Many American evangelicals love C. S. Lewis’s writings yet balk at his depiction in The Last Battle of Emeth, the soldier who gets to enter Narnia’s heaven despite having followed the god Tash and not Aslan the lion.

Yet such theological inclusivism (often misrepresented as universalism) is now supported by a quarter of evangelicals and a majority of mainline Protestants and Catholics, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

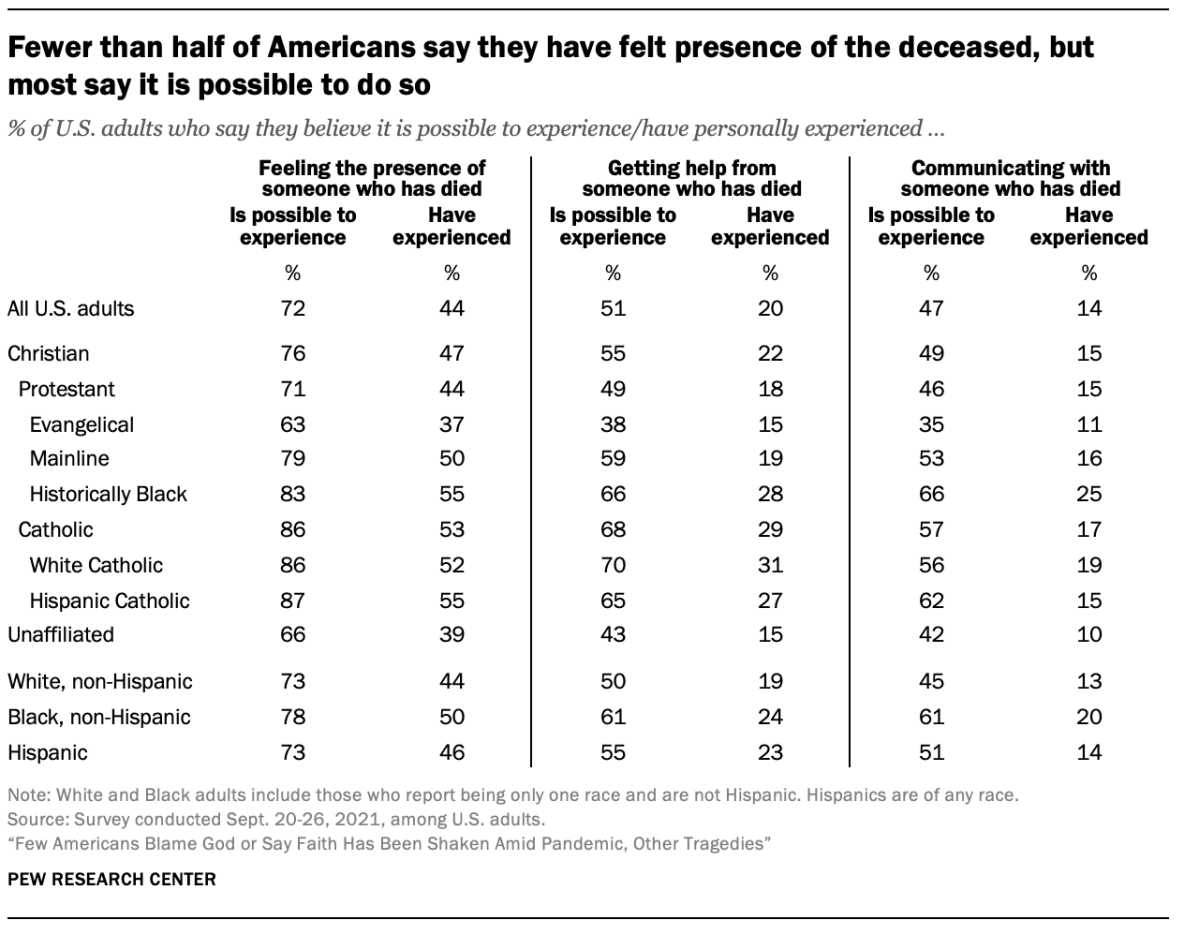

Most Americans more or less believe that “hell is other people” (apologies to Sartre), according to Pew’s pandemic-inspired study, released today, on suffering and the problem of evil.

Yet when it comes to the actual hell and heaven, in the same survey Pew found “many Americans believe in an afterlife where suffering either ends entirely or continues in perpetuity.”

Pew surveyed 6,485 American adults—including 1,421 evangelicals—in September 2021 about the afterlife, specifically their views on heaven, hell, reincarnation, fate, prayer, and other metaphysical matters.

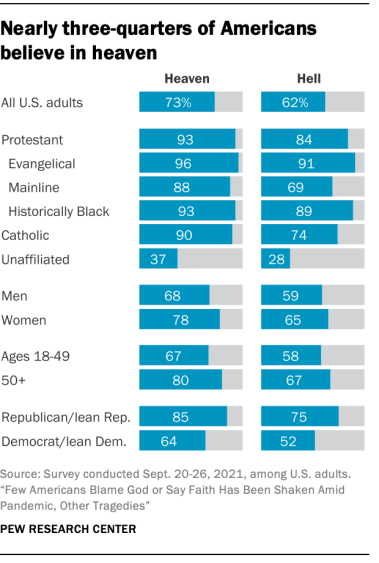

Today 73 percent of Americans believe in heaven while 62 percent believe in hell, similar to 2017 when Pew last asked the questions.

As mentioned in the preface of last month’s article by Barbara Thompson on the Bruderhof, which focused on that community’s understanding of the place of the Christian within the nation, the initial presentation of the Christianity Today Institute will address the subject of “The Christian As Citizen.” Featuring the insights of evangelical scholars and practitioners, this special institute supplement will appear in the April 19 issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY.

As mentioned in the preface of last month’s article by Barbara Thompson on the Bruderhof, which focused on that community’s understanding of the place of the Christian within the nation, the initial presentation of the Christianity Today Institute will address the subject of “The Christian As Citizen.” Featuring the insights of evangelical scholars and practitioners, this special institute supplement will appear in the April 19 issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY.In anticipation, the following article by Stephen Monsma, who was himself a participant in the first meeting of the institute, deals with the relationship between faith and political decision making, politics and government, from a Reformed perspective.

“Dirty politics” is a phrase that is almost as common as “Merry Christmas.” In fact, we have a whole stable full of terms with negative connotations that we often use to describe political phenomena: “smoke-filled rooms” instead of “conference rooms,” “political hacks” instead of “political organizers.”

From my own experience as a legislator in both the Michigan State House and Senate, I can testify that the political process is often seamy and even sordid.

The problem is that the system, with its interlocking network of attitudes and expectations that permeate our political institutions and practices, creates an atmosphere where such ideals as justice, righteousness, order, and servanthood are absent. Thus those who struggle for these ideals do not face their biggest challenge from some particularly dramatic, clearly labeled evil, but from nebulous, all-pervasive attitudes and expectations. Evil is everywhere and nowhere. It is everywhere in that it is pervasive and ever-present; it is nowhere in that it can come to appear so natural and so much a part of the political atmosphere that it goes unnoticed, like the air we breathe. The God-inspired political struggle for greater justice thereby becomes a spiritual struggle against “the powers of this dark world,” against seemingly all-powerful, intractable forces, forces of parochial self-interest, ponderous inertia, and organized special interests.

