In Shoah, Claude Lanzmann's documentary on the Holocaust, a leader of the Warsaw ghetto uprising talked about the bitterness that remains in his soul over how he and his neighbors were treated by the Nazis: "If you could lick my heart," he says, "it would poison you."

Researchers are finding that this Holocaust survivor's sentiment is not necessarily metaphorical. While the biblical practice of forgiveness is usually preached as a Christian obligation, social scientists are discovering that forgiveness may help lead to victims' emotional and even physical healing and wholeness.

Academic interest in person-to-person forgiveness is relatively new. As recently as the early 1980s, Dr. Glen Mack Harnden went to the University of Kansas library and looked up the word forgiveness in Psychological Abstracts. He couldn't find a single reference.

This earlier neglect is being remedied at a startling pace. Former President Jimmy Carter, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and former missionary Elisabeth Elliot are leading a $10 million "Campaign for Forgiveness Research," established as a nonprofit corporation to attract donations that will support forgiveness research proposals.

In May of 1998, the John Templeton Foundation awarded research grants for the study of forgiveness to 29 scholars. Some of the projects now being funded include Forgiveness After Organizational Downsizing; Forgiveness in Family Relationships; Secular and Spiritual Forgiveness Interventions for Recovering Alcoholics; The Effects of Forgiveness on the Physical and Psychological Development of Severely Traumatized Females; Forgiveness, Health, and Wellbeing in the Lives of Post-Collegiate Young Adults; Challenges to Forgiveness in Marriage; and Healing, Forgiveness, and Reconciliation in Rwanda.

Through these and other studies, researchers are trying to determine the ways in which the spiritual act of forgiveness can promote personal, interrelational, and social well-being. Harnden is enthusiastic about the personal benefits of forgiveness. "It not only heightens the potential for reconciliation," he says, "but also releases the offender from prolonged anger, rage, and stress that have been linked to physiological problems, such as cardiovascular diseases, high blood pressure, hypertension, cancer, and other psychosomatic illness."

Numerous other studies are in progress, many of them headquartered at the unlikely address of the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UWM).

