Chip Asberry removed his socks and shoes and rolled up his jeans before he stepped out of the van. The 15-year-old looked over his shoulder just as the wave hit.

He saw it take one person, then another, then he was under water. The current, moving at 60 miles per hour, rendered swimming impossible, and Asberry struggled to keep his head above the water.

“I was just trying not to drown and grabbing onto whatever I could,” he said. Eventually he grabbed a limb and used it to pull himself up into a tree. He lost his glasses in the river, clouding his comprehension of the chaos. God, just let me out of this and I’ll do whatever you want me to do, no matter what it is, Asberry bargained from his perch 40 feet in the air.

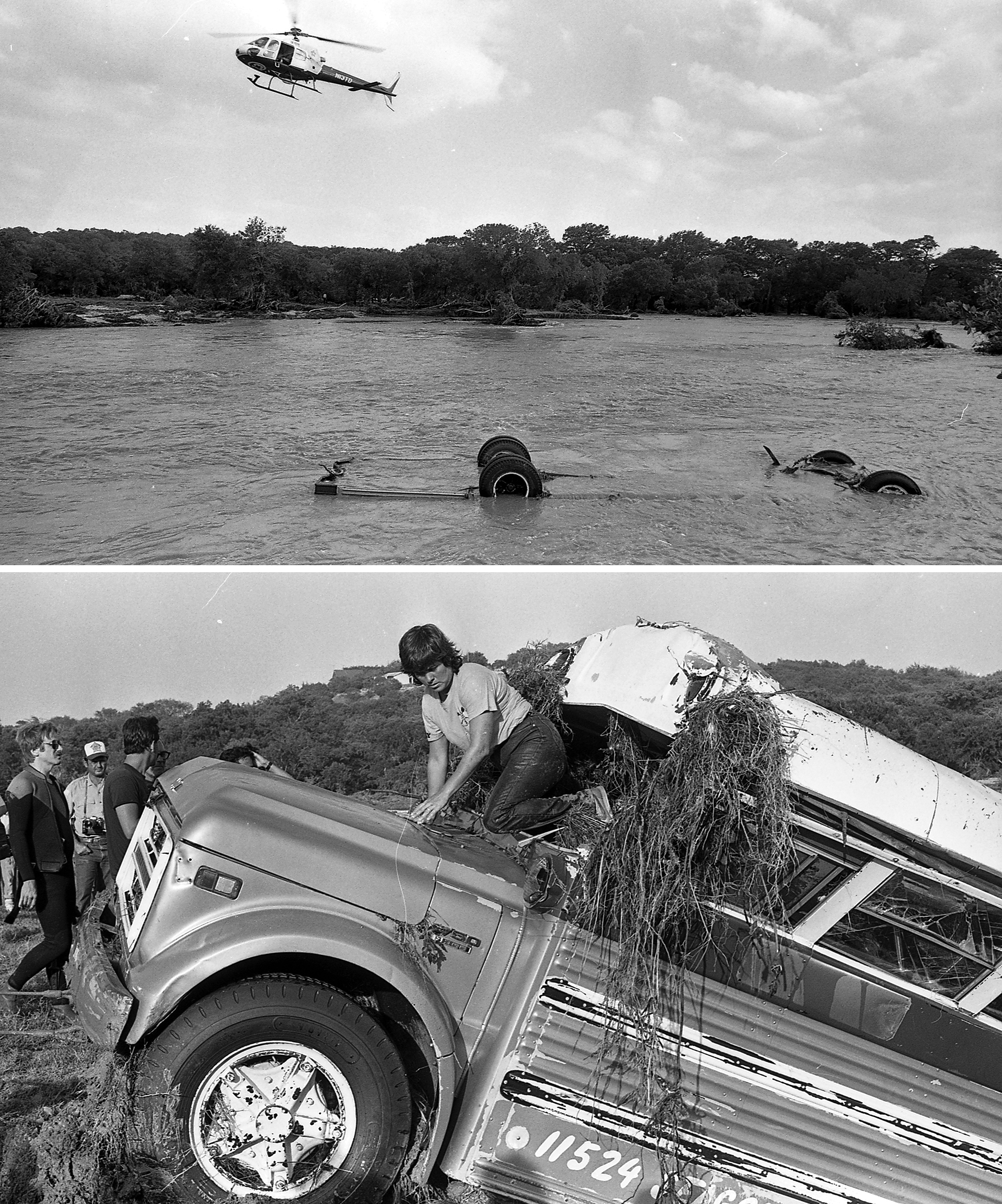

San Antonio Express-News via ZUMA Wire

San Antonio Express-News via ZUMA WireGene Marsh, 14, dug his fingernails into the bark of a different tree and pulled himself up. He broke two ribs in the scramble, but adrenaline overpowered the throbbing pain in his torso. An 11-year-old girl rushed toward him in the water. She had blacked out when the wave hit, and her next memory was Marsh pulling her into the branches, the two of them inching higher up the tree as it shook and swayed amid the current.

