In this series

Chinese culture, which is influenced by Taoism and Buddhism, has deep roots in fatalism. Chinese people generally believe in the heavenly predestination of one’s life from birth. Parents are often concerned about when a baby will be born into the world as the date and time are auspiciously determinative of the baby’s future well-being.

They also believe in three interconnected issues related to fatalism, ranging from the most influential to the least: fate, luck, and feng shui. A popular proverb is yi ming, er yun, san fung shui (“fate first, luck second, and feng shui third”). The Chinese traditional belief is that our destiny is 70 percent predetermined by luck and that we can make changes to destiny only to the remaining 30 percent. If a person’s luck is “bad,” feng shui is said to be able to improve his or her situation.

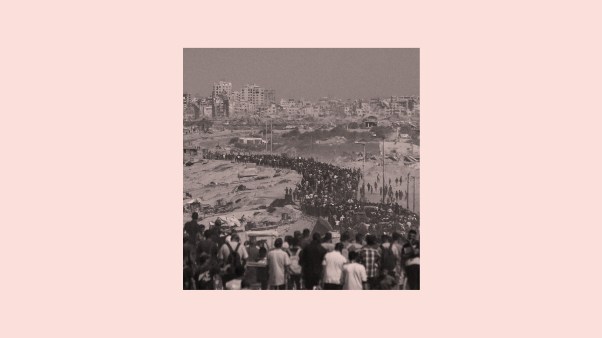

Hong Kong faced unprecedented social unrest in 2019, which was further impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The former led to the enactment of the national security law (NSL), and the latter led to an exodus of foreigners due to the government’s overly stringent lockdown policy. Many superstitious businesspeople believed that Hong Kong would face a pivotal moment in its long-lasting prosperity, based on a foretelling from the Purple Star Astrology (紫微斗數), one of the ancient classic writings on fatalism.

Christians’ interpretations and responses to fatalism and events in the last four years have been somewhat polarized. Conservative Christians choose to accept the situation as predestined by God and often base their response on Romans 13. They choose to adjust themselves to the new normal under the NSL, since the government regime is supposed to be ordained by God. On the other end of the spectrum, more progressive Christians were awakened to the saying that God demands compassion and justice. They sympathize with the social movement and base their actions on Micah 6, which talks about speaking up for the oppressed. To them, the suffering Christ is manifested in social unrest, and civil disobedience is considered a righteous act in the name of Christ.

Churches have become highly divisive since then. Certain megachurches have experienced a 30–50 percent reduction in attendance. Questioning what God is doing in Hong Kong, many have chosen to emigrate, stop going to an institutional church, or form new Christian communities.

Recently, church leaders and seminary scholars have started to offer theological explanations of what has been happening in Hong Kong in the last few years and to suggest new ecclesiological frameworks as we advance. One outstanding explanation is that the suffering Christ has manifested in Hong Kong. Like our counterparts in China, God has cast the Christian community out of complacency into suffering so that we would stop trusting our economic prosperity and lean closer to God. God is chastising the church to facilitate its sanctification, and the church may undergo a period of persecution and suffering that it has not experienced in the last 50 years.

There are more discussions about the need to model faithful witness for our counterparts in mainland China amid an unfavorable environment for religions. Certain actions are even gaining momentum. For instance, local churches under particular major denominations must incorporate independently to lessen any impacts on the denomination if challenges from the authorities arise. Others are experimenting with decentralized leadership and pastoring by organizing house-church-style Sunday worship services. There is also the “microchurch” experiment, in which young people are empowered by the church to lead among themselves and even to administer Holy Communion, but not baptism.

While it is a biblical truth that God has an overarching plan for humankind and has determined what the appointed time for everything is, I believe God has also allowed us to partake in the management of the earth and to take responsibility for our decisions in life. We should provide a balanced and comprehensive teaching of the biblical truth. Internally, we have to teach believers based on the Word of God on the subjects of predetermination, free will, and their consequences, as well as how the two ideas are not mutually exclusive. Externally, believers should be equipped to answer the popular belief of fatalism in various schools of thought and to demystify their sources of authority. Fatalism often implicitly requires a concept of work-based salvation, but Christians must share with unbelievers salvation by grace through faith in Christ.

Read our contributors’ bios in the series’ lead article, Destiny Is All? How Fatalism Affects Churches Across Asia. (Other articles in this special series are listed to the right on desktop or below on mobile.)