Christians are called to redeem politics in the name of Jesus Christ, empowered to transform, not to be conformed to the world of politics as it is.

There are five basic characteristics of the political process, often misunderstood and always open to abuse. To redeem politics successfully, we need to consider politics as combat, as compromise, as teamwork, as public relations, and as representation.

Politics As Combat

Political decisions are decisions that deeply affect the lives and values of people and groups in society—as when a government contract is gained or lost and employment or unemployment results, or a toxic-waste dump is or is not built in one’s neighborhood.

Because vitally important decisions are made in the face of sharply divergent views, struggle or combat results. And because the stakes are often very high in politics, people regularly risk health, financial security, and family in order to pursue political goals. The Watergate scandal vividly demonstrated the lengths to which people will go for persons and causes they believe in.

In its unredeemed state, the combativeness of politics can easily degenerate into a struggle dominated by people’s selfish ambitions and marked by nothing more substantive than macho swagger. The political world is largely male, dominated by people whose primary goals are all too often getting reelected, amassing greater personal power, and commanding the ego-satisfying deference that comes with political power.

If a person is not clearly and self-consciously committed to pursuing his or her vision of a just order, a truly good society, it is almost inevitable that this person will soon be wallowing in the mire of selfish ambition, using the issues and the needs of society to help assure his political survival and build his political power.

But when politics has been brought under the lordship of Jesus Christ, one’s political struggles are focused and directed by one’s tenacious drive for a more just order. It is a struggle—often an exhausting, frustrating, debilitating struggle—but one with a goal firmly rooted in moving society toward greater justice. In the process one becomes a servant of those suffering injustice.

This does not mean that one should squander all political influence pursuing clearly unattainable goals (although at times our Lord may call us to do exactly that). We are called to be wise, perhaps even wily, not for the purpose of advancing ourselves, not to gain more power for power’s sake, but to advance God’s cause of greater justice in society. This is the essence of political servanthood.

Politics As Compromise

A second basic characteristic of politics is compromise. It plays a crucial role in politics because it is the means by which differing individuals or groups are able to resolve their differences and reach agreement.

For Christians, who have been taught to struggle for the clear, absolute truth of the Bible, the very word “compromise” has a somewhat unsavory ring to it. In a struggle of justice against injustice, is not any compromise an unacceptable accommodation to evil? I would say no. I can easily picture certain conditions where a compromise would be completely compatible with redeemed politics. In fact, it can be argued that politics based on negotiated compromises is often preferred.

One must not picture the political arena as involving the struggle of absolute good versus absolute evil, of total justice versus total injustice. The real world is never that simple. Typically, even the Christian politician pursuing justice in a sinful world feels caught in a dense fog. He or she has a fairly good sense of justice and what it means on the contemporary scene. But the questions public officials face come in specific, concrete, often technical forms. In such situations—with important information missing and values clashing—even the Christian public official has only a partial idea of what is needed. And then he or she may be mistaken.

Sometimes Christians enter the political arena with a very rigid, explicit vision of what they believe needs to be accomplished. And they pursue that vision with a self-confidence that becomes arrogance. This is wrong. One mark of Christians in politics should be a sensitivity to their own limitations and fallibility. God’s Word is truth. The principle of justice is absolute. But our applications of God’s truth and of his standard of justice are often fumbling and shrouded in the fog produced by extremely complex situations, missing information, and the pressures of limited time.

What does all this have to do with compromise? Simply this: When one is asked to compromise, one is not being asked to compromise absolute principles of right and wrong. Instead, one is being asked to compromise on groping, uncertain applications of basic biblical principles. There is a big difference.

As a state senator, I was the sponsor of drunk-driving reform legislation in Michigan. In order to get the bills through the Senate, I had to take out one of the key provisions: allowing the police to set up checkpoints at random and to give every driver passing by a sobriety test. Then in the House Judiciary Committee I had to give up mandatory prison terms for convicted drunk drivers—even for drunk drivers who had killed another person. But much was left in the bills, including long-term, mandatory revocation of the licenses of convicted drunk drivers and stronger enforcement tools for the police and prosecutors. Some criticized me for giving away too much, but I defended what I did on two grounds. One was that if I had held firm I probably would not have gotten any bills passed at all. I was operating according to the “half a loaf is better than none” philosophy, and I believe it is appropriate. One pushes constantly, insistently, for more just politics, but progress comes step by step instead of in one fell swoop. As soon as one step is taken, one begins exerting pressure for the next. No bill, no action is seen as the end of the matter. One grabs as much justice as one can today, and comes back for more tomorrow.

But I also justify this approach on a second ground: this step-by-step evolution of policies is less likely to lead to unanticipated, negative consequences. That quantum leap into the future that I may think will usher in the ultimate in justice may, if I could attain it, prove to be a disaster—or at least much less than the vision of true justice I had in mind. Thus the more cautious step-by-step approach that the realities of politics usually force us to take is really not all bad. There is something to be said for giving the police some additional tools with which to deal with drunk drivers, assessing their effectiveness, and then deciding whether or not sobriety checkpoints and mandatory prison terms are also needed. The more guarded approach I was forced to take has its good points.

The compromising nature of politics gets one into trouble when one is really not concerned with issues at all but is only interested in his or her selfish ambitions. Then a person will be willing to compromise as long as another bill is passed to his or her credit.

Under such circumstances compromise is used not to push for as much justice as one can get at that time but to satisfy one’s own selfish desires. Justice is displaced by personal ambition and pride.

In summary, negotiated compromise is a frequent outcome of political combat. In its redeemed form, politics as compromise works insistently, persistently, for increased justice in a step-by-step fashion, recognizing that some progress toward greater justice is better than none at all, and that small, incremental steps toward justice may be a wiser stride than giant quantum leaps, which run the danger of going down false paths. But in its unredeemed form, compromise is used to give the illusion of progress or change merely to build up one’s reputation and to feed one’s selfish ambitions.

Politics As Teamwork

A third basic characteristic of politics is teamwork. Working for greater justice through political action is not an individual enterprise but a joint or group process. Almost any political project one can undertake involves building a coalition among like-minded individuals and groups.

Saying this much appears to be stating the obvious. Yet many of the most difficult moral dilemmas and, I suspect, much of the unsavory reputation of politics arise from this very characteristic. The danger is that in allying oneself with certain individuals and groups one will incur debts that will compromise one’s basic independence and integrity.

All elected officials have a coalition of support groups to whom they turn for campaign funds and volunteers and for help in getting legislation passed. They will vary greatly depending on the background, political philosophy, and partisanship of the individual, but all elected officials are backed by certain coalitions or “terms.”

But this relationship between public official and supporting coalition cannot be simply a one-way street. One cannot expect individuals and groups to be at one’s beck and call, ready and eager to offer support and help, without them, in turn, having a say about what one is doing. Sometimes even the conscientious, justice-oriented official votes or acts differently or alters the strategies he or she pursues out of deference to one or more groups or individuals.

