Sorry Job, Epicurus, Augustine, and Hume: On the “problem of evil,” most Americans don’t think much of God’s role.

Long before Rabbi Harold Kushner’s When Bad Things Happen to Good People got Americans talking about theodicy in the 1980s, these famous thinkers wrestled with explaining why an all-loving, all-knowing, and all-powerful God would allow suffering.

Amid the pandemic and its 5.2 million reported deaths, the Pew Research Center surveyed 6,485 American adults—including 1,421 evangelicals—in September 2021 about how they philosophically “make sense of suffering and bad things happening to people.”

The most common explanation: It happens.

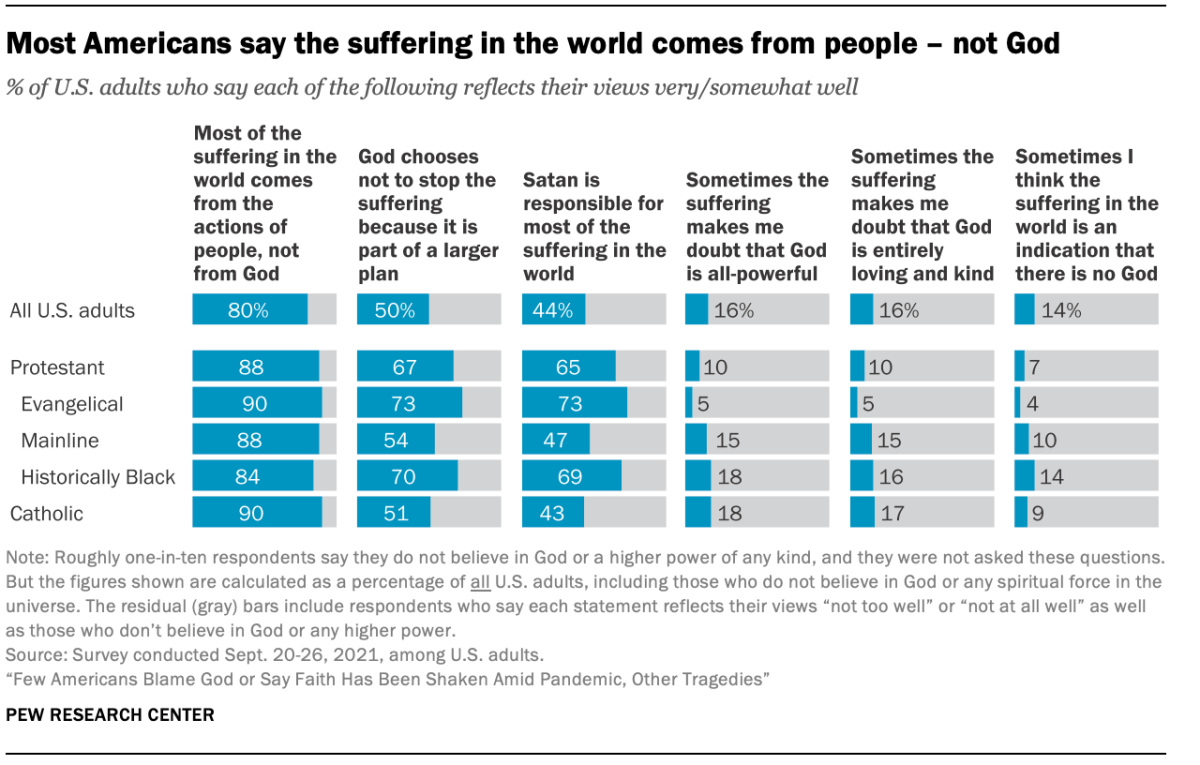

“Americans largely blame random chance—along with people’s own actions and the way society is structured—for human suffering, while relatively few believers blame God or voice doubts about the existence of God for this reason,” concluded Pew researchers in a new study released today.