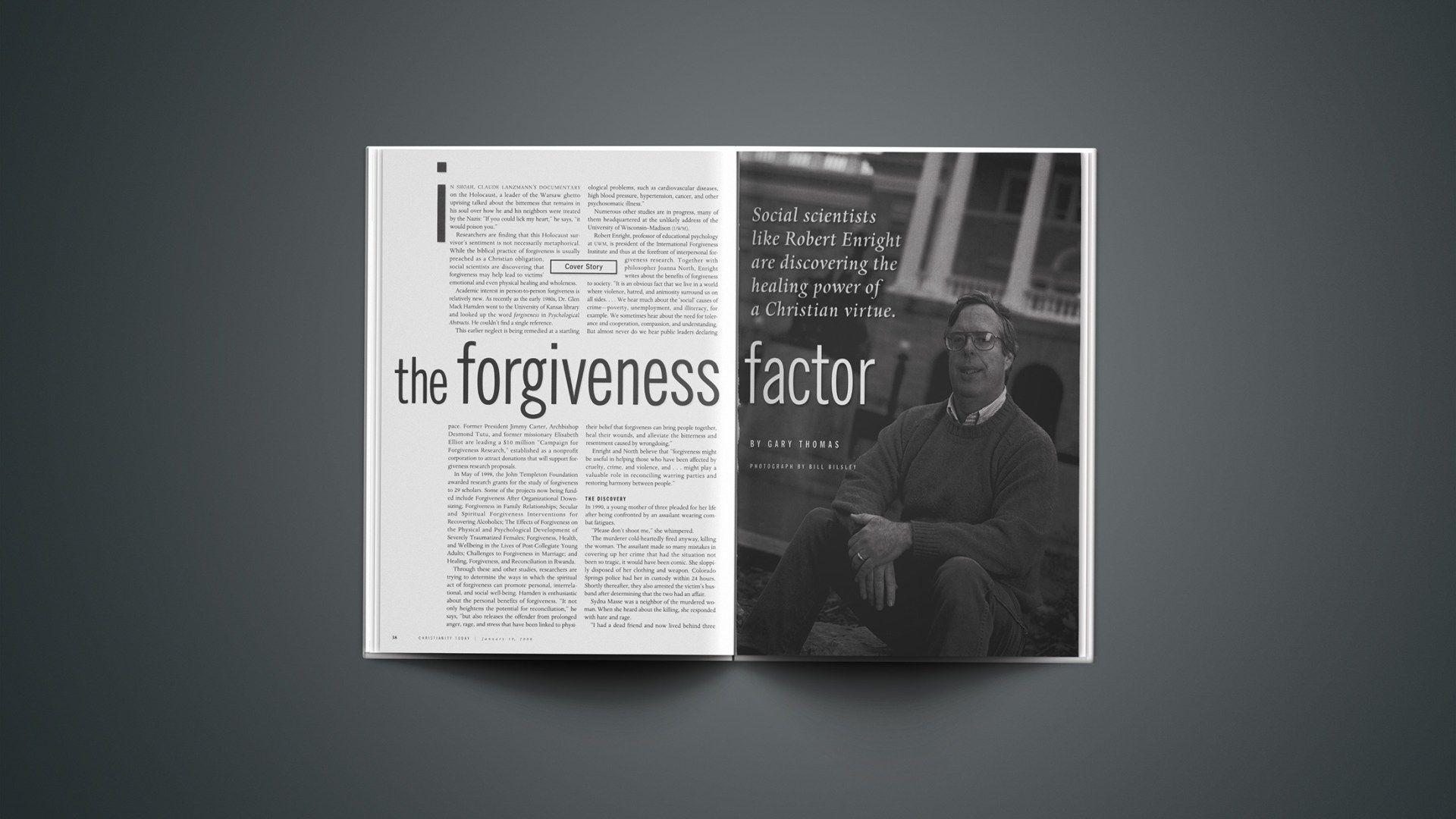

Robert Enright, professor of educational psychology at UWM, is president of the International Forgiveness Institute and thus at the forefront of interpersonal forgiveness research. Together with philosopher Joanna North, Enright writes about the benefits of forgiveness to society. "It is an obvious fact that we live in a world where violence, hatred, and animosity surround us on all sides. … We hear much about the 'social' causes of crime—poverty, unemployment, and illiteracy, for example. We sometimes hear about the need for tolerance and cooperation, compassion, and understanding. But almost never do we hear public leaders declaring their belief that forgiveness can bring people together, heal their wounds, and alleviate the bitterness and resentment caused by wrongdoing."

Enright and North believe that "forgiveness might be useful in helping those who have been affected by cruelty, crime, and violence, and. … might play a valuable role in reconciling warring parties and restoring harmony between people."

THE DISCOVERY

In 1990, a young mother of three pleaded for her life after being confronted by an assailant wearing combat fatigues.

"Please don't shoot me," she whimpered.

The murderer cold-heartedly fired anyway, killing the woman. The assailant made so many mistakes in covering up her crime that had the situation not been so tragic, it would have been comic. She sloppily disposed of her clothing and weapon. Colorado Springs police had her in custody within 24 hours. Shortly thereafter, they also arrested the victim's husband after determining that the two had an affair.

Sydna Masse was a neighbor of the murdered woman. When she heard about the killing, she responded with hate and rage.

"I had a dead friend and now lived behind three motherless kids. I felt I had every right to hate the murderer who caused this."

Sydna grew "physically hot" when the murderer's name—Jennifer—was even mentioned or her picture was flashed on television. "For a while, I couldn't even read the newspaper articles," she admits.

Sydna's hate wasn't a solitary affair. "The whole city and state hated her," she says. Jennifer's life sentence did little to ameliorate Sydna's passion. "There was no relief in her sentencing. That's the thing with hatred and bitterness—it eats you alive. Every time I passed the house, I missed Diane and became angry all over again."

Shortly after Jennifer received her sentence, Sydna began going through a Bible study that included a chapter on forgiveness. Sydna prayerfully asked God whom she needed to forgive, and in her words, "Jennifer's name came right to my head. I literally did a whiplash and protested, 'No way I can forgive her. She killed my friend! She killed a mother of three!'"

In spite of her reluctance, Sydna finally acquiesced and wrote a carefully worded letter to Jennifer, expressing her forgiveness. She was caught by surprise by what happened inside her. As soon as Sydna dropped the letter into the mail, "a weight lifted. I felt like I was losing 20 pounds. That's when I learned that anger, bitterness, and unforgiveness keeps you from experiencing the depths of joy."

Enright was shocked at the complete absence of any empirical studies examining forgiveness.