The Right-to-Life organization is one group that I have worked with very closely throughout my political career. It is part of my coalition or team. Once this relationship resulted in my leading the struggle in the senate for a bill to forbid the spending of tax money to pay for Medicaid abortions, even though I would have preferred to accomplish this by other means. I thought we should have tried to discharge the committee that had bottled up this legislation. But the majority leader of the senate opposed this, and the consensus of the Right-to-Life leadership was to insert the desired language in another bill that was in another committee more favorable to our position. The only problem was that doing so probably violated senate rules, and one could question whether the new language was germane to the intent of the original bill. We had the votes, so we pushed the new language through by overturning a ruling of irrelevancy by the lieutenant governor. I ended up in the uncomfortable position of having to argue on the floor of the senate and to the news media that something was germane when I and everyone else knew it probably should not be considered germane according to past senate decisions. Yet I did so, and I still believe I did the right thing, because the team that I had joined, the coalition that I was a part of, had jointly decided that this was the way to go. A politician is not a prima donna but a player in an orchestra.

There are, I believe, two key requirements that a politician must meet to avoid slipping into practicing unredeemed politics, to be able to transform the team aspect of political activity. First of all, the individuals and groups with which one allies oneself must be those whose basic principles and basic orientations on issues are in keeping with the promotion of a more just order. Politicians guided by selfish ambition will select teams or coalitions that will add most to their clout, those with money, prestige, and connections.

A second requirement is that one must place strict limits on the extent to which one will modify one’s positions or tactics to accommodate a group decision. In the situation described earlier, I was willing to fight for a germaneness ruling that was probably not in keeping with senate rules and precedent. But I would not have been willing to fight for a ruling that would be contrary to the state constitution or basic justice.

Yet those who practice unredeemed politics put such a strong emphasis on their personal ambitions that they would not risk losing a key person or groups of their coalition by refusing to go along, even if they disagreed with the position on a crucial, fundamental issue. They are no longer team members, parts of coalitions; they are prostitutes. They have sold themselves to their supporters.

In summary, politics means teamwork, and teamwork means working with others and even modifying one’s own positions to maintain the unity of one’s team. But in its unredeemed form this is done only with an eye to enhancing one’s own selfish ambitions. If it is to be redeemed, political teamwork must occur in the context of shared fundamental ideals and within reasonable boundaries.

Politics As Public Relations

Anyone in politics is under constant pressure to please and to look good to the public, to key individuals and groups, and to the news media. This is important for reelection. But it is also important for less obvious but equally significant reasons. Life is easier and political influence is greater when one is very popular. Psychologically, we all need the reassurance that we are okay, that we are good people doing a good job, and we all cringe when we are ridiculed or criticized. Politicians are certainly no exception.

Thus, politically active people are sensitive about their public relations. They strive not only to do a good job but to ensure that the general public, the news media, and their friends and supporters realize what kind of job they are doing.

In its unredeemed form this characteristic of politics can turn politics into nothing more than one big con game. Politics often takes place on two quite separate tracks. One track is the world governed by people’s values, the realities of the world as it is, powerful interest groups, and powerful political figures. The other track is the world of appearances, of public profiles and rhetoric. Very often the two are quite different.

Typically, the worst time for these sorts of flimflam games is during election campaigns. Often the operating procedure seems to be, “Say whatever will get you a few more votes. No one will notice whether or not what you are saying back home squares with the way you vote in Washington or the state capitol.”

I am convinced that politics does not have to operate on this sort of two-track system, that it does not have to be a big con game. But it takes the transforming power of Jesus Christ to say no to this kind of politics.

Working to maintain good public relations can be a proper characteristic of politics. The political struggle in a democracy is and should be waged in the glare of publicity. This means that even Christian politicians must be concerned about their public relations, about their images, and how people and the news media are perceiving their actions. But the Christian politician, it he or she is to be faithful to the Lord, must ensure that public appearances are an accurate reflection of what he or she really is and is really doing. Honesty is the key term here. That must be the inviolable standard. Nothing less will do.

But one cannot assume that simply doing right will automatically ensure that the public will perceive one favorably. Two factors are involved here. First, one has to communicate to the public who one is and what one stands for. It is easy for a politician to cause the public to think an opponent is someone he or she is not. At various times in my political career I have been accused of being soft on crime, being in league with the pornography industry, accepting illegal campaign contributions, and being opposed to nonpublic Christian schools. All of these charges are false, but unless one has some means to respond to such charges or has built up quite a different image, one could soon become the victim of such charges.

A second factor is that one is periodically in a situation where he or she will have to take an unpopular stance. Through good public relations one can build up capital, minimize criticisms, and stress the positive advantages of the stance.

In summary, politics as public relations grows out of the open public nature of the political process. In its unredeemed form, politics as public relations degenerates into a big con game marked by attempts to deceive the public into seeing one’s actions as something other than what they really are. In its redeemed state, politics as public relations accurately reflects who one is and what one is doing, but does so in such a way that one’s public image is improved.

Politics As Representation

The United States is ruled by a representative form of government. The members of Congress’s lower house are called representatives. Presumably they represent not themselves, not their own ideas of right and wrong, but the people who have elected them.

This concept of governing creates a problem, perhaps even a dilemma. What happens when a majority of the people who elected a representative are clearly in favor of an unjust policy? One is supposed to represent them—this is a cornerstone of the system of democratic government. Yet one entered politics in order to pursue justice. Is this to be sacrificed when 51 percent of one’s constituents take an opposite position? Presumably not. But if one does not do so, has not he or she supplanted democracy with an elitism that assumes that the politician knows better than the people who elected him or her?

Before suggesting an answer, I should point out a crucial factor. The dilemma of the previous paragraph made three assumptions, all of which are false: that all people have opinions on key public-policy issues, that those opinions are known to public policymakers, and that the intensity with which people hold an opinion and the knowledge on which they base it ought not to affect the policymaker.

In fact, on most public-policy issues a majority of the public will have either no opinion at all or a lightly held, ever-shifting opinion. Public opinion polls have found that on issues that have not been dominating the news for months, slight differences of wording in the questions can result in big differences in the public’s responses. What does representing the public mean in situations like this?

To add to the difficulty, one can never be certain what the state of opinions back home are on any given issue. Legislators receive letters from their constituents. They meet frequently with constituent groups, and their friends feel free to give their opinions. There are periodic public opinion polls. But almost invariably they encompass larger areas than one’s legislative district. The result is a fuzzy notion of what people back home are thinking. But add this to the shifting, uncertain nature of public opinions themselves, and even the representative determined to reflect accurately whatever the hometown public is thinking is usually left in a thick fog.

Still more confusing is the factor of intensity. Suppose 60 percent of the people (we will assume perfect knowledge about the percentage) favor one side of an issue, but do not have much knowledge or strong feelings about it. And 20 percent know the issue well and take very strong opposite positions. But the other 20 percent of the public has no opinion at all. Should the legislator who is trying faithfully to reflect the public’s feelings side with the marginally committed 60 percent or the intensely committed 20 percent? Abstract theories of representation have no answer. Ought not both the strength of one’s opinion and the amount of knowledge on which it is based count for something? The 20 percent, because of the strength of their beliefs, are probably writing many more letters, meeting with their representatives, and in other ways expressing their opinions, while the 60 percent are largely sitting back, uninvolved.

This in fact is precisely the situation that exists in regard to gun-control legislation. Public opinion polls regularly show a clear majority of Americans in favor of stricter gun-control legislation. But the minority that is opposed to further gun control believes in its position much more strongly and is much more willing to act on its beliefs than is the majority that favors stricter gun controls. If I were seeking merely to reflect the opinions of the people I represent, should I be for or against further gun control?

