As I arrived at the Balm of Gilead, a palliative-care unit on the fourth floor of Cooper Green Hospital in Birmingham, one of the nurses was blowing her nose. Arnold Smith (not his real name) died that morning. Three nurses had gathered behind the nurse’s station. “When people die, it is not unusual to find the leadership team in the nurse’s station in a huddle, crying and praying,” says Edwina Taylor, R.N., nurse practitioner and go-to person at Balm of Gilead. “Our faith holds us up.”

Palliative care is not hospice care, though the two can easily be confused. Hospice care typically takes place in the dying person’s home, or in a home-like setting. According to the National Hospice Foundation (NHF), it is a team-oriented approach of medical care, pain management, and spiritual support that is tailored to the patient’s needs and wishes. Hospice care, the NHF says, upholds “the belief that each of us has the right to die pain-free and with dignity.”

The same can be said of palliative care, with a notable difference: through pain and symptom control, palliative care readies dying patients to move from impersonal institutional settings into the gentler environment of hospice care—whether at their home, in a nursing facility, or, if necessary, in the palliative-care unit itself. Dr. Amos Bailey, Balm of Gilead’s former medical director, highlights the point that “75 percent of the people who die in the United States die in medical institutions.” Fifty percent die in hospitals, another 25 percent in nursing homes. These “institutional” deaths are often painful, lonely, and isolated.

Palliative care is trying to change that picture. One might think of it as the meeting ground between hospice and institutional medical care. Situated on-site in a hospital, a palliative-care unit is a clearinghouse of sorts through which dying patients in the hospital, who have not received hospice care, get their symptoms stabilized and are then released from the hospital to die—not lonely, isolated deaths, but in a more personal, compassionate setting. Once patients have been through a palliative-care unit like Balm of Gilead, they are channeled seamlessly into the care of a local hospice.

Balm of Gilead refers terminally ill patients from all parts of Cooper Green Hospital—patients with AIDS, cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, heart and lung failure—to one of the 15 area hospices in Birmingham. Palliative care is still up-and-coming, but more medical institutions are recognizing its merit. Like hospice, it “addresses physical, spiritual, social, and emotional suffering through symptom control in those four areas for people who have a disease that man cannot cure,” says Edwina Taylor, and it makes hospice care an option for more and more patients who might otherwise die alone in a sterile hospital bed.”

Communication Breakdown

Despite the soon-to-double number of aging Americans, most don’t want to think or talk about how to die. There are now 40 million elderly people in the United States. In the next 30 years, with the aging of the baby boomers, that number will double. One third of those 80 million deaths will involve a chronic illness of some sort. Every chronic illness will require decisions, either on the part of the patient or the family. If present trends persist, most of these people will not have thought through end-of-life questions.

According to a national survey taken by the National Hospice Federation in April 1999, Americans are more likely to talk to their children about drugs and sex than about how they want to die.

- One in four people are not likely to discuss death-related issues with their aging parents, even if a parent is terminally ill and has less than six months to live.

- Fewer than 25 percent of Americans have thought about how they would like to be cared for at the end of life and have put it in writing.

- 36 percent say they have told someone about how they want to receive treatment at the end of life, but people include “passing comments” in this category. Even so, 50 percent of Americans overwhelmingly say they will rely on family and friends to make end-of-life decisions.

- Nearly 80 percent of Americans do not think of hospice as a choice for end-of-life care; 75 percent do not know that hospice care can be provided at home; fewer than 10 percent know that hospice provides pain relief for the terminally ill; more than 90 percent of Americans do not know that hospice care is a fully covered Medicare benefit.

The NHF calls it a national “communications challenge.”

Hospice care has come a long way since its inauspicious beginnings in the late 1950s in Britain. More than 40 years later, 3,000 programs have been launched in the United States and more than 450,000 patients have sought hospice care in their last stages of life.

Making more people aware of the benefits of hospice care has been a challenge. The medical establishment excels at curing people and is hard-pressed to surrender to death, which smacks of failure. This reticence also sometimes leaves patients ill-equipped to face their final days. A recent study conducted by the University of Chicago found that nearly 40 percent of the 258 doctors surveyed said they “would knowingly give inaccurate estimate of survival time, even if the patient had specifically asked for a frank prediction. Most doctors erred on the side of optimism” (Chicago Tribune, June 19). But beyond institutional resistance, the pragmatic youth-oriented culture we live in also works against having this conversation.