“She just kept asking if we were going to go home, and all I could tell her was ‘yeah,’ ” Marsh said, certain they wouldn’t make it out alive. “I couldn’t tell her what I was really thinking.” He heard helicopters circling above, but the current wasn’t slowing.

If anything, it was rising.

In the pre-dawn light of July 17, 1987, nearly 40 kids struggled in the Guadalupe River as it overflowed its banks in Comfort, Texas, 50 miles northwest of San Antonio. They had woken early on their last day of Bible camp and skipped breakfast to get ahead of the looming flood, but they were too late.

Now the trees lining the banks were their only lifeline.

Tara Chatham could hear people yelling, “Head to the trees and hold on!” The 14-year-old made it to one with several people already in it. A group of boys took off their jeans and tied them together into a rope, lowering it to the kids in the water. Chatham tried to grab it but slipped. She went underwater and resurfaced, just once, before she disappeared again.

It would take days to recover the bodies of ten children who perished in the flash flood that morning, one of the deadliest natural disasters in the region of Texas known as the Hill Country. Its anniversary would be commemorated by journalists, with a humble memorial plaque, and in a speech by President George H. W. Bush.

For those left behind when the water receded, the struggle was only beginning. Dreams derailed. Best friends drowned. A sweetheart buried in debris.

There may be no starker image of bad things happening to good people than children giving a week of summer vacation to worship God and study Scripture only to be swallowed up by floodwaters.

All the usual questions about God and evil would ensue. And for surviving campers Asberry, Marsh, and Chatham, one question in particular would linger over time: When the body survives, what determines if faith will?

Trevor Paulhaus

Trevor PaulhausThe term theodicy first popped up in the early 18th century. But plenty of scholars would say humans—at least those who belong to Abrahamic faiths—have been attempting to square the existence of an all-powerful, loving God with the existence of suffering since Genesis, where Cain first shakes his fist at the heavens.

The Bible offers its earliest take on “modern” theodicy, as we might think of it today, at least six centuries before Christ, when most scholars think the Book of Job was penned.

The 12 disciples grappled aloud with the problem of suffering. In response, Jesus mentioned a local tower that had collapsed atop 18 people and asked his disciples, rhetorically, if they thought victims died because they were especially vile sinners.

Perhaps missing the irony, Pat Robertson offered that explanation on television following the September 11 attacks in 2001, cataloging the various sins embodied by New York City.

There may be no starker image of bad things happening to good people than children giving a week of summer vacation to worship God and study Scripture only to be swallowed up by floodwaters.

The scholarly field of theodicy is vast and imaginative. There are theories that God allows suffering to make us better people. That he allows evil so we can see just how good his blessings really are. That injustice is required as some sort of variable to balance a great mathematical equation that, somehow, atones for all the sin we’ve let into the world.

There will be no debating theory here.

As the theologian David Bentley Hart wrote after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that claimed more than 230,000 lives: “Nothing that occurred that day or in the days that followed told us anything about the nature of finite existence of which we were not already entirely aware.”

Humans, as a group, have always known tragedy. This is a story about how we come to terms with it on our own, as individuals.

The notion that a good God wouldn’t allow suffering has been a growing obstacle to Christian belief for at least four generations—as long as pollsters have examined such things. While only 18 percent of non-Christian baby boomers cite the conundrum as reason for their nonbelief, the Barna Group found that nearly a third of today’s non-Christian youth do. The same goes for millennials.

Among Gen X, the generation to which most of the Comfort flood victims belong, more than 1 in 5 non-Christians say they can’t reconcile the presence of evil with the idea of a loving God.

But no one is born with their hands washed of the God-versus-evil paradox. There is a journey leading to every belief, and the role that suffering plays in that journey—the effect that suffering has on our faith—has only recently become the subject of much study.

