As India continues its attempt at the world’s biggest social isolation effort to halt the new coronavirus outbreak, millions are struggling to navigate weeks of canceled public transit, closed businesses, and therefore no Sunday services.

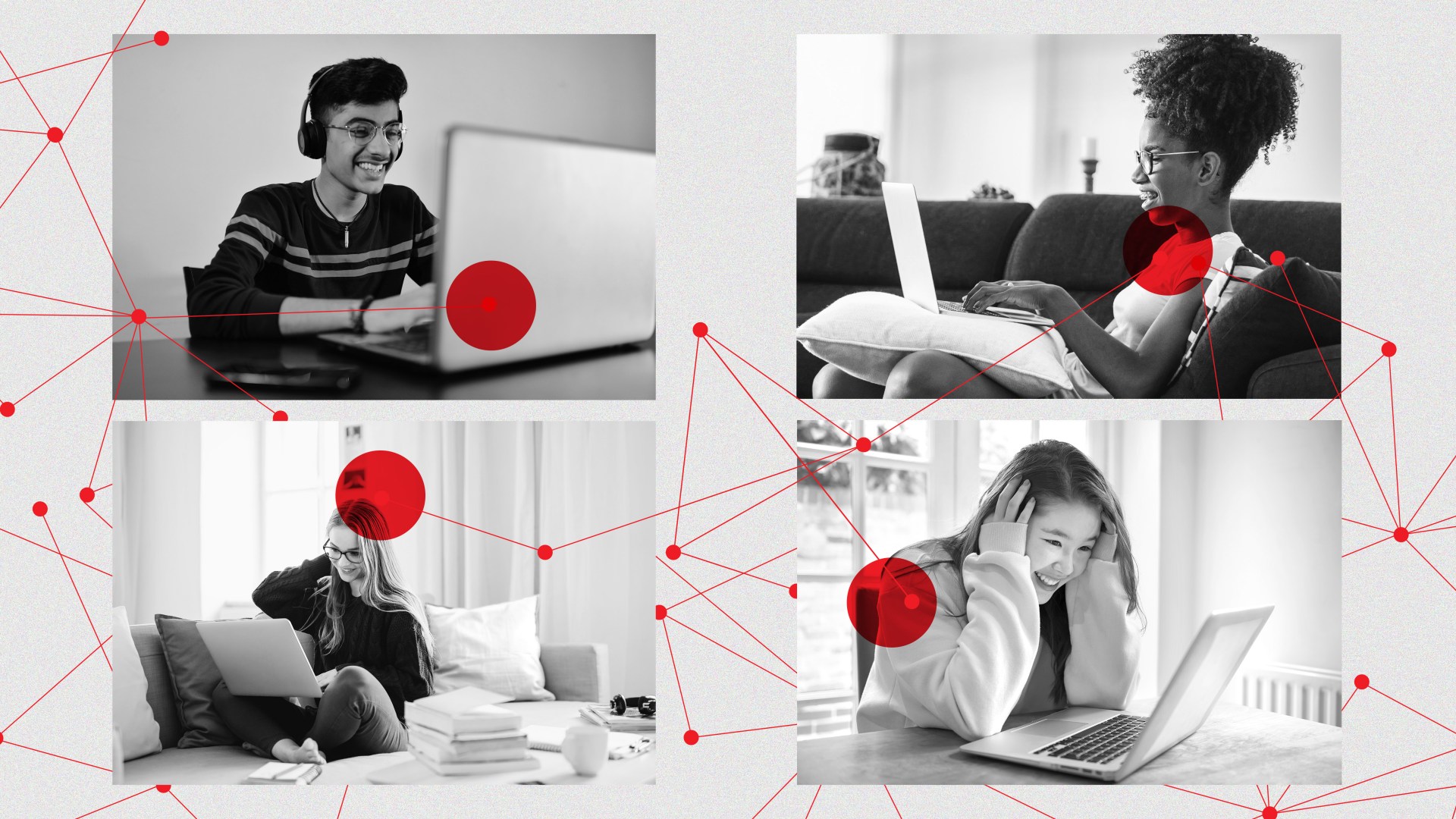

Many smaller churches have their attendees join the livestreams of larger churches. Our own sunrise service on Easter, conducted on Zoom, drew 250 people—despite its 5 a.m. start.

After greeting Christians and praising “Lord Christ” in Good Friday and Easter tweets, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced this week his decision to extend the lockdown until May 3, due to the lack of widespread testing for the virus as the death toll rises.