Given this muddled picture, let us turn to the meaning of politics as representation.

In its unredeemed form, politics as representation asks how one can use or manipulate public opinions to maximize one’s chances of election or reelection and to increase one’s political power. Thus, one will naturally avoid going against strongly held public opinions. Intensity becomes the key factor. Only people who feel intensely about an issue are likely to vote for or against a legislator and are likely to write a nasty letter to the editorial column of the local newspaper if the legislator takes the “wrong” position. Special weight will also be given to the opinions of past or potential campaign contributors or powerful people in the community.

What must also be factored is potential intensity. An issue may be attracting very little attention, but if it can be used by an opponent in the next election to make one look bad in the eyes of many voters, the person guided by selfish ambitions will be very concerned.

Thus, in unredeemed politics, the politician is constantly on the alert to use issues to build support or avoid losses and justify these actions on the basis of representing the people. But the principal motivation here is really a selfish desire to strengthen or solidify one’s political base.

In redeemed politics one follows one’s conception of justice, not the leanings of public opinions. If necessary, one should go against the wishes of that majority and support the side of justice. To do otherwise would negate the entire point of having a justice-oriented Christian in public office. Each vote and each position a justice-oriented legislator takes should be saying, “This is what I believe is right and just,” not “This is what I believe most people in my district are in favor of.”

But more needs to be said. The Christian legislator can easily fall victim to an arrogant elitism in which the prevailing attitude is, “Look, I know what’s best for you. So you just be quiet and accept what I know is right. After all, I’m following biblical justice.” Such an attitude is wrong and would set redeemed, justice-oriented politics at odds with democratic politics.

There needs to be a strong sense of Christian humility based on an understanding of one’s own fallibility and limited knowledge. The Christian legislator should vote according to his or her own convictions of justice, but he must first ask himself, “What am I missing that so many others are seeing?”

There is an old Indian proverb that one should not criticize another until one has walked in the other’s moccasins. Similarly, policymakers who are true servants of those whom they represent will act only after walking and talking open-mindedly with those for whom they are making decisions. Sometimes doing so will make them change their minds. When policymakers take this servantlike attitude, justice-oriented politics is saved from degenerating into an arrogant, elitist politics. True representation still exists.

However, the representation process should not be a simple one-way street. Constitutents can often help educate and broaden the perspective and knowledge of their representative, but the representative can do the same for those whom he or she represents. In redeemed politics the representation process is a creative, two-way street. Through personal meetings, telephone conversations, responses to letters, and statements to the media, legislators are able to share with their constituents what they have learned in Washington or at the state capitol. The public tends to be narrow in perspective. The legislator, on the other hand, is forced to view things from a much broader perspective, and thus has a responsibility to share that perspective with his or her constituents. A valuable two-way communications system is thereby created.

Politics as representation is important. Christian, justice-oriented public officials are representatives. But this does not mean that they slavishly follow the shifts in public opinion, nor that they pacify people with strong opinions, only to head off possible adverse public reactions, and that to protect their selfish political interests. Instead, Christian public officials redeem the political process by pursuing justice, while taking time to dialogue with those whom they represent, willing both to lead and to be led by them.

Politics that is enslaved to the powers of this dark world and politics that has been redeemed by Jesus Christ differ widely because they follow two entirely different standards. The politics of this world is based on selfish ambitions—getting ahead, building one’s political power, expanding one’s base. The politics of our Lord is based on servanthood and justice. Justice is the goal. Subordinating personal needs and desires to pursue that goal, one becomes a servant.

Meanwhile, 1 in 4 Americans don’t believe in heaven or hell. Instead, 7 percent believe in “a different kind of afterlife” while 17 percent don’t believe in any afterlife.

According to Pew researchers:

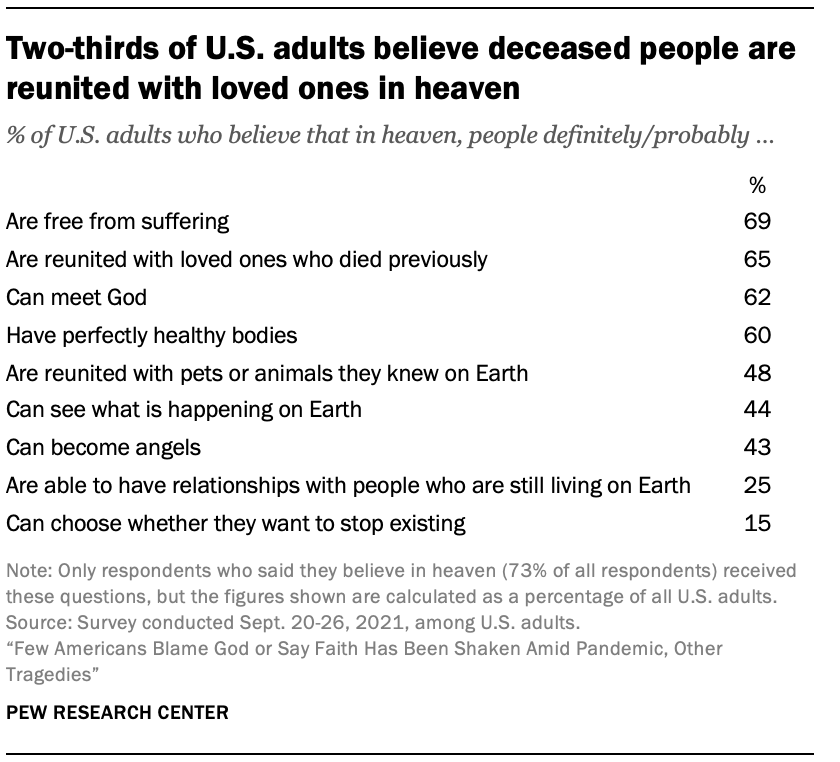

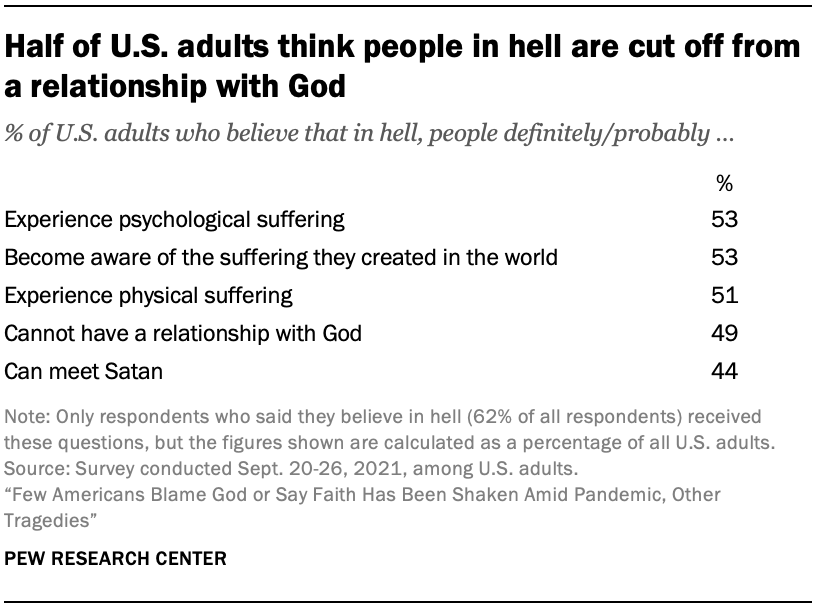

The vast majority of those who believe in heaven say they believe heaven is “definitely” or “probably” a place where people are free from suffering [69%], are reunited with loved ones who died previously [65%], can meet God [62%], and have perfectly healthy bodies [60%]. And about half of all Americans … view hell as a place where people experience psychological and physical suffering [53%] and become aware of the suffering they created in the world [51%]. A similar share says that people in hell cannot have a relationship with God [49%].