On the last night of camp at Pot O’ Gold Ranch, a family-run Christian youth camp in Comfort, pastor Rene Freret felt God urging him to deliver a stern message to the kids in attendance: Get right with God before it’s too late.

He had awoken that morning with a heavy heart. During a week of preaching at the camp, he had noticed bitterness and backbiting among the kids there. “They were just not getting along and fussing,” he said. He took their behavior as a sign they were distant from God.

“Sometimes rebellion comes out because a person hasn’t come to know the Lord,” he said. He stayed in his room all day praying, reading his Bible, and preparing for that night’s sermon.

“Young people,” he said at the close of his message in the heat of the camp’s open-air tabernacle, “if you’ve got a rebellious spirit about you, you need to deal with that because this may be your last chance. You may not see your parents or preacher again. If you’re not right with God, you need to examine your heart and make sure you are.”

It started raining after the campers went to bed that night.

Just after 3 a.m. on the morning of the flood, officials from the local fire department called the camp’s operators to warn them that the Guadalupe River, which runs parallel to the camp’s entrance, was expected to rise. More than 12 inches of rain had recently fallen across the Hill Country, and low-lying areas were already underwater. The river had left its banks before but had never flooded the camp’s facilities, which were more than half a mile up the road.

At the time, the camp’s emergency protocol advised against leaving the camp “during serious floods” but also noted: “There has been no flooding of any of our camp facilities since we are built on high ground.”

It was a Friday, the last day of camp for the 400 kids at Pot O’ Gold. They had paid $65 each to spend five days and four nights away from home, some for the first time ever. Campers stuck to a strict schedule that was heavy on Bible study. They hiked up to the tabernacle twice a day under the scorching July sun. Each afternoon they got three hours of recreation time when they could ride horses, play sports, or go swimming—one pool for boys and another for girls.

The campers were scheduled to leave after breakfast that morning, but the camp operators woke the chaperones early to warn them about the potential flood risk. Breakfast was packed to go as the kids were hastily awoken and corralled into some buses and a van.

Just one road led in and out of the camp, and it passed beside the river. So before the campers could distance themselves from the rising water, they had to face it head on. The caravan drove half a mile north on Pot O’ Gold Road until it forked, less than 200 feet from the river’s edge.

The camp was warned not to let the vehicles go right at the fork, which would lead them over Hermann Sons Crossing, a low-lying bridge that crosses the Guadalupe. Instead, they turned left, driving away from the bridge.

By the time the campers pulled out, the river had already left its banks, spilling several inches of water onto the road near the camp’s entrance. Richard Koons, the youth pastor at Seagoville Road Baptist Church in North Texas, drove the last bus in the caravan. Chatham was on it. Following Koons was a smaller van carrying the remaining campers from his church, including Marsh and Asberry.

Koons would say, decades later, that he believed strongly in God’s sovereignty. “God is in control of everything,” he said. “Our bus actually moved two times in that line. We were actually close to the front, and then because of some circumstances our bus got moved back to the next-to-last bus in line with our van.”

The vehicles in front of him drove through the water without issue, but as Koons turned the steering wheel to the left to make the turn, his bus stalled. “All I could think was, man if I don’t get this bus started I’m going to be in trouble when I get back to Dallas because somebody’s going to have to come get us,” he said. He didn’t sense danger until he looked in his rearview mirror and saw the van behind him was already halfway under water.

He spotted a big tree surrounded by dry land just across the flooded street. He made a quick decision to get the kids get off the bus and have them join hands. “I told them to walk over to the tree and we’ll figure it out,” Koons said.

Many of the campers managed to reach the tree, but by that time the river had expanded and the water was rising quickly. What was dry land seconds before suddenly disappeared under the fast-moving current. The kids tried to climb the tree, but there wasn’t room for all of them. Some fell and others, like Koons, just let go.

“I thought I could swim down to the next tree and that’s when I realized how fast the water was traveling,” Koons said. He managed to grab a limb further downstream and pulled himself into a tree to which several campers were already clinging. He tried to count the kids he could see and quickly came up short.

If, as Koons believes, “God is in control of everything,” then perplexing questions arise: Did God pull Tara Chatham down under the water? Did he pluck her out again?

