What does Western Christianity have to learn from a Hindu who learned so much from Christ?

The first part of this essay surveyed representative events in the life of Mohandas K. Gandhi that illumine his pilgrimage (CT, April 8, p. 12). Yet biographies of this strange man do not apply in the same way they do to other towering historical figures; too much of Gandhi’s life was an internal development for which external events had little relevance. His own autobiography, Gandhi, reveals this clearly. The history is there, somewhere, buried in scant allusions and references to events and places.

But the book presents history only in the same sense in which Psalms offers a history of King David. Psalms, too, contains history, and if you decipher individual ones you can come up with basic facts about King Saul’s chases, about David’s adultery and his reign, and Israel’s civil war. Yet the external events merely form the background for the far more prominent leitmotif of a soul struggling and communing with his maker.

So too, Gandhi’s autobiography presents events in a strange proportion. Maybe one paragraph will mention the Great Salt March, a turning point in Gandhi’s career and India’s history, but four consecutive chapters will explore Gandhi’s internal agony on whether or not goat’s milk should be included in his vegetarian dictum against dairy products. Gandhi portrays his life as a straight-line progression, a gradual honing of the soul. “The Story of My Experiments with Truth” he subtitled it, presenting the events of his life as merely the stage on which the internal strength of his own character is being played out. What matters most is the spiritual warfare inside.

Much of Gandhi’s life seems baffling, alien, and incomprehensible to the average Westerner. And yet Gandhi insisted with his prescient voice that civilization must look to the East and not to the West for its ultimate solutions. The Christian church, birthed in the East but formulated and structured in the West, shares many of the crises of Western civilization as a whole.

For perspective, perhaps we need to step back and listen to this enigmatic figure who, although not a Christian, adapted many Christian principles to a modern context. Christian saints before him had followed these same beliefs, but we have grown so accustomed to our Christian saints that we no longer hear their message clearly. When a sound is too loud, sometimes we can discern it better in its echo.

From Gandhi’s autobiography and books about him, I have extracted principles that seem to me to have acute relevance to the Western church. Now, for the first time, more nonwhites than whites call themselves Christians. The center of the church is moving to Africa and Asia. Whether we can comprehend, appreciate, and to some extent embrace these principles may determine how successfully we can meet the challenge thrown to us by the East. It may, in fact, determine our planetary survival.

Simplicity

Gandhi came to symbolize this virtue more effectively than any man in history. He had tried Western ways once, as a law student in London when he outfitted himself in an evening suit, silk top hat, patent-leather boots, white gloves, and a silver-tipped walking stick. He held on to Western dress and was something of a dandy when he returned to India. But he spent his twenties and thirties working as a lawyer in South Africa, and there the guiding principles of his life began to coalesce.

First Gandhi began to iron the collars of his own shirts, much to the ridicule of his law colleagues. Then he practiced cutting his own hair, leaving patches of unevenness that drew even more laughter. Although drawing a fat salary of 5,000 pounds a year, he experimented by halving household expenses, then halving them again. (At the end of every day he made meticulous accounting of every penny spent.) He found that the process of spending less money and acquiring fewer possessions vastly simplified his life and gave him an inner peace. In addition, it allowed him more completely to identify with the poor people he often represented.

Gandhi had fought vigorously for the right to travel first-class on South Africa’s railways ever since one critical incident, when he was thrown off a train because of skin color despite possessing a first-class ticket. Yet voluntarily Gandhi began to travel third-class. In India, where third-class travel combines crowds, noise, filth, and smells in an experience unimaginable to most Westerners, Gandhi continued the practice. He got little rest sitting bolt upright, squeezed into the wooden-slat railway benches, but he rejected overtures to upgrade.

Gandhi’s autobiography devotes whole chapters to his lifelong process of refining eating habits. He broadened his vegetarianism to exclude eggs and milk. Gradually he began eliminating salt, spices, tea, and most exotic vegetables and fruits. Finally he took a vow to partake of only two meals a day, never after sunset, and to consume a maximum of five different items a day, including medicines. A typical meal consisted of two segments of grapefruit, some goat’s curds, and lemon soup.

After Gandhi renounced material possessions he carried all his belongings in a single sack. To answer correspondence he used pads made from the cutup envelopes of the letters he was answering. He ate with a spoon that had been broken off and repaired with a piece of bamboo lashed to it with string.

