“Why have we reached such a height of madness as to forget that we are members of one another?”

The pastor was frustrated with conflict rippling through the congregation.

Clement asked this pointed question of the church of Corinth in the year A.D. 96. Drawing upon Romans 12:5, he challenged its tendency to tear to pieces the members of Christ and raise up strife against our own body.”

It can be tempting to idealize the early church. In passages like Acts 2:42–47, a vibrant and unified community seems to be the epitome of church health. But only a few chapters later, money, deception, and ego disrupt their life together. Conflict, dysfunction, and unhealthy behaviors have been a normal part of church life from the very beginning.

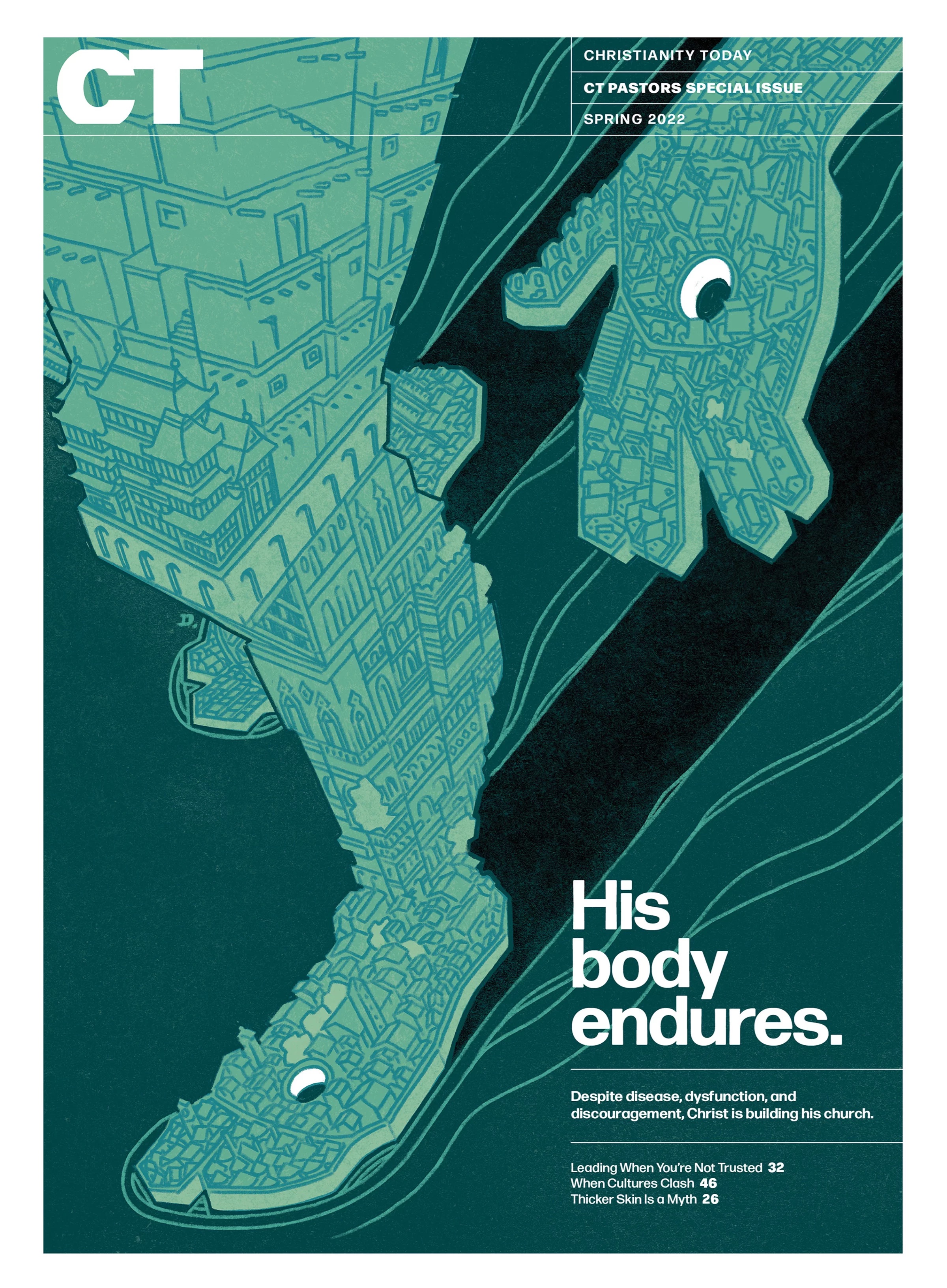

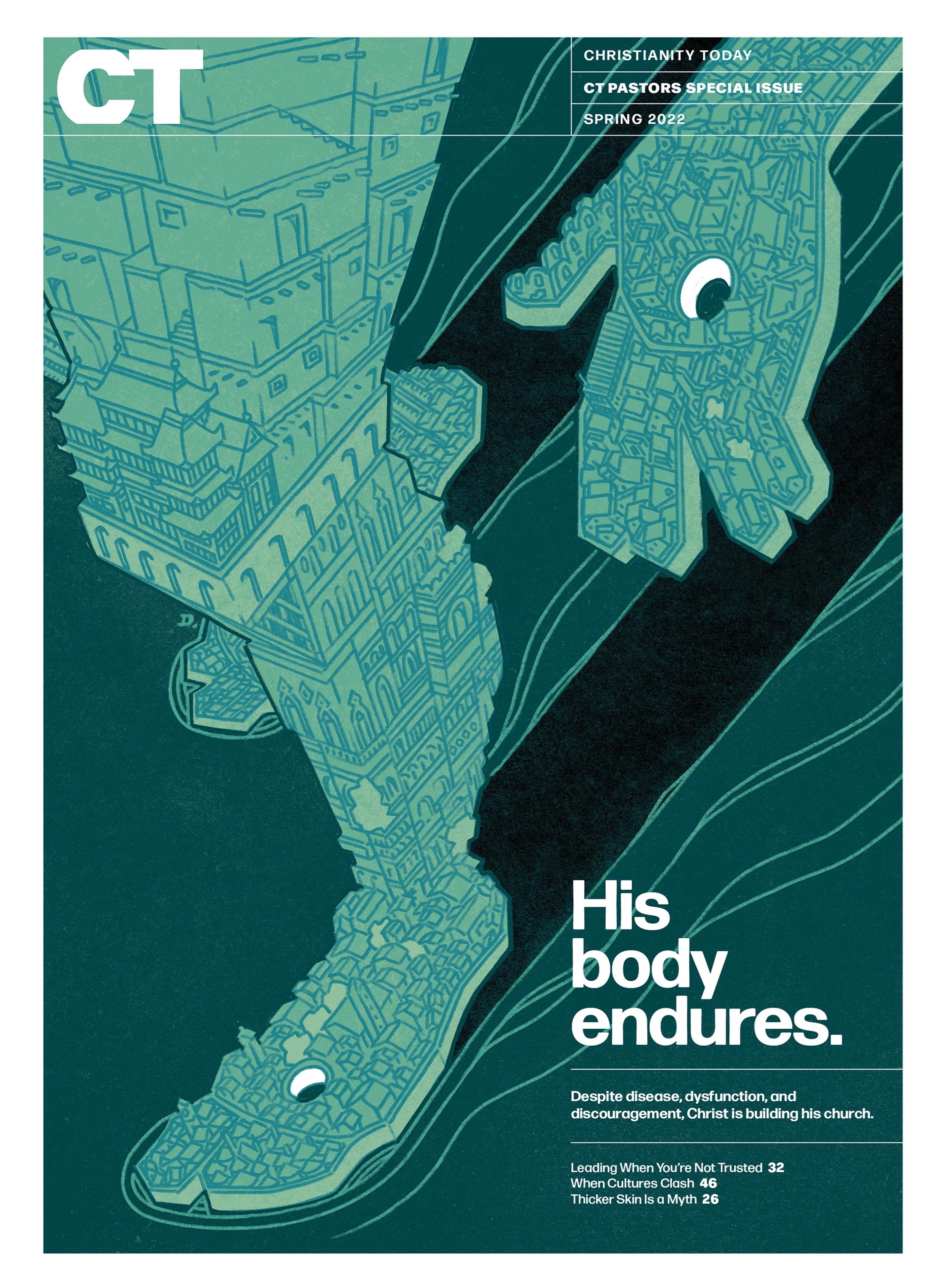

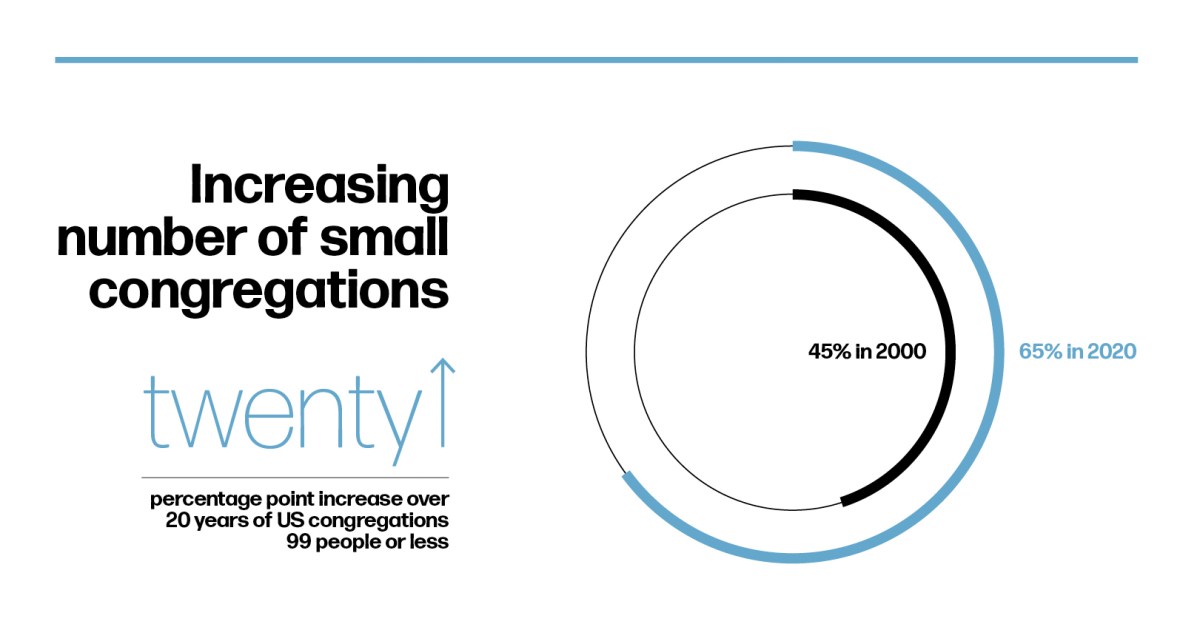

This CT Pastors issue invites us to think afresh about church health. We explore how pastors can assess the health of their congregations by looking beyond measures like numerical size or financial growth. We probe key issues for a pastor’s own health, like dealing with negative feedback or a congregation overstepping boundaries. And we look at ways to address specific issues within a church community, like racial tension and relational conflict.

As a lay leader, I’ve tended to think of church health by focusing on spiritual maturity—assuming that a healthy church is one made up of committed believers, deeply formed by prayer and Scripture, who actively serve their community and reflect the fruit of the Spirit.

But the pastor of our small mission church has given me a different perspective: A truly healthy congregation is one that’s made up of people at all different points of the journey of faith. Alongside mature disciples, there are immature Christians, people with all sorts of serious problems, and non-Christians too. This is what a church that embraces the Great Commission looks like. So if you’re pastoring a congregation with some dysfunctional, conflict-prone, or ego-driven people, good work!

