Thirty years ago, it was generally thought that conservative evangelicalism in Britain was a spent force. But this is no longer so. The editor of the 1955 edition of Crockford’s Clerical Directory, in his traditional prefatory survey of Anglican affairs, noted that “Evangelicalism has had a great revival in recent years, particularly among young people,” and went on to refer with some regret to “the growth of Fundamentalism in the universities and theological colleges.” All the Protestant denominations have been more or less affected in this way. The Inter-Varsity Fellowship and other interdenominational evangelical youth movements have grown rapidly in numerical strength since 1945. Billy Graham’s work, too, has made its own contribution towards putting evangelicalism back on the map.

For the first time in many decades, a point is being reached at which it becomes possible for evangelicals to think in terms of a planned strategy of theological advance. Liberalism seems to have shot its bolt, and Anglo-Catholicism to have lost its way; and with the impetus of both these theological pacemakers slackening, indigenous British theology is at present not far from the doldrums. The situation calls evangelicals to throw off the defensive and isolationist mentality, which has inevitably been built up during the lean years of endless rearguard actions, and to make a constructive re-entry into the field of theological debate.

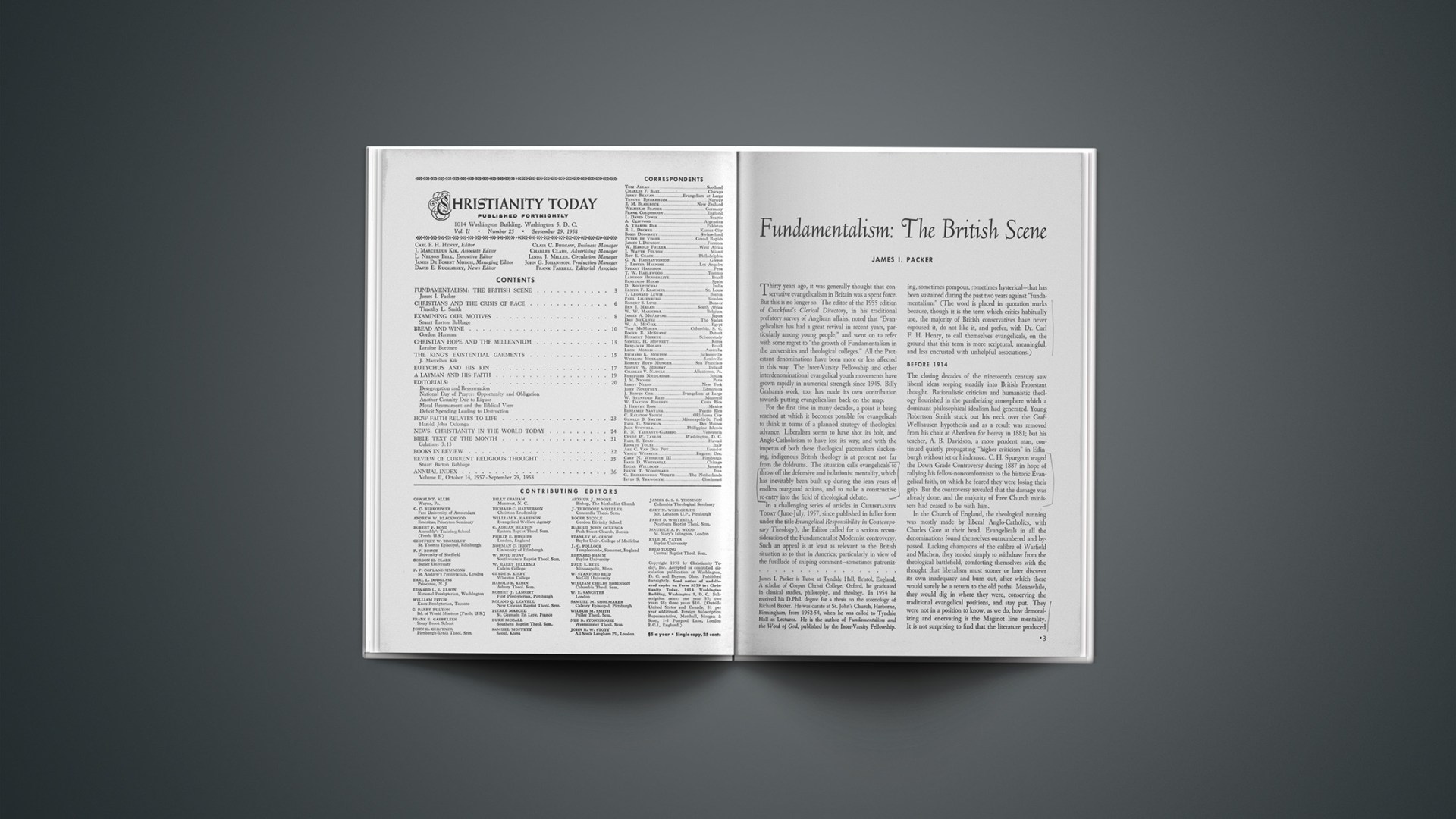

In a challenging series of articles in CHRISTIANITY TODAY (June–July, 1957, since published in fuller form under the title Evangelical Responsibility in Contemporary Theology), the Editor called for a serious reconsideration of the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy. Such an appeal is at least as relevant to the British situation as to that in America; particularly in view of the fusillade of sniping comment—sometimes patronizing, sometimes pompous, sometimes hysterical—that has been sustained during the past two years against “fundamentalism.” (The word is placed in quotation marks because, though it is the term which critics habitually use, the majority of British conservatives have never espoused it, do not like it, and prefer, with Dr. Carl F. H. Henry, to call themselves evangelicals, on the ground that this term is more scriptural, meaningful, and less encrusted with unhelpful associations.)

Before 1914

The closing decades of the nineteenth century saw liberal ideas seeping steadily into British Protestant thought. Rationalistic criticism and humanistic theology flourished in the pantheizing atmosphere which a dominant philosophical idealism had generated. Young Robertson Smith stuck out his neck over the Graf-Wellhausen hypothesis and as a result was removed from his chair at Aberdeen for heresy in 1881; but his teacher, A. B. Davidson, a more prudent man, continued quietly propagating “higher criticism” in Edinburgh without let or hindrance. C. H. Spurgeon waged the Down Grade Controversy during 1887 in hope of rallying his fellow-noncomformists to the historic Evangelical faith, on which he feared they were losing their grip. But the controversy revealed that the damage was already done, and the majority of Free Church ministers had ceased to be with him.