After falling back into the river, Chatham woke up in a different tree all alone with no memory of how she got there or how much time had passed. As she clung to the tree, she wondered what happened to her brother, Scott, and her friends, and if anyone would ever find her. After what felt like hours, she waved her arms to get the attention of a helicopter passing overhead and a rope was lowered from its belly.

She reached for it but slipped again and fell into the raging river.

As she was pulled downstream, the helicopter dropped close to the water and a rescuer with the Texas Department of Public Safety climbed out onto the skid. “He grabbed the hair on my head and then the back of my shorts and just yanked me in the helicopter,” Chatham said.

While the rest of the morning is a blur, she remembers every second of the rescue. “I can still see him today and smell his smell and everything,” she said. “It was just such a relief, like He saved me. He’s got me now.” He wrapped her in a blanket and held her. Then everything faded to black.

Decades later, Chatham recalls that her ex-husband once called her invincible. But she doesn’t feel that way. Time and again, she’s found herself pleading with God for answers and peace.

“Why us, why our group, why those kids?” she demanded after the accident. Hadn’t they been doing everything right? Hadn’t they been praising God 12 hours before he let the river take them? Why, if he were in control of everything, would he allow this to happen to his children?

Questions like these are at the heart of the God-versus-evil paradox. They populate news stories and Sunday sermons in the wake of every major natural disaster. It turns out, however, that they’re not just academic. They may also be at the root of the psyche’s ability to process and heal after trauma.

Theodicy is not simply “an intellectual exercise,” Abilene Christian University psychologist Richard Beck concluded in a 2008 study. “Theodicy properly understood is an experiential burden. The individual believer must reconcile his or her life circumstance with fundamental beliefs about God.”

Jamie Aten, a psychologist at Wheaton College, would know: His family moved to Mississippi just days before Hurricane Katrina made landfall and ravaged his community. He also survived colon cancer.

“Oftentimes when we go through a trauma, it disrupts our ability to make meaning,” said Aten, who now studies the relationship between natural disasters, faith, and mental health.

“Most of us operate from what some researchers call a ‘just world theory,’ the idea of ‘I’m a good person so good things should happen.’ But then when bad things happen to us, it really can kind of rock the way we understand the world and even the way we view God.”

Research has shown that how a person views God before experiencing suffering plays a big role in determining how they’ll react afterward. Aten illustrates: Say that two Christians who have the same job and attend the same church every week both lose their homes in a natural disaster. The one with a more loving view of God may come away feeling that God protected him and spared his life, while the other, who views God as more wrathful, might feel God is punishing him.

Trevor Paulhaus

Trevor PaulhausThe just world theory was likely entrenched—consciously or not—among many families at Balch Springs Christian Academy, a school run by Seagoville Road Baptist Church where most of the children on the trip were students.

Today, the small church is a dated red-brick building with a white steeple that appears little changed from 30 years ago. Just to the right of its bright blue and yellow gym hangs a memorial for the 10 lost in the flood, two rows of black and white pictures framed above some filing cabinets, obscured by old basketball trophies.

When Chatham and the other surviving kids returned to school in the fall after the accident, parents and teachers were in a hurry to regain a sense of normalcy. The tragedy hung over the campus but wasn’t talked about. Harder still, she overheard some of the parents make disparaging remarks like, “Why did all of the good kids have to die?”

In social-psychologist speak, comments like those fit into what’s called the “shattered assumptions theory.” Children raised in stable homes with pleasant upbringings are likely to build quiet assumptions that the world is benevolent, that things make sense, and that suffering tends to happen to other people but not to them. “Bad kids” may someday get what’s coming to them, but the good kids will pass through the fire unsinged.

Having those assumptions shattered may well trigger symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and questions about the nature, or even the existence, of God.

Chatham thought of herself as one of the bad kids, even before the accident. Her dad used alcohol to get through tough times, and she learned to do the same in her teen years. Her dad’s addictions drove her parents to separate, her mom cleaned after hours to help pay the tuition at Balch Springs, and her brother was diagnosed with leukemia.

“My mom pretty much made us go to church and be surrounded by the church people,” Chatham said. “But as far as trying to deal with some of the hard things, I chose to run to other things like drugs and alcohol to kind of numb the things that I was going through.”

Her brother, Scott, also survived the accident. He had just finished chemotherapy and still had a catheter in his chest from the treatment. His mom was nervous about letting him go to camp, but his doctor said it would be fine—as long as he didn’t go swimming, which could cause an infection.