However, despite all the disruption and our inability to worship together as usual, I believe the pandemic lockdown is being used by God to use his church in a new way.

Two things were happening before the pandemic hit. First, the church was severely opposed. Second, because of this opposition, there has been a prayer movement that resulted in great unity among the national Christian community. Churches have begun to overlook their historical denominational divisions, bringing the Indian church to the cusp of revival. There has been news of breakthroughs in the work of the Holy Spirit in places and among people. And in spite of severe opposition, the church has been responding maturely and collectively to its challenges. As a result, the church has been growing spiritually and numerically.

Church leaders across denominations have fostered a misperception in the pews—and in the watching world—that Christians concentrate their efforts solely on Sunday gatherings. Commitment to the church and its goals has been gauged by Sunday morning attendance. Thus, at the initial stages of the pandemic, only a very small portion of churches in India were responding practically to the upcoming challenges.

Following the lockdown, churches began scrambling to put plans together. I asked one congregation how they planned to hold their services, and their response was rather naïve. They said that churches cannot close their doors, believing that the Bible mandates weekly group worship in buildings and that God grants health to the faithful. Because of this general attitude, it took three weeks for many churches to get their feet under them and to provide online alternatives.

When churches started streaming their services online, they were surprised at the audience they received. I know of small churches that normally had less than 100 people attend on an average Sunday now have more than 700 viewers online. Our own church, Bible Bhavan Christian Fellowship, which has been livestreaming for more than four years, saw a 300 percent increase in viewership. People have been watching from all over India, and all around the world. We have received responses from as far as Africa and South America.

Indian churches have been praying for the Lord to enlarge their borders, and the Lord has answered with an unexpected opportunity to reach more people.

The challenge that churches now face is harnessing this new reach and developing tools for follow-up and discipleship in a new teaching model. For example, our midweek ministries have taken on a life of their own as physical attendance is no longer a criteria. Our groups for men, women, youth, and pastoral care have more participants and from farther away, which is good because we are ministering to many more people. While we had to close our Bible schools in seven locations, we are moving our complete syllabus from written materials to audio, visual, and digital versions. We were too busy doing the Lord’s work to think of this before, and we may have missed the bus on such innovations if the lockdown had not happened.

As churches deal with the reality of increased community needs—since many people are unable to perform their jobs during the lockdown—they face complicated decisions. In the past, many churches were apprehensive when responding to the poor, since they could be accused of having an ulterior motive to convert those they were serving. Many churches also did not have adequate resources or tools to help their non-Christian neighbors who had no interest in the church.

Now, I have heard amazing stories from our multisite congregations across North India where neighbors who once were hostile toward us have come forward and supplied the church with free food and aid to distribute to vulnerable community members. At one of our churches, the neighbors even volunteered to come with our team to provide aid to the community, and shared that it came from the local church.

As the Indian church is expressing its love for those who are suffering the most, previously antagonistic neighbors are partnering with the church in our expressions of help. This marks a new day.

For example: I know a local church community in rural North India that has been struggling even in the best of times. Despite showing genuine love and concern for the community around them, they have continually faced opposition and threats. After COVID-19 hit India and a nationwide lockdown was put in place, the local police showed up at the doors of the church. The pastor was apprehensive. The police brought a request from the government for the church to make 1,000 cloth face masks in its center to be distributed among the community. The officers then accompanied the pastor to a local cloth shop, specially opened for them to procure the necessary materials.

What the police did not know was that this church community had been praying for ways to respond during the lockdown. The Lord answered by providing an opening to serve and the potential for better relationships with the authorities.

Finally, a common refrain being heard in all Indian churches and denominations is to repent. Even in our conservative Indian culture where sins are not openly confessed, people are being more transparent. The church is repenting of its own sins, the sins of the city, and the sins of the nation. We pray this prayer regularly: “Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

The world we will come back to after this pandemic will look very different. Therefore, the church’s priorities must turn from looking inward to looking outward.

I believe the church has been ushered into a new age of growth and engagement with each other and with the world around us. We are witnessing a huge turning after God. The last revival in India was in 1905-1906. If all the nations of the world repent, then we can anticipate a mighty movement from God in our times.

Isaac Shaw is senior pastor of Bible Bhavan Christian Fellowship.

"Speaking Out" is Christianity Today's guest opinion column and (unlike an editorial) does not necessarily represent the opinion of the publication.