Ironically, the impetus for all this emphasis on simplicity came not from a Hindu holy man, but from two books by Westerners, The Kingdom of God Is Within You by Tolstoy, and Unto This Last by John Ruskin, as well as some of Thoreau’s essays. Those authors convinced him that riches were a trammel, and that only the life of labor was worth living.

Gandhi maintained his simple, uninterrupted routine even after he became one of the most famous people in the world. If anything, he grew even more strict, keeping to his daily schedule and diet whether in the viceroy’s palace or Calcutta’s sweepers’ colony. He also observed every Monday as a day of silence, both to rest his vocal cords and to promote harmony in his inner being. He held to that silence even when summoned by Lord Mountbatten in the heat of intensive negotiations on India’s future.

Today the American church, set in the midst of the most technologically complex society in history, is hearing calls for return to simplicity. Voices like those of Richard Foster, Ron Sider, and the editors of Sojourners and The Other Side uphold the virtues of simple lifestyle and raise questions about the morality of American standards in the light of world inequities (though, in fairness, the level of simplicity they recommend more closely resembles what Gandhi started with than what he later attained). I will leave the subjective issue of lifestyle to others more confident than I. Gandhi’s unique contribution on lifestyle centers in the reason for simplicity, not the level of simplicity. For Gandhi, simplicity was motivated not so much by guilt or a comparison with others but rather by the salubrious effect it could have on the leader himself.

Gandhi had dined with great leaders. He had seen the seduction of power, the reliance on servants to carry out every whim, the endless spiral staircase of luxury, the absorbing anxiety over investments, the deluge of letters and speaking invitations and endorsements and phone calls. Knowing well the burden of fame, he also knew the only way to combat it was to seek simplicity with all his heart. If he did not, his soul force, the inner strength from which he got all his stamina and courage for spiritual confrontations, would leak away.

From the inside, I have watched a disturbing pattern in what we do to our Christian leaders. We reward them with applause, fame, enticing new contracts, and a flurry of requests for speaking engagements and radio and television appearances and publicity tours. We insist that the spiritual leaders of our organizations become experts in management while carrying a crushing load of personal appearances. We push our pastors to function as psychotherapists, orators, priests, and chief executive officers. When a leader shows special acumen, we tempt him or her with radio shows, a TV series, and of course, a massive direct-mail machine to keep the organization’s superstructure intact. In short, we in the church slavishly copy the secular model of media hype and corporate growth.

I wonder how much more effective our spiritual leaders would be if we granted all of them Monday as a day of silence for reflection, meditation, and personal study. I cannot imagine a leader’s business manager—or, for that matter, constituency—permitting such a frivolous plan. Of course, daily demands are pressing, but were not those of Gandhi, leader of the second most populous country on earth?

Human Dignity

Part one of this essay summarized the revolutionary impact Gandhi had on a 5,000-year-old tradition of caste consciousness. In a momentous stroke, he renamed Untouchables the Harijans, or Children of God, and then risked his entire career by inviting them to live with him on his commune. Gandhi devoted his life to recognizing the inherent dignity in every human being. He strove to devote the same attention to making a mud pack for a leprosy victim as to conducting an interview with the viceroy of India. Along the way, he helped elevate the status of women in the country by surrounding himself with highly competent women followers.

Gandhi summarizes his beliefs in three points, which he credits to John Ruskin’s book Unto This Last:

1. That the good of the individual is contained in the good of all.

2. That the barber’s work has the same value as a lawyer’s inasmuch as all have the same right of earning their livelihood from their work.

3. That a life of labor, that is, the life of the tiller of the soil and the handicraftsman, is the life worth living.

Those principles transformed Gandhi’s life, and he sought out ways to inculcate them. In cities such as Bombay and Calcutta, he preferred the hovel of a sweeper’s colony to a hotel. He used a pencil until it was reduced to an ungrippable stub out of respect for the human being who made that pencil.

In a sense the Christian church has led the way in this principle of human dignity. Missions movements have responded to the downtrodden, such as those with leprosy and the underclass, more quickly and often more effectively than governments. But we in the West are still learning the difference between charity, which we’re good at, and changing a person’s self-perception, which we’re not. Evangelicals (with notable exceptions among Catholics and Pentecostals) have been notoriously deficient in communicating a sense of dignity to the blue-collar worker and the unemployed.