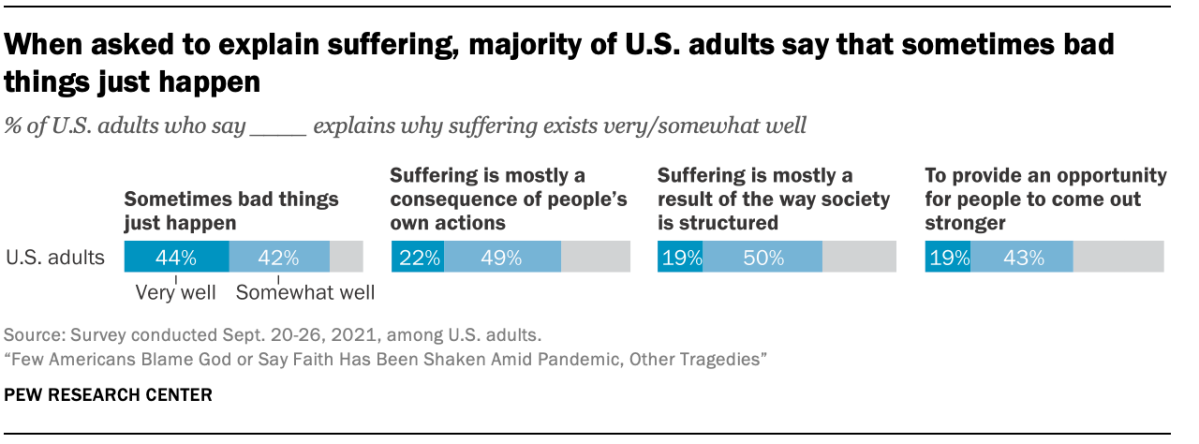

Yet many Americans do see purpose in pain, as researchers noted:

The vast majority of U.S. adults ascribe suffering at least partly to random chance, saying that the phrase “sometimes bad things just happen” describes their views either very well (44%) or somewhat well (42%). Yet it is also quite common for Americans to feel that suffering does not happen in vain. More than half of U.S. adults (61%) think that suffering exists “to provide an opportunity for people to come out stronger.” And, in a separate set of questions about various religious or spiritual beliefs, two-thirds of Americans (68%) say that “everything in life happens for a reason.”

How we can give up our preoccupation with the puny objects of ourselves.

How we can give up our preoccupation with the puny objects of ourselves.“Each citizen is habitually engaged in the contemplation of a very puny object, namely himself.”