Balm of Gilead is among the first palliative-care units in the nation trying to change the tide. And only Balm of Gilead has worked with local Christian churches and other religious groups to help make it work. The small cadre of pioneers on Cooper Green’s fourth floor are linking the medical establishment with the hospice movement and inviting religious believers to join in. More and more, Balm of Gilead and other palliative-care units are getting those 75 percent of patients destined to die in impersonal institutions into the hands of someone who cares about their pain, their families, and their spiritual life. Like the words of the black spiritual for which it is named, Balm of Gilead stands behind this truth: “There is a balm in Gilead that makes the wounded whole.”

A Rebel Movement

Amos Bailey notes that hospice care was “an antiphysician movement” in its beginnings. In the 1940s a British “almoner,” or patient’s advocate, named Cicily Saunders (now Dame Cicily) had witnessed the difficult isolated deaths of terminally ill patients, and her heart was moved. She felt a calling to serve and help them. She spoke to a trusted friend, a physician, who told her, “Go study medicine. It is the doctors who desert the dying.” She completed her medical degree in 1957 at the age of 39, and after much prayer and meditation came up with a plan. St. Christopher’s Hospice was born in 1967 in a London suburb, and with it the hospice movement.

Those renegade beginnings account for some of the languid response to hospice by the medical establishment. “Physicians and traditional [medical personnel] weren’t paying attention to those who were dying,” says Bailey. “They weren’t very involved and were happy not to be involved, at least initially. It was primarily nurses and other support people who were dissatisfied with the kind of care that dying people were receiving. In reaction to that, they decided they didn’t want to be in hospitals. Cicily Saunders opened a residential unit [in a hospital]. But we don’t have very many of those in the United States. We have primarily home hospice programs.”

But the hospice movement’s “antiphysician” roots explain only part of the medical profession’s sluggishness. The starting point for hospice care is the abandonment of hope for recovery. This starkly contradicts a medical institution’s curative approach. “Physicians see a dying patient as a defeat, like they didn’t do their job,” says Edwina Taylor. “They emotionally withdraw from them.”

Adds Bailey, “People [in the medical community] feel powerless and don’t know what to do. Studies have been done where they put cameras in front of the doors of rooms of patients who were dying. As the person got sicker, fewer people went in. And when they went in, they stayed for shorter periods of time. It’s very uncomfortable. If they can’t help this person, then being in the room with them and spending time with them is unpleasant. They don’t want to be in that situation.”

Hospice and palliative care—in addition to managing physical symptoms—also rally around the emotional, social, and spiritual aspects of dying, areas for which the medical community has not presumed expertise. Bailey, Taylor, the small Balm of Gilead staff, and their army of volunteers are making the case to the medical establishment that all of these aspects are essential to the human condition and need to be integrated into the dying process.

Lessons from ‘the Last Hours’