In the Church of England, the theological running was mostly made by liberal Anglo-Catholics, with Charles Gore at their head. Evangelicals in all the denominations found themselves outnumbered and bypassed. Lacking champions of the calibre of Warfield and Machen, they tended simply to withdraw from the theological battlefield, comforting themselves with the thought that liberalism must sooner or later discover its own inadequacy and burn out, after which there would surely be a return to the old paths. Meanwhile, they would dig in where they were, conserving the traditional evangelical positions, and stay put. They were not in a position to know, as we do, how demoralizing and enervating is the Maginot line mentality. It is not surprising to find that the literature produced by evangelicals during the generation after 1914 was almost all poor, and the impact made on the life of the churches was negligible.

Between The Wars

The fundamentalist crusade of the twenties in America had no British counterpart, although Machen’s What is Faith? aroused some discussion when it appeared in a British edition in 1925. Generally, the attention of evangelicals during these years was taken up with missions, conventions and adventist speculations. The most vigorous protagonists for evangelicalism were the conservative leaders in the Church of England. A group of these produced a symposium, Evangelicalism, which was intended as a manifesto; but it was a disappointing volume which bore no comparison with the comparable Anglo-Catholic book, Essays Catholic and Critical, which appeared in 1926.

During the twenties, the self-styled “liberal evangelical” party within the Church of England announced its arrival with two volumes of essays, Liberal Evangelicalism and The Inner Life. This group took the position that evangelicalism is essentially an ethos—one stressing the experience of conversion and personal fellowship with Cod—and that this ethos be wedded to liberal theology, not merely without loss, but with positive profit. It should be pointed out that, if one takes the word “evangelicalism” in its historic sense, as denoting loyalty to the doctrines of the Reformation creeds on a basis of biblical authority, “liberal evangelicalism” is simply a contradiction in terms. The proper name for this standpoint would be “pietistic liberalism,” or something of that nature. On the whole, however, this group has made little significant contribution to current theology, and none to the debate between authentic evangelicalism and its opponents.