—Alexis de TocquevilleIn the century and a half since de Tocqueville penned those words about the American experience, little has changed. No one, and no thing, interrupts people more than momentarily from their obsessive preoccupation with themselves. Indeed, concerned observers using the diagnostic disciplines of psychology, sociology, economics, and theology lay the blame for the deterioration of our public and personal lives at the door of the self.It seems America is still in conspicuous need of unselfing.Of course, a few people carry placards to try to wake up the masses to the danger in which a century of mindless selfishness has put us. Desperately they try to avert the destruction of the Earth by protesting the insanities of militarism, the greedy and reckless practices ravaging our streams, forests, and air, and the bloated consumerism leaving much of the world hungry and poor.Others hand out tracts in an attempt to startle the shuffling crowds into dealing with their souls, not just their selves. They urgently call attention to the eternal value of the soul, present the authoritative words of Scripture, and ask the big question, “Are you saved?”Both groups attract occasional flurries of attention, but not for long. And while both groups care, they do not seem to care much for each other. One group wants to save society, the other to save souls. Neither recognizes a common ground.From time to time other solutions are offered: psychologists propose a therapy, educators install a new curriculum, economists plan legislation, sociologists imagine new models for community. Think tanks hum. Ideas proliferate. Some of them get tried. Nothing seems to work for very long.In Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s now famous sermon to America, delivered in 1978 at Harvard University, he said, “We have placed too much hope in politics and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life. It is trampled by the party mob in the East, by the commercial one in the West.” We are, he thundered, at a “harsh spiritual crisis and a political impasse. All the celebrated technological achievements of progress, including the conquest of outer space, do not redeem the twentieth century’s moral poverty.” We need a “spiritual blaze.”What the journalists did not report (not a single pundit so much as mentioned it) is that a significant number of people are actually doing something about Solzhenitsyn’s concern. I work with some of these people, encouraging and sometimes providing guidance. Thousands of pastors, priests, and lay colleagues are similarly engaged. They are doing far more for both society and the soul, tending and fueling the “spiritual blaze,” than anything that is being reported in the newspapers. The work is prayer.The Unselfing: Its Power SourcePrayer, of course, has to do with God. God is both initiator and recipient of this underreported but extensively pursued activity. But prayer also has to do with much else: war and government, poverty and sentimentality, politics and economics, work and marriage. Everything, in fact. The striking diagnostic consensus of modern experts that we have a self problem is matched by an equally striking consensus among our wise ancestors of a strategy for action: the only way to escape from self-annihilating and society-destroying egotism and into self-enhancing community is through prayer.Only in prayer can we escape the distortions and constrictions of the self and enter the truth and expansiveness of God. And we find there, to our surprise, both self and society whole and blessed. It is the old business of losing your life to save it; and the life that is saved is not only your own, but everyone else’s as well.Prayer is political action. Prayer is social energy. Prayer is public good. Far more of our nation’s life is shaped by prayer than is formed by legislation. That we have not collapsed into anarchy is due more to prayer than to the police. Prayer is a sustained and intricate act of patriotism in the largest sense of that word—far more precise, loving, and preserving than any patriotism served up in slogans. That society continues to be livable and that hope continues to be resurgent are attributable to prayer far more than to business prosperity or a flourishing of the arts. The single most important action contributing to whatever health and strength there is in our land is prayer. It is not the only thing, of course, for God uses all things to effect his sovereign will. But prayer is, all the same, the source action.Now, the single most widespread American misunderstanding regarding prayer is that it is private. Yet strictly and biblically speaking, there is no such thing as private prayer. Private, in its root meaning, refers to theft. It is stealing. When we privatize prayer we embezzle the common currency that belongs to us all. When we engage in prayer without any desire for, or awareness of, the comprehensive, inclusive life of the kingdom that is “at hand,” we impoverish the social reality that God is bringing to completion.Solitude in prayer is not privacy. And the differences between privacy and solitude are profound. Privacy is our attempt to insulate the self from interference; solitude leaves the company of others for a time in order to listen to them more deeply. Privacy is getting away from others so we don’t have to be bothered with them; solitude is getting away from the crowd so we can be instructed by the still, small voice of God. Private prayers are selfish and thin; prayer in solitude enrolls in a multi-voiced, century-layered community.We can no more have a private prayer than we can have a private language. Every word spoken carries with it a long history of development in complex communities of experience. All speech is relational, making a community of speakers and listeners. So, too, is prayer. Prayer is language used in the vast contextual awareness that God speaks and listens. We are involved, whether we will it or not, in a community of the Word—spoken and read, understood and obeyed (or misunderstood and disobeyed). We can do this in solitude, but we cannot do it in private. It involves an Other and others.The self is only itself, healthy and whole, when it is in relationship. And the healthy relationship is always dual, with God and with other human beings. Relationship implies mutuality, give and take, listening and responding. If the self exploits other selves, whether God or neighbor, subordinating them to its compulsions, it becomes pinched and twisted. If the self abdicates creativity and interaction with other selves, whether God or neighbor, it becomes flaccid and bloated. Neither by taking charge or by letting others take charge is the self itself. It is only itself in relationship.But how do we develop that relational sense? How do we overcome our piratical rapaciousness on the one hand and our parasitic sloth on the other? How do we develop not only as Christians but as citizens? How else but in prayer? Many things—ideas, persons, projects, plans, books, committees—help and assist. But the “one thing needful” is prayer.The Unselfing: Its PatternThe best school for prayer continues to be in the Psalms. It also turns out to be an immersion in politics. In the Psalms, the people who teach us to pray were remarkably well integrated in these matters. No people have valued and cultivated the sense of the person so well. At the same time, no people have had a richer understanding of themselves as a “nation under God.” They prayed when they were together and they prayed when they were alone—and it was the same prayer in either setting. Prayer was their characteristic society-shaping and soul-nurturing act. These prayers, these psalms, are terrifically personal and at the same time ardently political.The word politics, in common usage, means “what politicians do” in matters of government and public affairs. The word often carries undertones of displeasure and disapproval because the field offers wide scope for the misuse of power over others. But the word cannot be abandoned just because it is dirtied.It derives from the Greek word polis (city). It represents everything that people do as they live with some intention in community, as they work toward some common purpose, as they carry out responsibilities for the way society develops. Biblically, it is the setting in which God’s work with everything and everyone comes to completion (Rev. 21). He began his work with a couple in a garden; he completes it with vast multitudes in a city.For Christians, “political” acquires extensive biblical associations and dimensions. Rather than look for another word untainted by corruption and evil, it is important to use it as it is in order to train ourselves to see God in those places that seem intransigent to grace. It is both unbiblical and unreal to divide life into the activities of religion and politics, or into the realms of sacred and profane. The