Four in 10 Americans believe those in hell definitely or probably can meet Satan.

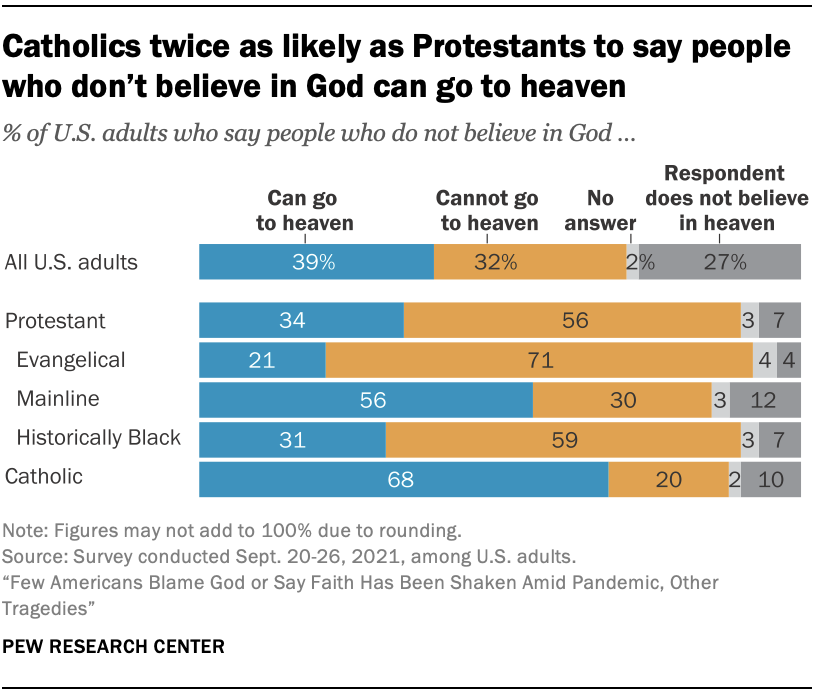

Meanwhile on the fate of nonbelievers, Pew found support for inclusivism among Catholics was “far more likely” than among Protestants (68% vs. 34%), and especially evangelicals (21%).

Billy Graham discusses hunger, racism, peace, revival, and evangelismThe log house belonging to evangelist Billy Graham sits at the end of a long road slithering up to the crest of Black Mountain. It is a sturdy and warmly appointed place surrounded by thick stands of hardwood and jackpine and blooming mountain laurel. One can hardly imagine, peering through the ethereal haze draping the hills of this North Carolina hamlet, a more idyllic and soulful setting for a retirement home.But for Graham, who now is 66 years old, his all-too-infrequent visits to the family homestead in Montreat provide him only the barest respite from his relentless public and private journeys. As long as he is persuaded the hand of God is upon him, the evangelist says he is dutybound to continue his ministry of preaching throughout the world, adding to the flock of 100 million people who have poured in to his crusades.It has been for him an astonishing and supernatural run as the twentieth century’s most recognized and decorated preacher, confidant to presidents and royalty, and counselor to millions of common folk. But Graham says he will be content with a simple epitaph for his life and ministry: “A sinner saved by grace; a man who, like the psalmist, walked in his integrity. I’d like people to remember that I had integrity.”Still, there is much to do. It is, the evangelist says, “God’s hour for the world,” a time of unprecedented danger and new opportunities, of thunderous approaching hoofbeats and wondrous breakthroughs for the cause of Christianity.He worries that the world stands at the brink of nuclear holocaust. He laments a resurgence of racism and the uneasy peace in South Africa. He wonders about the morality of the distribution of wealth on the globe, and anguishes over the economic disparities in his own homeland. Yet somehow, through it all, he sees signs of hope.He has, in fact, changed in considerable ways since he burst from the halls of Wheaton College in 1943 to take charge of his first pastorate in the nearby Chicago suburb of Western Springs. He became the pastor of the First Baptist Church, a small congregation in a town dominated by parishes of a more mainline stripe. Even then Graham was dropping broad hints that he would not be content with a merely parochial ministry. He was instrumental in changing the name of the congregation to the Village Church in an effort to attract fallen-away Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Methodists who may not have known of the Baptist denomination or who may have harbored a bias against it.Since those early days, Graham has become something of a patriarch for the whole of American Protestantism, admired chiefly by adherents of the more conservative and evangelical faction, but also regarded with growing respect by members of many more liberal denominations. His most persistent detractors, in fact, have been religious extremists largely from the far Right, who fault Graham for his long-standing cooperation with mainline churches that help sponsor his city crusades. More recently, those same critics have charged him with being naïvely soft on communism in the after math of Graham’s widely publicized trips to the Soviet Union and his other forays into Eastern bloc countries.“You can’t help but grow and become more tolerant,” Graham asserts. “Man is really the same the world over, and the gospel is universal in its application. It’s been amazing to me to find believers in every part of the world we’ve been to. There is no force in the world that can destroy Christianity, and history has proven that.”But even as Christianity appears to be advancing in other nations, Graham acknowledges he is dismayed by widening divisions among American Christians and an increasingly sullied image of conservative Protestantism due to the “proliferation” of theologically unsophisticated and often crassly commercial television preachers.“We may be in danger of returning to an Elmer Gantry image as far as evangelism is concerned,” Graham says. “In the 1950s and 1960s, I believe we contributed some to the erasing of that image.” But with the expansion of electronic media ministries in the past decade, and the emphasis by some on “emotion and money,” the cause of Christianity suffers, frets Graham, and all evangelical preachers are viewed with suspicion and often held up to ridicule.“The word ‘evangelical’ is hard to define now” in this new ethos, he says.In addition, the baldly partisan political lobbying in many of America’s churches has exacted a price, Graham says, noting that the toll is one with which he is himself intimately acquainted. “In the political arena, I think there were pastors and evangelists who went too far, both from the Left and from the Right,” in the 1984 national campaigns.Graham, of course, was assailed by many religious leaders for functioning in the role of unofficial White House chaplain through several successive American administrations. For the past decade, Graham has kept a discreet distance from the corridors of power in Washington, D.C., maintaining that even the perception of partisan political activity weakens his credibility as a preacher interested in communicating to people of every ideological tinge and cultural background.Even so, he has become increasingly outspoken on a number of moral issues with political implications, including abortion, multilateral disarmament of nuclear weapons, and the U.S. economic system. And Graham is now pledging to incorporate these controversial questions ever more forcefully into his sermons.