During Burundi’s civil war in the 1990s, I spent several months in a crowded camp for internally displaced people—people like me who had fled home but could not flee the country. One of my most painful experiences was to see fathers’ healthy masculinity shattered by the change in their lives.

Once the providers for their families, they now had to rely on relief food. They were deprived of their freedom of movement, unable to do what they had been doing all their lives (farming or business). Some began drinking heavily to deal with their depression.

I have since thought of Joseph, Mary’s husband, who also had to flee and deal with the frustrations of providing without stability. He could have become like those men. He could have resented his local and colonial governments for the ways they deprived him of good choices and made him move all over the region. He could have resented God for telling him to marry a woman who—his fellows might have said—deserved divorce and not his support. He could have tried to make up for his threatened masculinity with a lack of cooperation or with domineering legalism.

But that is not how the Scriptures portray Joseph. Instead, we see the man God selected to parent his son accepting God’s unexpected direction at each delicate step, not characterized by resentment but by wholehearted cooperation with God. I’ve seen how difficult that is. How did Joseph do it?

We don’t know a lot about Joseph. He is one of the biblical characters of whom very little is said. Not a political leader or a great prophet, his name would be absent from the Bible had he not been the guardian of the Messiah. Still, his lineage could have been a matter of pride and a basis for him to strive for a position of honor. In Luke’s account of the angelic visitation of Mary, Gabriel affirmed that Jesus was the promised descendant of David and that he would be given the throne of David and a kingdom that would have no end (Luke 1:31–33).

The fact that Matthew, a Jewish gospel writer and a disciple of Jesus, introduces Joseph as a descendant of David is significant (1:20). It puts Joseph in the spotlight of the divine plan for humanity as the adoptive father of the Messiah.

Apocryphal writings supply an unreliable, sometimes even angry, image of Joseph. Both the Protoevangelium of James and the History of Joseph the Carpenter assert that Joseph was a widower with children from a previous marriage. Those details about Joseph prop up the idea that Mary was a perpetual virgin, but there’s no reason from the Scriptures to think Joseph had previous children: The nativity accounts don’t list anyone besides Mary as traveling to Bethlehem with Joseph, and Joseph was asked to flee to Egypt with just Mary and Jesus (Matt. 2:13–15).

It is most likely that the real, nonapocryphal Joseph was an average Jewish young man, with some religious education. Rabbinic writings suggest that the expected age for marriage in Joseph’s time was the late teens. So Joseph was probably living with his parents or relatives when the angel told him to marry Mary. After Jesus was born, Joseph had four boys and an unknown number of girls with Mary (Matt. 13:55–56).

The Bible implies Joseph was a very ordinary man from an ordinary place, a village man who was known through his profession. People thought of him as “the carpenter” (13:55). His days were likely filled with hard work.

While the Jewish culture valued menial labor, the reality was totally different with the Romans, the colonizing power that ruled Palestine during Joseph’s life. From a Roman perspective, carpentry was a slave’s profession. So Joseph was far from being among the people with high status.

Some of that status he may have been born into, but some of it he may have chosen. Joseph lived during rough times, when opportunists could collaborate with the Romans and enjoy a materially comfortable life. He did not take the path that Matthew, the former tax collector, chose. Matthew, the writer of the Gospel that says most about Joseph, might have seen the temptation of collaboration most clearly. And yet, Joseph wasn’t needlessly uncooperative with the Romans. He went to the city of his ancestors for the government census, for example.

In this simple and useful lifestyle, he was confronted with the powers that be—the powers that were—who thrived on injustice, violence, and corruption. In that confrontation, Joseph’s spirituality becomes more evident, and God clearly stands with him.

Indeed, God is close to those who, like Joseph, are humble and contrite and who tremble at his word (Isa. 66:2). Simplicity, as a spiritual discipline, helps us avoid the enticement of materialism and enables us to focus on things that really matter. Those who practice simplicity can be wealthy without materialism and be descendants of the line of kings without competing with Herod. For them, righteousness is better than the glory of the world.

It seems clear to me Joseph was able to guide his family well because he was open to God and his messengers in a way that defied legalism. Joseph’s spirituality prepared him for the unexpected.

In strongly patriarchal cultures, men usually expect to be able to provide well for their families, sometimes with a good dose of emotional detachment from their wives, and they often expect their own plans to be the plans that direct their families. Heads of families can be rigid and resist unconventional behavior. In my culture, for example, though the winds of human rights have been blowing for more than two decades now, most Christian men still struggle to get rid of rigid patriarchal attitudes and behaviors, and some distort the Bible to justify those behaviors in themselves.

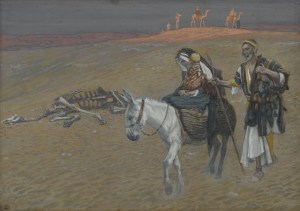

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsJoseph wasn’t like that. We see that most clearly in his treatment of Mary. As a Jewish man, Joseph understood what could happen to a girl who had sex before marriage (Deut. 22:13–21). Pregnancy was the most convincing proof of sexual misconduct. Legally, he would have been right to denounce Mary.

But to Joseph, Mary’s perceived sin did not make her an outcast. He knew she deserved love and protection. The NIV beautifully combines Joseph’s Jewish religious culture and his personal spirituality in one sentence: “Because Joseph her husband was faithful to the law, and yet did not want to expose her to public disgrace, he had in mind to divorce her quietly” (Matt. 1:19).

Here, we see that Joseph isn’t the grumpy, emasculated husband of Christmas legend. Even before he received God’s message about Jesus, Joseph’s demonstrated love for Mary and his commitment to protect her dignity overpowered any legalism. Joseph’s behavior portrays genuine masculinity and Bible-certified righteousness.

