The Reverend William Glass is an Anglican priest and theologian, fluent in five languages and possessing an impressive résumé in marketing. His story isn’t one of privilege, however. In Glass’s view, the church saved his life.

Glass grew up desperately poor in a Florida trailer park. His family went to church perhaps once a year, but his religious background was, in his words, “Southern alcoholic.” His father was either absent or abusive, he had no close friends, and when he attended school it was a torment. Barely into his teens, he began to manage the stress with drugs and alcohol.

But then Glass visited a Presbyterian youth group to “impress a girl.” It didn’t change everything overnight: He continued to have a rough life, including a brush with homelessness. But Glass also had friends in churches who took care of him during crises, helped him stay connected, and showed him another way to live.

As Glass sees it, church above all offered him “social and relational capital” that was in short supply in his fragmented communities. “The bonds I formed in church,” he says, “meant that when things got bad, there was something else to do besides the next bad thing.”

Glass’s case might be a dramatic one, but it illustrates a documented pattern in our society: People find their social and personal lives improved—sometimes their lives are even physically saved—when they go to church often.

In 2019, Gallup reported that only 36 percent of Americans view organized religion with “a great deal of confidence,” down from 68 percent in 1975. The study’s authors speculate that this trend has been driven in part by the highly publicized moral failures and crimes of religious institutions and leaders.

The decline in confidence in churches has been accompanied by steep recent declines in both church membership and attendance. Barna Group found that 10 years ago, in 2011, 43 percent of Americans said they went to church every week. By February of 2020, that had dropped 14 percentage points to 29 percent.

But when Americans describe the reasons they seldom or never attend church, scandals don’t get top billing. Instead, people who think of themselves as Christians are more likely to say that they practice their faith in other ways (44 percent) or that there’s something they don’t like about the service (38 percent).

Whether or not outrage is involved, the most common experience of Christians who don’t go to church seems to be less a deliberate choice and more a substitution of habits. Put differently, a large share of Christians are opting to go it alone, moving their faith into quarters so private that even the church is not allowed in.

Obviously this trend drives down church attendance and membership. But less obvious until recently is that it is also harming the well-being of those who have stopped attending. A sizable body of research developed over the past couple of decades suggests that Glass’s story is a powerful instance of a broader reality: Religious participation strongly promotes health and wellness.

This means that Americans’ growing disaffection with organized religion isn’t just bad news for churches; it also represents a public health crisis, one that has been largely ignored but the effects of which are likely to increase in coming years.

Of course, the point of the gospel is not to lower your blood pressure, but to know and love God as you are known and loved by him. We have to distinguish between the imperfect flourishing that is possible in this life and the perfect happiness and joy that is made full in the life to come.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to find large data sets on the life of heaven. But we can study the imperfect variety of happiness, those aspects of health, well-being, and wholeness that pertain to this life and the ways in which religious communities contribute to them. And these are valuable to God, too.

So what are the public health benefits of church attendance? Consider how it appears to affect health care professionals. Some of my (Tyler’s) research examined their behaviors over the course of more than a decade and a half using data from the Nurses’ Health Study, which followed more than 70,000 participants.

