When we were children, my brother and I loved reading National Geographic. We absorbed new issues as soon as they arrived. We also sought out older issues, buying stacks at garage sales until our collection spanned many decades.

Reading National Geographic was like staring at the stars. It reminded us how wondrously small we are. Its blazing images expanded our vision of the startling enormity of the planet, the fecundity of creation, and the diversity of human life. Its stories made clear that our own experience was a tiny fragment in a vaster and more mysterious reality.

It was a humbling recognition, but one that stirred a holy longing. To rise up on our feet, leave the still air of our indoor lives, and go. To wander and explore. To measure ourselves against the horizons of the world. To test our nerve against its dangers. To confront ourselves with ways of being in the world radically unlike any we knew. And to return changed. Wiser and hardier. More capacious. Containing more of the world within our rib cages.

Our prayer is that the issue you hold in your hands will have a similar effect. That it will transport you to far-flung corners of the globe and expand your imagination of what it might mean to follow Jesus. That it will show you the immensity and the beauty of the body of Christ. And that it will stir in all of us that same sacred yearning to go beyond ourselves, outside ourselves, and plunge into the life of a kingdom that knows no boundaries and never ends.

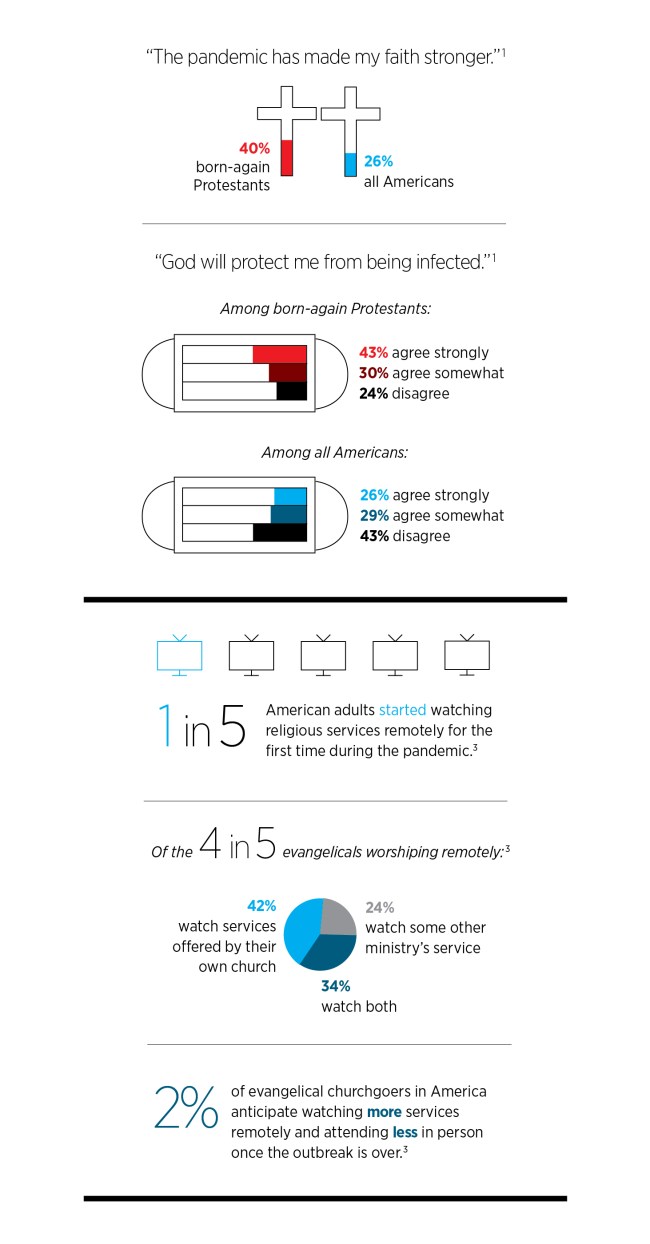

We stand near the close of a profoundly painful year. A global pandemic has brought death and devastation on a colossal scale. Racial and political tensions have torn apart our families, our churches, and our country. We find ourselves disappointed in our leaders, disillusioned with our institutions, and divided against our brothers and sisters.

