The Middle East today is at a kairos moment in time. As women across the region fight for their rights and freedoms, the tectonic shift is felt also in Christian academia. What was once a trickle of female theologians has developed into a growing number of developing leaders, enabling and emboldening other women to rise in leadership.

While only Protestant churches have yet ordained female priests—in Lebanon, Syria, and the Palestinian territories—other similar bold figures are modeling an emerging path of spirituality within patriarchal Arab society.

But their own inspiration is found in the past.

As members of the first Christian communities, Eastern Christian women—deaconesses, historians, theologians, and martyrs—articulated their faith and theology centuries ago. However, their stories are not well known even in our region. But it is remarkable that two of the largest remaining Christian communities in the Arab world, Coptic and Maronite, have known historical female leadership. Within the rich and complex ecclesial context of the Middle East, their legacy continues to shape our theological thought as evangelical women today.

Desert mothers

Observing the full moon rise above today’s Egyptian desert in the land where Saint Anthony (A.D. 251–356) originally established monasticism as a lay movement, I am reminded how spirituality was crafted by asceticism. The desert fathers left a heritage of wisdom celebrated by many today who seek spiritual discipline.

But we often overlook the desert mothers.

These Ammas (from the original Syriac) were Christian ascetics who also inhabited the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria in the fourth and fifth centuries, whether in monastic communities or as hermits. Both men and women respected them as spiritual exemplars of maturity and wisdom, imparted through teaching, preaching, and their own sublime examples.

Edits by CT / Source Image: WikiMedia Commons

Edits by CT / Source Image: WikiMedia CommonsAmma Syncletica of Alexandria (d. around A.D. 350) led a community of women who desired to serve God, with religious insights highly esteemed in the writings of Pope Athanasius the Great.

Amma Sarah, the fifth-century hermit from Egypt’s Wadi Natroun desert, was known for her asceticism, courage, and spiritual teachings. As a well-educated reader, she was concerned that her heart be fully upright in her pursuit of God.

Amma Theodora (d. A.D. 412), a renowned spiritual guide, met Saint Anthony multiple times and was a colleague of Archbishop Theophilus of Alexandria.

Though these desert mothers desired solitude, they did not see cultural norms for women as obstacles to their calls or their pursuit of God, keeping relationships as role models in their daily study and prayerful life.

For modern-day Christians seeking to be faithful in their spiritual lives in a complex context like today’s Middle East, the core practices of desert mothers can provide rich insights. The monastic framework encourages the integration of spirituality and theology, with the Word of God and spiritual disciplines at the center.

Through times of solitude, these desert mothers produced profound theological works—lacking sorely in the Arab world today, especially those written by women.

‘Daughters of the Covenant’

Strolling down Star Street in the old city of Bethlehem today, I can see the sanctuary of the Syriac Church of the Virgin Mary. From the outset, Syriac Christianity offered women positions as deaconesses and consecrated virgins. Literary sources contain frequent references to this from the fifth century until the tenth century, in both the western (Maronite) and eastern (Assyrian/Chaldean) traditions of Syriac Christianity.

Several of the earlier texts mention the Bnat Qyama, “Daughters of the Covenant,” alongside references to deaconesses. These were women who had taken vows of celibacy and simplicity, working in the service of Christ. Not only did their women’s choirs (generally comprised of consecrated virgins) lead worship, but their hymns also provided essential instruction for believers about the Bible, theology, and Christian community. Their remarkable teaching and liturgical ministry can be traced through at least the ninth century.

Jacob of Sarug (d. 521), for example, mentioned the women’s choirs as “female teachers” (malphanyatha, in the feminine plural), whose singing declared the “proclamation” (karuzutha, corresponding to the Greek kerygma) in the liturgy. Syriac sources describe the Daughters of the Covenant, cherished for their melodious conveying of scriptural truth, as conversant with exegetical, ascetic, and hagiographic literature, demonstrating a culture where women were concerned about theological education in its many forms.

A Maronite mystic

Hannah Ajaymi was born in 1720 to a Maronite family in Aleppo, Syria. But she became known as Hindiyya due to her dark olive complexion, etymologically linked to the Arabic name for India. By the time she was 17, she was considered a model of piety in the spiritual disciplines, including oral prayer and fasting. Uninterested in marriage, she considered herself espoused to Christ.

Hindiyya’s determination to establish a religious congregation indicated her dedication to Christ, and she became the foundress and mother superior of a group of monastic women. Her first convent formed in Aleppo in 1753, but she frequently traversed the Lebanese mountains and founded four monastic communities overall.