Sydna's experience is right in line with what researchers are finding for a wide range of demographics. In a 1997 study at UWM, Enright and Catherine Coyle sought to determine whether men who identified themselves as hurt by an abortion could benefit from a "structured psychological intervention designed to facilitate forgiveness."

The psychological processes involve 20 delineated steps, including confronting anger, a willingness to consider forgiveness as an option, acceptance of the pain, and the participant realizing that he has needed others' forgiveness in the past. After leading their subjects through this process, researchers found significant decreases in clients' anxiety, anger, and grief.

Radhi Al-Mabuk, Enright, and Paul Cardis published a study in 1995 (Journal of Moral Education, Vol. 24, No. 4) examining forgiveness education with college students who judged themselves to be deprived of parental love. The college students who underwent the more rigorous program had "improved psychological health," including improved self-esteem, hope, and lowered trait anxiety.

In a study among elderly females, John Hebl and Enright found a significant decrease in depression and anxiety among those who participated in their forgiveness program (although the control group experienced some of the same benefits). Furthermore, the re searchers found that the elderly women who participated in their study not only used forgiveness skills to reconcile with a single person, but "also to consider more deliberately forgiveness as a social problem-solving strategy."

AN UNLIKELY RESEARCH TOPIC

Bob Enright is the undisputed father of forgiveness research. He grew up Roman Catholic, fell away from the faith, entered it once again through Methodism, took a journey through evangelicalism, and now is back in Catholicism. He describes himself as an "evangelical Catholic, if there is such a thing."

In 1985, Enright was a tenured full professor, "sitting at the top of the [academic] heap," he says, but getting bored with the mainstream of research on which he focused.

"The field of moral development was not going anywhere at all," he says. At that time he was bringing in the customary one or two grants a year, but finding nothing exciting enough to keep him sufficiently engaged.

"I was enduring a tremendous dissatisfaction with the way I thought my field was going. We were not reaching out to everyday people the way I hoped we would. I wanted to find something in the area of morals that could be of tremendous benefit to others. I took it so seriously that after a sabbatical in 1984, I dumped all my research over a cliff, so to speak, and boy am I glad I did."

As Enright wrestled with how moral research could actually benefit others, his Christian background ignited a small fire. "I kept asking myself, 'If the social sciences are supposed to be part of the helping profession, and if the wisdom of the ages—the Hebrew-Christian Bible—is replete with wonderful stories about the success of person-to-person forgiveness, why haven't the social sciences ever thought to study forgiveness as a primary investigation?'"

It was his academic "aha!" moment.

When Enright looked into the research literature, he was shocked at the complete absence of any empirical studies examining such a practice.

"I was very naïve," he remembers. "I thought there would be something, but there literally was not one study published on the topic [of person-to-person forgiveness] in the social sciences. I would occasionally see the word, but no study focused on it."

As soon as Enright embarked on his new endeavor, he was struck by how his work was received. "Everyday people" were intrigued and delighted when he raised the topic. But the academic world was entirely a different matter.

"Academic eyes would glaze over 90 percent of the time. Nine percent had hate-filled eyes. One percent was delighted."

Funding is the gatekeeper of research, so Enright began applying for grants. His first idea was to help prisoners learn how to forgive others who had wronged them, with the long-term view that by doing this, prisoners might experience empathy for their victims. It was sort of a back-door approach to help prisoners understand how their actions can plague others.

The response couldn't have been less encouraging.

"During one interview, I had a wonderful, hour-long talk with a man who held an editorship from a major psychology journal. Afterward, he confided to me, 'This is so creative and important, I'm going to rate this number one.'"

Three months later, however, the rejection letter arrived. Enright called the editor, who was "rather embarrassed and very hesitant."

When pressed, the editor admitted, "Bob, once I got into the group meeting, they completely and thoroughly trashed your idea."

"What did they say?" Enright asked.

"People were angry. 'You should never give money to prisoners to have them forgive,' they said. 'If anything, they should ask forgiveness of us.'"

Enright was discouraged. "I thought, that's been the problem. We've never tried it the other way. I wanted to prime the pump by having prisoners learn to forgive first and then maybe they'd ask for forgiveness themselves."

The next year, Enright applied for the same grant with essentially the same project. This time, the interview with the preeminent psychologist took all of ten minutes.

"Bob," he warned, "you do know you're going to have trouble for the rest of your career with this study of forgiveness, don't you?"