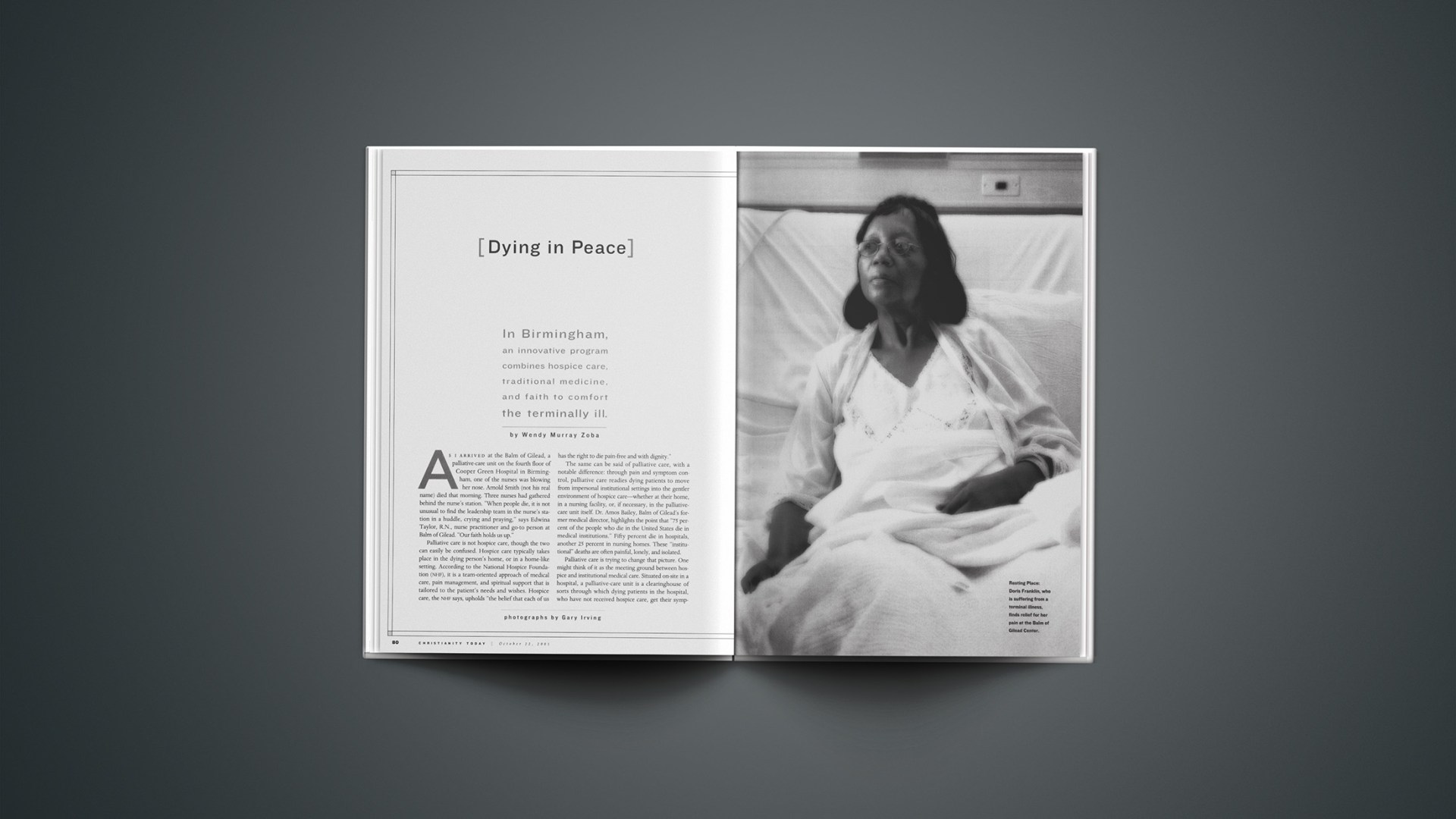

Birmingham has been called “the Pittsburgh of the South,” an old rust-bowl steel town with a high unemployment rate and lots of people on welfare who can’t afford medical coverage. Early in my visit, I chatted with Miss Sunday, an African-American nurse sitting behind the glass encircling the nurse’s station. Behind her on the window are sunny images of flowers, bumblebees, and trees. A sign reads: IT’S SPRINGTIME AT THE BALM OF GILEAD. She is a jolly dumpling of a woman who tells me, “We don’t hear about many [dying] people who have loved ones at home. They really need help and don’t have a clue where to get it from.” The majority of terminal patients who come to Balm of Gilead, 70 percent, are minorities and poor. Many don’t have health insurance.

Miss Sunday hands me a chart. It lists the churches that sponsor rooms at Balm of Gilead. Her church, Faith Apostolic, sponsors Room 417. That means church members set up the room with cozy furniture, including a comfortable sleeping chair for family, and a TV/VCR (about $5,000). They also oversee the steady flow of volunteers who water the flowers, put together care packages for the patients, play the guitar and sing, or sit and hold the hands of the dying in Room 417. The sponsoring church or community group “owns” a room. There are ten such rooms at Balm of Gilead that serve approximately 200 patients a year.

Miss Sunday is one of a paid team of five at Balm of Gilead, which has no secretary or copy machine. She is a busy person. They all are busy in that hallway. I thank her for her time. “We’re happy to entertain, mmm hmm,” she says.

About an hour later, I am sitting off to the side in a meeting room on Cooper Green’s eighth floor. Medical students, interns, and residents have gathered around the meeting table for the “Morning Report.” Their shirts and ties are hidden under white coats and green surgical outfits. They have stethoscopes around their necks. Some are sipping Pepsi or coffee from mugs.

These doctors and doctors-in-training receive four 15-minute sessions daily from various specialists who work at the hospital. I am sitting in on Bailey’s session. It is up to him to help these students get their heads around this notion of holistic end-of-life care. Most will not know what palliative care is. Medical schools do not teach it. Today’s discussion is called “The Last Hours of Life.”

“Mr. Smith has small-cell lung cancer. He is in the active dying process,” Bailey begins. “What are the symptoms of someone who is actively dying?”

There is a flurry of response:

“Pain.”

