They are well dressed, and most are professional people. These members of a house church in suburban San José, Costa Rica, sang some choruses, then moved into Bible study, and concluded with a sharing of prayer needs. Afterwards, many stayed around to discuss the movie, The Late Great Planet Earth, over sandwiches and chocolate cake in one of the group’s periodic “film forums.”

The attenders look and talk like North American evangelicals, but the group leader explains something that might break that mold. While most come from conservative and Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship backgrounds, he explains, “it might come as a surprise to you that probably all of these people would vote for Marxist candidates in the Costa Rican elections.”

It is becoming increasingly difficult to put Latin American Christians into North American boxes. In fact, most Latin American Christians say one shouldn’t even try.

The frequently heard criticism of the church to the north is that Christians here too often judge and criticize without bothering to listen to their Latino brothers, while at the same time they are painfully ignorant of the Latin American culture and church.

Latin America Biblical Seminary professor Richard Foulkes explains, “Sometimes people from North America will just have to sit back and listen.”

Many Latin American Christians are asking how to live scriptural Christianity in difficult living situations—in countries that may have oppressive governments or thousands of poor with no chance of bettering themselves. The answers they are coming up with sometimes appear radical to those persons who, for instance, believe that the U.S. democratic and capitalist system is God-ordained, and that if it works in the U.S., it has to work in Latin America and anywhere else.

In El Salvador, an estimated 5 percent of the population own 80 percent of the land Even in Costa Rica, the most stable and affluent Central American republic, roughly 65 percent of the wage earners make less than $100 per month. In examining the options for improving such conditions, one prominent U.S. evangelical leader and long-time worker in Latin America commented, “It would be almost impossible for a U.S. missionary to work in Latin America and not become favorable toward socialism.”