For nearly a decade, Enright endured the academic equivalent of "shunning." He didn't receive a single dollar of grant money, which is academia's way of saying, "Whatever this man is doing isn't very important."

"It was very embarrassing," Enright admits.

It is even more surprising that Enright persisted, considering that the school where he teaches isn't exactly welcoming of the Christian tradition. "There isn't a single course on Christianity, per se, at the university," Enright says. "You can major in various religious beliefs, but as far as I know, you can't take a course on Christianity."

"How could you study a topic like forgiveness at the UWM, of all places?" a fellow believer said on learning what Enright was doing. "You're either stubborn as a mule or you're Holy Spirit-inspired."

"I think it's probably both," Enright laughs today. "Without tenacity, you couldn't do this sort of thing."

|

What Forgiveness is not

Adapted from Robert D. Enright, in Niki Denison, "To Live & Forget," On Wisconsin (November-December 1992). |

After Enright worked for a decade, receiving little attention and no money, the Chicago Tribune catapulted his work into the public's awareness. A reporter wrote an article on Enright and the International Forgiveness Institute (which at that time was more an idea than a reality), placing the story in the lifestyle section. The article elicited over 300 calls.

"My wife [Nancy] wanted to put the phone out in the woods," Enright quips. "We realized we were on to something, and [the calls] forced our hand to get the institute going."

Enright started publishing a newsletter, set up a Web site, and kept publishing findings in his field. Finally, the funding caught up to the public's interest, and forgiveness research is now a relatively lucrative endeavor.

"God has a sense of humor," Enright says of the grants freely flowing to his fellow academics.

The Mendota Mental Health Center, a world-renowned mental health institute, recently approached Enright about an intriguing idea to help rehabilitate criminals: Perhaps we could teach them how to forgive first, and then see if that builds empathy for them to seek forgiveness?

Enright responded that he thought the idea was definitely worth exploring.

FAITH AND FORGIVENESS

A book that caught Enright's attention early on was Forgive and Forget by Lewis Smedes. "Prior to Lewis Smedes in 1984," Enright says, "if you collected every theological book about person-to-person forgiveness [as opposed to divine-human forgiveness], you could hold them all in one hand."

Mack Harnden was also motivated by Smedes' seminal work. Fifteen years later, he still can pinpoint the day. "On April 20, 1985, I heard Lewis Smedes speak in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on the topic of forgiveness. That speech directed the future course of my life because I felt that forgiveness is the core, [the] most significant factor in both spiritual and psychological healing."

Smedes, a theologian, set out to write a general book on the theological aspect of forgiveness, but soon discovered that "almost everything that was written about forgiveness was about how God forgives sinful people and how they can experience his forgiveness."

As he reflected on the gospel, it occurred to Smedes that "forgiving fellow human beings for wrongs done to them was close to the quintessence of Christian experience. And, more, that the inability to forgive other people was a cause of added misery to the one who was wronged in the first place."

Wanting to focus on person-to-person forgiveness, Smedes felt he might receive some help from "the literature of psychology," but soon discovered that psychologists were apparently even less interested in the topic than theologians had been.

Social scientists are discovering that forgiveness may help lead to victims' emotional and even physical healing and wholeness.

Smedes says he went into his writing with these questions:

"How does forgiveness work? What goes on in one's mind and spirit when she sets out to forgive someone? What happens after forgiveness? What good comes of it?"

He found that in the past, "human forgiveness had been seen as a religious obligation of love that we owe to the person who has offended us. The discovery that I made was the important benefit that forgiving is to the forgiver. And this is where I think the link between the psychological research and my book is."

This is precisely the thought that has captured the imagination of social scientists. Smedes presents a real-world view of forgiveness. Rather than seeing the aim of forgiveness as exclusively reconciliation, it becomes a matter of self-preservation. "Ideally, forgiving brings reconciliation, but not always," Smedes says. "Reconciliation depends on the response of the person who injured someone and is forgiven. But that person may tell the forgiver to take his forgiveness and shove it down the toilet. Indeed, there is never a real reconciliation unless the wronged person first heals herself by forgiving the person who wronged her.

"Does that render forgiveness invalid? Not at all. The first person who gains from forgiveness is the person who does the forgiving, and the first person injured by refusal to forgive is the one who was wronged in the first place."