“Secretion.”

“Dyspnea.”

“Drying of the membranes, eye and mouth.”

“Depression.”

Bailey is discussing what a doctor can do for a patient who has entered the active dying process. He is trying to help these students understand that doctors do not have to throw up their arms, shut the door, and walk away from a dying patient. “Doctors write orders,” he tells them. “I want you to be able to write orders better.”

Bailey is an Episcopalian who wears a bow tie with earthy cottons, reads Sojourners, and speaks in soft, measured intonations. He is a kind man, unharried by the unrelenting demands foisted upon him from students, interns, and residents, as well as the dying. He is strongly fixed on his sense of calling. He lives to relieve the suffering of dying people.

He was born and raised in rural Florida, the first of his family to graduate from high school. He put himself through college on an accelerated schedule and knew he wanted to go to medical school, though he couldn’t decide between psychiatry and internal medicine. He chose the latter, with a specialty in hematology and subspecialty in oncology. He completed a fellowship at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), where he caught his first glimpse of the serious gap that existed between medical care and the treatment of the dying. “I saw lots of unrelieved suffering and didn’t have a clue about what to do about it,” he says.

Upon completing his training, he moved to Appalachia, in West Virginia, where he practiced internal medicine and oncology among the rural poor. “Everything I learned about palliative care, I learned from those experiences,” he says. Self-taught, he gained firsthand training in end-of-life care and became the medical director of a hospice that served low-income mountain people, bringing to bear all aspects of well-being (emotional, social, and spiritual with the physical) to his medical care. Many of his patients were homebound, so he began making house calls, a practice that he continues today. He also stepped into the void among physicians willing to treat patients with HIV.

Bailey returned in 1994 to the UAB’s Cooper Green Hospital, where he now practices as a medical oncologist and supervises medical students and residents. He is Alabama’s first board-certified physician for hospice and palliative care, and he was recently elected to the Fellowship of the American College of Physicians. Married and the father of three, he builds birdhouses his daughter designs when he is not training the residents or adjusting the MSConcentrate levels of the dying.

Morning Report participants had no difficulty rattling off the symptoms that attend active dying. Knowing how to best serve the patient was more of a challenge. Bailey drew a road map. Doctors can actively treat and participate in the dying process of a patient, he wants them to understand, and there is a way of doing it that hands patients the controls and helps and comforts them. “We want to get away from IVs, NG tubes, restraints, oxygen masks, and isolation from family,” he says. “There is a way of treating Mr. Smith that doesn’t use these things. These really don’t help people.”

He goes back over the list of symptoms. For Mr. Smith’s pain, “we decided not to use MSContin and use MSConcentrate instead. It goes under the tongue, so he doesn’t have to swallow.” It helps Mr. Smith to take medication that dissolves under the tongue.

“For the secretions, we put a Scopolamine patch behind his ear. That gets rid of the death rattle [a gurgling sound produced by mucus in the lungs of a dying person]. The death rattle, actually, is more of a concern for the family than the patient. It is very uncomfortable to listen to. It drives families away.” Scopolamine helps Mr. Smith not to drive his family away.

“For the Dyspnea [labored breathing], an O2 nasal prong, as tolerated, as he wants it.” Mr. Smith determines how much he can tolerate.

“For the drying of the membranes of the eyes, we can give him saline eye drops. You can assign this to the families. They want to do things.” It helps Mr. Smith and his family to participate in his care.

“Depression is often associated with the family. Yesterday, in the throes of death, Mr. Smith was holding on to see his daughter one last time. But she refused to come. She didn’t want to see him dying. We had a chaplain come.” Mr. Smith’s pain was eased by caregivers who recognized his need for spiritual, as well as physical, care.

Bailey concludes his 15-minute presentation with an appeal for the students to read “Gone From My Sight,” a booklet that outlines for patients and family what to expect in the last stages of death. “It only takes a few minutes to read. Families will read it over and over again. Hospice workers have put this together over many years. It is very reassuring to the patients and families if you know what they’re concerned about and bring it up. It shows expertise on your part. It shows concern.”

He lingers after the session to chat with students. “It was an incredible flail, trying to get his feeding tube down,” one student says of a patient. “He goes in and out a lot.” Bailey tells that student, “If he’s delirious, just give him at least one scheduled dose.”

We are walking down the hall on our way back to the fourth floor and Bailey is stopped constantly in the hallway. I feel like I’m in the presence of a rock star. Students are lined up to speak with him. He looks at the chart one student presents to him. “You’ve got this right, but that wrong,” he says.