The Present Position

British evangelicalism is now regaining strength, theologically and numerically. The opening in Cambridge of the Inter-Varsity Fellowship’s own residential library and research center, Tyndale House, and the growing band of scholars who work in association with this movement, are encouraging signs of the times. The evangelical resurgence has forced itself on the notice of the rest of the church and evoked a good deal of comment, as we observed earlier.

The most serious critical discussion appearing so far is Fundamentalism and the Church of God, by an Anglo-Catholic, Gabriel Hebert (1957). Dr. Hebert professes to deal specifically with “conservative evangelicals in the Church of England and other churches, and with the Inter-Varsity Fellowship” (p. 10). What he writes makes clear that in his view it is among Anglicans and the I.V.F. that the main strength of the movement lies. His book, however, though conscientiously charitable and sober, disappoints; he misses the major issues at stake altogether, and this I have tried to show in my own ‘Fundamentalism’ and the Word of God (I.V.F., 1958). Here, however, all that is possible is a brief commentary on the main criticisms which he and others have made.

The Doctrinal Debate

The chief complaint relates to the evangelical view of Scripture. Hebert describes this as belief in the factual inerrancy of biblical assertions, from which, he supposes, evangelicals infer that exegesis should be as literalistic as possible; that is to say, that every narrative should be treated as having the character and style of a modern prose newspaper-report. He is, of course, right to insist that a hermeneutical canon which arbitrarily imposes on Scripture a modern norm, rather than seeking to appreciate the narrative methods of Scripture for what they are, is theologically indefensible. But he is wrong in thinking that British evangelicals espouse any such canon. No one disputes that the Bible itself must be allowed to fix the criteria of the inerrancy to which it lays claim. Hebert here attacks a man of straw.

Moreover, Hebert’s account of the evangelical view is incomplete, and reflects a defective critical standpoint. Evidently he has stopped short at asking how far empirical evangelicalism differs from his own position, and has not considered the further question of what evangelicalism is in terms of itself. Otherwise, he could hardly have failed to notice that what is fundamental to the fundamentalism which he is examining is not one particular hermeneutical principle, but an uncompromising acceptance of the authority of all that Scripture is found to teach—including its witness to its own character and interpretation. The constitutive principle of evangelicalism is the conviction that obedience to Christ means submission to the written Word, as that whereby Christ rules his Church; whence arises the evangelical determination to believe all that Scripture asserts, as being truth revealed by God, and to bring the whole life of the Church into conformity with it.

Some excuse for Hebert’s misunderstanding may lie in the fact that during the past decades British evangelicalism has been in serious danger of misunderstanding itself. Evangelicals have thought and spoken as if the essence of evangelicalism was the maintaining of a distinctive exegetical tradition, which was itself above criticism and could be taken as a yardstick for judging the expository work of others. But such optimism, of course, is not warranted. It does not follow that, because one’s approach to the Bible is right, one’s exegesis therefore will be skillful. It may be that at some points current evangelical interpretation is inferior to that of other schools of thought. It may be that evangelicals merit some censure for their past unwillingness to criticize their own exegesis and to learn from other sources outside their own constituency. (Not that they would in that case be the only guilty parties in Christendom, by any means.) But all this has nothing to do with the question of what evangelicalism is. The most that it can show is that modern evangelicalism has on occasion failed to be true to itself. If the present outburst of criticism helps British evangelicals to see this, and to realize more clearly what kind of a position evangelicalism really is, it will do immense good.

The other doctrinal point of substance that has been raised concerns the atonement. Evangelicals are criticized for adhering to the doctrine of penal substitution. This criticism comes, not from liberals of the older school, which rejected this doctrine on rationalistic grounds while admitting that the Bible taught it, but from representatives of the modern “biblical theology” movement (notably, Hebert, the Archbishop of York, and Professor G. W. H. Lampe), who profess to reject the doctrine on exegetical grounds, doubting whether the Bible teaches it, at any rate in the form in which evangelicals assert it. (Hebert would gloss the penal idea in terms of Aulen’s “classic” theory; Professor Lampe and the Archbishop, following Maurice, think that Scripture teaches an atoning death which was representative, but not substitutionary.) The issue here, therefore, is a purely exegetical one; for “Biblical Theology,” however inconsistently, does not dispute the binding character of any doctrine taught in Scripture, except the doctrine of the unerring truth and unqualified authority of Scripture itself. To the question, whether we should hold the biblical doctrine of the atonement, Hebert and his fellows would say yes, though to the logically prior question, whether we should hold the biblical doctrine of the trustworthiness and authority of biblical teaching as such, they seem, if not to say (for they avoid the question), at any rate to mean no. It would be tempting to reflect on the oddity of this, if space permitted.

