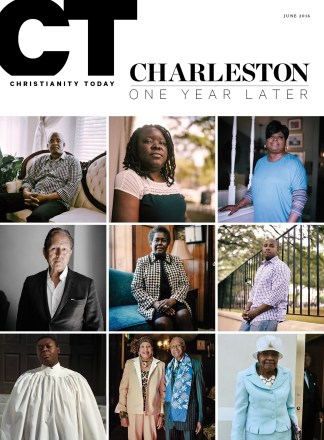

In the short film The Psalms, Eugene and Jan Peterson welcome an unusual visitor to their lakeside cabin in Montana—Bono.

Peterson is the author whose Bible paraphrase The Message has sold millions of copies. Bono is a global activist who sings with an Irish rock band. The two sit together at a table, sipping tea and talking about their shared love of the psalms. Watching them interact is like seeing “a 12-cylinder Maserati next to a horse-drawn carriage,” says the film’s producer, but the contrast is what makes the conversation so interesting.

“Is it a mash pit?” Peterson asks, recalling his first U2 concert.

Photo by Taylor Martin

Photo by Taylor MartinAs Bono and Peterson converse, the camera cuts now and then to the producer’s far less recognizable face—a man in his early 40s asking questions and nodding. His name is David Taylor; he’s an assistant professor of theology and culture at Fuller Theological Seminary’s Houston campus.

At first glance, the film simply offers two celebrities chatting about music, mosh (not mash) pits, and the psalms. But for Taylor, the two men embody his own long-term mission. Bono’s music is infused with biblical passion, while Peterson leads with the soul of an artist and writes with the soul of a poet. Cultivating those kinds of artists and pastors—and kindling friendships between them—is the heartbeat of Taylor’s work.

Although the church has made strides in the past few decades to revive its historically rich relationship with the arts, many congregations still strain to bridge the divide between artists on one side and pastors and worshipers on the other. Artists often speak and work in ways remote from mass culture and everyday experience, while many Christians find avant-garde art uninteresting and unrewarding. Taylor wants to draw the two sides together.

Photo by Ken Fong

Photo by Ken FongProfessor and Prophet

The first time I go to meet Taylor at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildlife Center, Austin, Texas, I can’t find him. It turns out that he’s hiding in his car in the parking lot making last-minute additions to his notes before his public lecture. When he finally comes in from the cold winter night, he shows me his necktie, covered with blue scribbles. “My daughter, Blythe, made it for me,” he says, holding it proudly in his palm.

At the time, Taylor was sporting his signature red beard, which he grows out and shaves off now and again. As the beard comes and goes, Taylor looks like either a mild-mannered professor or a wild prophet. In fact, he is both: an unconventional arts leader whose calling is to reinforce the establishment of the church.

“My aim is to make a case,” he says that night from the podium. “The visual arts . . . enable us to see the world as God sees it. Our sight is broken and needs mending. Artists come along and say, ‘Hey, I can help.’ ”

Halfway through the lecture, Taylor displays a photo of a multimedia piece called The Chancel, built from panels of plywood interlaid with paint, gold leaf, and obscured Scripture passages.

“This work intends to give visual expression to the resurrection of Christ,” he says. “How many coats of paint?” he calls out to a woman in the crowd.

“Maybe 80?”

“I usually give this talk when she’s not around,” he chuckles, “so I better get it right.”

The woman, it turns out, is Phaedra Taylor, an artist who has produced commissioned work for churches across the country, from City Church in San Francisco (Reformed Church in America) to All Saints in Durham (Anglican). Although David is the more public figure of the two, he and Phaedra both seek to enable “art making by the church, for the church, for the glory of God in the church, and for the good of the world.”

The Taylors’ work takes them inside concentric circles of conflict. Looking outward, Western Christians face an increasingly un-churched culture, in which art is one of the last remaining sources of transcendence and reverence (observe the hushed devotion in many museum galleries). But its leading practitioners tend to be irreligious, sometimes stridently so. Some Christians looking for a toehold in the secular world see the arts as a surreptitious way to bridge the sacred and the secular. Others reduce art to a means to an evangelistic end—“produce a film, and they will come.” Still others view art as a shallow distraction from the work of preaching the gospel or alleviating poverty.

The Taylors aim to hold together two principles that offer a better way: excellence in the arts and inclusion in the arts. What we see on Sunday—whether a song, a pageant, or a painting—should reflect the glory of God and the created order. But art happens in community, so both the mechanic and the art critic should be able to participate somehow, as producers, patrons, or enthusiastic viewers.

This democratic vision grows out of the Taylors’ sensibilities and their shared calling. Indeed, if you were looking for the next generation of leadership for the church and the arts, you might look for a pastor who loves artists, and an artist who loves the church, and arrange for them to marry one another.