Too often our motives smack of paternalism (so do the words: downtrodden, underclass). I, the educated, healthy, wealthy American, reach out in compassion to help you improve yourself. We see ourselves as on the side of Christ, giving in love to the needy. But Matthew 25 makes it quite clear that Jesus is on the side of the poor, and we serve best by elevating the downtrodden to the place of Jesus. Charity is not condescending, but rather ascending—we have an opportunity to serve someone far better. Somehow Gandhi communicated that spirit to those whose lives he touched; he made even the Untouchables feel like favored Children of God.

Self-Discipline

In his personal habits Gandhi moved far beyond self-discipline into renunciation. He held up the Hindu/Buddhist ideal of passionlessness that has generally been rejected by Christian orthodoxy, save for a few ascetic movements. He allowed no room for sensuous pleasures, and in his autobiography you read nothing of a pleasant experience with music or with nature or sensory pleasures of taste or smell.

You do read, however, of his lifelong struggle to stamp out the residue of human passion. At the age of 37, after a 24-year struggle against lust for his wife (yes, he was married at 13), he took a solemn vow of celibacy. He spent much energy investigating what foods might have the slightest aphrodisiac quality, concluding that milk of any kind, salt, and certain fruits contribute to sexual urges. For 30 years he managed to avoid having an erection, with the exception of one night when he awoke from a dream. He called that night “my darkest hour” and immediately took a six-week vow of silence to atone for it.

Applying the same rigid standards of restraint in his speech and emotions, Gandhi sought to suppress any sign of anger, violence, and hatred. This tendency, of course, totally contradicts the stream of development recommended by modern psychology. Commenting on similar trends in Christian saints, Jurgen Moltmann has observed that “what are virtues for the mystic are torment and sickness for the modern man or woman: estrangement, loneliness, silence, solitude, inner emptiness, deprivation, poverty, not-knowing, and so forth.… What the monks sought for in order to find God, modern men and women fly from as if it were the devil.”

By citing these instances of ascesis I do not mean to hold them up for us to emulate. Yet one fact intrigues me. Gandhi’s variety of discipline seeped into the consciousness of his nation and is still revered in India today. America has a parallel in legalistic fundamentalism with its strictures against premarital touching, makeup, smoking, drinking, modern music, and sometimes even bowling and roller skating, counterbalanced by its emphasis on personal devotion and discipline. Yet in recent years that fundamentalism has tended to spawn a generation with a great distaste for discipline. Richard Quebedeaux coined the term “worldly evangelicals” to describe those who seem religiously to explore the limits of grace by trying all the habits that were anathema to their parents. What makes Gandhi’s ascesis mystically attractive to some of these same young people when the self-discipline of fundamentalism repels them?

Could it be that the difference in appeal lies not so much with the specifics of the discipline—what is given up—as with the motive for it? In fundamentalism, restraint, care for health, sexual control, temperance of vices—wise principles all—usually come interlarded with guilt and motivated by a desire for moral superiority. Gandhi’s regimen, though far more strict (I haven’t met a Bob Jones graduate yet with a Gandhian diet or lifestyle) derived from his personal search for peace. Discipline opened doors of freedom, it did not close them, he said. The right action brings peace, and he sought to eliminate any possible diversion from that peace “not as this world giveth.”

It is for my sake, explained Gandhi, that I insist on such Spartan practices. I am the one who will suffer if I give in to my carnal nature, and I am the one who will profit from whatever artificial controls I can erect around it. Fear of internal destruction and a desire for wholeness just may be more effective motivators than fear of punishment.

Sadly, the concepts of grace and forgiveness from God do not appear in Gandhi’s works; Hinduism stumbles at grace. (“If one is to find salvation,” said Gandhi, “he must have as much patience as a man who sits by the seaside and with a straw picks up a single drop of water, transfers it and thus empties the ocean.”) He contributed a legalism without judgment, yes, but a legalism nonetheless.

The East has a rich legacy of holy men, culminating in the Buddha who came to personify control over human passions. An ascetic in the East is not pitied, or laughed at, or made to feel a martyr, as often happens in the West, but rather admired for having achieved a deeper plane of existence. Discipline has lost its appeal for us in the West. Is it possible to recover some of that implicit value in self-discipline without also pulling in the concomitant reliance on works rather than grace? One cannot deny that the “soul force” of Gandhi’s leadership radiated power because of his unimpeachable personal example. Could anyone other than a holy man have saved Calcutta?