question is how to get these activities or realms together without putting one into the unscrupulous hands of the other?Prayer is the answer. Prayer is the only means adequate for the great end of getting these polarities in dynamic relation—for making politics become religious and religion become political. And the Psalms are our most extensive source documents showing us how this can be done.The Psalms are an edited Book: 150 prayers collected and arranged to guide and shape our responses to God accurately, deeply, and comprehensively. Everything that is possible to feel and experience in relation to God’s creative and redeeming word in us is voiced in these prayers. (John Calvin called the Psalms “an anatomy of all the parts of the soul.”)Two psalms are carefully set as an introduction: Psalm 1 is a laser concentration of the person; Psalm 2 is a wide-angle lens on politics. God deals with us personally, but at the same time he has public ways that intersect the lives of nations, rulers, kings, and governments. The two psalms are by design a binocular introduction to the life of prayer, an initiation into the responses that we make to the Word of God personally (“blessed is the man,”1:1) and politically (“blessed are all,”2:11).Psalm 1 presents the person who delights in meditating on the law of God; Psalm 2 presents the government that God uses to deal with the conspiratorial plots of peoples against his rule. All the psalms that follow range between these introductory poles, evidence that there can be no division in the life of faith between the personal and the public, between self and society.Contemporary American life, though, shows great gulfs at just these junctures. And at least one reason is that we love Psalm 1 and ignore Psalm 2. It seems to me strategically important to reintroduce this psalmic mix as source prayers for the “unselfing of America.” Praying them, or after their manner, breaks through the barrier of the ego and into the kingdom that Christ is establishing.We often imagine, wrongly, that the Psalms are private compositions prayed by a shepherd, traveler, or fugitive. Close study shows that all of them are corporate: all were prayed by and in the community. If they were composed in solitude, they were prayed in the congregation; if they originated in the congregation, they were continued in solitude. But there were not two kinds of prayer, public and private. It goes against the whole spirit of the Psalms to take these communal laments, these congregational praises, these corporate intercessions, and use them as cozy formulas for private solace.God does not save us so we can cultivate private ecstasies. He does not save us so we can be guaranteed a reservation in a heavenly mansion. We are made citizens in a kingdom—that is, a society. He teaches us the language of the kingdom by providing the Psalms, which turn out to be as concerned with rough-and-tumble politics as they are the quiet waters of piety. So why do we easily imagine God tenderly watching over a falling sparrow but boggle at believing that he is present in the hugger mugger of smoke-filled rooms?In a time when our sense of nation and community is distorted, when so many Christians have reduced prayer to a private act, and when so many others bandy it about in political slogans, it is essential that we recover the kingdom dimensions of prayer. For many, recovery begins in attending to the ancient and widespread work of unselfing evident in the Psalms. We move from there to encouragement in the use of the psalm-prayers for the commonweal.The Unselfing: Its ImpactThis unselfing is taking place all across the land. Bands of people meet together regularly to engage in the work. Disbanded, they continue what they began in common. They are persistent, determined, effective. “The truly real,” Karl Jaspers noted, “takes place almost unnoticed, and is, to begin with, lonely and dispersed.… Those among our young people who, thirty years hence, will do the things that matter, are, in all probability, now quietly biding their time; and yet, unseen by others, they are already establishing their existences by means of an unrestricted spiritual discipline.”Assembled in acts of worship, they pray. Dispersed, they infiltrate homes, shops, factories, offices, athletic fields, town halls, courts, prisons, streets, play grounds, and shopping malls, where they also pray. Much of the population, profoundly ignorant of the forces that hold their lives together, does not even know that these people exist.These people who pray know what most around them either do not know or choose to ignore: Centering life in the insatiable demands of the ego is the sure path to doom. They know that life confined to the self is a prison—a joy-killing, neurosis-producing, disease-fomenting prison. Out of a sheer sense of survival they are committed to a way of life that is unselfed, both personally and nationally. They are, in the words of their Master, “light” and “leaven.” Light is silent and leaven is invisible. Their presence is unobtrusive, but these lives are God’s way of illuminating and preserving civilization. Their prayers counter the strong disintegrative forces in American life.We don’t need a new movement to save America. The old movement is holding its own and making its way very well. The idea that extraordinary times justify extraordinary measures is false and destructive counsel. We don’t need a new campaign, a new consciousness raising, a new program, new legislation, new politics, or a new reformation. The people who meet in worship and offer themselves in acts of prayer are doing what needs to be done.Moreover, their acts of prayer are not restricted to what they do on their knees or at worship. Even as the prayers move into society, they move us into society. There is no accounting for exactly where we end up: some are highly visible in political movements while others work obscurely and unnoticed in unlikely places. We learn to be obedient to what the Spirit is doing in us and not to envy or criticize those whose obedience carries them down different paths. Sometimes what others do looks like disobedience; sometimes they appear to abandon the passion for prayer in the passion for action. But the faithful who continue at prayer enfold the others and sustain them in the petition, “Deliver us from evil.”These citizens have unmasked the Devil’s deception that prayer is a devotional exercise in which pious people engage when they are cultivating some private felicity with the Almighty or to which profane people are reduced in desperate circumstances. They have recognized the deep, embracing, reforming, revolutionizing character of prayer: It is essential work in shaping society and in forming the soul. It necessarily involves the individual, but it never begins with the individual and it never ends with the individual.We are born into community, we are sustained in community: our words and actions, our being and becoming either diminish or enhance the community just as the community either diminishes or enhances us. Prayer acts on the principle of the fulcrum, the small point where great leverage is exercised—awareness and intensification, expansion and deepening at the conjunction of heaven and earth, God and neighbor, self and society. Prayer is the action that integrates the inside and outside of life, that correlates the personal and the public, that addresses individual needs and national interest. No one thing we do is simultaneously more beneficial to society and soul as the act of prayer.The motives of those who pray are both personal and public, ranging from heaven to earth and back again. They pray out of self-preservation, having been told on good authority that only the one who loses his life will save it. They also pray as an act of patriotism, knowing that life is so delicately interdependent that every act of pollution, each miscarriage of justice, any capricious cruelty—even when occurring halfway across the country or halfway around the globe—diminishes the person who is not immediately hurt as much as the person who is.Prayer is a repair and a healing of the interconnections. It drives to the source of the divisions between the holy and the world—the ungodded self—and pursues healing to its end, settling for nothing less than the promised new heaven and new earth. “Our citizenship is in heaven,” say those who pray, and they are ardent in pursuing its prizes. But this passion for the unseen in no way detracts from their involvement in daily affairs: working well and playing fair, signing petitions and paying taxes, rebuking the wicked and encouraging the righteous, getting wet in the rain and smelling the flowers.Theirs is a tremendous, kaleidoscopic assemblage of bits and pieces of touched, smelled, seen, and tasted reality that is received and offered in acts of prayer. They obey the dominical command, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s.”