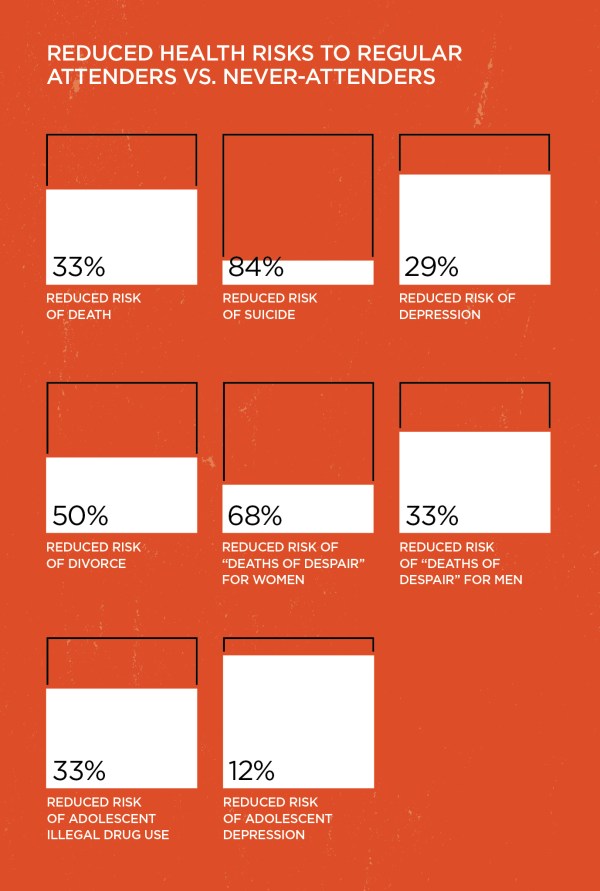

Medical workers who said they attended religious services frequently (given America’s religious composition, these were largely in Christian churches of one stripe or another) were 29 percent less likely to become depressed, about 50 percent less likely to divorce, and five times less likely to commit suicide than those who never attended.

And, in perhaps the most striking finding of all, health care professionals who attended services weekly were 33 percent less likely to die during a 16-year follow-up period than people who never attended. These effects are of a big enough magnitude to make a practical difference and not just a statistical difference.

A religious upbringing also profoundly affects lifelong health and well-being. We found regular service attendance helps shield children from the “big three” dangers of adolescence: depression, substance abuse, and premature sexual activity. People who attended church as children are also more likely to grow up happy, to be forgiving, to have a sense of mission and purpose, and to volunteer.

One of my (Tyler’s) most recent studies of health care professionals indicates that religious service attenders had far fewer “deaths of despair”—deaths by suicide, drug overdose, or alcohol—than people who never attended services, reducing those deaths by 68 percent for women and 33 percent for men in the study.

Our findings aren’t unique. A number of large, well-designed research studies have found that religious service attendance is associated with greater longevity, less depression, less suicide, less smoking, less substance abuse, better cancer and cardiovascular- disease survival, less divorce, greater social support, greater meaning in life, greater life satisfaction, more volunteering, and greater civic engagement.

The findings are extensive and growing. Important recent studies have been led by clinicians and social scientists such as Harold Koenig, Byron Johnson, Ellen Idler, David Williams, Robert Putnam, David Campbell, and W. Bradford Wilcox, along with our team of researchers at the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University.

While some of the early studies on this topic were methodologically weak, the study and research have become stronger and stronger, and many of these findings are now considered well-established. Religious service attendance powerfully enhances health and well-being.

All religions are complex, consisting of doctrinal beliefs, personal devotions, and various kinds of communal observance. Do particular aspects of religious practice affect these health outcomes more strongly than others?

Our research suggests that religious service attendance specifically, rather than private practices or self-assessed religiosity or spirituality, most powerfully predicts health. Religious identity and private spirituality may, of course, still be very important and meaningful within the context of religious life, but their effects on health and well-being don’t seem to be as strong as those of regular gatherings with other believers.

Religious observance seems to decrease depression and increase life satisfaction, particularly by expanding participants’ networks of social support, as well as by promoting optimism or hope and a sense of meaning in life.

Only about a quarter of the effect of service attendance on life expectancy seems to come directly from greater social support; some of the effect appears to depend on the way religious observance decreases depression and smoking and increases optimism, hope, and sense of purpose.

The reason for the fivefold decrease in suicides among service attendees isn’t completely clear, but it may have to do with a mix of protective factors, including churches’ teachings on ending one’s own life, as well as social support found in the community and lower risks of depression and alcohol abuse.

A similar mix of support and teachings discouraging divorce and marital infidelity and encouraging love and mutual service likely also help to explain lower divorce rates among those attending religious services. However, those positive outcomes for marriage probably also depend on the many programs within religious communities that support families and marriages, and the greater levels of life satisfaction and lower depression for the religiously observant within married life.

Another important pathway from religious worship to health and well-being may run through forgiveness. Many religions connect God’s forgiveness of human sins to our forgiveness of one another. Religious Jews seek God’s forgiveness on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), but only after having sought forgiveness of one another on the day prior (Erev Yom Kippur). For Christians, forgiving is a nonnegotiable part of practicing their faith. Many Christians ask God daily to “forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors” (Matt. 6:12) but even without this prayer, the biblical teaching is that Christians must forgive (Matt. 6:15).