Humility

To anyone who has been to India, I need cite only one instance of Gandhi’s self-imposed humility: his willingness to travel third-class on trains all his life. In a few rare persons, humility describes a natural outflowing of a deferring, submissive personality. To others it is a learned trait imposed upon every impulse to act arrogant and assertive. Gandhi would, I think, put himself in the latter category. He had no innate desire to be stepped on, and had shown his assertive qualities splendidly in his battles for personal rights in South Africa. But gradually, as he immersed himself in the scriptures of Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, and Christianity, he became convinced that the humility of a servant was the one posture required by God. Only then did he dispossess himself of material things, strip off his European clothes, and seek out companionship with the poor and suffering.

Later in life, Gandhi’s humility was so integral that he allowed no important personage, not even the royalty, to interfere with it. When Lord Mountbatten offered to fly him to a critical meeting on his private plane, Gandhi chose instead his third-class railway compartment. He caused something of a scandal on a famous visit to England to meet with the leaders of Parliament and with King George. He arrived amid great fanfare and press coverage, and the nation gasped as he tottered down the steamship gangplank wearing only a cotton loincloth and leading a goat (his source of milk) by a rope. Declining offers from the best hotels, he chose instead to stay in an East End slum. He would not even change his uniform or diet for meetings in the palace. Some reporters were scandalized that he would dare meet with a king in a “half-naked” state: Gandhi quietly pondered their objections and replied with a smile, “The king was wearing enough clothes for both of us.”

In India, as the issues of independence and partition began reaching the critical mass just before explosion, Gandhi took off on his celebrated barefoot pilgrimage through the riot-torn Noakhali district. Some congress leaders questioned his decision to waste his time in jerkwater villages at a time when the party was negotiating the future of the subcontinent. “A leader,” said Gandhi, “is only a reflection of the people he leads.” If the small villages do not live together in peace, how will the entire nation?

Gandhi never insisted that political leaders follow his path of rigid discipline; his was a moral and religious crusade and not just a political one. But he did ask that all government ministers live in a simple home with no servants and no car, practice one hour of manual labor daily, and clean his or her own toilet box. Congress leaders wore the homespun cotton uniform he espoused, and often conducted important meetings while spinning cotton threads. But despite this cosmetic gesture, the congress soon opened up to wealth, corruption, and venality—nothing pained Gandhi more the last few years of his life.

Gandhi’s adopted style of humility permeates his autobiography. In it, he treats rivals who cause him intense pain and strife with respect and courtesy. Look at your own errors with a convex lens, said Gandhi, and at others’ with the reverse.

A convex lens applied to American culture would not reveal a surfeit of humility. Cultural observers have often noted our national characteristic of narcissism. Tom Wolfe described the seventies as the “me decade” and historian Christopher Lasch diagnosed our “culture of narcissism.” Two recent comprehensive studies—Daniel Yankelovich’s New Rules and Amitai Etzioni’s An Immodest Agenda—have confirmed that the pervasive spirit of self-fulfillment and narcissism challenges the structure of our society.

Unfortunately, the gospel message that gets widest exposure in America today follows the cultural mainstream. It offers the appeal “God has something good in store for you” and a pilgrimage toward self-discovery. Jesus’ frequent statements about finding oneself by losing oneself and carrying a cross are left unexegeted. In America a success-based theology as often as not works out plausibly well, if only because the resources of this nation are so large. But such a theology has little to say to Christians in Poland or Albania or Nepal or Iran; there, faith in Christ guarantees compounded suffering.

In his own study of the New Testament, Gandhi found an appeal to seek truth with the whole heart, expecting nothing, regardless of results. He used to sing an Indian poem as he walked between the rice paddies of Noakhali as his own people were persecuting him, “If they answer not your call, walk alone, walk alone.” In America that message, frankly, does not sell. The fact that Western Christianity exclusively stresses the success side of faith may, however, explain why Asia of all continents has proven least receptive to the gospel.

Nonviolence

History will remember Gandhi for the principles of nonviolence and civil disobedience that he extended for the first time to a national scale. He would likely have rejected both these negative terms—why define a movement by something it is not, nonviolent and disobedient?—and chosen a positive term such as Truth Force. The principles evolved in his thinking, expanding outward from his personal response to beatings and discrimination and culminating in a universal principle with no exceptions.