Among the survey’s main findings:

- 7 in 10 American adults agree that suffering is “mostly a consequence of people’s own actions.” Yet also 7 in 10 agree that suffering is “mostly a result of the way society is structured.”

- 8 in 10 are believers—either in “God as described in the Bible” (58%) or in “a higher power or spiritual force” (32%)—yet say most suffering “comes from the actions of people, not from God.”

- 7 in 10 believe human beings are “free to act in ways that go against the plans of God or a higher power.”

- 5 in 10 believe God allows suffering because it is “part of a larger plan.”

- 4 in 10 believe Satan is responsible for most of the world’s suffering.

- Less than 2 in 10 say they have doubted God’s omnipotence, goodness, or existence because of suffering.

As mentioned in the preface of last month’s article by Barbara Thompson on the Bruderhof, which focused on that community’s understanding of the place of the Christian within the nation, the initial presentation of the Christianity Today Institute will address the subject of “The Christian As Citizen.” Featuring the insights of evangelical scholars and practitioners, this special institute supplement will appear in the April 19 issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY.

As mentioned in the preface of last month’s article by Barbara Thompson on the Bruderhof, which focused on that community’s understanding of the place of the Christian within the nation, the initial presentation of the Christianity Today Institute will address the subject of “The Christian As Citizen.” Featuring the insights of evangelical scholars and practitioners, this special institute supplement will appear in the April 19 issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY.In anticipation, the following article by Stephen Monsma, who was himself a participant in the first meeting of the institute, deals with the relationship between faith and political decision making, politics and government, from a Reformed perspective.

“Dirty politics” is a phrase that is almost as common as “Merry Christmas.” In fact, we have a whole stable full of terms with negative connotations that we often use to describe political phenomena: “smoke-filled rooms” instead of “conference rooms,” “political hacks” instead of “political organizers.”

From my own experience as a legislator in both the Michigan State House and Senate, I can testify that the political process is often seamy and even sordid.

The problem is that the system, with its interlocking network of attitudes and expectations that permeate our political institutions and practices, creates an atmosphere where such ideals as justice, righteousness, order, and servanthood are absent. Thus those who struggle for these ideals do not face their biggest challenge from some particularly dramatic, clearly labeled evil, but from nebulous, all-pervasive attitudes and expectations. Evil is everywhere and nowhere. It is everywhere in that it is pervasive and ever-present; it is nowhere in that it can come to appear so natural and so much a part of the political atmosphere that it goes unnoticed, like the air we breathe. The God-inspired political struggle for greater justice thereby becomes a spiritual struggle against “the powers of this dark world,” against seemingly all-powerful, intractable forces, forces of parochial self-interest, ponderous inertia, and organized special interests.

Christians are called to redeem politics in the name of Jesus Christ, empowered to transform, not to be conformed to the world of politics as it is.

There are five basic characteristics of the political process, often misunderstood and always open to abuse. To redeem politics successfully, we need to consider politics as combat, as compromise, as teamwork, as public relations, and as representation.

Politics As Combat

Political decisions are decisions that deeply affect the lives and values of people and groups in society—as when a government contract is gained or lost and employment or unemployment results, or a toxic-waste dump is or is not built in one’s neighborhood.

Because vitally important decisions are made in the face of sharply divergent views, struggle or combat results. And because the stakes are often very high in politics, people regularly risk health, financial security, and family in order to pursue political goals. The Watergate scandal vividly demonstrated the lengths to which people will go for persons and causes they believe in.

In its unredeemed state, the combativeness of politics can easily degenerate into a struggle dominated by people’s selfish ambitions and marked by nothing more substantive than macho swagger. The political world is largely male, dominated by people whose primary goals are all too often getting reelected, amassing greater personal power, and commanding the ego-satisfying deference that comes with political power.

If a person is not clearly and self-consciously committed to pursuing his or her vision of a just order, a truly good society, it is almost inevitable that this person will soon be wallowing in the mire of selfish ambition, using the issues and the needs of society to help assure his political survival and build his political power.

