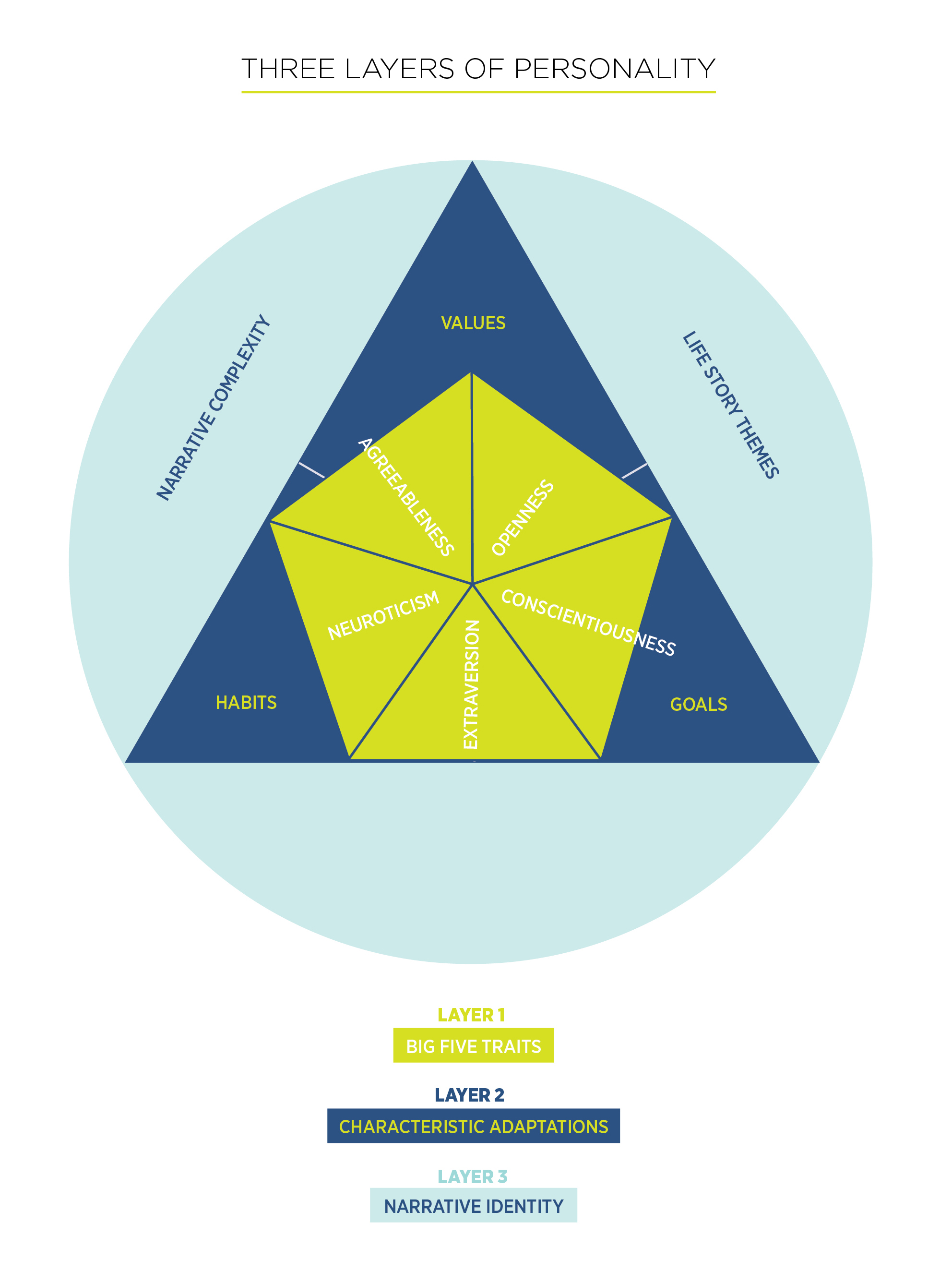

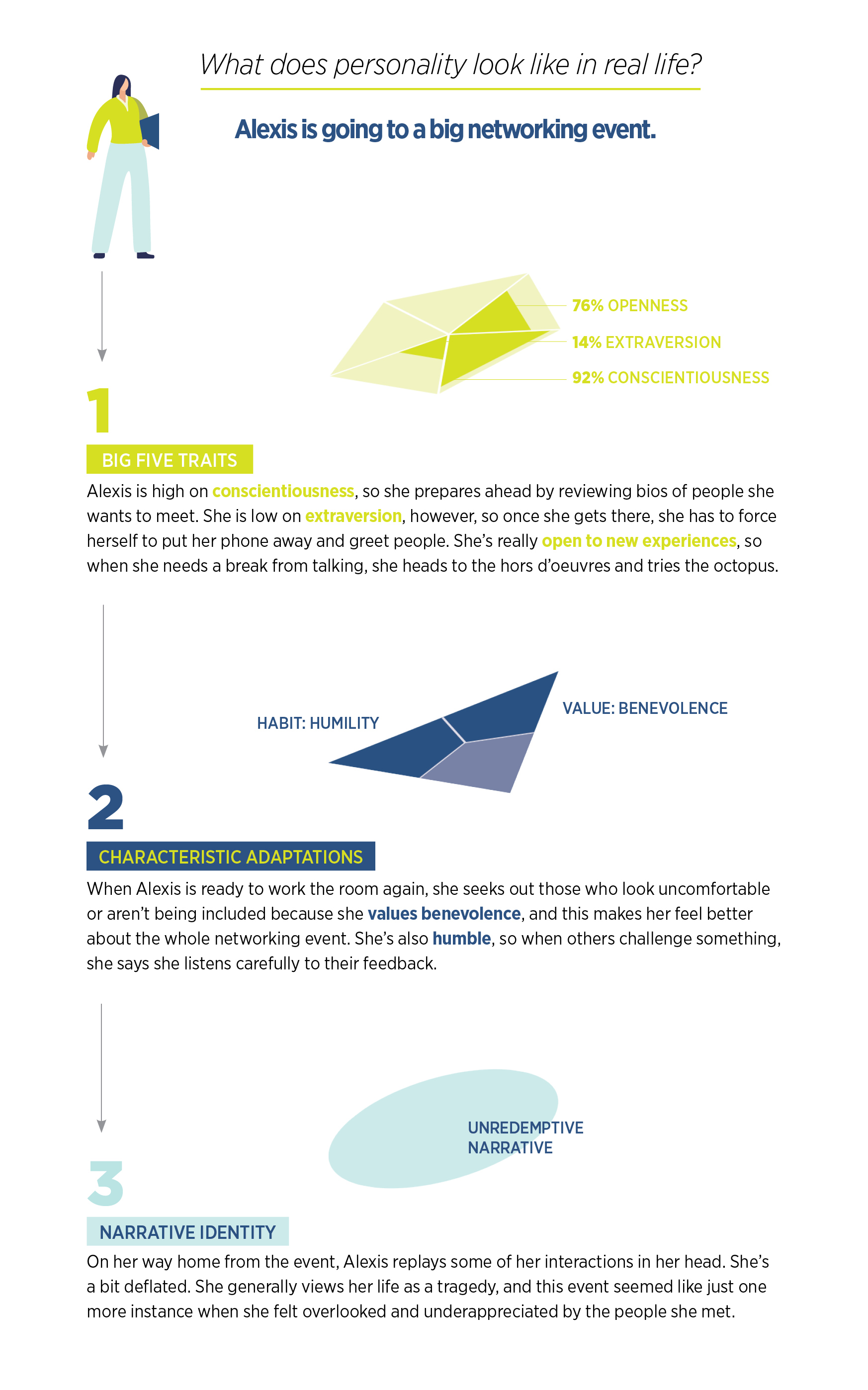

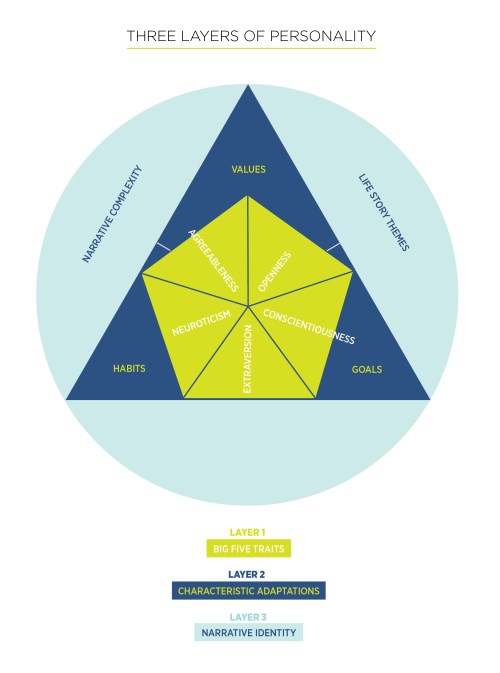

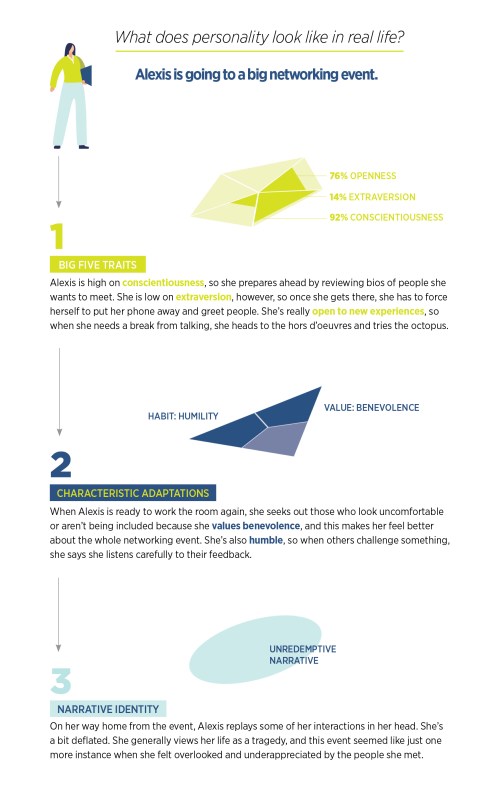

Whether or not people choose to use the Enneagram, psychological science offers other concepts that might help them better understand their personality and their relationship with God. Psychologists tend to view personality as multilayered and dimensional. Dan McAdams, a psychologist at Northwestern University and one of the world’s leading personality experts, maintains that personality is composed of three levels: personality traits; “characteristic adaptations,” the habitual ways we respond to different situations and what motivates us; and the personal stories that we tell about our individual lives.

Each level of personality provides unique information about who people are based on both genetic predispositions and interactions with their environments—that is, both nature and nurture.

Looking at top-level personality traits, scientists have demonstrated in many studies with data from millions of people across the globe that there are five consistent dimensions. Known as the “Big Five,” they are:

Extraversion, which captures a person’s warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, positive emotionality, activity, and excitement-seeking;

Neuroticism, which captures a person’s anxiety, hostility, depression, self-consciousness, impulsivity, and vulnerability;

Conscientiousness, which captures a person’s competence, order, dutifulness, achievement-striving, self-discipline, and deliberation;

Agreeableness, which captures a person’s trust, compliance, altruism, straightforwardness, modesty, and tender-mindedness; and

Openness to new experiences, which captures a person’s fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, actions, ideas, and values.