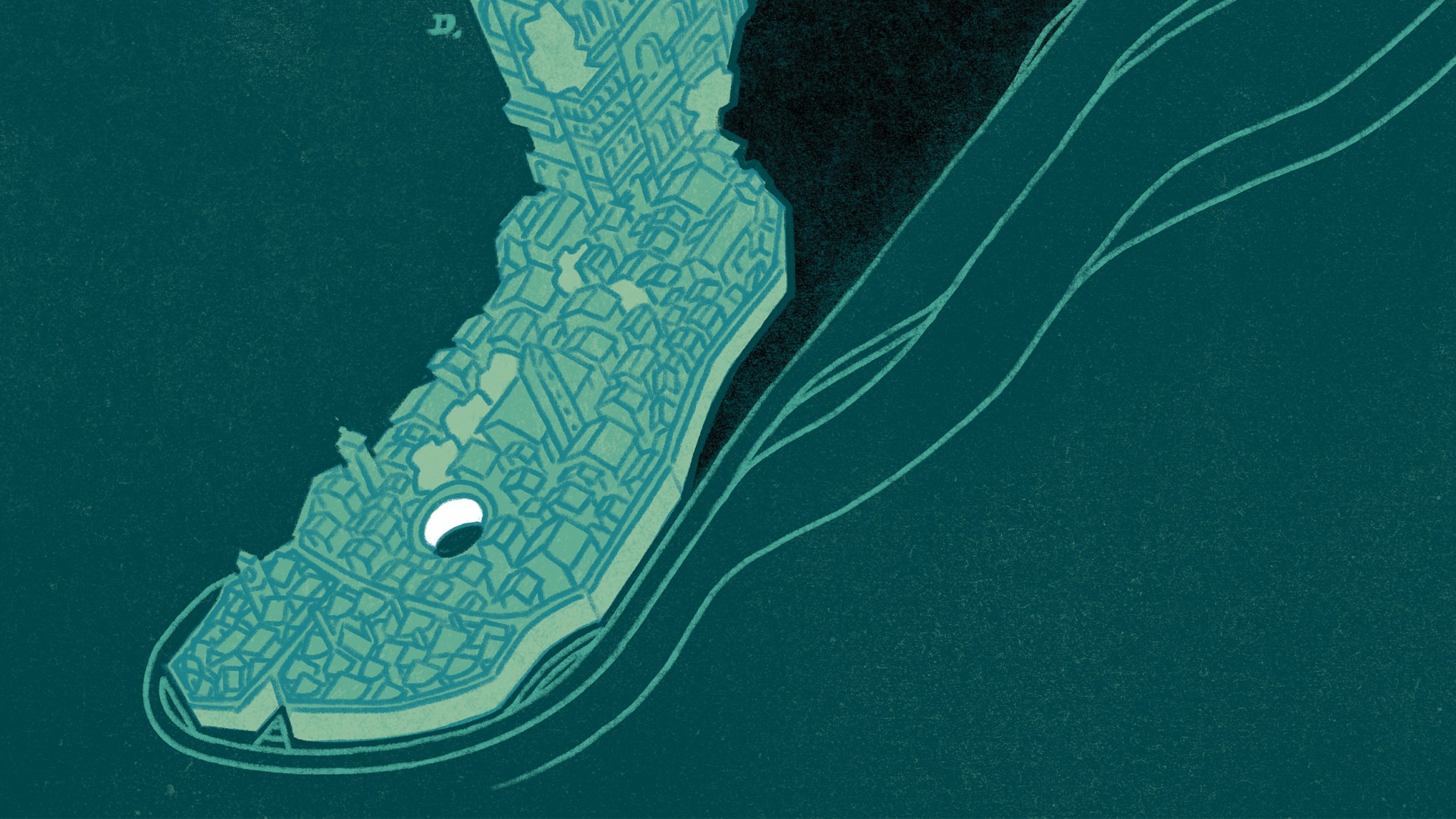

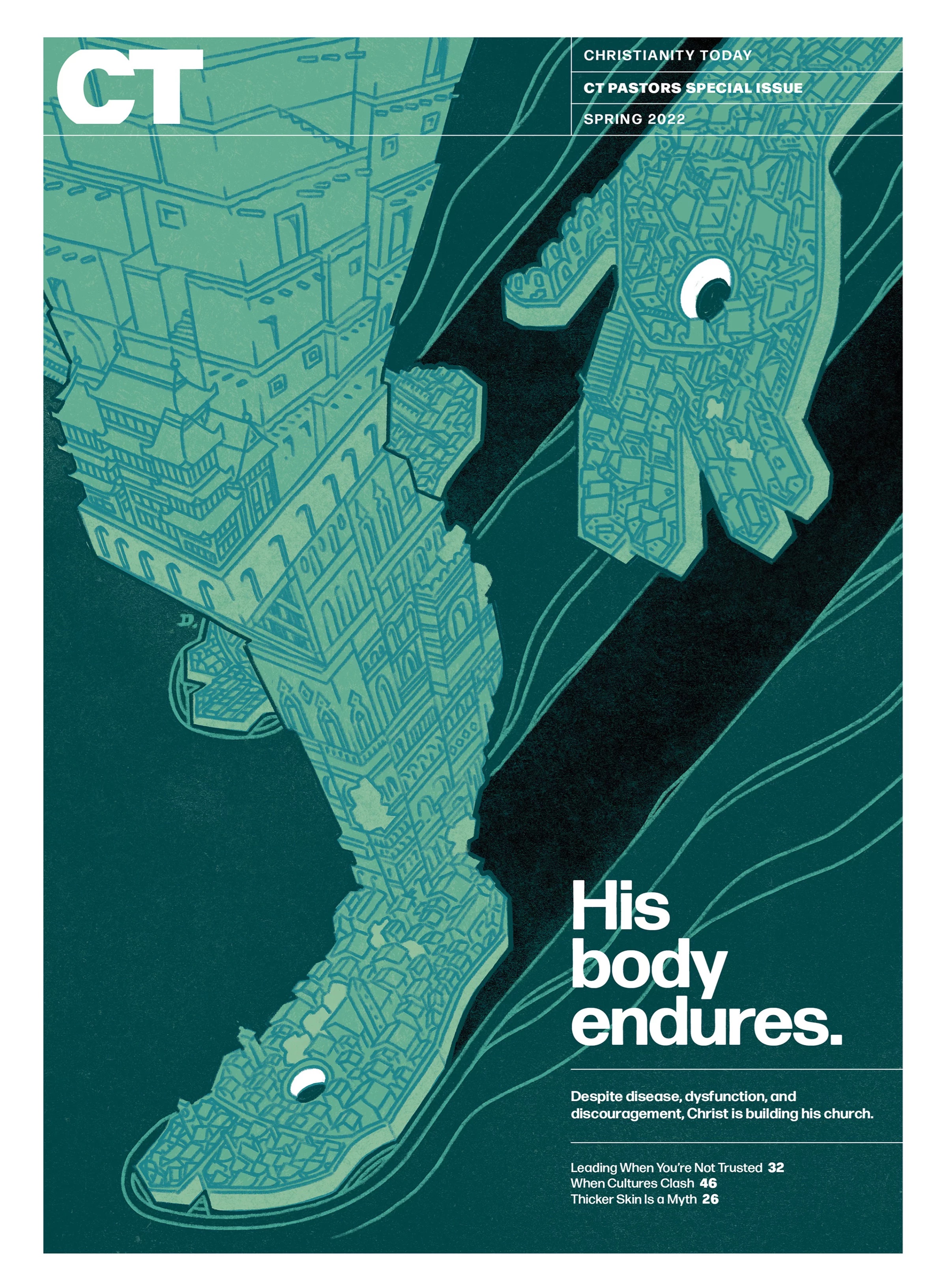

Over the past few years, “church health” hasn’t just been a metaphor. The toll on our bodies and spirits is real. But despite the heavy burden, his body endures. We can trust the work of the Spirit, through whom the church “will grow to become in every respect the mature body of him who is the head, that is, Christ. From him the whole body, joined and held together by every supporting ligament, grows and builds itself up in love” (Eph. 4:15–16).

Kelli B. Trujillo is CT’s projects editor.

This article is part of our spring CT Pastors issue exploring church health. You can find the full issue here.