Serious Business

The son of church planters with the Central American Mission, David spent most of his childhood in Guatemala amid death squads and Marxist guerilla movements. After his family moved stateside in his early teens, he was studying for a career in the Foreign Service when he read Chaim Potok’s My Name Is Asher Lev, which prompted “an awful ache to make art.” He went on to study theology and New Testament at Regent College, spent nine years as a pastor at Hope Chapel in Austin, Texas, and completed a doctorate in theology at Duke Divinity School.

“I’ve been interested in worship ever since I was a kid,” says David. “But it wasn’t until pursuing my doctorate that I decided to make liturgical theology my main area of study. I realized, good grief, I’ve been following the trail on this worship thing for the last two decades of my life, but I had been haunted by a feeling of embarrassment that it wasn’t cool enough or substantial enough. After discovering liturgical scholars, I thought wow, this is serious business, and it’s been the business of the church for 2,000 years.”

The campus of Fuller Texas, where Taylor has taught for two years, is situated in a 1970s-era business park on the outskirts of Houston, an oasis in an otherwise sterile corporate setting. The day I visited the seminary, David showed his students a rough cut of the Bono and Eugene film. An audio glitch delayed the showing, but when Bono finally came on screen, the students leaned in to hear him say in his iconic Irish accent what David teaches almost every day: “The only way we can approach God is . . . through metaphor, through symbol. Art is essential, not decorative.”

“When I talk to both my Presbyterian friends and my Pentecostal friends,” says David, “they ask, ‘Why should we care about [art]? Where is it in the Bible?’ God has designed us to take joy in making stuff with the creation and then making sense of that stuff. The arts are a fundamental way to be human. They’re rooted in the work of the triune God.”

David is drawn to churches that don’t have strong arts backgrounds. “When I began my work as a pastor, I regarded the church as my enemy and people as stupid because they didn’t understand the arts. If the church could just get its act together, I thought, then everything would be fine. Eventually, I felt thoroughly convicted. This is the bride of Christ. Let’s assume that people can understand and appreciate art. Let’s meet halfway. ”

After that change of heart, David spent nearly 10 years helping people “meet halfway,” pushing artists toward churchgoers and churchgoers toward artists. On one side, he challenged Hope Chapel to patronize the arts, attend gallery openings, and actively take interest in the work of Hope’s artists. One Sunday, professional modern dancers led the congregation in movement. Another week, David led a discussion on how to think about horror films.

“After the discussion, no one had any interest in watching horror,” says David, laughing. “But people understood what horror movies were all about, artistically and theologically.”

Meanwhile, David challenged Hope’s artists to serve the church by running a film festival, co-teaching Sunday school, and creating five art exhibits that rotated to the beat of the church calendar. On one occasion, they suspended a thousand beeswax-soaked paper butterflies from the sanctuary ceiling. The installation was an allusion to Matthew 5:45, that God’s mercy falls on both “the righteous and the unrighteous.”

“I met with the artists on a regular basis,” says David. “I would ask them, how are you doing spiritually, relationally, and artistically?” He invited artists into small groups and encouraged them to volunteer in the nursery, because, “as a member of the body of Christ, you get to serve the church, whether or not it has anything to do with art.”

Years later, David follows the model he developed at Hope Chapel as he teaches music pastors, preaching pastors, and pastors-in-training at Fuller Texas. One of those students is Jeremiah Situka, a second-generation Ugandan immigrant who works on staff at a local Presbyterian church and leads mission trips to Uganda. When I asked him how David’s ideas shape his work, he leaned in and talked at length.

“I don’t just depend on the worship leader anymore; I can collaborate with the worship leader,” he said with enthusiasm. “Now I have tools. I can have a conversation [about the arts]. I can look at how Scripture forms and informs worship.”

Drawing together artists and pastors is exactly what David is working toward. “It comes back to virtue,” he says. “Artists can serve the church by being humble and generous and brave and patient. They can serve by volunteering on a committee or consulting on a project. On the other side, leaders can come alongside artists and say, ‘I’m not sure I get what you’re doing, but I love you. Help me understand your work. Tell me how I can support you.’

“In the end, all of us—pastors, artists, and parishioners—need to be full of the fruit of the Spirit.”

Art for the Hope of the World

“I’m sorry about my clothes,” says Phaedra, referring to the tunic pajamas she’s wearing. It’s almost noon. I follow her up the central stairs of her and David’s home and into an attic washed in late-morning light. She shows me various work stations, an art table for her 4-year-old daughter, and, at the back of the room, a table for encaustic or hot-wax painting that involves beeswax. “I have a bee problem,” she says, pointing to the scattering of dead bees on the windowsill. “They’re attracted to the beeswax. I feel bad for them.”

Photo by Holly Fish

Photo by Holly FishPhaedra’s open congeniality mirrors her philosophy of art: she wants not “art for art’s sake” but rather art that serves her neighbors. “So many people feel rejected by art,” she says. “They think, ‘I’m not good enough or smart enough or cultured enough,’ and then they walk away. There’s an idea in the contemporary art world that you don’t want to make art too easy or obvious, but it’s a terrible idea. I want to offer people a way in. I have to ask, am I making art for other artists or art for people?”