“The weapons are getting more dangerous,” he contends, “and I’m more interested in the subject of peace now than I was two or three years ago. I’m not so worried about a war between the United States and the Soviet Union, but I’m thinking of a country like South Africa. If they get their back to the wall, would they use the bomb? What about Pakistan? Or certain countries in the Middle East? They claim that now at least 15 countries have nuclear weapons, and any one of them could draw in the superpowers.” Because President Ronald Reagan holds impeccable credentials as an unyielding anti-Communist, adds Graham, he has an important opportunity to negotiate arms reductions with the Soviets as a capstone of his administration, “just as Nixon was able to establish relations with the People’s Republic of China.”Graham further is vowing to assail, on moral grounds, the burgeoning federal budget deficit—calling at the same time for a reexamination of the American lifestyle. “We’re going to see this deficit making a tremendous impact on this country’s economy, and it’s going to affect everyone,” he predicts. “We’ve been living way above our means. And this inequity (between the wealthy and the poor within the U.S., and between America and most of the rest of the world) is going to have to change somehow, whether voluntarily or by law. You can’t have some people driving Cadillacs and others driving oxcarts and expect peace in a community. There is a crying need for more social justice.”By the evangelist’s own admission, the U.S. economy, currently under a much-discussed study by the nation’s Roman Catholic bishops, is a vexing and complex problem beyond his understanding. “The solution is beyond me, but I’ve found about 250 verses in the Bible on our responsibility to the poor.”During his crusade in Vancouver, British Columbia, last fall, Graham collected foodstuffs during a “Feed the Hungry” evening meeting to distribute among the poorest residents of that Canadian city. “It was a symbol to preach the message that we want to do something concrete,” he recalls. “We’ve got to have a plan to do this year-round, to help the street people. For most evangelicals, the problem is not motivation, but rather how to do something to help others. They’ve got the gospel—the Cross to transform the heart—and they are finding there are obligations that come with it.”For the past several years, Graham has been stressing with new vigor the themes of self-denial and social responsibility along with his familiar salvation message. “For me, it’s not just accepting Christ as Savior and Lord, but being a Christian every day,” says the evangelist. “I want to emphasize the price you have to pay, and the changes that must occur in your life.”Throughout his ministry, Graham has proclaimed the need for personal and corporate revival, and has long seen glimmers of proof that such changes are in the wind. But today, he says, the entire world is in the throes of a broad and authentic search for transcendent meaning, and the nation is on a religious quest of “major proportions—maybe the greatest of American history.” But the search for the divine “takes many forms,” Graham observes. “They may be turning to a guru somewhere and dabbling in metaphysical philosophy. We have both the false and the true Christianity, side by side—the wheat and the tares. People are hungry for a genuine religious awakening, especially university students. There is a nuclear cloud hanging over these students, and I sense a great fear of war and fear for our future far greater in Europe than in America.”Graham, who has preached in more than 60 countries, has been focusing much of his evangelistic energy in recent years outside the borders of the U.S. He conducted only one American crusade last year (in Anchorage, Alaska), drawing fewer than 10,000 a night; while his appearances in Mexico, Great Britain, South Korea, the Soviet Union, and Canada attracted, in most cases, surprisingly large numbers. This year, in addition to his recently concluded Fort Lauderdale campaign, the evangelist is crusading in Hartford, Connecticut, in May, and Anaheim, California, in July, as well as venturing back to England, Hungary, and Romania.Graham admits that in his youth he “came close to identifying the American way of life with the kingdom of God.” But with his far-flung excursions and his unusual opportunity to observe the Christian church in differing political systems, “then I realized that God had called me to a higher kingdom than America. I have tried to be faithful to my calling as a minister of the gospel.”And the gospel that Graham is now preaching with revitalized determination is a more demanding gospel, stripped of any coating of cheap grace and more subdued in its appeal to the emotions. “I had no real idea that millions of people throughout the world lived on the knife-edge of starvation and … that I have a responsibility toward them,” Graham asserts. “I’ve come to see in deeper ways some of the implications of my faith and the messages I’ve been proclaiming.”It is a gospel rich with the symbols and story of Holy Week, the account of deepest gloom and unspeakable joy, of death and resurrection. It is a message Graham intends to carry to the nations as long as he is given the breath to proclaim it.

