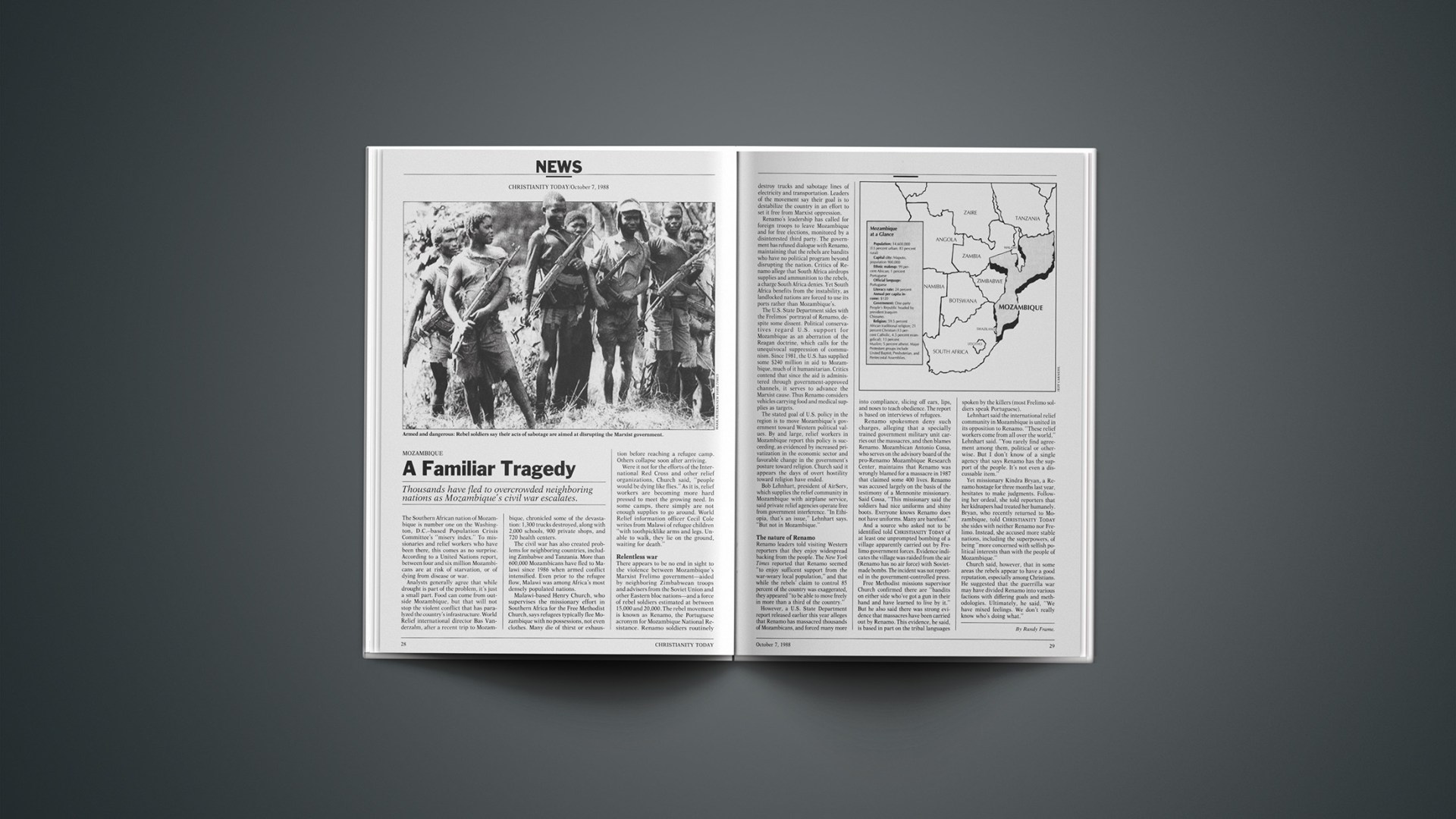

NEWS

MOZAMBIQUE

Thousands have fled to overcrowded neighboring nations as Mozambique s civil war escalates.

The Southern African nation of Mozambique is number one on the Washington, D.C.—based Population Crisis Committee’s “misery index.” To missionaries and relief workers who have been there, this comes as no surprise. According to a United Nations report, between four and six million Mozambicans are at risk of starvation, or of dying from disease or war.

Analysts generally agree that while drought is part of the problem, it’s just a small part. Food can come from outside Mozambique, but that will not stop the violent conflict that has paralyzed the country’s infrastructure. World Relief international director Bas Vanderzalm, after a recent trip to Mozambique, chronicled some of the devastation: 1,300 trucks destroyed, along with 2,000 schools, 900 private shops, and 720 health centers.

The civil war has also created problems for neighboring countries, including Zimbabwe and Tanzania. More than 600,000 Mozambicans have fled to Malawi since 1986 when armed conflict intensified. Even prior to the refugee flow, Malawi was among Africa’s most densely populated nations.

