There was a point in Meagan Gillmore’s life when she questioned if it was possible to be a Christian and a journalist at the same time.

In fact, the news stories that Meagan covered early in her career caused her to become discouraged and disillusioned. Wanting to encourage their daughter, Megan’s parents gifted her with a subscription to Christianity Today. CT became a lifeline for Meagan during this season of her life as she wrestled with the tension of living as a Christian while working in a secular newsroom.

Growing up in a Christian household, Meagan accepted Christ at the young age of four, but her faith truly became her own when she went on a mission trip to Greece as a sophomore in high school. She recalls visiting places mentioned in the New Testament, like Corinth or Mars Hill in Athens. “The leaders read to us from 1 Corinthians and Acts 17. This was when Scripture really came to life for me,” recalled Meagan. “It became real for me when I saw that the events in the Bible happened in real places with real people, and that Jesus actually made a tangible difference in people’s lives.”

After getting her English and Journalism degree in university, Meagan started her first job as a journalist working for the Yukon News, a community newspaper in Whitehorse, Yukon. However, when Meagan received her first assignment to cover a story about a scandal in the local humane society, she felt discouraged to be reporting on a seemingly trivial topic. “The news I was covering seemed to be mostly about what I thought were insignificant issues involving seemingly petty leadership disagreements and financial scandals, especially in light of what else was going on in the world,” said Meagan. “I was also reporting on news about people drowning in the Yukon lakes and car accidents involving drunk drivers. It felt as though my only contribution to the world as a journalist was simply to say, ‘Welcome to Yukon, that river will kill you!’” Meagan’s frustration with her work contributed to her downward spiral.

The Christianity Today subscription Meagan received from her parents came at just the right time as she wrestled with the dissatisfaction she experienced with her career. “CT was a lifeline for me during a dark season of my life,” recalled Meagan. “I was struggling to determine how to follow God faithfully in a world that ignores and derides religion, and I felt alone in my feelings. But CT reminded me that I’m not the only one feeling this way and taught me that this tension is actually a good thing. CT also showed me how I should feel about this tension, what I should do about it, and provided me with resources about how to live faithfully while working in the field of secular journalism.”

“In my experience, journalists are very aware of the problems in the world, but are not interested in a divine solution. You see a lot of grief without hope and it’s hard to talk to people who are in pain when you can’t do anything for them in your professional capacity,” explained Meagan. “Much also needs to be done to better understand and support the needs of disabled journalists, as we are few and far between. However, the bright side of being a Christian disabled journalist is that my disability gives me a reason to report on issues that reflect on how everyone is made in God’s image.”

Throughout her career, Meagan read many articles in Christianity Today about what churches were doing in their local communities. These stories encouraged her to reflect on how she could practically apply Scripture in her job. “As somebody who was spending a good portion of my week writing about city council news, CT’s articles helped me reframe what I was doing at my job,” she said.