Practical Issues

Critics are generous in praising the evangelistic zeal and personal devotedness of evangelicals, but complain, with some justice, of two prevalent weaknesses in their outlook: one ecclesiastical, the other ethical. Both recognizably derive from the somewhat flabby pietism that spread through the evangelical constituency via the convention movement at the end of the last century. The effect of this pietistic conditioning was to focus concern exclusively on the welfare of the individual soul, and to create indifference both to the state of the churches and to the ordering of society. These tendencies were reinforced by reaction, on the one hand, against liberal control of the denominations, and, on the other, against the “social gospel” which liberalism purveyed as its own alternative to the evangelistic message. In addition, dispensational adventism, widely held during the first half of the century, insisted that the growing apostasy of Protestant Christendom was a sure sign of the imminence of Christ’s return, and so tended to destroy all interest in trying to remedy the situation. This type of adventism is now, if not exploded, at least out of fashion, and it is to be hoped that the apathetic pessimism which it fostered is on the way out too.

The first weakness specified may be described as the undenominational mentality. The complaint here is that evangelicals regard inter-denominational organizations as filling the center of the ecclesiastical stage. True, these profess to serve the churches; but, it is said, what they do in fact is to divert the energies of their adherents into non-denominational channels, to such a degree that worship, sacraments and service within the local congregation are crowded into second place. There seems to be some truth in this. The strength and attraction of the inter-denominational movements rest in part on the deep sense of brotherhood and mutual loyalty generated within them (English evangelicalism has happily been free from the rancorous temper and fissiparous tendencies which have disfigured parallel movements elsewhere); but this very warmth of fellowship makes evangelicals understandably reluctant to plunge back into the chillier streams of local church life and work for Christ there.

In the writer’s judgment, the reinvigorating of the local church as an aggressive witnessing community is strategic priority number one in the present British situation, and evangelicals will fail miserably if they do not direct their chief efforts to this end. In this connection, large-scale inter-church evangelistic campaigns must be judged a mixed blessing, for, however much immediate good they do, they tend to distract attention and effort away from the long-term priorities.

The second complaint is that evangelicals live in the world as if they were out of the world, showing a sublime insensitiveness to the implications of the Gospel for social, political, economic and cultural life, and shirking the responsibility of bearing a constructive Christian witness in these fields. Here, again, there is truth in the accusation. The antinomian tendencies which always hang around pietism have led in this case to a deplorable ethical shallowness; evangelicals today are not noted for personal integrity, public spirit and passionate love of righteousness in the way that (say) Shaftesbury and Wilberforce were. In this connection, perhaps the healthiest current sign is a widespread reawakening of interest in Puritan theology. This, with its profoundness and passion, its clear-cut delineation of grace and godliness, its broad world-view and consuming concern for the glory of God in all things, is perhaps better adapted than any other part of the evangelical tradition to restore spiritual depth and moral fibre to British evangelicals today.

The present revival of evangelical fortunes is heartening. But it comes at the end of three-quarters of a century of moral, spiritual and intellectual decline, during which evangelical influence in the churches and the country has grown steadily less till now it is very small; and though many non-evangelicals have recently acquired an evangelistic veneer, evangelicalism proper does not seem as yet to have regained any of its lost ground. Rather, its inner resurgence has coincided with the exertion of new pressures, ecclesiastical and ecumenical, designed to squeeze it into an alien mold and thereby terminate its distinctive existence. These pressures seem likely to increase; no doubt some gruelling years lie ahead. Our hope is that the strength of God may be made perfect in the weakness of his servants.

James I. Packer is Tutor at Tyndale Hall, Bristol, England. A scholar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, he graduated in classical studies, philosophy, and theology. In 1954 he received his D.Phil. degree for a thesis on the soteriology of Richard Baxter. He was curate at St. John’s Church, Harborne, Birmingham, from 1952–54, when he was called to Tyndale Hall as Lecturer. He is the author of Fundamentalism and the Word of God, published by the Inter-Varsity Fellowship.