Big Five theory places each person on a continuum for every trait, recognizing that most people are somewhere in the middle for any given one.

At the second level of personality, characteristic adaptations, research done on the notion of virtues is particularly relevant for spiritual growth. Psychologists define virtues as the habits people cultivate connected to moral or spiritual motivations and identity. Whereas personality traits are quite stable, virtues can be developed through intentional activities that are practiced in relationship with God and a spiritual community.

Numerous studies support the efficacy of intentional activities to increase virtues like forgiveness, gratitude, patience, or hope. There are books, videos, and podcasts offering proven strategies to help people do just that. Likewise, several scientifically valid measures and quizzes are freely available to assess virtues, as well as the values and moral motivations that underlie them.

Finally, the stories people tell about their lives and the ways they tell those stories are often overlooked components of personality relevant for spiritual formation. In interviews with people across the United States, McAdams found that people who told their life stories using a narrative of redemption were more likely to be highly generous than people who told their life stories with other types of narratives (such as tragedy, comedy, or constant upward trajectory).

This suggests that one of the most important components of spiritual formation is constructing and reconstructing the stories of our lives and our communities to reflect the redemptive work of Christ. Christ’s story of redemption is the essence of our faith. The traditional practice of telling the stories of our own redemption through testimonies should be the foundation for spiritual growth.

Let’s return for a moment to our couples who used the Enneagram to propel change in their relationships, though with very different results.

