As a complement to our coverage of "The Ten Most Influential Christians of the Twentieth Century," historian Bruce Shelley highlighted a few of the most controversial Christians of the century. One of his selections is the famous fundamentalist William Jennings Bryan, whose story is a perfect example of winning the battle while losing the war. —Elesha Coffman

Bryan made his last impression on public opinion from a sweltering courtroom in Dayton, Tennessee, in 1925. He served as an associate prosecutor of the young schoolteacher John Scopes, who had taught the theory of evolution to his pupils in defiance of a six-month-old state law prohibiting the teaching of "any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible." The ACLU had manipulated Scopes' arrest and obtained agnostic Clarence Darrow as the chief defense attorney, thereby setting the stage for the dramatic “monkey trial.”

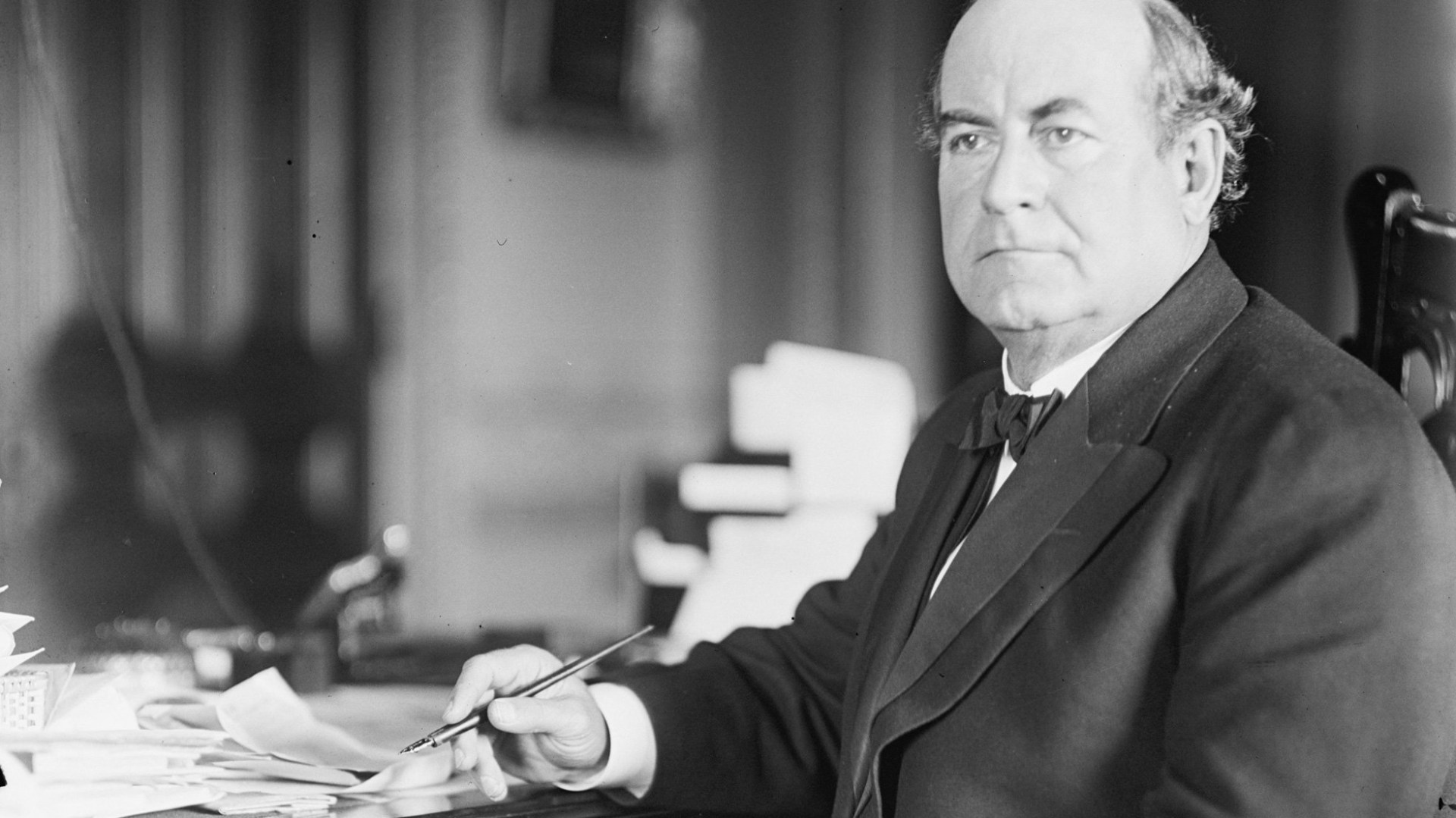

At the time many Americans considered Bryan a heroic figure standing for the nobility of the common man. He was, after all, raised in southern Illinois on pork, potatoes, and McGuffey Readers. Not only had he entered the U.S. House of Representatives at age 31, he had also received the presidential nomination of his Democratic party three times and served as Secretary of State under Woodrow Wilson. He seemed like the obvious choice to lead the campaign against evolution, even though he had not practiced law in 30 years.

Unfortunately, in the red-brick courthouse in Dayton, Bryan fell into the twentieth-century cultural chasm between the traditional values of Bryan's small-town America and the "modern" values of urban America.

The trial turned into a media circus, the first event broadcast live on radio coast to coast. Even worse, the famous cynical journalist H.L. Mencken gave blow-by-blow reports in his newspaper columns, fixing Bryan's name in the public mind as the bigoted Bible Belt fundamentalist.

Nonethelsss, "The Great Commoner," as many called Bryan, won the case. Scopes was found guilty and fined $100. But the humiliating cross-examination Bryan suffered when Darrow put him on the stand painted the prosecutor as a simpleminded rube (for example, when Darrow pressed him to speculate on the date of Noah's flood, Bryan snapped, "I do not think about things I don't think about"). Less than a week after the trial, Bryan died in his sleep.

Because both sides had agreed to end proceedings early (Darrow, knowing he had lost, recommended a guilty verdict to save time), Bryan never delivered his final summation for the trial. But two days after his death, his wife released his prepared remarks, which read: "Science is a magnificent material force, but it is not a teacher of morals. … It can build gigantic intellectual ships, but it constructs no moral rudders for the control of storm-tossed human vessels. … The world needs a savior more than ever did before."

Mencken, however, got the last word. His anti-eulogy attacked Bryan, saying it was appropriate he spent his last days in a "one-horse Tennessee village" because he loved all country people, including the "gaping primates of the upland valleys," and delighted in "greasy victuals of the farmhouse kitchen." What moved Bryan, said Mencken, "was simply hatred of the city men who laughed at him so long." He had "lived too long, and descended too deeply into the mud, to be taken seriously hereafter as a fully literate man."

* For more, see issue 55: The Monkey Trial & the Rise of Fundamentalism

Elesha can be reached at cheditor@ChristianityToday.com.

Copyright © 2000 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.