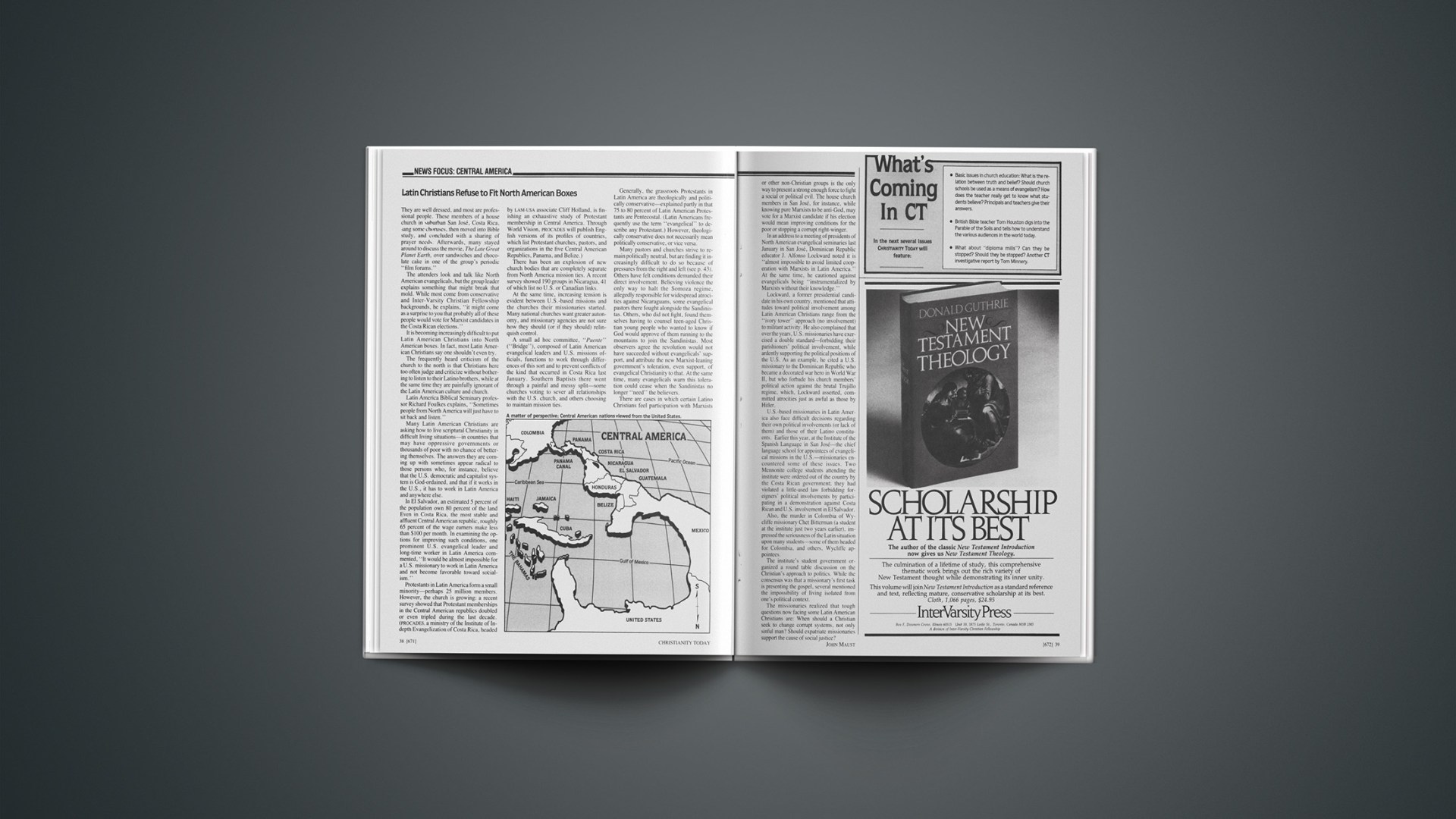

Protestants in Latin America form a small minority—perhaps 25 million members. However, the church is growing: a recent survey showed that Protestant memberships in the Central American republics doubled or even tripled during the last decade. (PROCADES, a ministry of the Institute of In-depth Evangelization of Costa Rica, headed by LAM-USA associate Cliff Holland, is finishing an exhaustive study of Protestant membership in Central America. Through World Vision, PROCADES will publish English versions of its profiles of countries, which list Protestant churches, pastors, and organizations in the five Central American Republics, Panama, and Belize.)

There has been an explosion of new church bodies that are completely separate from North America mission ties. A recent survey showed 190 groups in Nicaragua, 41 of which list no U. S. or Canadian links.

At the same time, increasing tension is evident between U.S.-based missions and the churches their missionaries started. Many national churches want greater autonomy, and missionary agencies are not sure how they should (or if they should) relinquish control.

A small ad hoc committee, “Puente” (“Bridge”), composed of Latin American evangelical leaders and U.S. missions officials, functions to work through differences of this sort and to prevent conflicts of the kind that occurred in Costa Rica last January. Southern Baptists there went through a painful and messy split—some churches voting to sever all relationships with the U.S. church, and others choosing to maintain mission ties.

Generally, the grassroots Protestants in Latin America are theologically and politically conservative—explained partly in that 75 to 80 percent of Latin American Protestants are Pentecostal. (Latin Americans frequently use the term “evangelical” to describe any Protestant.) However, theologically conservative does not necessarily mean politically conservative, or vice versa.

Many pastors and churches strive to remain politically neutral, but are finding it increasingly difficult to do so because of pressures from the right and left (see p. 43). Others have felt conditions demanded their direct involvement. Believing violence the only way to halt the Somoza regime, allegedly responsible for widespread atrocities against Nicaraguans, some evangelical pastors there fought alongside the Sandinistas. Others, who did not fight, found themselves having to counsel teen-aged Christian young people who wanted to know if God would approve of them running to the mountains to join the Sandinistas. Most observers agree the revolution would not have succeeded without evangelicals’ support, and attribute the new Marxist-leaning government’s toleration, even support, of evangelical Christianity to that. At the same time, many evangelicals warn this toleration could cease when the Sandinistas no longer “need” the believers.

There are cases in which certain Latino Christians feel participation with Marxists or other non-Christian groups is the only way to present a strong enough force to fight a social or political evil. The house church members in San José, for instance, while knowing pure Marxists to be anti-God, may vote for a Marxist candidate if his election would mean improving conditions for the poor or stopping a corrupt right-winger.

In an address to a meeting of presidents of North American evangelical seminaries last January in San José, Dominican Republic educator J. Alfonso Lockward noted it is “almost impossible to avoid limited cooperation with Marxists in Latin America.” At the same time, he cautioned against evangelicals being “instrumentalized by Marxists without their knowledge.”

Lockward, a former presidential candidate in his own country, mentioned that attitudes toward political involvement among Latin American Christians range from the “ivory tower” approach (no involvement) to militant activity. He also complained that over the years, U.S. missionaries have exercised a double standard—forbidding their parishioners’ political involvement, while ardently supporting the political positions of the U.S. As an example, he cited a U.S. missionary to the Dominican Republic who became a decorated war hero in World War II, but who forbade his church members’ political action against the brutal Trujillo regime, which, Lockward asserted, committed atrocities just as awful as those by Hitler.

U.S.-based missionaries in Latin America also face difficult decisions regarding their own political involvements (or lack of them) and those of their Latino constituents. Earlier this year, at the Institute of the Spanish Language in San José—the chief language school for appointees of evangelical missions in the U.S.—missionaries encountered some of these issues. Two Mennonite college students attending the institute were ordered out of the country by the Costa Rican government; they had violated a little-used law forbidding foreigners’ political involvements by participating in a demonstration against Costa Rican and U.S. involvement in El Salvador.

Also, the murder in Colombia of Wycliffe missionary Chet Bitterman (a student at the institute just two years earlier), impressed the seriousness of the Latin situation upon many students—some of them headed for Colombia, and others, Wycliffe appointees.

The institute’s student government organized a round table discussion on the Christian’s approach to politics. While the consensus was that a missionary’s first task is presenting the gospel, several mentioned the impossibility of living isolated from one’s political context.

The missionaries realized that tough questions now facing some Latin American Christians are: When should a Christian seek to change corrupt systems, not only sinful man? Should expatriate missionaries support the cause of social justice?