Experiments to help people become more forgiving (as well as a literature review that sorted through findings from many studies) indicate that forgiveness is linked to less depression and greater hope. Forgiveness seems to achieve these effects both by promoting greater control over one’s emotions and by offering an alternative to either suppressing one’s anger or endlessly ruminating over it.

In sum, there are a number of ways in which religious service attendance might positively influence a person’s mental and physical well-being, including providing a network of social support, offering clear moral guidance, and creating relationships of accountability to reinforce positive behavior.

If you were trying to map the factors that affect well-being in churchgoers, it would look more like a web than a flowchart. The causal pathways in each of these cases are numerous, overlapping, and likely mutually reinforcing. In churches, each factor that causes well-being is enhanced by the combination with other factors.

Unsurprisingly, each of these causes—social support, moral guidance, and accountability—is flagged as a role of the church in the New Testament.

For instance, in the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus prescribes a system of escalating accountability for his followers, the sort of strategy that can help people live well with each other (18:15–16). Christians as a community are called on to help each other repent, change, and reconcile.

The letter to the Hebrews highlights the importance of church teaching, particularly as it is lived out with others: “And let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day drawing near” (10:24–25, ESV).

This regular diet of encouragement and exhortation might explain some of the effects of religious services attendance on social support, lower divorce, greater meaning and purpose in life, greater life satisfaction, more charitable giving, more volunteering, and greater civic engagement.

Many Christians, however, experience church attendance not as involvement in a particularly engaging Rotary Club but as an encounter with God made flesh. In the Bible as well as in the church, we see God’s power alongside the forces we can study.

The apostle Paul’s metaphor of the church as a body may also help us understand part of the power of communal religious life. In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul writes, “Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ. … The eye cannot say to the hand, ‘I don’t need you!’ And the head cannot say to the feet, ‘I don’t need you!’ … Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it” (12:12, 21, 27).

Through their diverse gifts, and the help they provide one another, members of churches are supported in religious faith and spiritual growth, but also in more mundane matters, from care during illness to help finding work after a layoff.

Paul’s use of the body imagery is not merely a metaphor, however, but a claim about the intensity and reality of Christ’s presence in and through the church. In the Book of Acts, the experiences of the church even seem to count as Christ’s own: When Jesus confronts the still-unbelieving Saul on the Damascus Road about his attacks on the church, he asks, “Why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:4).

The thought of the church as Christ’s body sets a “sacred canopy” (to borrow an expression from sociologist Peter Berger) over every aspect of Christian communal life. In this context, moral injunctions are not just good advice, but echo with the fire and thunder of Sinai, while service to the poor and imprisoned is not simply a good deed, but a ministry Christ accepts as if it were done for him (Matt. 25:37–40). It is small wonder that participation in such a community has transformative effects on many aspects of life.

Needless to say, people don’t generally become religious to add years to their lives. It isn’t actuarial tables that make converts; it’s the witness of the saints, including the ordinary ones; the beauty of a Bach cantata or a Wesley hymn or even a radio hit; and everyday experiences of love, kindness, and forgiveness (not to mention the working of the Holy Spirit).

Nonetheless, it’s clear that religion does have important public health implications.

As William Glass’s story demonstrates, religious communities provide a strong social safety net that other institutions can’t easily replace. This has important implications, not only for religious communities themselves, but also for counseling and health care, for public policy, and for individuals and families.

In the first place, all religious believers should be glad to know that religious service attendance in particular strongly affects health and well-being, and it is only natural that they would want to spread the word.

But it shouldn’t be left only to churchgoers and ministers to promote service attendance. For example, we might wonder whether clinicians owe it to their religious patients to ask about service attendance as they’re asking about other behaviors.

The research results on religion and health do not imply that physicians should universally “prescribe” religious service attendance. Agnostics would be understandably reluctant to recite the Apostles’ Creed even if they thought it would help their depression. Due caution ought also to be taken for those with prior negative experiences, or even experienced abuse, in religious communities, but a few brief spiritual history questions may help guide professionals.

For most Christians whose faith tells them to meet with others, hearing a doctor ask whether they’ve been attending services might encourage them in a way their pastor or family member can’t.