South Africa had given Gandhi ample opportunity to prove his personal courage. He was tossed off trains, ejected from hotels and restaurants, charged by mounted police, and jailed for almost a year. He learned to face danger with no force but courage. In those early days, he did not apply nonviolence nationally. He supported Britain in the Boer War and in World War I, organizing an Indian ambulance corps in each conflict to help the British cause. Indians were not yet ready for nonviolence, he claimed.

In India he turned to nonviolent means as much out of pragmatism as out of religious conviction. “Great Britain,” he warned, “wants us to put the struggle on the plane of machine guns where they have the weapons and we do not. Our only assurance of beating them is by putting the struggle on a plane where we have the weapons and they have not.” If his supporters ever turned violent during one of his campaigns, Gandhi would call it off. No cause, no matter how just, was worth bloodshed.

Gradually, a deeply felt religious doctrine formed in his mind, which gave sacred sanction to the principles he already lived by. Violence against another human being contradicted everything he believed about universal human dignity, even if the particular human might be a British officer firing into an unarmed crowd. You cannot change a man’s conviction through violence, he believed. Violence only brutalizes and separates, it does not reconcile. Gandhi records that he reached a turning point in his life when he came across Jesus’ admonition that his followers should turn the other cheek to their persecutors. That statement provided the moral plinth for a doctrine he had already accepted personally.

In later years, Gandhi became absolutely inflexible on this issue. During World War II he counseled first the Ethiopians invaded by Nazi armies, then the Jews, then Great Britain to invite their enemies in and stand before the slaughter with serenity and a clear conscience. When the atom bomb was revealed, Gandhi told his followers if one were dropped on India they should stand, “looking up, watching without fear, praying for the pilot.”

“I would die for the cause,” he concluded, “but there is no cause I’m prepared to kill for.” Since Gandhi, other political leaders have adopted his tactics. Martin Luther King, Jr., who considered himself a spiritual successor, brought those concepts to America and fought violence with nonviolence. Historically, the results have been mixed. Relatively free societies have proved open to change based on moral force. In closed societies such as Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Russia, as well as in Chile, South Korea, and the Philippines, nonviolent dissent and civil disobedience have done little but strengthen the grip of the oppressors.

Of all Gandhi’s guiding principles, this one has lodged firmly in Western consciousness, and today the doctrine of nonviolence is being hotly debated by American Christians. Groups as diverse as Catholic bishops and a Fuller seminary gathering of evangelicals are reconsidering war in light of the preponderance of nuclear arms. Articles on nonviolence and pacifism appear in major Christian periodicals, many with a strident tone that does little justice to the complexity of the issues involved. (Ironically, some Hindu leaders, Gandhi’s own religious heirs, are suggesting that this principle grew out of his Christian influences and has no place in Hinduism.)

Civil disobedience also has gained respectability as a force for change in democracies. Francis Schaeffer, in A Christian Manifesto, gave his blessing to selected calls for civil disobedience. Still, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s example stands as the most direct application of Gandhian principles in modern Western society. Legally, at least, he broke the back of discrimination in this country by mimicking Gandhi’s tactics. The climax came on the bridge to Selma when King’s unarmed followers met policemen armed with fire hoses, clubs, and snarling German shepherds. Nonviolent force met violent force. When King instructed his followers to kneel down and the television cameras ground away, in a few minutes the civil-rights struggle was all but over. King knew, as did Gandhi, that legal victories come easily; social change takes much longer.

Village Self-Sufficiency

Gandhi held this principle dear above all others, and yet his teaching on the subject has been rejected by India as well as by the West that had already gone too far to listen. Gandhi truly believed the only hope for the East lay in forming economically self-sufficient village units. He had seen the colonialist exploitation methods of taking raw materials overseas, manufacturing them, and shipping the finished product back to India at high profit.

