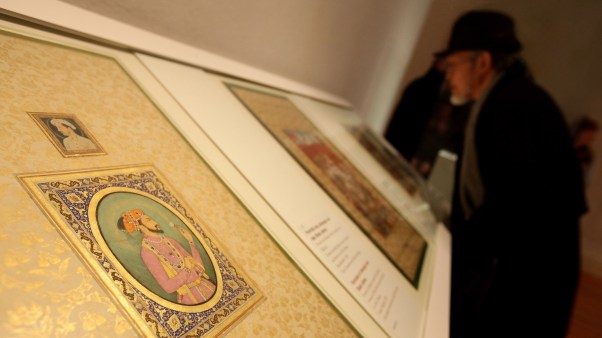

“To suppose, as we all suppose, that we could be rich and not behave the way the rich behave, is like saying that we could drink all day and stay sober.” So reads one of the choice epigraphs crowning the chapters of Lewis Lapham’s recent book, Money and Class in America: Notes and Observations on Our Civil Religion.

The quotation is attributed to L. P. Smith, of whose qualifications for social criticism I am ignorant. His common sense is, nevertheless, admirable. And Lap-ham, the editor of Harper’s Magazine, makes a good case for the intoxicating influence of money.

Lapham knows whereof he speaks: In San Francisco he was raised among “people who owned most of what was worth owning in the city”; at Hotchkiss and Yale was “educated among the heirs of certain affluence”; and in his journalistic career in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, he “met many of the people believed to have won all the bets.”

Sounding like a secular version of the French sociologist-theologian Jacques Ellul, Lapham describes the behavior of the rich as well as their spiritual and social diseases. Where Ellul describes money as a demonic “power,” Lapham calls it a “sacrament” of “our civil religion.” But both would agree, there is something about money that demands—and gets—our worship.

In the service of money, people are reduced. Writing of the rich he has known, Lapham says, “What impressed me was their chronic disappointment and their diminished range of thought and sensibility.” The rich are pampered, and (in all the wrong ways) become as little children, unable to cope with disappointment or delayed gratification. They believe that whatever they want is rightly theirs. (“Motives having to do with money or sex account for 99 percent of the crimes committed in the United States, but those with money as their object outpoint sexual offenses by a ratio of 4 to 1.”) The rich assume that everything and everybody can be valued in shekels, and thus they reduce jobs and workers to the prices they command when bid for in the trading pit.

Perhaps it is the money-induced “illusion of infinite possibility” that accounts for the sexual misadventures of the gilded class. “Among both men and women the incidence of marital infidelity rises in conjunction with an increase in income,” notes Lapham. “Of the married men earning $20,000 a year, only 31 percent conduct extracurricular love affairs; of the men earning more than $60,000, 70 percent.”

With statistics such as those, the moral lapses of nouveau riche televangelists Jimmy Swaggart and Jim Bakker leave us unsurprised.

It seems that, as Lapham and Ellul would suggest, bullion in bulk cannot be made to serve us. We can only serve it. Thus our Lord did not merely moralize about money’s proper use, but uttered a prophetic woe, warning the rich of idol Mammon’s possessive power.

By David Neff.