The same element of forgiveness that seized the attention of social scientists elicited criticism from some theologians. "Some theologians have said my book is an example of egoistic faith," Smedes admits. "They refer to it as 'therapeutic forgiveness.' Yet the very thing that some theologians have criticized in my approach has been taken up by the healing community as a highly significant and promising mode of healing, perhaps the most important element of all."

Smedes believes that "untold pain is brought about in the world by people's unwillingness to forgive and the corresponding passion to get even. All you have to do is look at Yugoslavia today and you know that that's true."

FORGIVENESS AND GRACE

Though Sydna Masse forgave Jennifer for murdering her friend, she did so initially out of a sense of obligation. "What I didn't expect was what I got in return," she says today.

"I'm sorry for killing your friend," Jennifer wrote in response.

When Sydna read the words, "It hit me like a thunderbolt. I didn't realize I needed to hear that."

But she did.

As a pen-pal relationship grew, Sydna realized that what she once viewed as an obligation—forgiving Jennifer—ended up ministering to both women in some profound ways. She admits that if she hadn't forgiven first, Jennifer never could have confessed to her, as Jennifer didn't even know Sydna existed.

Ironically, Jennifer began ministering to Sydna through her letters. "For some reason, her letters always came on dark days for me. Jennifer became one of my greatest encouragers."

Over time, Sydna began to consider Jennifer a friend "just as much as I had considered Diane a friend."

Sydna undertook forgiveness without the assistance of a psychological model, but the results she experienced are what many researchers are after. Researchers have to overcome certain problems. For instance, how can researchers measure that forgiveness has really taken place, or whatever benefits forgiveness produces?

This is the concern of L. Gregory Jones, dean of the Divinity School and professor of theology at Duke University. While encouraged by the appearance of forgiveness as a topic of research, Jones has some concerns. Some studies are done very well, but others use "a largely disembodied therapeutic model of forgiveness that focuses on isolated individuals—the kind of self-help discussion that may have made forgiveness a fad in contemporary culture but will lack the staying power, conceptually and theologically, for it to last over time," Jones says.

"Forgiveness studies need to focus on people in relationship, both on the need to forgive and on the need to be forgiven," Jones adds. "This is, I think, one of the major features of Christian forgiveness that is lacking in a lot of popular descriptions of forgiveness. They focus only on the need to forgive, where Christian forgiveness emphasizes that we need consistently to understand our need for forgiveness."

In the "more problematic" studies, Jones says, "forgiveness is assumed to have happened simply when someone uses words of forgiveness."

In contrast, "forgiveness is not an all-or-nothing affair. It involves the healing of brokenness, and involves words, emotions, and actions. If persons continue to have feelings of bitterness toward another, there may not be the fullness of forgiveness, but that doesn't mean there is no forgiveness. Rather, the persons are involved in a timeful process."

The better studies recognize forgiveness as a "complex process," Jones says. "There are lots of forgiveness backsliders."

This brings us to the basic and crucial point.

What exactly is forgiveness?

The study by Al-Mabuk, Enright, and Cardis defines forgiveness as "one's merciful response to someone who has unjustly hurt. In forgiving, the person overcomes negative affect (such as resentment), cognition (such as harsh judgments), and behavior (such as revenge-seeking) toward the injurer, and substitutes more positive affect, cognition, and behavior toward him or her."

The three researchers distinguish forgiveness from justice "in that the latter involves reciprocity of some kind, whereas forgiveness is an unconditional gift given to one who does not deserve it."

Many of the researchers use a twofold definition: forgiveness is releasing the other person from retaliation and wishing the other person well.

Smedes prefers a three-part definition. "The first thing one does in forgiving is surrender the right to get even with the person who wronged us," he says. "Secondly, we must reinterpret the person who wronged us in a larger format." This, Smedes says, is to help us avoid creating a "caricature" of the person who wronged us. "In the act of forgiving, we get a new picture of a needy, weak, complicated, fallible human being like ourselves."