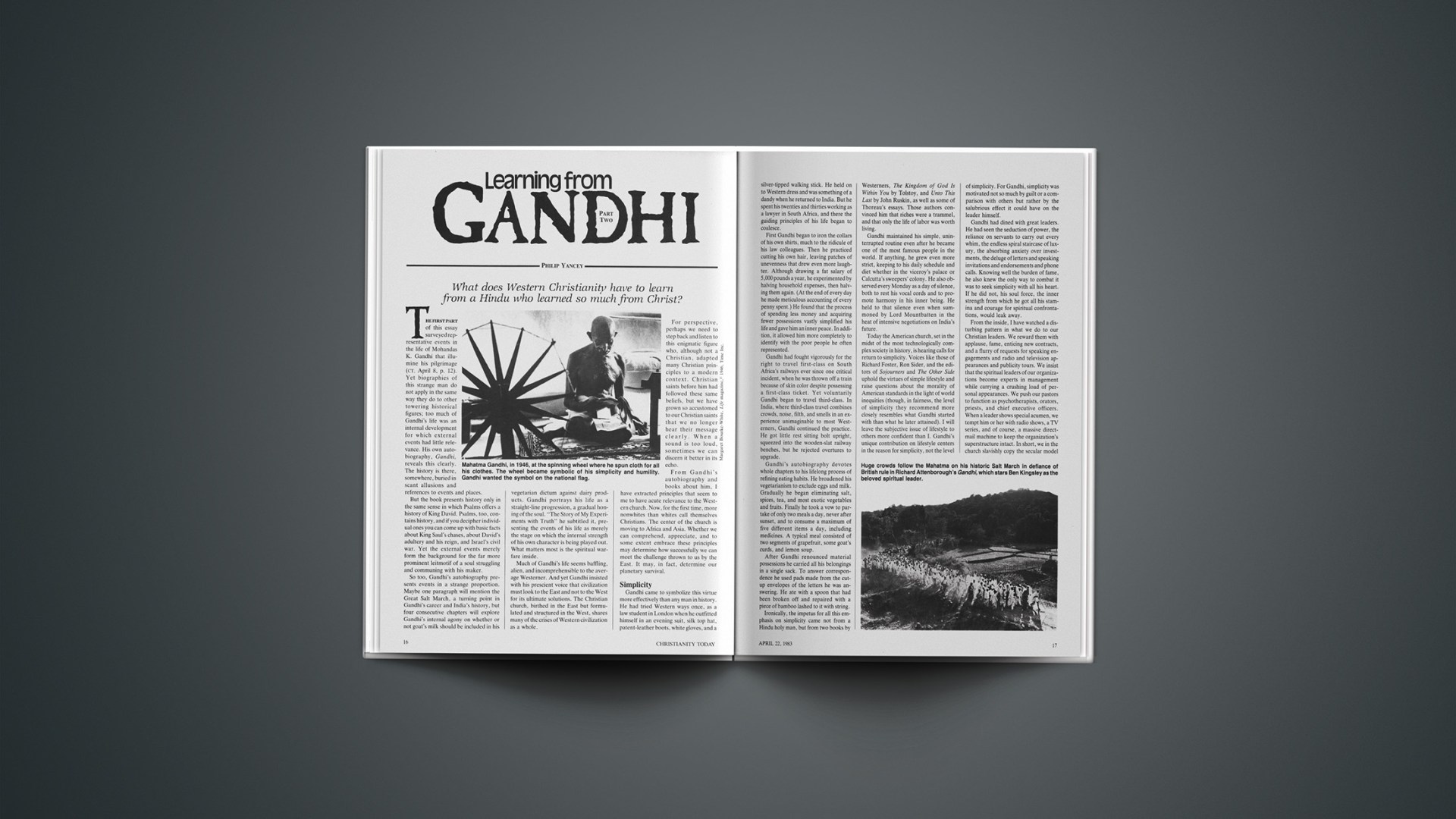

Gandhi advocated closing down textile mills and replacing them with wooden spinning wheels. When the time came for India to choose a new flag, he strongly lobbied for the spinning wheel as the national symbol to print on the flag. Presaging a shift to come, congress leaders adopted a more conventionally nationalistic symbol, ancient Emperor Ashok’s pole with a three-headed lion. Gandhi’s beliefs stemmed not from a quixotic back-to-the-land idealism but rather a practical response to what he observed in India’s cities. Urbanization was sucking people out of the villages, destroying centuries-old family patterns, breeding crime and violence, and choking the skies of India with pollution. Only in a small village context could his goals of human dignity and simplicity find truly fertile ground.