(Since my visit to Balm of Gilead last spring, Bailey’s role has changed. Though he still instructs students at the center, the program’s success has given him the chance to develop a new palliative care unit at the nearby VA hospital. The program launches in January.)

A Heart’s Cry

Controlling physical symptoms is only the beginning of palliative care. “We actually think that one of the worst deaths people can have is spiritual, when people are in spiritual anguish,” Bailey says to me as we sit in his office. “We had a guy who was having nightmares about the fact that his family was religious and he wasn’t. He had had a problem in his marriage and felt unforgiven. He said he wanted to be baptized. We arranged for a minister to come up who told him he could be sprinkled. But he wanted to be completely immersed. They were a Baptist family. So we filled a bathtub and let the minister baptize him.

“We had somebody who died this last week who was afraid of dying. I asked her what she thought happened to people when they die and she said, ‘I think you just stop being.’ She had lived a wild life. Then she became ill and started going to church. She tried to believe. But it was impossible for her to feel reassured by that. It caused tremendous struggle, hollering, and twitching.”

“It was awful,” adds Taylor. “It went on for days. We gave her very potent medicine to try and calm her down. She felt a little calmer but never got peaceful. Her life was just horrible, apparently. She had so much that was unresolved, it all came back to haunt her on her deathbed.”

Taylor’s defining color is red: her short, smartly clipped hair is red; so are her flowing knit dress, apple-shaped earrings, and lipstick. The color sets off her brilliant eyes, which shine when she smiles and when she cries. If Bailey embodies the gentle calm of symptom management and compassionate care, Taylor is the fire that burns in the heart of Balm of Gilead. Her “heart cry” is that no person dies alone and unresolved.

Later in my visit, we are sitting in her small, cramped office. Her desk is covered with papers and books and family photos of her two grown children. “When a person dies, it takes a whole lot of pulling together,” she says. She outlines for me, in four aspects, how this heart cry plays out in that hallway.

The first is what she calls the power of presence. “Write that in Second Coming headlines,” she says to me. “You don’t abandon people. Nobody wants to die alone. Jesus said, ‘Lo, I am with you always.’ There is nothing greater than that. You don’t have to say anything profound. There aren’t enough profound things to say. But if you don’t have to suffer alone, you can kind of do it.”

Second, affirmation of family. Integrating family members into the dying process is critical. It allows the dying person to find resolution and release, in order to leave this world in peace. But bringing family into it can be “very messy,” she says. “When a terminal illness occurs, all the problems in the family are magnified a thousand times. It is very difficult. We have families who haven’t spoken for years. So we’re treating the patient’s symptoms, while working with the families all at the same time. It’s like the Nike thing: You just do it. You don’t do it right all the time. But you have to do it.”

Third, explain, explain, explain. “We had a difficult death last week. I told the same story 16 times.” The pain and shock of watching a loved one die leaves a family disoriented. Being willing to explain what’s going on over and over again, she says, “enables people to move through the grieving.”

Bailey told me about a patient who, in the months preceding death, was in and out of Balm of Gilead for an array of symptom-control problems. One of the complicating factors was the family, which for a long time refused to accept the gravity of her condition. It took repeated, often painful, conversations with Bailey before family members could come to terms with how to help their loved one.

At one point the patient was having trouble swallowing because of multiple strokes: “She couldn’t swallow and had a feeding tube and kept getting congestive heart failure,” Bailey says. “They would try to get rid of too much fluid, and then she’d have renal failure. Then they’d give her more fluid. It was flail back and forth, back and forth. Every time she’d come in, the house staff would say, ‘Dr. Bailey, you have to talk to this family.’ I’d go talk to them and they would be angry and yell at me and say, ‘She’s not really dying. She’ll live.’ They wouldn’t accept it. I would go back a couple of months later and we would start the conversation again. Eventually they took her home and, eventually, she died peacefully. We just have to be sticking with her.”

Being vigilant in explaining, Taylor says, “signals the family that you know what you are doing and that you are doing everything you can to relieve the suffering of their loved one.” Often in the “explaining” stage she finds the opportunity to introduce a spiritual witness. She said to a mother whose son died of AIDS, “God knows how you feel. He watched his Son suffer and die, too.”