Billy Graham discusses hunger, racism, peace, revival, and evangelismThe log house belonging to evangelist Billy Graham sits at the end of a long road slithering up to the crest of Black Mountain. It is a sturdy and warmly appointed place surrounded by thick stands of hardwood and jackpine and blooming mountain laurel. One can hardly imagine, peering through the ethereal haze draping the hills of this North Carolina hamlet, a more idyllic and soulful setting for a retirement home.But for Graham, who now is 66 years old, his all-too-infrequent visits to the family homestead in Montreat provide him only the barest respite from his relentless public and private journeys. As long as he is persuaded the hand of God is upon him, the evangelist says he is dutybound to continue his ministry of preaching throughout the world, adding to the flock of 100 million people who have poured in to his crusades.It has been for him an astonishing and supernatural run as the twentieth century’s most recognized and decorated preacher, confidant to presidents and royalty, and counselor to millions of common folk. But Graham says he will be content with a simple epitaph for his life and ministry: “A sinner saved by grace; a man who, like the psalmist, walked in his integrity. I’d like people to remember that I had integrity.”Still, there is much to do. It is, the evangelist says, “God’s hour for the world,” a time of unprecedented danger and new opportunities, of thunderous approaching hoofbeats and wondrous breakthroughs for the cause of Christianity.He worries that the world stands at the brink of nuclear holocaust. He laments a resurgence of racism and the uneasy peace in South Africa. He wonders about the morality of the distribution of wealth on the globe, and anguishes over the economic disparities in his own homeland. Yet somehow, through it all, he sees signs of hope.He has, in fact, changed in considerable ways since he burst from the halls of Wheaton College in 1943 to take charge of his first pastorate in the nearby Chicago suburb of Western Springs. He became the pastor of the First Baptist Church, a small congregation in a town dominated by parishes of a more mainline stripe. Even then Graham was dropping broad hints that he would not be content with a merely parochial ministry. He was instrumental in changing the name of the congregation to the Village Church in an effort to attract fallen-away Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Methodists who may not have known of the Baptist denomination or who may have harbored a bias against it.Since those early days, Graham has become something of a patriarch for the whole of American Protestantism, admired chiefly by adherents of the more conservative and evangelical faction, but also regarded with growing respect by members of many more liberal denominations. His most persistent detractors, in fact, have been religious extremists largely from the far Right, who fault Graham for his long-standing cooperation with mainline churches that help sponsor his city crusades. More recently, those same critics have charged him with being naïvely soft on communism in the after math of Graham’s widely publicized trips to the Soviet Union and his other forays into Eastern bloc countries.“You can’t help but grow and become more tolerant,” Graham asserts. “Man is really the same the world over, and the gospel is universal in its application. It’s been amazing to me to find believers in every part of the world we’ve been to. There is no force in the world that can destroy Christianity, and history has proven that.”But even as Christianity appears to be advancing in other nations, Graham acknowledges he is dismayed by widening divisions among American Christians and an increasingly sullied image of conservative Protestantism due to the “proliferation” of theologically unsophisticated and often crassly commercial television preachers.“We may be in danger of returning to an Elmer Gantry image as far as evangelism is concerned,” Graham says. “In the 1950s and 1960s, I believe we contributed some to the erasing of that image.” But with the expansion of electronic media ministries in the past decade, and the emphasis by some on “emotion and money,” the cause of Christianity suffers, frets Graham, and all evangelical preachers are viewed with suspicion and often held up to ridicule.“The word ‘evangelical’ is hard to define now” in this new ethos, he says.In addition, the baldly partisan political lobbying in many of America’s churches has exacted a price, Graham says, noting that the toll is one with which he is himself intimately acquainted. “In the political arena, I think there were pastors and evangelists who went too far, both from the Left and from the Right,” in the 1984 national campaigns.Graham, of course, was assailed by many religious leaders for functioning in the role of unofficial White House chaplain through several successive American administrations. For the past decade, Graham has kept a discreet distance from the corridors of power in Washington, D.C., maintaining that even the perception of partisan political activity weakens his credibility as a preacher interested in communicating to people of every ideological tinge and cultural background.Even so, he has become increasingly outspoken on a number of moral issues with political implications, including abortion, multilateral disarmament of nuclear weapons, and the U.S. economic system. And Graham is now pledging to incorporate these controversial questions ever more forcefully into his sermons.“The weapons are getting more dangerous,” he contends, “and I’m more interested in the subject of peace now than I was two or three years ago. I’m not so worried about a war between the United States and the Soviet Union, but I’m thinking of a country like South Africa. If they get their back to the wall, would they use the bomb? What about Pakistan? Or certain countries in the Middle East? They claim that now at least 15 countries have nuclear weapons, and any one of them could draw in the superpowers.” Because President Ronald Reagan holds impeccable credentials as an unyielding anti-Communist, adds Graham, he has an important opportunity to negotiate arms reductions with the Soviets as a capstone of his administration, “just as Nixon was able to establish relations with the People’s Republic of China.”Graham further is vowing to assail, on moral grounds, the burgeoning federal budget deficit—calling at the same time for a reexamination of the American lifestyle. “We’re going to see this deficit making a tremendous impact on this country’s economy, and it’s going to affect everyone,” he predicts. “We’ve been living way above our means. And this inequity (between the wealthy and the poor within the U.S., and between America and most of the rest of the world) is going to have to change somehow, whether voluntarily or by law. You can’t have some people driving Cadillacs and others driving oxcarts and expect peace in a community. There is a crying need for more social justice.”By the evangelist’s own admission, the U.S. economy, currently under a much-discussed study by the nation’s Roman Catholic bishops, is a vexing and complex problem beyond his understanding. “The solution is beyond me, but I’ve found about 250 verses in the Bible on our responsibility to the poor.”During his crusade in Vancouver, British Columbia, last fall, Graham collected foodstuffs during a “Feed the Hungry” evening meeting to distribute among the poorest residents of that Canadian city. “It was a symbol to preach the message that we want to do something concrete,” he recalls. “We’ve got to have a plan to do this year-round, to help the street people. For most evangelicals, the problem is not motivation, but rather how to do something to help others. They’ve got the gospel—the Cross to transform the heart—and they are finding there are obligations that come with it.”For the past several years, Graham has been stressing with new vigor the themes of self-denial and social responsibility along with his familiar salvation message. “For me, it’s not just accepting Christ as Savior and Lord, but being a Christian every day,” says the evangelist. “I want to emphasize the price you have to pay, and the changes that must occur in your life.”Throughout his ministry, Graham has proclaimed the need for personal and corporate revival, and has long seen glimmers of proof that such changes are in the wind. But today, he says, the entire world is in the throes of a broad and authentic search for transcendent meaning, and the nation is on a religious quest of “major proportions—maybe the greatest of American history.” But the search for the divine “takes many forms,” Graham observes. “They may be turning to a guru somewhere and dabbling in metaphysical philosophy. We have both the false and the true Christianity, side by side—the wheat and the tares. People are hungry for a genuine religious awakening, especially university students. There is a nuclear cloud hanging over these students, and I sense a great fear of war and fear for our future far greater in Europe than in America.”Graham, who has preached in more than 60 countries, has been focusing much of his evangelistic energy in recent years outside the borders of the U.S. He conducted only one American crusade last year (in Anchorage, Alaska), drawing fewer than 10,000 a night; while his appearances in Mexico, Great Britain, South Korea, the Soviet Union, and Canada attracted, in most cases, surprisingly large numbers. This year, in addition to his recently concluded Fort Lauderdale campaign, the evangelist is crusading in Hartford, Connecticut, in May, and Anaheim, California, in July, as well as venturing back to England, Hungary, and Romania.Graham admits that in his youth he “came close to identifying the American way of life with the kingdom of God.” But with his far-flung excursions and his unusual opportunity to observe the Christian church in differing political systems, “then I realized that God had called me to a higher kingdom than America. I have tried to be faithful to my calling as a minister of the gospel.”And the gospel that Graham is now preaching with revitalized determination is a more demanding gospel, stripped of any coating of cheap grace and more subdued in its appeal to the emotions. “I had no real idea that millions of people throughout the world lived on the knife-edge of starvation and … that I have a responsibility toward them,” Graham asserts. “I’ve come to see in deeper ways some of the implications of my faith and the messages I’ve been proclaiming.”It is a gospel rich with the symbols and story of Holy Week, the account of deepest gloom and unspeakable joy, of death and resurrection. It is a message Graham intends to carry to the nations as long as he is given the breath to proclaim it.A related research question touched on universalism, though it asked Christian respondents to assess both “my religion” and “Christian religions.” As researchers described:

There also is wide variance among Christians on the question of whether “many religions” can lead to eternal life in heaven or if their religion is the “one true faith” leading to heaven. Protestants are more than twice as likely as Catholics to say that their faith is the one true faith leading to eternal life in heaven (38% vs. 16%), with half of evangelicals expressing this view. On the other hand, 44% of evangelical Protestants say that many religions can lead to eternal life in heaven, though they are split on whether this reward is granted only to members of other branches of Christianity (19%) or if followers of some non-Christian religions also can go to heaven (23%).

Here is how Americans describe what they believe heaven and hell are like:

Billy Graham discusses hunger, racism, peace, revival, and evangelismThe log house belonging to evangelist Billy Graham sits at the end of a long road slithering up to the crest of Black Mountain. It is a sturdy and warmly appointed place surrounded by thick stands of hardwood and jackpine and blooming mountain laurel. One can hardly imagine, peering through the ethereal haze draping the hills of this North Carolina hamlet, a more idyllic and soulful setting for a retirement home.But for Graham, who now is 66 years old, his all-too-infrequent visits to the family homestead in Montreat provide him only the barest respite from his relentless public and private journeys. As long as he is persuaded the hand of God is upon him, the evangelist says he is dutybound to continue his ministry of preaching throughout the world, adding to the flock of 100 million people who have poured in to his crusades.It has been for him an astonishing and supernatural run as the twentieth century’s most recognized and decorated preacher, confidant to presidents and royalty, and counselor to millions of common folk. But Graham says he will be content with a simple epitaph for his life and ministry: “A sinner saved by grace; a man who, like the psalmist, walked in his integrity. I’d like people to remember that I had integrity.”Still, there is much to do. It is, the evangelist says, “God’s hour for the world,” a time of unprecedented danger and new opportunities, of thunderous approaching hoofbeats and wondrous breakthroughs for the cause of Christianity.He worries that the world stands at the brink of nuclear holocaust. He laments a resurgence of racism and the uneasy peace in South Africa. He wonders about the morality of the distribution of wealth on the globe, and anguishes over the economic disparities in his own homeland. Yet somehow, through it all, he sees signs of hope.He has, in fact, changed in considerable ways since he burst from the halls of Wheaton College in 1943 to take charge of his first pastorate in the nearby Chicago suburb of Western Springs. He became the pastor of the First Baptist Church, a small congregation in a town dominated by parishes of a more mainline stripe. Even then Graham was dropping broad hints that he would not be content with a merely parochial ministry. He was instrumental in changing the name of the congregation to the Village Church in an effort to attract fallen-away Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Methodists who may not have known of the Baptist denomination or who may have harbored a bias against it.Since those early days, Graham has become something of a patriarch for the whole of American Protestantism, admired chiefly by adherents of the more conservative and evangelical faction, but also regarded with growing respect by members of many more liberal denominations. His most persistent detractors, in fact, have been religious extremists largely from the far Right, who fault Graham for his long-standing cooperation with mainline churches that help sponsor his city crusades. More recently, those same critics have charged him with being naïvely soft on communism in the after math of Graham’s widely publicized trips to the Soviet Union and his other forays into Eastern bloc countries.“You can’t help but grow and become more tolerant,” Graham asserts. “Man is really the same the world over, and the gospel is universal in its application. It’s been amazing to me to find believers in every part of the world we’ve been to. There is no force in the world that can destroy Christianity, and history has proven that.”But even as Christianity appears to be advancing in other nations, Graham acknowledges he is dismayed by widening divisions among American Christians and an increasingly sullied image of conservative Protestantism due to the “proliferation” of theologically unsophisticated and often crassly commercial television preachers.“We may be in danger of returning to an Elmer Gantry image as far as evangelism is concerned,” Graham says. “In the 1950s and 1960s, I believe we contributed some to the erasing of that image.” But with the expansion of electronic media ministries in the past decade, and the emphasis by some on “emotion and money,” the cause of Christianity suffers, frets Graham, and all evangelical preachers are viewed with suspicion and often held up to ridicule.“The word ‘evangelical’ is hard to define now” in this new ethos, he says.In addition, the baldly partisan political lobbying in many of America’s churches has exacted a price, Graham says, noting that the toll is one with which he is himself intimately acquainted. “In the political arena, I think there were pastors and evangelists who went too far, both from the Left and from the Right,” in the 1984 national campaigns.Graham, of course, was assailed by many religious leaders for functioning in the role of unofficial White House chaplain through several successive American administrations. For the past decade, Graham has kept a discreet distance from the corridors of power in Washington, D.C., maintaining that even the perception of partisan political activity weakens his credibility as a preacher interested in communicating to people of every ideological tinge and cultural background.Even so, he has become increasingly outspoken on a number of moral issues with political implications, including abortion, multilateral disarmament of nuclear weapons, and the U.S. economic system. And Graham is now pledging to incorporate these controversial questions ever more forcefully into his sermons.“The weapons are getting more dangerous,” he contends, “and I’m more interested in the subject of peace now than I was two or three years ago. I’m not so worried about a war between the United States and the Soviet Union, but I’m thinking of a country like South Africa. If they get their back to the wall, would they use the bomb? What about Pakistan? Or certain countries in the Middle East? They claim that now at least 15 countries have nuclear weapons, and any one of them could draw in the superpowers.” Because President Ronald Reagan holds impeccable credentials as an unyielding anti-Communist, adds Graham, he has an important opportunity to negotiate arms reductions with the Soviets as a capstone of his administration, “just as Nixon was able to establish relations with the People’s Republic of China.”Graham further is vowing to assail, on moral grounds, the burgeoning federal budget deficit—calling at the same time for a reexamination of the American lifestyle. “We’re going to see this deficit making a tremendous impact on this country’s economy, and it’s going to affect everyone,” he predicts. “We’ve been living way above our means. And this inequity (between the wealthy and the poor within the U.S., and between America and most of the rest of the world) is going to have to change somehow, whether voluntarily or by law. You can’t have some people driving Cadillacs and others driving oxcarts and expect peace in a community. There is a crying need for more social justice.”By the evangelist’s own admission, the U.S. economy, currently under a much-discussed study by the nation’s Roman Catholic bishops, is a vexing and complex problem beyond his understanding. “The solution is beyond me, but I’ve found about 250 verses in the Bible on our responsibility to the poor.”During his crusade in Vancouver, British Columbia, last fall, Graham collected foodstuffs during a “Feed the Hungry” evening meeting to distribute among the poorest residents of that Canadian city. “It was a symbol to preach the message that we want to do something concrete,” he recalls. “We’ve got to have a plan to do this year-round, to help the street people. For most evangelicals, the problem is not motivation, but rather how to do something to help others. They’ve got the gospel—the Cross to transform the heart—and they are finding there are obligations that come with it.”For the past several years, Graham has been stressing with new vigor the themes of self-denial and social responsibility along with his familiar salvation message. “For me, it’s not just accepting Christ as Savior and Lord, but being a Christian every day,” says the evangelist. “I want to emphasize the price you have to pay, and the changes that must occur in your life.”Throughout his ministry, Graham has proclaimed the need for personal and corporate revival, and has long seen glimmers of proof that such changes are in the wind. But today, he says, the entire world is in the throes of a broad and authentic search for transcendent meaning, and the nation is on a religious quest of “major proportions—maybe the greatest of American history.” But the search for the divine “takes many forms,” Graham observes. “They may be turning to a guru somewhere and dabbling in metaphysical philosophy. We have both the false and the true Christianity, side by side—the wheat and the tares. People are hungry for a genuine religious awakening, especially university students. There is a nuclear cloud hanging over these students, and I sense a great fear of war and fear for our future far greater in Europe than in America.”Graham, who has preached in more than 60 countries, has been focusing much of his evangelistic energy in recent years outside the borders of the U.S. He conducted only one American crusade last year (in Anchorage, Alaska), drawing fewer than 10,000 a night; while his appearances in Mexico, Great Britain, South Korea, the Soviet Union, and Canada attracted, in most cases, surprisingly large numbers. This year, in addition to his recently concluded Fort Lauderdale campaign, the evangelist is crusading in Hartford, Connecticut, in May, and Anaheim, California, in July, as well as venturing back to England, Hungary, and Romania.Graham admits that in his youth he “came close to identifying the American way of life with the kingdom of God.” But with his far-flung excursions and his unusual opportunity to observe the Christian church in differing political systems, “then I realized that God had called me to a higher kingdom than America. I have tried to be faithful to my calling as a minister of the gospel.”And the gospel that Graham is now preaching with revitalized determination is a more demanding gospel, stripped of any coating of cheap grace and more subdued in its appeal to the emotions. “I had no real idea that millions of people throughout the world lived on the knife-edge of starvation and … that I have a responsibility toward them,” Graham asserts. “I’ve come to see in deeper ways some of the implications of my faith and the messages I’ve been proclaiming.”It is a gospel rich with the symbols and story of Holy Week, the account of deepest gloom and unspeakable joy, of death and resurrection. It is a message Graham intends to carry to the nations as long as he is given the breath to proclaim it.