The doctor’s words ran through Scott’s mind that morning as he stepped into the rising river. In a video of his rescue replayed years later, Scott looks strong, even after the chemo. He is shirtless, the rushing water lapping at his white sneakers as he balances on a tree branch.

Chatham often dwells on her brother’s strength when she remembers him, but she says Scott was easily frustrated by his limitations with cancer. He wasn’t always the best patient and could be inconsistent when taking his medications.

“He kind of thought he was invincible,” she said.

He died when he was 19, three years after surviving the accident. Chatham and her father, who were mostly estranged by that point, were together in the room during his final moments. “Scott put our hands together like, ‘This is what I want y’all to do,’ ” Chatham said. “He always wanted the family back together.”

If trauma shatters our assumptions of a safe world, Chatham’s experience ground hers to dust. She spent much of her adult life in a near-constant state of fear and anxiety. When she had children of her own, she spent the first several years of their lives praying she wouldn’t live to see their deaths. She homeschooled them, went to summer camps with them, and kept them close.

“My son, he had sleep apnea when he was a baby, so a couple of days after he got home he stopped breathing and he had to be on a monitor—talk about fear,” Chatham said. “I just prayed for years, like I can’t really live like this anymore. . . . Probably over the last 10 years or so God really brought me through that fearful period and said, ‘I can handle it. Let me deal with it.’ ”

Chatham made amends with her father years after her brother willed it. Her father got to know her children, and they never saw him take a drink. Toward the end of his life, he developed pulmonary hypertension and cirrhosis of the liver, which made it feel like he was drowning. Chatham helped her mother care for him, and together they placed him in hospice care and began preparing themselves for his death.

Then, overwhelmed by the pain of his disease, her father shot and killed himself before nature could run its course. Her mother found his body.

“Here we are thinking my dad’s going to die on hospice and we’re going to be surrounding him and loving him through it and then all the sudden . . . you’re in shock, thinking this is not the way it’s supposed to be,” Chatham said. “I thought there was no way we can get through this.”

But for Chatham, the God who threw trials her way also delivered her from them.

“When you’re in the midst of that, you don’t feel very strong, even though you’re getting through it and stuff, but I know for a fact that whatever I go through now that he’s going to be with me.”

This notion that “God is suffering alongside me” is a textbook picture of what theologians call a benevolent theodicy, one that suggests God somehow uses suffering for our good or is at least compassionate in the midst of it. So is the Pauline teaching that suffering produces character and hope (Rom. 5:3–4).

These benevolent theodicies are important. Researchers like Aten think such beliefs can actually protect against PTSD in the aftermath of trauma. They might also protect faith itself.

But according to Shelly Rambo, an associate professor at Boston University School of Theology, there’s more than one right way to process trauma.

“Sometimes people think it’s either you keep your faith or you lose your faith,” said Rambo, who focuses on the relationship between religion and trauma. “And what’s more true is some people say, ‘I can no longer hold a certain version of God.’ That view of God can no longer be sustained given the experience that happens to you, and so you need to abandon that and find solace and strength elsewhere.”

Trauma might cause people to stop believing that God controls everything that happens in the world and, instead, they might begin defining God more by his solidarity with their suffering.

“People can explain that through understanding Jesus’ death on the cross,” she said. “God experiences suffering and knows that suffering, so there’s no place of violence, loss, or suffering that God doesn’t know.”

There are less benevolent theodicies, of course—those that render God as neither all-powerful nor all-present.

But even those who find comfort in such views, according to Rambo, might not jettison belief in the divine outright. They may come to believe in a diminished God and still find themselves drawn to some sort of spiritual community.