Fourth, physical and emotional touch. “We can touch people at some point in the human experience that we hold in common,” she says. “I don’t do boundaries.” She told me about a crack addict they had in the hallway who was unruly and difficult, someone they all had to buck up to care for. As she drew near to death, they heard her say, “I think I’m going to die. I need to go to the bank to get money to buy shoes for my baby.” This window into her soul opened up for the beleaguered staff a new compassion for this woman. “God is here,” Taylor says. “He gives us his mercies and grace every day.”

The phone rings. It is a worker from a local hospice calling to check on a breast-cancer patient at Balm of Gilead. Edwina tells the caller, “Well, she’s not out dancin’ in the halls, but she’s not screamin’ either.” She put the receiver on the desk and went to check on the patient while the caller waited. After she hung up, Taylor told me the breast-cancer patient “will have to go into a nursing home, but hospice will follow her there.”

Going Home

Some have wondered if hospice, being a Medicare benefit, might open up greater possibilities to legalize physician-assisted suicide (PAS) to keep costs down. Bailey demurs. “People who have primarily availed themselves of this are white, middle-to-upper-class educated men, who have the illusion that they are in control—women and minorities and poorer people learned the lesson long ago that they’re not in control. It is almost never because of poorly controlled symptoms. If anything, [PAS] has spurred the improvement in symptom management and pain control and the attention given to the dying.

“This is not rocket science,” he says. “But people don’t know about it.” Several institutions have shown an interest in developing palliative-care programs and representatives from a number of Alabama hospitals have visited Balm of Gilead. It was also featured in a four-part Bill Moyers PBS special called On Their Own Terms, and there is an increasing literature available about how hospitals can introduce it into their programs.

Balm of Gilead is supported by a number of organizations, including the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Initiative for Excellence in End-of-Life Care, Cooper Green Hospital, and the Jefferson County Department of Health. It also has partnerships with local foundations, colleges and universities, faith communities, and civic and professional groups. Between November 1998, when Balm of Gilead opened, and July 2000, 347 patients died at Cooper Green Hospital. Of those, 180 (nearly 52 percent) had been moved to the palliative-care unit. Nationally, only 15 percent of Americans take advantage of palliative care or hospice services).

“People don’t have to have crummy end-of-life care,” says Bailey. “It’s like the physician that doesn’t know what to do. Well, patients and families don’t know what to do either. And no one is there to help them, so they just muddle along. That’s why people end up in ICU, when what they really need is to spend time in a room where their family can be with them.

“People think that to die you need a good doctor, a good nurse, a good social worker, a good chaplain, and maybe a good mental-health worker,” he says. “I don’t want to downplay that, but quite frankly, what people need is to stay connected with their community and their families. Instead, we take somebody who gets too sick to stay home and pluck them out of bed and put them someplace where you can only visit them a couple hours a day. And even that is not convenient, because it is during working hours when nobody can get there.” (Balm of Gilead has no limits, for persons or hours, on visitation.)

“You’ve taken them out of their community and want ‘professionals’ to care for them when what people really want is to be with their family. The medical system does a terrible job. It doesn’t know what to do.

“Professional caregivers can help, but this is something bigger. What people really need when they are facing death are five things: To say, ‘I forgive you. Please forgive me. I love you. Thank you. Goodbye.'”

Wendy Murray Zoba is a senior writer for CT. For more information about Balm of Gilead, call 205.918.2332, or visit www.gileadcenter.com.

Copyright © 2001 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

A ready-to-download Bible Study on this article is available at ChristianBibleStudies.com. These unique Bible studies use articles from current issues of Christianity Today to prompt thought-provoking discussions in adult Sunday school classes or small groups.

The Balm of Gilead is a comprehensive program for end-of-life care supported in large part through funding from the Initiative for Excellence in End-of-Life Care of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Resources for hospice and palliative care include:

- The Center to Advance Palliative Care is a resource to hospitals and health systems interested in developing palliative care programs.

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine is the only organization in the United States for physicians dedicated to the advancement of hospice/palliative medicine, its practice, research and education.

- The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care offers an online manual on palliative care.

- National Hospice Foundation gives tips on selecting a hospice program and communicating end of life wishes.

- American Hospice Foundation has helpful articles for those who are dying or grieving.

- National Hospice and Palliative Organization gives access to extensive resources and links.

- Hospice Foundation of America has resources on sudden loss.

Progress in Palliative Care is a multidisciplinary journal with an international perspective that provides a forum for rapid interchange of information on all aspects of palliative care.

In 1998, Christianity Today looked at fears that a bottom-line mentality, had “hijacked” the original hospice vision of the movement’s Christian founder, Cicely Saunders.