Beyond the personal level, our public policies should also make sure that the institutions that provide such benefits can go on doing so.

Saving the government money isn’t the primary reason institutions can get tax exemptions. Still, it is worth taking into account how much of a health and well-being boost our nation gets from church services whenever we reevaluate churches’ tax-exempt status.

Religious participation is not simply a matter of civil liberties but is also a significant public health concern. As such, it ought to figure more prominently in public-policy discussions of suicide and other worrying social trends, such as the rise of teen depression or the decline in marriage rates.

When we Americans try to solve social problems, all of us—not just Christians—should remember the role religion plays in people’s lives. For example, with concern over rising suicide rates in the United States, many researchers and commentators have focused on important factors such as the overprescription of opioids or declines in manufacturing jobs.

Our own research indicates that declining religious service attendance accounts for about 40 percent of the rise in suicide rates over the past 15 years. If the declines in attendance could have been prevented, how many lives could have been saved?

The public health benefits of religious participation underscore the importance of promoting and protecting religious institutions and religious freedom. They also suggest the need for significant changes in how the contributions of religious institutions are portrayed in the media, the academy, and beyond.

Of course, much has changed amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Many religious communities have had to change whether and how they meet in person for a time, to prevent the spread of infection. Many have found ways to at least partially offset this loss, moving to virtual services and webcasting, establishing online discussion groups or Bible studies, or encouraging increased personal and family devotion, prayer, and ritual. Some have even established “drive-through” prayer and confession.

Each of these is certainly better than no religious participation at all. However, none is likely to be a fully adequate replacement to the in-person meetings and community.

A recent survey by the Barna Group found that about a third of “practicing Christians” have stopped joining corporate worship altogether during the pandemic, and this group reported higher levels of anxiety and depression than those still worshiping in some fashion.

When the present pandemic has passed, it will be important to reestablish face-to-face meetings and services, rather than relying entirely on remote alternatives. And moreover, we need perspective on the real public health costs of measures to mitigate the pandemic. There’s a real cost to temporary declines in service attendance, which might lead to permanent changes in worship habits.

There is a danger here that religious leaders must consider. A huge number of churches worldwide proclaim a “prosperity gospel,” saying that Jesus will give his followers health and wealth if they only have sufficient faith (and have made sufficient “investments” through donations) to claim it.

There is no reason to think God will act in this way, based either on the Bible or our research findings. For one thing, many of the positive outcomes promoted by religious observance are not easy paths to prosperity, but ways of cultivating a spirit of hope, forgiveness, and discipline in the face of life’s many challenges. Glass’s conversion gave him new resources to cope with his trials and troubles, but it hardly offered him a winning lottery ticket.

Moreover, it isn’t clear to what extent joining a religious community actually improves the health and well-being of people who join only to promote their health and well-being, but there are reasons to suspect the benefits will not be as striking.

Consider an analogy: Marriage benefits spouses in many ways, but it does so most strongly when spouses love and enjoy one another for their own sake. So too, perhaps, with religion: As C. S. Lewis wisely observed, “Aim at Heaven and you will get earth ‘thrown in’; aim at earth and you will get neither.”

Finally, this research has implications on a more individual level. For the roughly half of all Americans who do believe in God but do not regularly attend services, the relationship between service attendance and health may constitute an invitation back to communal religious life.

Something about the communal religious experience seems to matter. Something powerful takes place there, something that enhances health and well-being; and it is something very different than what comes from solitary spirituality.

This research should challenge the growing number of Americans who self-identify as “spiritual but not religious,” or who harbor doubts about organized religion, to consider whether their own spiritual journeys might be better undertaken in a community of like-minded seekers and under the discipline of a tried and tested tradition of belief and practice.

Our research suggests that those who neglect to meet together (Heb. 10:25) likely miss something of the religious experience that is powerful, both for health and for much else as well. The data are clear: Going to church remains central to true human flourishing.

Tyler J. VanderWeele is the John L. Loeb and Frances Lehman Loeb Professor of Epidemiology at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and director of the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University. Brendan Case is the associate director for research of the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University, and the author of The Accountable Animal: Justice, Justification, and Judgment (T&T Clark).