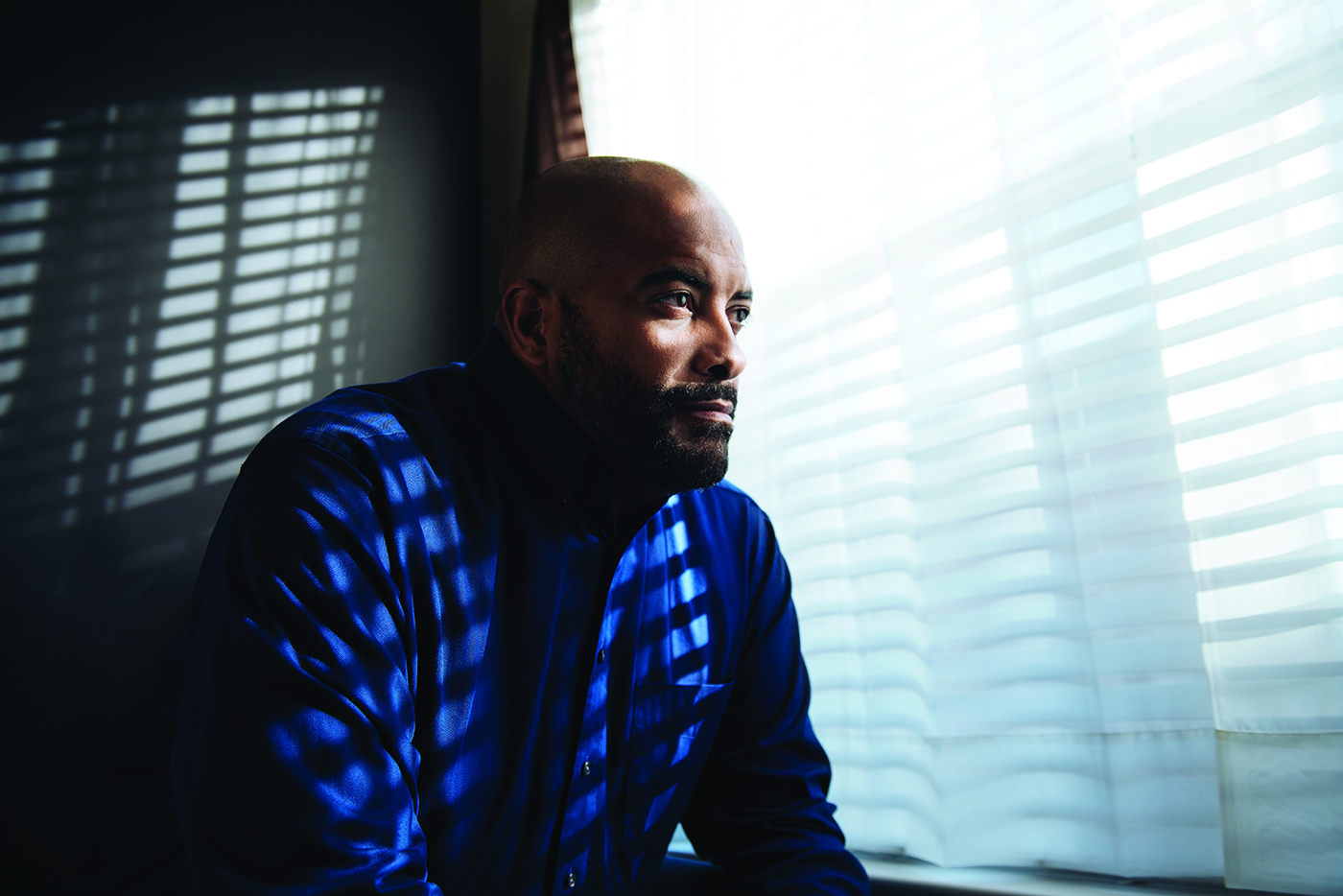

That’s where Gene Marsh found himself, decades after he was rescued from the flood and had walked away from the faith of his childhood camp days.

Marsh worked for months to save enough money for camp that summer. His girlfriend’s fiercely overprotective mother was letting her go for the first time, and he wasn’t about to get left behind. They were both 14 and had already been a couple for a few years.

“Back then I wouldn’t even call it dating. It was just like you were girlfriend-boyfriend,” Marsh said. “We weren’t driving yet.” They saw each other at school and on school outings. She was a cheerleader and he was on the football team.

The days after the accident are fuzzy. Marsh remembers being rescued and taken to the hospital, the bandages around his chest, his parents driving nearly five hours from Balch Springs to pick him up. But he doesn’t remember who told him that his girlfriend, Leslie Gossett, didn’t survive.

Gossett’s family was one of several that sued Pot O’ Gold camp for negligence following the accident, alleging that the camp—which declined to comment for this story—failed to heed warnings and was reckless with the children’s safety.

Their suit argued that the young girl “in all reasonable probability suffered immense and indescribable pain, suffering, and mental anguish in the moments prior to her death.”

In response, lawyers for the camp argued that negligence didn’t lead to the accident, “as it was caused by an ‘act of God’ as that term is defined in the law.”