But when politics has been brought under the lordship of Jesus Christ, one’s political struggles are focused and directed by one’s tenacious drive for a more just order. It is a struggle—often an exhausting, frustrating, debilitating struggle—but one with a goal firmly rooted in moving society toward greater justice. In the process one becomes a servant of those suffering injustice.

This does not mean that one should squander all political influence pursuing clearly unattainable goals (although at times our Lord may call us to do exactly that). We are called to be wise, perhaps even wily, not for the purpose of advancing ourselves, not to gain more power for power’s sake, but to advance God’s cause of greater justice in society. This is the essence of political servanthood.

Politics As Compromise

A second basic characteristic of politics is compromise. It plays a crucial role in politics because it is the means by which differing individuals or groups are able to resolve their differences and reach agreement.

For Christians, who have been taught to struggle for the clear, absolute truth of the Bible, the very word “compromise” has a somewhat unsavory ring to it. In a struggle of justice against injustice, is not any compromise an unacceptable accommodation to evil? I would say no. I can easily picture certain conditions where a compromise would be completely compatible with redeemed politics. In fact, it can be argued that politics based on negotiated compromises is often preferred.

One must not picture the political arena as involving the struggle of absolute good versus absolute evil, of total justice versus total injustice. The real world is never that simple. Typically, even the Christian politician pursuing justice in a sinful world feels caught in a dense fog. He or she has a fairly good sense of justice and what it means on the contemporary scene. But the questions public officials face come in specific, concrete, often technical forms. In such situations—with important information missing and values clashing—even the Christian public official has only a partial idea of what is needed. And then he or she may be mistaken.

Sometimes Christians enter the political arena with a very rigid, explicit vision of what they believe needs to be accomplished. And they pursue that vision with a self-confidence that becomes arrogance. This is wrong. One mark of Christians in politics should be a sensitivity to their own limitations and fallibility. God’s Word is truth. The principle of justice is absolute. But our applications of God’s truth and of his standard of justice are often fumbling and shrouded in the fog produced by extremely complex situations, missing information, and the pressures of limited time.

What does all this have to do with compromise? Simply this: When one is asked to compromise, one is not being asked to compromise absolute principles of right and wrong. Instead, one is being asked to compromise on groping, uncertain applications of basic biblical principles. There is a big difference.

As a state senator, I was the sponsor of drunk-driving reform legislation in Michigan. In order to get the bills through the Senate, I had to take out one of the key provisions: allowing the police to set up checkpoints at random and to give every driver passing by a sobriety test. Then in the House Judiciary Committee I had to give up mandatory prison terms for convicted drunk drivers—even for drunk drivers who had killed another person. But much was left in the bills, including long-term, mandatory revocation of the licenses of convicted drunk drivers and stronger enforcement tools for the police and prosecutors. Some criticized me for giving away too much, but I defended what I did on two grounds. One was that if I had held firm I probably would not have gotten any bills passed at all. I was operating according to the “half a loaf is better than none” philosophy, and I believe it is appropriate. One pushes constantly, insistently, for more just politics, but progress comes step by step instead of in one fell swoop. As soon as one step is taken, one begins exerting pressure for the next. No bill, no action is seen as the end of the matter. One grabs as much justice as one can today, and comes back for more tomorrow.

But I also justify this approach on a second ground: this step-by-step evolution of policies is less likely to lead to unanticipated, negative consequences. That quantum leap into the future that I may think will usher in the ultimate in justice may, if I could attain it, prove to be a disaster—or at least much less than the vision of true justice I had in mind. Thus the more cautious step-by-step approach that the realities of politics usually force us to take is really not all bad. There is something to be said for giving the police some additional tools with which to deal with drunk drivers, assessing their effectiveness, and then deciding whether or not sobriety checkpoints and mandatory prison terms are also needed. The more guarded approach I was forced to take has its good points.

The compromising nature of politics gets one into trouble when one is really not concerned with issues at all but is only interested in his or her selfish ambitions. Then a person will be willing to compromise as long as another bill is passed to his or her credit.

Under such circumstances compromise is used not to push for as much justice as one can get at that time but to satisfy one’s own selfish desires. Justice is displaced by personal ambition and pride.

In summary, negotiated compromise is a frequent outcome of political combat. In its redeemed form, politics as compromise works insistently, persistently, for increased justice in a step-by-step fashion, recognizing that some progress toward greater justice is better than none at all, and that small, incremental steps toward justice may be a wiser stride than giant quantum leaps, which run the danger of going down false paths. But in its unredeemed form, compromise is used to give the illusion of progress or change merely to build up one’s reputation and to feed one’s selfish ambitions.

Politics As Teamwork

A third basic characteristic of politics is teamwork. Working for greater justice through political action is not an individual enterprise but a joint or group process. Almost any political project one can undertake involves building a coalition among like-minded individuals and groups.