Raised in Aberdeen, Scotland, in a Jehovah’s Witness family, Phaedra converted to Christianity while studying sculpture at the University of North Texas. After two art internships, she married David, started selling encaustic crosses to help pay the bills, and ran headlong into a vocational crisis.

Courtesy of Phaedra Taylor

Courtesy of Phaedra Taylor“After school, there was this push to make art that was relevant and edgy, but I was painting crosses and writing out Scripture,” says Phaedra. “I struggled. At some point, I had to die to my pride and realize that I wanted to make art for the people of God. I love the church. I think she’s the hope of the world. Why wouldn’t I want to make work for her?”

One of her first commissions came from Church of the Apostles, an Anglican congregation in Raleigh, North Carolina. Rather than isolate herself, she involved the congregation in the project by making 1,200 flame-shaped paper cutouts on which individuals wrote Lenten prayers. After praying each prayer aloud while bent over her studio table, Phaedra layered the prayers into the burning wax of two large encaustic paintings that hung at the back of the sanctuary. It was a visible reminder of Lent for the hundreds of people who passed by. Although Phaedra has produced nearly a dozen commissioned pieces of “liturgical art,” she exhibits her work in contemporary galleries and believes that all art, regardless of its setting, belongs to God.

For all her optimism, however, Phaedra is troubled by the ongoing tension between the art world and the ecclesial world. At a recent conference, she saw young artists who were averse to

Courtesy of Phaedra Taylor

Courtesy of Phaedra Taylorproducing “lay-friendly” work. In their fight to survive in an often-hostile secular setting, says Phaedra, they sometimes end up producing things that are esoteric and inaccessible. Along with David, she feels called to come alongside these artists by creating a safe space for them in the sanctuary, encouraging them in their work, and pushing them to cultivate generosity toward others, especially those they see as “less artistically minded.”

After all, the church traditionally has a lot to offer: patronage, a built-in audience, and an integrated vision of art and faith.

“I didn’t grow up in the church, so to me, it’s such a precious and powerful thing,” says Phaedra. “If [artists and churchgoers] could figure out how to be in community with one another, it would be spectacular. The church is an incredible resource.”

Stuff and Glory

In the spring of 2015, David helped organize a retreat at Laity Lodge for a group of high-profile arts leaders from across the country. In their first meeting, they taped easel paper on two walls of windows and spent hours scrawling a brief history of Christian engagement with the arts over the past century, from C. S. Lewis and G. K. Chesterton to Francis and Edith Schaeffer, who started L’Abri in the 1950s, to Charlie and Andi Peacock, who established Art House America in the 2000s. The final meeting looked forward instead of back, asking: Where are we headed, and who is taking us there?

David facilitated the meeting that morning, a detail both minor and revealing. Of the key players in the room, he was the only one under age 45. The cracks of the conversation exposed a vague uncertainty about the future, along with the need for more young leaders at the national level who, like the Taylors, are actually producing art, mentoring artists, and teaching a robust theology of art.

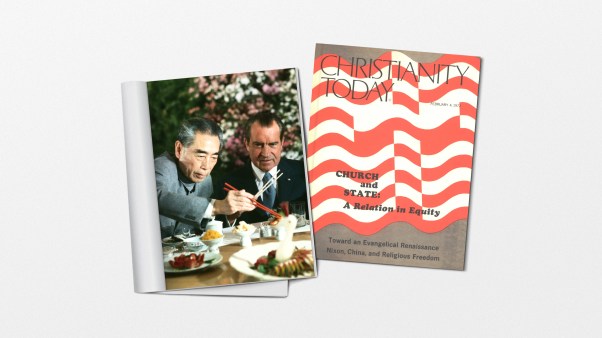

For now, the Taylors are carrying the torch. Their influence is subtle, but ask around in the Protestant arts community, and their names are mentioned frequently—most of all in reference to their ever-expanding web of relationships. From headliners like Bono to no-name artists, from big-name leaders like Peterson to small-town pastors, the Taylors have a special genius for gathering them all together under the canopy of the worshiping church.

“In a cynical, secular, closed-down culture, if I were a person who had very little interest in Christian faith, David and Phaedra would make me think again about the truth of the gospel by pointing me to music makers, artists, sculptors, and painters,” says Jeremy Begbie, the Thomas A. Langford Research Professor of Theology at Duke Divinity School, who supervised David’s doctoral dissertation. “They would make me wonder: Is there more to the world than there seems on the surface? Both of them are expanding our imaginations beyond the purely secular.”

Art is “stuff that Jesus is resurrecting,” said David in his Austin lecture, “and stuff that helps us behold the glory of God.” The juxtaposition of “stuff” and “glory,” earthy and divine, is quintessential David Taylor. And if the Taylors’ influence continues, maybe it will describe the church’s worship in the next generation, as well as its witness.

Andrea Palpant Dilley is the author of Faith and Other Flat Tires and a contributing editor at CT.