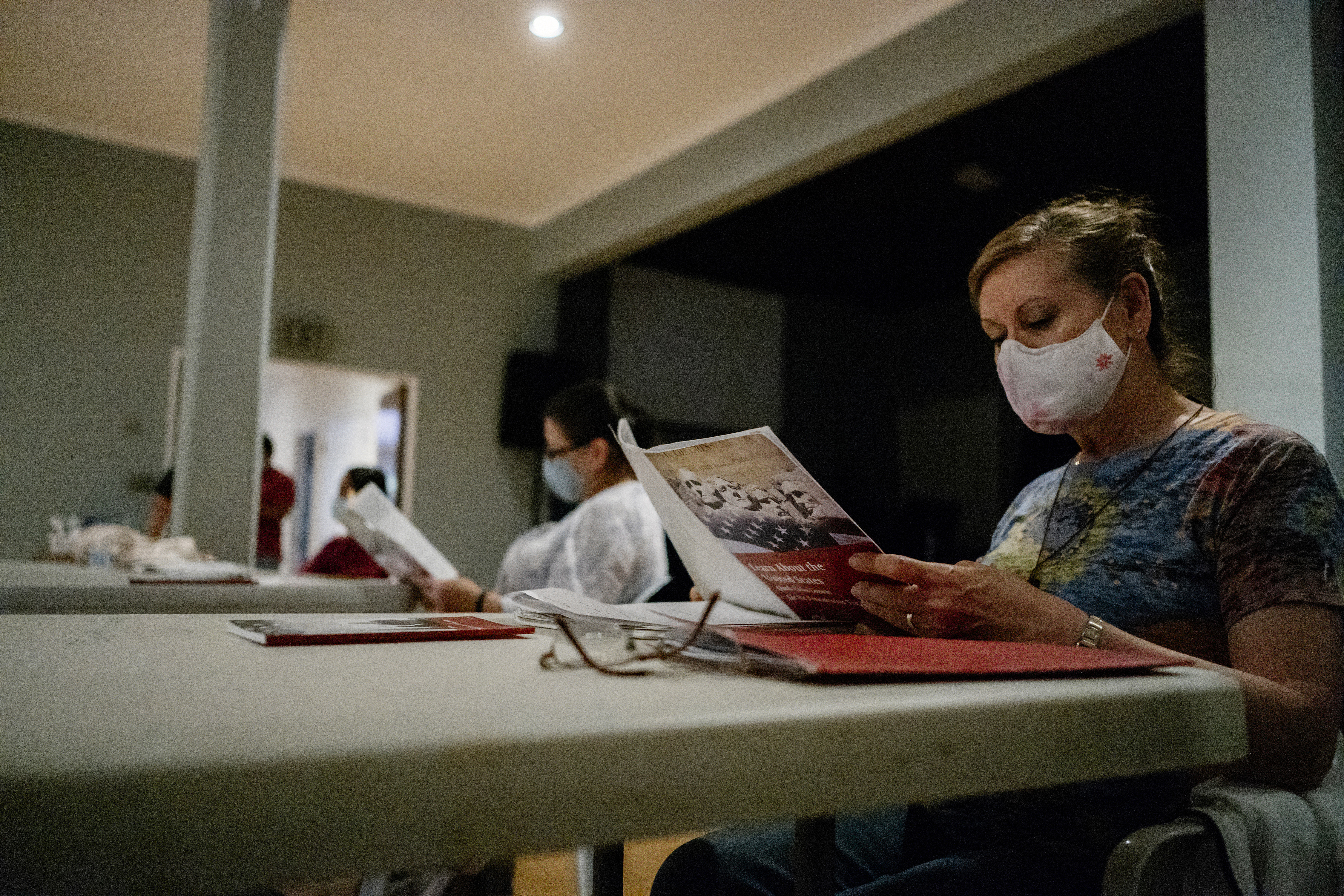

Which is why it’s so essential to tell stories like the ones in these pages. When loneliness and destruction seem to have carried the day, we remember God is with us. His eye has not left the birds of the air or the flowers of the fields, much less the children of his hand. Jesus still walks among the orchards of central California, in the shantytowns of Kenya, on the mountain paths of Papua, and in the corridors of a Mercy Ship on the African coast, seeking the lost and serving the least through the feet and the hands of those who answer his call.

The world rushes in to tell stories of Christians behaving in a manner unworthy of their calling. Those stories are important, and we do well to reflect on them and give thanks for God’s grace. But just as important are stories of the selfless men and women of the kingdom of God, people in all professions in our own communities and all around the globe who follow the call of Christ in ways that are redemptive, sacrificial, and unimpeachably good.

In fact, the impact of these stories should be greater than the impact of those National Geographic issues I consumed as a child. For these are not stories of mere creation and culture. They are stories of the Creator. There are no real heroes in the kingdom of God—or there is only one, the Christ, who lives and moves within us, who brings light into darkness and life into death. So as we read these stories, we give thanks not only for the vessels who are humble bearers of Christ to a world in need but also for the one who stirs and strengthens them—and us—to do the work of the kingdom.

Consider this issue a glimpse of where CT is headed. The stories and ideas of the kingdom of God can renew the church and transform the world. So we elevate the storytellers and sages of the global church. We offer beautiful storytelling and biblical wisdom. And we hope through our work to see the church become even more beautiful than it already is, and an even more powerful witness.

An already difficult year is growing dark and cold. But as we like to say this time of year, “The people walking in darkness have seen a great light” (Isa. 9:2). The church is still his bride, and God still loves the world.

Timothy Dalrymple is president and CEO of Christianity Today. Follow him on Twitter @TimDalrymple_.