Saying this much appears to be stating the obvious. Yet many of the most difficult moral dilemmas and, I suspect, much of the unsavory reputation of politics arise from this very characteristic. The danger is that in allying oneself with certain individuals and groups one will incur debts that will compromise one’s basic independence and integrity.

All elected officials have a coalition of support groups to whom they turn for campaign funds and volunteers and for help in getting legislation passed. They will vary greatly depending on the background, political philosophy, and partisanship of the individual, but all elected officials are backed by certain coalitions or “terms.”

But this relationship between public official and supporting coalition cannot be simply a one-way street. One cannot expect individuals and groups to be at one’s beck and call, ready and eager to offer support and help, without them, in turn, having a say about what one is doing. Sometimes even the conscientious, justice-oriented official votes or acts differently or alters the strategies he or she pursues out of deference to one or more groups or individuals.

The Right-to-Life organization is one group that I have worked with very closely throughout my political career. It is part of my coalition or team. Once this relationship resulted in my leading the struggle in the senate for a bill to forbid the spending of tax money to pay for Medicaid abortions, even though I would have preferred to accomplish this by other means. I thought we should have tried to discharge the committee that had bottled up this legislation. But the majority leader of the senate opposed this, and the consensus of the Right-to-Life leadership was to insert the desired language in another bill that was in another committee more favorable to our position. The only problem was that doing so probably violated senate rules, and one could question whether the new language was germane to the intent of the original bill. We had the votes, so we pushed the new language through by overturning a ruling of irrelevancy by the lieutenant governor. I ended up in the uncomfortable position of having to argue on the floor of the senate and to the news media that something was germane when I and everyone else knew it probably should not be considered germane according to past senate decisions. Yet I did so, and I still believe I did the right thing, because the team that I had joined, the coalition that I was a part of, had jointly decided that this was the way to go. A politician is not a prima donna but a player in an orchestra.

There are, I believe, two key requirements that a politician must meet to avoid slipping into practicing unredeemed politics, to be able to transform the team aspect of political activity. First of all, the individuals and groups with which one allies oneself must be those whose basic principles and basic orientations on issues are in keeping with the promotion of a more just order. Politicians guided by selfish ambition will select teams or coalitions that will add most to their clout, those with money, prestige, and connections.

A second requirement is that one must place strict limits on the extent to which one will modify one’s positions or tactics to accommodate a group decision. In the situation described earlier, I was willing to fight for a germaneness ruling that was probably not in keeping with senate rules and precedent. But I would not have been willing to fight for a ruling that would be contrary to the state constitution or basic justice.

Yet those who practice unredeemed politics put such a strong emphasis on their personal ambitions that they would not risk losing a key person or groups of their coalition by refusing to go along, even if they disagreed with the position on a crucial, fundamental issue. They are no longer team members, parts of coalitions; they are prostitutes. They have sold themselves to their supporters.

In summary, politics means teamwork, and teamwork means working with others and even modifying one’s own positions to maintain the unity of one’s team. But in its unredeemed form this is done only with an eye to enhancing one’s own selfish ambitions. If it is to be redeemed, political teamwork must occur in the context of shared fundamental ideals and within reasonable boundaries.

Politics As Public Relations

Anyone in politics is under constant pressure to please and to look good to the public, to key individuals and groups, and to the news media. This is important for reelection. But it is also important for less obvious but equally significant reasons. Life is easier and political influence is greater when one is very popular. Psychologically, we all need the reassurance that we are okay, that we are good people doing a good job, and we all cringe when we are ridiculed or criticized. Politicians are certainly no exception.

Thus, politically active people are sensitive about their public relations. They strive not only to do a good job but to ensure that the general public, the news media, and their friends and supporters realize what kind of job they are doing.

In its unredeemed form this characteristic of politics can turn politics into nothing more than one big con game. Politics often takes place on two quite separate tracks. One track is the world governed by people’s values, the realities of the world as it is, powerful interest groups, and powerful political figures. The other track is the world of appearances, of public profiles and rhetoric. Very often the two are quite different.

Typically, the worst time for these sorts of flimflam games is during election campaigns. Often the operating procedure seems to be, “Say whatever will get you a few more votes. No one will notice whether or not what you are saying back home squares with the way you vote in Washington or the state capitol.”

I am convinced that politics does not have to operate on this sort of two-track system, that it does not have to be a big con game. But it takes the transforming power of Jesus Christ to say no to this kind of politics.

Working to maintain good public relations can be a proper characteristic of politics. The political struggle in a democracy is and should be waged in the glare of publicity. This means that even Christian politicians must be concerned about their public relations, about their images, and how people and the news media are perceiving their actions. But the Christian politician, it he or she is to be faithful to the Lord, must ensure that public appearances are an accurate reflection of what he or she really is and is really doing. Honesty is the key term here. That must be the inviolable standard. Nothing less will do.