The first pair, grappling with histories of divorce, grew individually and learned how to engage in healthy conflict. Each of them is better able to empathize with the complexities of the other’s personality. Aided by the Enneagram, they focus on God’s grace in their lives and extend this grace to each other.

In contrast, the second couple barely communicates with each other anymore, even to coordinate the custody of their son. The wife is heartbroken because of the effect the Enneagram had on their family, while the husband coldly moved on, as though he had no choice in the longevity of his marriage.

We cannot objectively determine whether the Enneagram truly played a causal role in the formation and dissolution of these relationships, or whether the outcomes would have been the same without its influence. But there is no doubt that these couples view the personality tool as determinative.

What, then, are we to make of both the scientific evidence and the compelling stories of real-life growth and harm? First, we can affirm that it is right and good for believers to seek out tools and opportunities to grow in their relationship with God and become more self-aware. But Enneagram enthusiasts or explorers should be cautious when using a tool that has yet to withstand scientific scrutiny, and they should never use the Enneagram types to stereotype others.

Instead, we can all employ some of the evidence-based tools from psychological science that can help us understand our basic personality traits, develop virtuous habits, and narrate Christ’s redemptive work in our lives and our spiritual formation.

Sarah A. Schnitker is a personality and social psychologist at Baylor University. Jay Medenwaldt is pursuing a PhD in social psychology at Baylor. Lizzy Davis, a grant manager at Baylor, has used the Enneagram both personally and professionally.