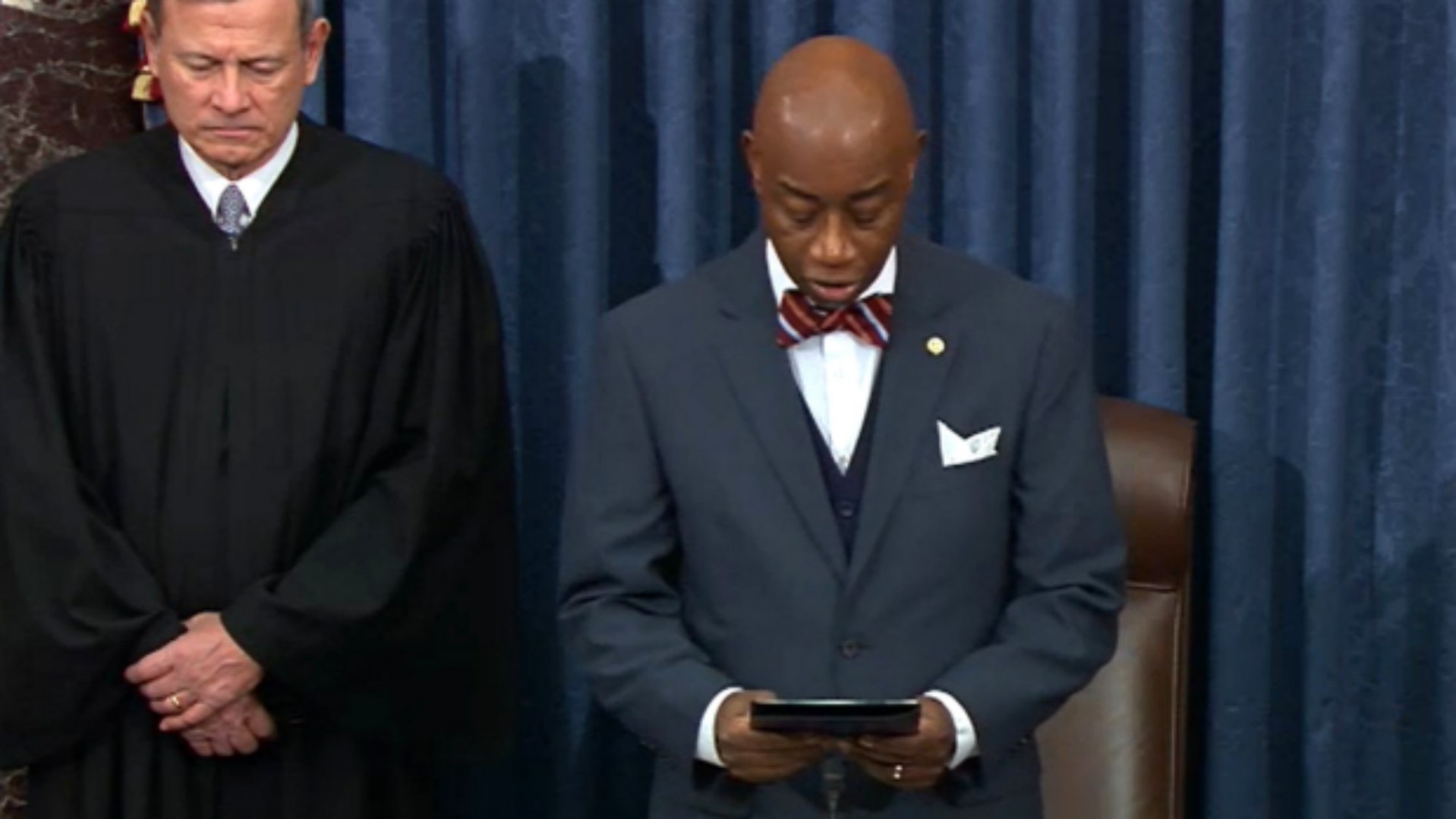

While elected officials from either party don’t agree on the outcome of the impeachment trial, they could agree on how to pray for the proceedings, according to Barry Black, a Seventh-day Adventist minister and the longtime chaplain of the US Senate.

So what do you pray after the US Senate votes to acquit Trump on two articles of impeachment, as it did on Wednesday afternoon?

You pray that God’s will be done.

“I think the prayer of Jesus in Gethsemane provides us with the model,” Black told CT. “The preamble to saying, ‘Let your will be done’ can be ‘Father, all things are possible for you. If it is possible, let the impeachment trial come out this way, nevertheless, not as I will but let your will be done.’ That’s the basic setup, but the dominant thematic focus should always be ‘Let your will be done.’”

The minister, with his signature bow tie and deep preacher’s cadence, says that in the middle of the polarization and partisan sniping, he has urged senators and staff on both sides to seek God’s will.

People have been listening closely to Black’s prayers as the Senate has battled over the historic impeachment vote. He draws powerful phrases from his daily devotions and hours of scriptural studies.

Before a full chamber of lawmakers, Black prayed the senators might be “bold as lions” one morning. Another, he pled for of “moral discernment to be used for your glory.” And one line last week caught a lot of attention: “They can’t ignore you and get away with it,” he said, “for we always reap what we sow.”

The Senate voted mostly along party lines to acquit the president, rejecting the abuse of power charge 52 to 48, and the obstruction of Congress charge 53 to 47. Only Senator Mitt Romney, the Republican from Utah, broke ranks, voting to convict Trump on abuse of power. Romney, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, said his religious convictions required him to stand alone.

“I support a great deal of what the president has done,” Romney said. “I have voted with him 80 percent of the time. But my promise before God to apply impartial justice required that I put my personal feelings and biases aside.”

Throughout the intense and contentious month-long process, Black has been encouraged by what he sees from people of faith behind the scenes.

“I made a statement in one of my prayers that we needed to appreciate the fact that there are patriots on both sides of the aisle,” he said. “I think they’re aware of that, and where they may have different presuppositions regarding how government best serves the people, they still respect the fact that the other side has valid concerns and valid approaches as well.”

Black is convinced that God is in charge, and God’s will is being done in the Senate. He pointed out that during the impeachment proceedings, prayer breakfasts and Bible studies continued as usual. If a united, bipartisan submission to God’s will seems unlikely in a heated political moment, things look different when officials join hands in private to pray.

“I see God at work in the fact that every week senators come together for a prayer breakfast,” the chaplain said. “I see God at work when I see every week senators coming to a Bible study, again both sides of the aisle. … As chaotic as things may seem sometimes, I see God at work in the level of civility that we somehow seem to manage in spite of how polarized our nation is.”

Now that God has brought the impeachment trial to a conclusion, Black will continue his ministry of prayer—first at Thursday morning’s annual National Prayer Breakfast, and then at a special service of praise and thanksgiving that the chaplain’s office schedules after challenging periods like government shutdowns, presidential elections, or, now, a divisive impeachment trial.

“We have wall-to-wall people who come to thank God,” Black said, “not that what they desired happened, but that his will has been done. And the expressions of gratitude emanate from that knowledge: You answered our prayer because our prayer was ‘Let your will be done.’”