Malawi-based Henry Church, who supervises the missionary effort in Southern Africa for the Free Methodist Church, says refugees typically flee Mozambique with no possessions, not even clothes. Many die of thirst or exhaustion before reaching a refugee camp. Others collapse soon after arriving.

Were it not for the efforts of the International Red Cross and other relief organizations, Church said, “people would be dying like flies.” As it is, relief workers are becoming more hard pressed to meet the growing need. In some camps, there simply are not enough supplies to go around. World Relief information officer Cecil Cole writes from Malawi of refugee children “with toothpicklike arms and legs. Unable to walk, they lie on the ground, waiting for death.”

Relentless War

There appears to be no end in sight to the violence between Mozambique’s Marxist Frelimo government—aided by neighboring Zimbabwean troops and advisers from the Soviet Union and other Eastern bloc nations—and a force of rebel soldiers estimated at between 15,000 and 20,000. The rebel movement is known as Renamo, the Portuguese acronym for Mozambique National Resistance. Renamo soldiers routinely destroy trucks and sabotage lines of electricity and transportation. Leaders of the movement say their goal is to destabilize the country in an effort to set it free from Marxist oppression.

Renamo’s leadership has called for foreign troops to leave Mozambique and for free elections, monitored by a disinterested third party. The government has refused dialogue with Renamo, maintaining that the rebels are bandits who have no political program beyond disrupting the nation. Critics of Renamo allege that South Africa airdrops supplies and ammunition to the rebels, a charge South Africa denies. Yet South Africa benefits from the instability, as landlocked nations are forced to use its ports rather than Mozambique’s.

The U.S. State Department sides with the Frelimos’ portrayal of Renamo, despite some dissent. Political conservatives regard U.S. support for Mozambique as an aberration of the Reagan doctrine, which calls for the unequivocal suppression of communism. Since 1981, the U.S. has supplied some $240 million in aid to Mozambique, much of it humanitarian. Critics contend that since the aid is administered through government-approved channels, it serves to advance the Marxist cause. Thus Renamo considers vehicles carrying food and medical supplies as targets.

The stated goal of U.S. policy in the region is to move Mozambique’s government toward Western political values. By and large, relief workers in Mozambique report this policy is succeeding, as evidenced by increased privatization in the economic sector and favorable change in the government’s posture toward religion. Church said it appears the days of overt hostility toward religion have ended.

Bob Lehnhart, president of AirServ, which supplies the relief community in Mozambique with airplane service, said private relief agencies operate free from government interference. “In Ethiopia, that’s an issue,” Lehnhart says. “But not in Mozambique.”

The Nature Of Renamo

Renamo leaders told visiting Western reporters that they enjoy widespread backing from the people. The New York Times reported that Renamo seemed “to enjoy sufficent support from the war-weary local population,” and that while the rebels’ claim to control 85 percent of the country was exaggerated, they appeared “to be able to move freely in more than a third of the country.”

However, a U.S. State Department report released earlier this year alleges that Renamo has massacred thousands of Mozambicans, and forced many more

into compliance, slicing off ears, lips, and noses to teach obedience. The report is based on interviews of refugees.

Renamo spokesmen deny such charges, alleging that a specially trained government military unit carries out the massacres, and then blames Renamo. Mozambican Antonio Cossa, who serves on the advisory board of the pro-Renamo Mozambique Research Center, maintains that Renamo was wrongly blamed for a massacre in 1987 that claimed some 400 lives. Renamo was accused largely on the basis of the testimony of a Mennonite missionary. Said Cossa, “This missionary said the soldiers had nice uniforms and shiny boots. Everyone knows Renamo does not have uniforms. Many are barefoot.”

And a source who asked not to be identified told CHRISTIANITY TODAY of at least one unprompted bombing of a village apparently carried out by Frelimo government forces. Evidence indicates the village was raided from the air (Renamo has no air force) with Soviet-made bombs. The incident was not reported in the government-controlled press.

Free Methodist missions supervisor Church confirmed there are “bandits on either side who’ve got a gun in their hand and have learned to live by it.” But he also said there was strong evidence that massacres have been carried out by Renamo. This evidence, he said, is based in part on the tribal languages spoken by the killers (most Frelimo soldiers speak Portuguese).

Lehnhart said the international relief community in Mozambique is united in its opposition to Renamo. “These relief workers come from all over the world,” Lehnhart said. “You rarely find agreement among them, political or otherwise. But I don’t know of a single agency that says Renamo has the support of the people. It’s not even a discussable item.”

Yet missionary Kindra Bryan, a Renamo hostage for three months last year, hesitates to make judgments. Following her ordeal, she told reporters that her kidnapers had treated her humanely. Bryan, who recently returned to Mozambique, told CHRISTIANITY TODAY she sides with neither Renamo nor Frelimo. Instead, she accused more stable nations, including the superpowers, of being “more concerned with selfish political interests than with the people of Mozambique.”

Church said, however, that in some areas the rebels appear to have a good reputation, especially among Christians. He suggested that the guerrilla war may have divided Renamo into various factions with differing goals and methodologies. Ultimately, he said, “We have mixed feelings. We don’t really know who’s doing what.”

By Randy Frame.