“I lost all faith in everything” after the accident, Marsh said. “What kind of God sends kids out and kills them?”

The following school year was the “most terrible” he’s ever experienced. He no longer felt welcome at Balch Springs Christian Academy. Other students and parents made him feel almost guilty for surviving when others did not.

Similar to many conservative private Christian schools, Balch Springs promises to protect children and teach them to walk with God. According to the current student handbook, children are given detention for holding hands or hugging, the same punishment given for cheating on a homework assignment.

Marsh transferred to a public school midway through the year.

“I don’t fit in with your Christians, basically,” Marsh said. “I ask too many questions about the whole belief. Too many open-ended questions.” He would like to think there is a higher power, but he doesn’t want his faith to be defined by what he sees in Christianity.

Today, he wears his gray, wiry beard long, just off of his chin, and he’s covered in tattoos he calls his “road maps.” His right arm has 11 skulls on it, one for each of the ten lost that day and one for Chatham’s brother, Scott.

Marsh’s hours driving a tow truck are long and unpredictable. A night may crawl with downtime or race with back-to-back service calls. His wife, Debbie, rides along and occasionally asks if Gene’s sick of her yet. He answers honestly, “Nope.”

Debbie sat quietly in the passenger seat as Marsh talked about the flood, his faith, and his PTSD symptoms. His tone shifted when he mentioned Gossett, his girlfriend who died. He paused, then climbed out of the truck and closed the door.

“My life would probably be a whole lot different if it wouldn’t have happened because the woman sitting next to me right now would’ve been Leslie,” Marsh said, tears in his voice.

Of course, it’s no secret to his wife, and she’s understanding.

“I know I was young. And they say young people don’t really know what love is,” he said. “But there was something different about her, that I know I was going to be with her for the rest of my life. And it just didn’t happen. It was taken away from me.”

Over chips and queso at Cafe Del Rio in Mesquite, Texas, the couple made plans to attend “church” that evening, which is what they call a gathering of their motorcycle club.

“Sometimes they’re better than family,” Marsh said.

Trevor Paulhaus

Trevor PaulhausReturn for a moment to the just world theory, the idea that good things happen to good people. The flip side—that bad things happen to bad people—is what Jesus cautioned his disciples against embracing too eagerly.

But for anyone after or in the midst of a trauma, it’s hard not to wonder: What if you’re suffering because you deserve it?

William Edgar, a professor of apologetics at Westminster Theological Seminary, gently reminds us of the basic Christian truth that goes back to the Garden of Eden: Humans are responsible for evil in the world. God gave Adam and Eve a choice, they disobeyed God, and they allowed sin to enter the world.

There are clear moments in the Bible when God inflicted wrath as a punishment for individual or collective sin, although they were rarely a mystery. Prophets or God himself typically declared when plagues or exile or military defeats were punitive.

But all that said, Edgar is quick to clarify, sin usually brings enough suffering of its own and God is not piling on extra.

“If you drink too much you might lose your liver, but most of the time there’s an indirect relationship,” he said. “Job’s friends were trying to convince him that God was a push-button God, and the reason he suffered was because he did something wrong. And Job just knew that he hadn’t. He was puzzled by why he had to suffer, and he was justified in the end. The suffering is rarely given an immediate cause.”

He says blaming a victim for his own suffering would be cruel and “bad theology.” He also thinks it’s cruel and incorrect to say God allows a person to suffer to teach them a lesson.

Incidentally, psychologists like Aten call this kind of victim blaming “negative religious coping,” which when coupled with trauma can push victims closer to experiencing PTSD.

Christians are not obligated “to assure others that some ultimate meaning or purpose resides in so much misery.” ~David Bentley Hart

“There’s a whole school of people who believe that evil and suffering are for the purpose of improvement because without it we wouldn’t grow,” Edgar said. “Where is God doing a betterment in the Holocaust? We just don’t have those answers. We do know for Christians that suffering is something that shapes our lives and therefore grows our hopes and sanctifies us.”

There’s Paul’s benevolent theodicy again, from Romans 5. He builds on it a few chapters later in verse 8:28, that message that works its way onto so many sympathy cards: “We know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him.”

Edgar likens it to an orchestra, where each instrument contributes.