The situation, of course, isn’t what he had first imagined. In a dream, an angel told him Mary’s pregnancy was of divine origin. Joseph dismissed his previous plans and agreed to obey just as quickly and simply as Mary had accepted that she was pregnant before marriage (Matt. 1:24; Luke 1:38).

Such a positive response to such a difficult and risky circumstance would have been impossible in a spiritually dull, legalistic mind. A legalistic man might have quickly dismissed the angel’s message as hallucination, as it seemed to contradict the law. Joseph’s spirituality was of such a kind that he was able to value the will of the lawgiver more than the law, something that eluded many sophisticated theologians and religious leaders (Matt. 15:3–9), not to mention Jesus’ disciples.

When, in another dream, an angel ordered Joseph to flee to Egypt with Mary and the baby, Joseph obeyed and fled (Matt. 2:13–14). For many in Joseph’s position, the command would have seemed nonsensical. They expected a powerful, conquering Messiah, not a baby refugee (Acts 1:6).

That Joseph was able to set aside the common mindset because of a dream shows that his spirituality was deeper than the prevailing religious thought of the people of his time. He could tell when God had spoken to him directly. We see the simple village man cooperating with God to preserve the life of the Messiah.

We often see the Nativity as a celebration of comfort and innocence. In Europe and the United States, Christmas is often a time to think of coziness. In my country, it’s sort of a children’s holiday among evangelicals.

Could Joseph ever fit in with these modern Christmases? Certainly, we can say Joseph had the childlike humility that Jesus later praised (Matt. 18:4), and his simplicity and righteousness are a form of innocence. But Joseph parented Jesus in turbulent times. Perhaps our Christmases would be better if we remembered that innocence and responsiveness characterized the father God chose to guide a family through danger, not just children cuddled up in safety. Joseph surely knew how violent Roman rulers could be. On the roads, he may have passed by agonizing crucified people who, like his family, were a threat to the regime.

Because of a political decision of an emperor thousands of miles away, Jesus was born in overcrowded Bethlehem—a logistical headache for Joseph. It is possible that the couple traveled with relatives who were by their side when Jesus was born. But no mention is made of relatives helping Joseph tend Mary and the baby. When there wasn’t space for them in the guest room, Joseph didn’t have the wherewithal to do better (Luke 2:4–7). Later on, another political decision and another message in a dream caused Joseph to flee to Egypt with Mary and Jesus. Herod could not allow a child who could potentially challenge him on the throne to grow, and he targeted the baby for assassination.

Brooklyn Museum

Brooklyn MuseumFear, anguish, and a sense of powerlessness must have plagued Joseph’s tender heart when he became aware of the threat. Anyone who has lived through massive violence (as in the case of a civil war) knows the agony of the possibility of losing loved ones accompanied by the incapacity to protect them.

Anybody in Joseph’s place would have asked themselves existential questions and questioned their faith. Was he tempted to take his life, as some are when confronted with a similar situation? Did he think of migrating to a safer place and never returning to Palestine? Was he tempted to become passive or fatalistic? The combination of danger, grief, boredom, lack of meaningful work, heavy responsibility, and even heavier burdens have led many forcibly displaced people to react in these ways.

It is the spirituality of Joseph, beautifully mingling with the hardships he faced, that makes his story one of hope. He surely pondered the words of the angel: “So get up, take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt, and stay there until I tell you to leave” (Matt. 2:13, GNT). Part of this was an order; the other part was a promise. God was in control. One day, Joseph and his family would go back. The selfish and cruel rulers did not have the last word in the life of Joseph’s family.

And yet, Joseph and his family were in a delicate situation where he needed to depend on God to make the most basic decisions. One wrong decision could be fatal. When the time to go back came, the angel instructed Joseph to return (Matt. 2:19–20).

Again, Joseph was divinely guided to make a decision that was very dangerous. Anyone who has been a refugee recognizes this. In the camp for displaced people where I lived, some men left to resume their normal lives before the area was safe; their impatience cost them their lives.

The world was still the world—even at a moment of reprieve. God advised Joseph not to live in Judea, but in Galilee. There was no complete safety, no complete relief. Herod was dead, but his son was in power (vv. 21–23). God did not destroy all the wicked right then, but neither did he allow his plans to be thwarted by them.

Today, the world is in some ways better than it was during Joseph’s time. Human rights organizations can speak for the weak and help protect their lives. However, humanity is still fallen and, therefore, far less than perfect. The number of forcibly displaced people in the world has risen to a 40-year high. Wars, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes, pandemics, and the decisions of rulers can destroy our sense of safety and stability.

That said, we should never forget that God is at work and that he is with us even at our darkest hour (Ps. 23:4–5). Besides, he has promised to instruct us in the way we should go (Ps. 32:8) as instruments of his will on earth.

As God used Joseph, so does he intend to use us to carry out his purposes for our generation. But this requires of us the kind of spirituality that transcends denominational traditions and legalistic mindsets. We must also carefully avoid the snares of the flesh to remain sensitive to God moving in our time.

Just as God does not allow these things to separate us from him, we should not allow danger, insecurity, or even death to stop us from cooperating with him.

How can we do that? Not through complicated strategies, but with a faith like Joseph’s: a simple, childlike faith, ready to depend on God for the decisions we make, to do what he instructs us to do, and to go where he leads us without grumbling, whether it is comfortable or dangerous.

Acher Niyonizigiye is a pastor at Bujumbura International Community Church, a cofounder of the leadership nonprofit Greenland Alliance, and the author of Be Transformed and Glorify God with your Life.