Hindiyya was unusually well read in Arabic religious works, with a considerable collection of her own publications. Her major work, Sirr al-Ittihad (Mystery of the Union), is the first-known rare Arabic account of a mystical experience between Jesus and a Christian woman. And her Al-Durar al-Saniya (Precious Jewels) is a significant theological work—over 400 pages of spiritual counsel for her nuns. Hindiyya died in 1798.

While modern-day Lebanon struggles to rise out of ashes and debris, the contemporary Maronite church has developed room to discuss the role of women, with its 2022 synod dedicated to their particular mission. Hindiyya was revered as a saint at certain times in her life, but at other times was seen as a heretical threat to the established order. Yet as a prominent priest told me, “It is about time the Maronite church reopens Hindiyya’s file.”

Mother Irini

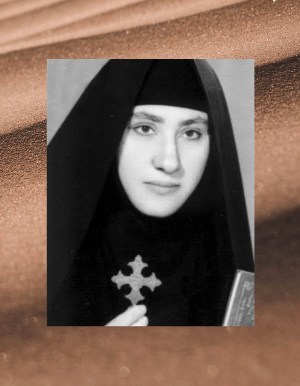

Known as Ummina in Arabic and Tamav in Coptic (“Our Mother”), Irini is a modern-day example of a desert mother. Born Erene Yassa in 1936, she became mother superior of the Old Cairo convent of St. Abu Saifein and played a major role in the revival and reformation of Coptic monasticism for women. She was consecrated as a nun in 1954 and wrote many meditations on biblical teachings, mystical visions, and physical sickness.

Edits by CT

Edits by CTFinding inspiration in the life of fellow Alexandrian Amma Syncletica, she gave up her family wealth to pursue a path of poverty. She passed away in 2006.

Mother Irini is well known and treasured by many Egyptian Christians as a female leader within the Coptic revival. Copts honor her spirituality alongside the cherished figures of Pope Cyril VI (1959–1971) and Pope Shenouda III (1971–2012).

Endowed with great spiritual vision, she employed her gifts to teach and guide both her nuns and frequent visitors—male and female—who sought out the wisdom of her monastic community. Not only did she lead a life of prayer, but she was also a gifted manager. And as the sincerest flattery for her spiritual stature, popular acclaim exaggerates her visions and miracles, similar to historic male Egyptian saints like Abanoub and Mina.

By enhancing the convent’s library with publications about godly women, Mother Irini expanded space for women in the Coptic church, where men are usually the official representatives. Renewal had previously been centered on male monasticism, but today there are hundreds of nuns and mukarrasat (consecrated virgins) in Egypt, serving the poor and recalling the traditions of ancient times.

But as mirrored in other Eastern churches, her example has inspired women outside the convents as well, stimulating renewed engagement in theological education.

Modern scholars

There are several prominent examples who follow in their heritage:

- A monastic of the Coptic Orthodox Church, Mother Lois Farag is a lecturer at Luther Seminary who authored St. Cyril of Alexandria, A New Testament Exegete: His Commentary on the Gospel of John and Balance of the Heart: Desert Spirituality of Twenty-First Century Christians.

- The young scholar Dina Tarek has produced substantial works in both biblical studies and spiritual theology through the School of Alexandria Foundation.

- Souraya Bechealany, a former secretary general of the Middle East Council of Churches, has two doctorate degrees in theology.

- Roula Talhouk, an anthropologist and a practical theologian, supervises doctoral students at Saint Joseph University of Beirut.

Marked by deep spirituality, these women are leading a new generation of female Arab theologians—within a diverse theological landscape where their presence has often been unrepresented, their voices ignored, and their contributions unacknowledged.

Edits by CT / Photo Courtesy of Lois Farag

Edits by CT / Photo Courtesy of Lois FaragIn many ways their emergence has been sparked by a Protestant egalitarian vanguard, which in turn cross-pollinates the evangelical churches with a greater respect for their historic brothers and sisters.

In the land where Christianity was birthed but where its numbers are currently dwindling, these shining female stars remind us that through the empowering of the Holy Spirit and with the prayers of the global church, the glorious gospel will continue to be proclaimed, bringing both present and eternal hope to an aching region.

Grace Al-Zoughbi (PhD, London School of Theology) is a Palestinian Christian from Bethlehem. She is an assistant professor of theological education at Arab Baptist Theological Seminary, in Beirut, and serves as an accreditation officer with the Middle East and North Africa Association for Theological Education.