“If you had to sit through a Beethoven symphony and only listen to the piccolo, it would be awful,” Edgar said. “But if you weave all of the instruments together, it makes a lovely concert. What Paul is saying is that’s true even of bad things. When God uses them, they actually work together—sometimes we see it, sometimes we don’t—for the good.”

And that, ultimately, may be the best explanation found in Scripture about suffering: that it tragically exists, that it holds no value of its own, and that we may never understand it.

“Meaning-making isn’t as simple, in most cases, as ‘here’s my question’ and then getting an answer,” said Aten, the cancer survivor. “I can remember asking, ‘Why is this happening to me?’ Is it genetics or something from the environment, or is it lifestyle? Was I just unlucky? Eventually I realized that there would have been no answer that would have really made me feel whole. You still have cancer at the end of the day.”

As theologian N. T. Wright argues in Evil and the Justice of God, Scripture seems far more concerned with what God is doing about suffering than with helping us better understand it. Since the Fall, God has been “putting the world to rights,” Wright is fond of saying, and one day through Jesus, he will make all things new.

It may be simplistic, sure. But what if it’s true? Christians are not obligated “to assure others that some ultimate meaning or purpose resides in so much misery,” the theologian Hart concluded after the 2004 tsunami. To be human is to wrestle with the problem of suffering, he said. But wrestling has its limits. For many, satisfactory answers simply may not exist, and demanding them may misplace the focus.

“Ours is, after all, a religion of salvation,” Hart wrote.

After the Comfort flood, Chip Asberry seemed to come to the same conclusion.

Hey, this is our opportunity to go tubing,” Asberry and his friends joked as they packed their bags and loaded the van the morning of the accident. “We didn’t know how serious it was, as kids,” he said. Reality caught up to them when the wave hit.

“I remember being scared,” Asberry said. “Angry was never really part of it, even afterward.” As a kid, he questioned why God would allow such a terrible thing to happen. Even years later, he can’t say for sure he could answer that question.

“I’m not so naive to say that I think God did this for a reason,” Asberry said. “But I do think that God is the best at making lemonade out of lemons and making as much good come out of tragedy as possible.”

Before the accident, when he was a teenager, Asberry had begun volunteering with the children’s ministry at Seagoville Road Baptist Church. He would lead the first- through sixth-graders in song or help teach the lesson in children’s church, “whatever they needed me to do,” he said. He felt God steering him toward a future as a pastor, and after the accident, he was sure of it.

“It made me remember, especially at 15 years old, that life is not promised,” Asberry said. “We went to more funerals in one week than most people do in a lifetime.”

After graduating from Balch Springs, Asberry enrolled at Baptist Bible College East in Boston, now called Boston Baptist College. But Boston was a big leap straight out of high school. He stayed a year, then moved back home, trying various jobs before landing on home restoration.

Through it all, his involvement in children’s ministry never wavered, but today he works as a division manager for G2 Restoration, a company that cleans up after fires or water damage.

“We have a tendency to meet people on the worst day of their life,” Asberry said. “It’s definitely a calling and a ministry.”

In 2012, Fielder Church found itself in need of a children’s pastor for its Grand Prairie campus and tapped Asberry. He juggled both pastoring and his restoration work for about two years before he resigned from the church. “There wasn’t enough time in the day,” he said.

But he has stayed as involved as possible. He is at every church service and on every youth trip his schedule allows, and he makes the most of the time he has with the kids.

On a recent Sunday morning, two young girls squeal as they run toward him. “Hey Mr. Chip,” they say, wrapping their little arms around his legs. He’s leading a group of kindergarteners through third-graders at Fielder Church’s children’s ministry.

Hillsong Kids plays from a video as children arrive. Some of them dance, quarter notes thumping beneath the lyrics:

No longer I but Christ in me

’Cause it’s the truth that sets me free

How could this world be a better place?

But by thy mercy and by thy grace.

Asberry stops mid-sentence when a blond boy he doesn’t recognize walks into the room. He crouches down and introduces himself, so the small boy feels seen.

He’s worked with kids of all ages, but Asberry prefers to teach the younger ones. “They haven’t formed an opinion one way or another,” he said. “Their love is pure. They’re not trying to be all cool.”

On this morning, the kids sit in miniature green chairs, girls on the left and boys on the right. “Good morning,” Asberry says in his deep, booming voice. A dozen kids scream the greeting back to him.

The lesson is about Adam and Eve.

Brittney Martin is a freelance writer based in Houston, Texas.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.