Gandhi also had doubts about modern technology. He believed people who had cars, radios, and well-stocked refrigerators and clothes closets would become psychologically insecure and morally corrupt. He knew enough about soil conservation to realize that India’s land, farmed without interruption for 5,000 years, could not tolerate even a few decades of the kind of soil abuse brought about by high-technology farming. He had questions about how long energy sources would hold up. And besides, Gandhi said, he would continue to recommend cows until a tractor was invented that could produce milk, yogurt, and dung.

On this issue, Gandhi’s words reverberate prophetically. Too late we in the West are realizing the cost of pell-mell industrialization. Dependence on energy has changed the entire world economic order. We may find ways to reclaim the lakes killed by acid rain, and may be able to restock forests and wildlife, but certain things will never be regained. In 150 years, Iowa has lost more of its topsoil than India lost in 5,000 years using more primitive methods.

Perhaps the most insidious result of our consumer society has been its effect on the plausibility of alternative lifestyles. A society whose economic fabric depends on constant growth requires that its citizens have ever-expanding needs and wants. If 10 million Christians, with the highest of motives, decided to cut out all extravagance and live more simply by trading in their cars, wearing unfashionable clothes, raising their own food, and eliminating appliances, economic chaos would result. By their actions those Christians would immediately put tens of thousands of people out of work. That dilemma is exactly what Gandhi wanted to avoid in India.

In the West, it will take one with soul force equal to Gandhi’s to change the prevailing dogma. Some prophets, such as Jacques Ellul, cry out. We may be forced to change our profligate ways some day, when the soil is depleted, the aquifers drained, and all the oil wells pumped dry. But those crises will wait another 50 years at least; those yet unborn will worry about them.

Vicarious Suffering

Very early in his career, while Gandhi was organizing a commune, or ashram, in South Africa, two of the young people under his tutelage lapsed into some act he would only call “a moral fall.” Grieving deeply, Gandhi agonized for days over an appropriate response. Most members of the ashram were calling for strict punishment of the offenders. But it seemed to Gandhi a guardian or teacher was at least partly responsible for the failures of his ward or pupil. He doubted whether the other students would realize the depth of his distress and the seriousness of sin unless he did some penance. And so, in response to the students’ transgression, he went on a total fast for seven days and took only one small meal a day for four and one-half months. “My penance pained everybody,” he concluded, “but it cleared the atmosphere. Everyone came to realize what a terrible thing it was to be sinful, and the bond that bound me to the boys and girls became stronger and truer.”

Over the next decades, Gandhi expanded his reach to embrace the suffering of all India. He rode in cramped train compartments and lived with Untouchables. Barefoot, he carried his “ointment” of healing all across his wounded land. In a supreme irony, his most powerful weapon turned out to be the most primitive of all denials, the refusal to take food, in a nation famous for its starvation and malnutrition. He fasted to oppose repressive taxes, and to oppose the violence done to demonstrators. He fasted when his fellow politicians were acting divisively. Gandhi sought out and absorbed the sufferings of his people, and in the process a bond of love joined them to him as to no other leader.

I have already recounted the near-miraculous effects of Gandhi’s penultimate fast in Calcutta. Out of fear that indirectly they might be responsible for the death of the Great Soul, millions of Hindus and Moslems steadfastly resisted the violence that was erupting in other parts of India. After Calcutta, the last year of his life, Gandhi announced one last fast. This one occurred in New Delhi, the capital of the brand-new country, a capital that in early 1948 lay under a pall of smoke.

Five million refugees had staggered across the Punjab from Pakistan toward the capital, and many of them were now living in the squalor of Delhi’s refugee camps. They had been preyed upon, raped, and brutalized by hordes of Moslems, and these Hindus wanted revenge. They looted Moslem homes, mosques, and shops and punished their owners. As a government, India was refusing to pay 55 million pounds it owed Pakistan, fearing that the money might be used for arms against their own nation. Delhi was in no mood for mercy or compromise.

When Gandhi arrived and sensed the hatred for himself, he announced a fast unto death. His doctors pled against it; he had not yet recovered from the near-fatal fast in Calcutta. Outside, the crowds had a different reaction. They had had their fill of the shriveled old man and his hallucinations of peace and brotherhood. Gangs of Hindus marched past Gandhi’s house with a new chant on their lips, one he had never before heard: “Let Gandhi die! Let Gandhi die!”