The third step is "a gradual desire for the welfare of the person who injured us."

|

The process of forgiveness 1. Don't deny feelings of hurt, anger, or shame. Rather, acknowledge these feelings and commit yourself to doing something about them. 2. Don't just focus on the person who has harmed you, but identify the specific offensive behavior. 3. Make a conscious decision not to seek revenge or nurse a grudge and decide instead to forgive. This conversion of the heart is a critical stage toward forgiveness. 4. Formulate a rationale for forgiving. For example: "By forgiving I can experience inner healing and move on with my life." 5. Think differently about the offender. Try to see things from the offender's perspective. 6. Accept the pain you've experienced without passing it off to others, including the offender. 7. Choose to extend goodwill and mercy toward the other; wish for the well-being of that person. 8. Think about how it feels to be released from a burden or grudge. Be open to emotional relief. Seek meaning in the suffering you experienced. 9. Realize the paradox of forgiveness: as you let go and forgive the offender, you are experiencing release and healing. Adapted from Robert D. Enright, in Scott Heller, "Emerging Field of Forgiveness Studies Explores How We Let Go of Grudges," Chronicle of Higher Education (July 17, 1998). |

Smedes is adamant about separating forgiveness and reconciliation. "Forgiveness happens only in the mind and heart of someone who has been wronged. It is an event in the spirit of the offended person that lays the groundwork for and creates the opportunity for reunion of two people. Forgiveness happens internally in the heart of the forgiver. You can forgive someone and they may never know it."

Jones points out the traditional difference between Christian and Jewish notions of forgiveness. "Jesus tells his disciples that they are authorized and sometimes obligated to forgive in his name. For Jews, only victims can forgive."

Harnden adds that "forgiveness does not preclude the enforcement of healthy and natural consequences on the offender . …Whenever an individual offends another, the offender gives up a certain degree of power in determining his or her own destiny, with the power being given over to the offended."

Smedes would agree. "Some people view forgiveness as a cheap avoidance of justice, a plastering over of wrong, a sentimental make believe. If forgiveness is a whitewashing of wrong, then it is itself wrong. Nothing that whitewashes evil can be good. It can be good only if it is a redemption from the effects of evil, not a make-believing that the evil never happened."

The element of fighting evil has some social scientists looking at forgiveness as a political tool.

ARRESTING THE VIOLENCE

"It's one thing to believe in miracles, it's another to be part of one," says Roy Lloyd, a founding board member of the International Forgiveness Institute and the broadcast news director at the National Council of Churches. Lloyd was part of a 15-member delegation that traveled to Yugoslavia in a successful attempt to get three captured American soldiers released.

Though the media widely portrayed the "rescue mission" as a Jesse Jackson publicity stunt, it was actually led jointly by Jackson and Joan Brown Campbell, then the general secretary of the National Council of Churches. Several years ago, Lloyd and Campbell had some discussions about the role of forgiveness in healing social wrongs in the wake of church burnings.

One young man who had been convicted of setting fire to a church was visited by several pastors during his imprisonment and ultimately made a profession of faith. Upon his release, he returned to the church and publicly asked for forgiveness. The church members surrounded the man and prayed for God to bless him.

The first person who gains from forgiveness is the person who does the forgiving.

Following this experience, both Campbell and Lloyd were eager to apply the principles of forgiveness research to the problems in Yugoslavia. Campbell and Jackson's delegation transcended religious lines—there were mainline Protestants, Jews, Orthodox Christians, and Muslims.

"A number of our basic premises were very important," Lloyd says. "All throughout the trip you heard people from our delegation saying that the cycle of violence needs to be broken and that past injuries shouldn't dictate the present or the future. Forgiveness is first of all a gift that you give to yourself. You shouldn't allow something that happened to you or your ancestors long ago to continue injuring you. The most important thing is wishing the best for yourself as well as for others. In that process, you and those with whom you interact are freed from what has been and can envision what might be."

Lloyd heard both Campbell and Jackson voice these sentiments on several different occasions, but he became slightly disillusioned by media that he describes as "narrow-minded and lazy." On one occasion, Jackson urged reporters to pay careful attention to a rabbi within the delegation, but as soon as Jackson stepped away from the microphone, "the television lights went off. They had their sound bite and didn't want anything more, even though they were missing a major part of the story."

That story, according to Lloyd, is the role forgiveness played in helping to address the problems in Kosovo. "In meetings with the foreign secretary of Yugoslavia and other political leaders, we made points about how the violence needs to stop in Kosovo. We applied the principles of forgiveness research—that people are responsible, but that we shouldn't look at others as enemies, but rather as friends if we want to break the cycle of violence. Forgiveness of deeds long past needs to take place rather than repeating them. We need to envision the best for ourselves and for others, and in that everyone will find a peaceful future."