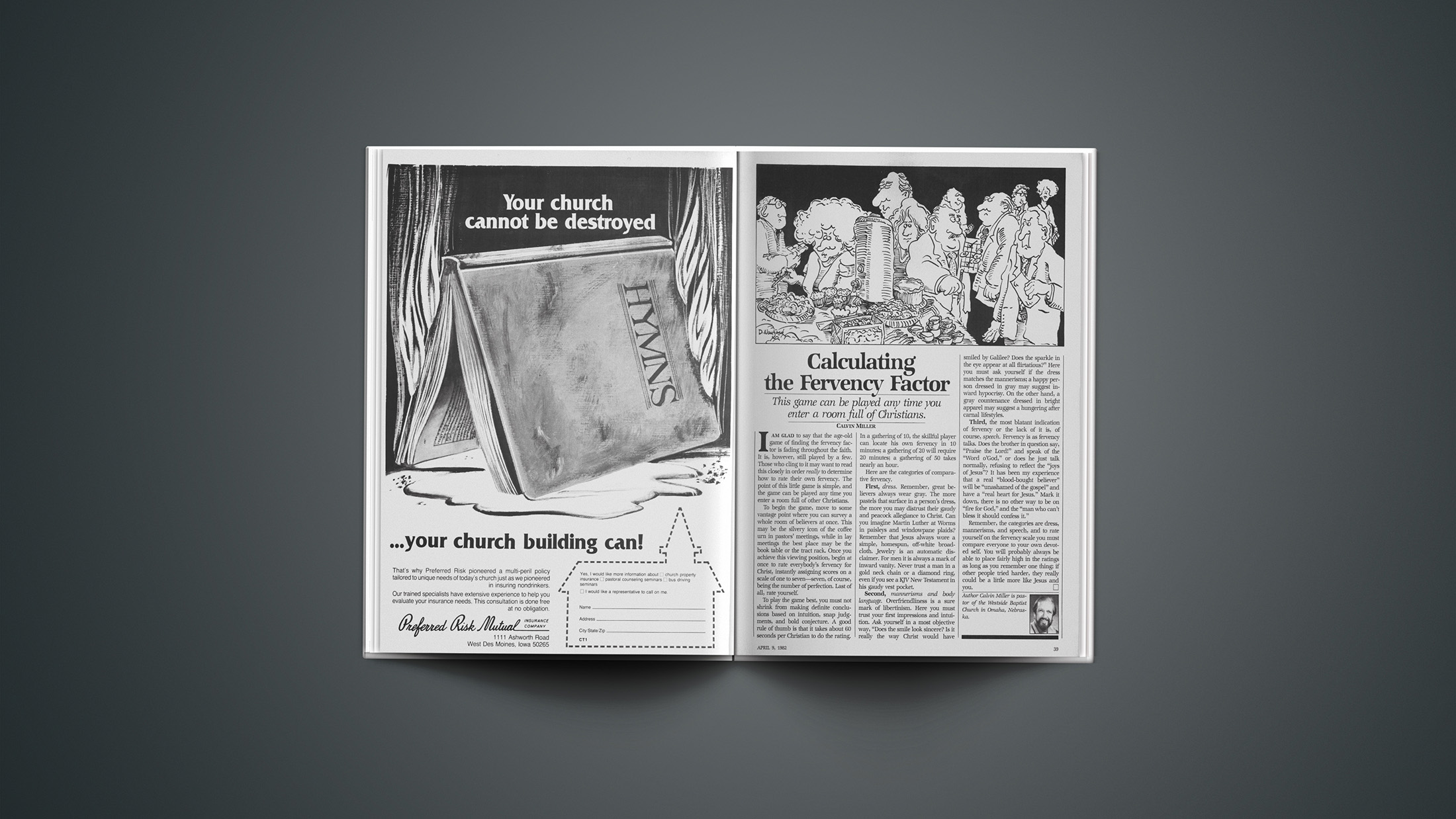

For Meagan, the most memorable CT articles are the ones that focus on the local church. “It’s really easy to complain about the church. But when I read CT’s articles about the goodness and beauty of the local church, it reminds me that Jesus is still actively using the church and is committed to her good and purity. CT’s cover story on New Life Church was the aftermath of a scandal, while the story about Snow Memorial was the aftermath of a church closure. Both those topics are sometimes discussed in mainstream media, but rarely, if ever, is the full story told.”

Currently, Meagan works as a freelance journalist and also regularly appears on radio, television programs, and podcasts produced by Accessible Media Inc., a non-profit Canadian media organization that focuses on news and current events from a disability perspective.

One particular audio show Meagan hosted in 2019 marked an important moment in her career when she interviewed a visually-impaired Jewish rabbi. During this interview, Meagan told her audience for the first time that she was a Christian. “I thought if my audience could handle a conversation on disability, they could also handle a conversation about religion,” she said. “While I was terrified of sharing my faith live on air, the first thing I wanted the audience to know about me was not that I’m a journalist, but that I’m a Christian. The Jewish rabbi and I had a lot in common due to how our disabilities impacted our individual faith journeys and relationship to our faith communities.”

“Journalists often start with ideals, or at least I did. There’s this idea that we as individuals will solve every systemic problem, but you learn pretty quickly that this isn’t true. This led me to become disillusioned about my career, but thankfully, CT reminded me that my primary identity is a follower of Jesus. This truth requires me to be part of the Church and real change will happen through God’s work in the Church. Right now, due to my job and workplace, I have some limits on how much I can fully depict the truths of the Gospel in my job. However, organizations like CT can share these truths more fully and that’s encouraging for me.”

Grace Brannon is content marketing associate at Christianity Today.