For a few days it seemed that the city of Delhi and the nation of India had gone incurably mad. Somehow, one more time, the Great Soul—contained within a body barely 100 pounds and slipping in and out of comas—cast his spell on the country. That crumpled figure on a straw pallet became a kind of plexus in which all the nerves of India met. The horrible sufferings of the last few months that had afflicted Moslems, Hindus, and Sikhs came to rest in this one man who refused to eat.

On the fourth day, in desperation, the most powerful leaders in India—Nazis, Communists, and all movements in between—filed by Gandhi’s bed and took a solemn vow to protect Moslems and renounce violence. Truckloads of arms were collected and destroyed. Civic leaders brought him petitions guaranteeing the return of thousands of homes, shops, and mosques to their rightful Moslem owners. The Indian parliament voted to pay their archenemy Pakistan 55 million pounds. At last, after every one of Gandhi’s strict conditions had been met and the country again was at peace, Gandhi agreed to break his fast. It had lasted 121 hours.

Two weeks later, his wasted body again lay on that straw pallet, killed not by a fast but by three bullets from a Hindu fanatic who resented what he saw as Gandhi’s betrayal of his nation. In that last act of death, Gandhi accomplished more than the thousands of policemen and soldiers who were vainly patrolling villages in the Punjab. With Gandhi’s death, all India paused. Communal killing stopped. Singlehandedly, he had shocked the young nation to its senses. A holy man in Bombay walked through the city crying, “The Mahatma is dead. When comes another such as he?”

Many of Gandhi’s accomplishments died with him. His beloved nation took a different path than the one he had advocated. Since his death, the world has grown more violent, more belligerent, more repressive, and less receptive to his core beliefs. But this strange, baffling man had somehow raised men and women above the level of their usual selves. His only claim to leadership was the force of his own soul. He held no office, and any who obeyed him did so voluntarily. Yet had any man in history commanded such allegiance from so many?

Last November I had occasion to spend a month in the land of Gandhi. Toward the end of the trip, I found myself in a Christian community in New Delhi, a kind of ashram composed of young Indians who are trying to work out corporately Jesus’ radical call to discipleship. For some time we discussed parallels between Gandhi and Jesus Christ. In many external ways, the two lives followed similar tracks, and Gandhi had freely admitted his most important principles derived directly from Jesus’ teaching. Yet while Gandhi nearly reshaped the whole country, Christianity had barely made a dent in India—less than 3 percent of the population called themselves Christian. Together, we explored whether perhaps the body of Christ had presented Christianity to India, but not the true Christ.

We talked about the perception of Christianity by the average educated Indian. Those who have been to America come back very impressed with the churches. They tell stories about the television evangelists, and how much money they take in each day. They tell of Christian leaders meeting with the President and Presidents themselves claiming to be Christian. Christian leaders tend to be slick, middle-class, well groomed, not the austere holy men they are accustomed to in India. No one is called “the Great Soul” in the West. Reflecting on Christianity, these Indians tend to revert to hackneyed words like power, money, success. When they describe American Christianity, in fact, what they are describing is American culture. They rarely talk about Jesus’ life or the principles he laid down.

Wanting to encourage my fellow Christians in New Delhi, I reminded them of Gandhi’s statement that the answer to the world’s problems must come from the East and not the West. I urged them to take the best of what their continent had produced, some of the same principles I have reviewed above, and trace the Christian roots. They could challenge our nation in a way that we Americans could not, as shown by the fact that young Americans will sometimes listen to Gandhi before they will listen to Jesus. The world may be ready for this message again, I said.

One thoughtful young Indian who had sat quietly throughout the discussion spoke up at this. “I don’t understand,” he said. “You seem to say that the West in general is receptive to a saint, someone like Gandhi who stands apart from culture. But is the church receptive? You have said that American Christianity has never produced a saint who follows along the lines of a Gandhi. All the Christian leaders are so different from Gandhi. You seem to imply that if a Gandhi rose up in the American church today, he would not be taken seriously, would perhaps be laughed at and rejected. And yet those same Christians say they worship Jesus Christ. Why don’t they reject him? He lived a simple life, preached love and nonviolence, refused to compromise with the powers of his world. He called on his followers to ‘take up a cross’ and bear the sufferings of the world. Why don’t American Christians reject him?”

It was a good question, one I still have not found an answer to.