When members of the delegation met with Slobodan Milosevic, they were well aware that negotiations weren't really possible. "We had nothing to offer," Lloyd admits, "other than a religious, spiritual, and humanitarian approach."

Without political leverage, the leaders spoke of the importance of forgiveness and doing the right thing. "Our delegation told Milosevic that he was treated so poorly in the press because of what he had done. If he wanted to change the press, he had to change his ways."

According to Lloyd, all nine of Milosevic's top advisers (several of whom had met with the Campbell-Jackson delegation) spoke with one voice: "let the soldiers go."

Milosevic ultimately agreed with his advisers, but then it was his turn to practice forgiveness.

"On the very day that [Milosevic promised the soldiers' return], a busload of ethnic Albanians was hit by a bomb while crossing a bridge, killing dozens," Lloyd remembers. "And then [NATO] bombed the ambulance that was going out to help them."

In spite of these events, Milosevic stayed true to his word.

Lloyd says that the soldiers practiced their own brand of forgiveness. "Each of the three young soldiers were very religious, and one of them, Christopher Stone, wouldn't leave until he was allowed to go back to the soldier who served as his guard and pray for him."

In spite of the political ramifications surrounding the delegation, the 15 members called themselves "the Religious Mission to Belgrade." When Jackson finally received the news of the soldiers' impending release, he held off reporters long enough to gather the delegation together for group prayer.

While Lloyd advocates forgiveness, he still believes justice needs to be done in the former Yugoslavia. "Milosevic has done terrible, evil things," he says. "One can forgive him, but one can also call for him to indeed be tried in the Hague for crimes against humanity."

Enright is enthusiastic about Lloyd's work. "I don't know of any other instance where a social scientific research program has been able to use its findings to break into U.S. history, and in such a positive way."

Such stories reinforce Harnden's belief that forgiveness has great potential to solve many social problems, including crime. Retaliation or pursuing vengeance, he says, "often leads to the perpetuation of increasingly a more severe retaliatory, violent response." Harden suggested at an American Psychological Association meeting that forgiveness, not retaliation, "represents the most strategic intervention in reducing violence in our society."

Harnden points out that other methods have surely failed. Between 1960 and 1990, for instance, welfare spending increased by 631 percent, but violent crimes also increased—by 564 percent.

Worldwide trends in violence are no more encouraging. From the 1500s to the 1800s—four centuries—a total of 34.1 million died in war, Harnden says, quoting from research by Donald W. Shriver, former president of Union Theological Seminary in New York. Wars have killed nearly three times that many (107.8 million) during the 1900s alone.

"Forgiveness stops the ongoing cycle of repaying vengeance with vengeance that appears to contribute to the perpetuation of an increasingly violent society," Harnden says.

|

Degrees of Forgiveness The ability to forgive depends on other variables: the nature and severity of the offense, and the nature or type of relationship between the offender and the offended one. When trust is shattered between persons where there is a significant relationship (between spouses, parents and children, or pastors and parishioners), forgiveness can be very difficult to attain. Consequently, one forgiveness researcher (Michelle Nelson) talks about degrees or different types of forgiveness: DETACHED FORGIVENESS There is a reduction in negative feelings toward the offender, but no reconciliation has taken place. LIMITED FORGIVENESS There is a reduction in negative feelings toward the offender, and partial relationship is restored with the offender and a decrease in the emotional investment in the relationship. FULL FORGIVENESS There is a total cessation of negative feelings toward the offender, and the relationship is restored and grows. Adapted from Beverly Flanigan, in Exploring Forgiveness. |

POLITICAL "FORGIVENESS"

Political and social forgiveness made headlines worldwide during the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal. But this, according to Enright, may have muddied the waters more than clarified the issue.

"In many instances where President Clinton was asking for forgiveness, I think he was asking for legal pardon, and those are very different concepts," Enright says. "There was a confusion that then arose by many people that when we forgive we can let go of all the legal ramifications. That's a misunderstanding of forgiveness.

"Forgiveness is one person's heartfelt loving response to another person or people who have hurt the forgiver personally," Enright adds. "Legal pardon is entirely different from that. I can understand people's exasperation and confusion. The vast majority of the U.S. citizenry have no need to forgive President Clinton because most people are not personally offended by what he did; they didn't care about what happened to him and Ms. Lewinsky. When President Clinton asked the nation to forgive him, most were indifferent enough to not have to bother."

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.