But one cannot assume that simply doing right will automatically ensure that the public will perceive one favorably. Two factors are involved here. First, one has to communicate to the public who one is and what one stands for. It is easy for a politician to cause the public to think an opponent is someone he or she is not. At various times in my political career I have been accused of being soft on crime, being in league with the pornography industry, accepting illegal campaign contributions, and being opposed to nonpublic Christian schools. All of these charges are false, but unless one has some means to respond to such charges or has built up quite a different image, one could soon become the victim of such charges.

A second factor is that one is periodically in a situation where he or she will have to take an unpopular stance. Through good public relations one can build up capital, minimize criticisms, and stress the positive advantages of the stance.

In summary, politics as public relations grows out of the open public nature of the political process. In its unredeemed form, politics as public relations degenerates into a big con game marked by attempts to deceive the public into seeing one’s actions as something other than what they really are. In its redeemed state, politics as public relations accurately reflects who one is and what one is doing, but does so in such a way that one’s public image is improved.

Politics As Representation

The United States is ruled by a representative form of government. The members of Congress’s lower house are called representatives. Presumably they represent not themselves, not their own ideas of right and wrong, but the people who have elected them.

This concept of governing creates a problem, perhaps even a dilemma. What happens when a majority of the people who elected a representative are clearly in favor of an unjust policy? One is supposed to represent them—this is a cornerstone of the system of democratic government. Yet one entered politics in order to pursue justice. Is this to be sacrificed when 51 percent of one’s constituents take an opposite position? Presumably not. But if one does not do so, has not he or she supplanted democracy with an elitism that assumes that the politician knows better than the people who elected him or her?

Before suggesting an answer, I should point out a crucial factor. The dilemma of the previous paragraph made three assumptions, all of which are false: that all people have opinions on key public-policy issues, that those opinions are known to public policymakers, and that the intensity with which people hold an opinion and the knowledge on which they base it ought not to affect the policymaker.

In fact, on most public-policy issues a majority of the public will have either no opinion at all or a lightly held, ever-shifting opinion. Public opinion polls have found that on issues that have not been dominating the news for months, slight differences of wording in the questions can result in big differences in the public’s responses. What does representing the public mean in situations like this?

To add to the difficulty, one can never be certain what the state of opinions back home are on any given issue. Legislators receive letters from their constituents. They meet frequently with constituent groups, and their friends feel free to give their opinions. There are periodic public opinion polls. But almost invariably they encompass larger areas than one’s legislative district. The result is a fuzzy notion of what people back home are thinking. But add this to the shifting, uncertain nature of public opinions themselves, and even the representative determined to reflect accurately whatever the hometown public is thinking is usually left in a thick fog.

Still more confusing is the factor of intensity. Suppose 60 percent of the people (we will assume perfect knowledge about the percentage) favor one side of an issue, but do not have much knowledge or strong feelings about it. And 20 percent know the issue well and take very strong opposite positions. But the other 20 percent of the public has no opinion at all. Should the legislator who is trying faithfully to reflect the public’s feelings side with the marginally committed 60 percent or the intensely committed 20 percent? Abstract theories of representation have no answer. Ought not both the strength of one’s opinion and the amount of knowledge on which it is based count for something? The 20 percent, because of the strength of their beliefs, are probably writing many more letters, meeting with their representatives, and in other ways expressing their opinions, while the 60 percent are largely sitting back, uninvolved.

This in fact is precisely the situation that exists in regard to gun-control legislation. Public opinion polls regularly show a clear majority of Americans in favor of stricter gun-control legislation. But the minority that is opposed to further gun control believes in its position much more strongly and is much more willing to act on its beliefs than is the majority that favors stricter gun controls. If I were seeking merely to reflect the opinions of the people I represent, should I be for or against further gun control?

Given this muddled picture, let us turn to the meaning of politics as representation.

In its unredeemed form, politics as representation asks how one can use or manipulate public opinions to maximize one’s chances of election or reelection and to increase one’s political power. Thus, one will naturally avoid going against strongly held public opinions. Intensity becomes the key factor. Only people who feel intensely about an issue are likely to vote for or against a legislator and are likely to write a nasty letter to the editorial column of the local newspaper if the legislator takes the “wrong” position. Special weight will also be given to the opinions of past or potential campaign contributors or powerful people in the community.

What must also be factored is potential intensity. An issue may be attracting very little attention, but if it can be used by an opponent in the next election to make one look bad in the eyes of many voters, the person guided by selfish ambitions will be very concerned.

Thus, in unredeemed politics, the politician is constantly on the alert to use issues to build support or avoid losses and justify these actions on the basis of representing the people. But the principal motivation here is really a selfish desire to strengthen or solidify one’s political base.

In redeemed politics one follows one’s conception of justice, not the leanings of public opinions. If necessary, one should go against the wishes of that majority and support the side of justice. To do otherwise would negate the entire point of having a justice-oriented Christian in public office. Each vote and each position a justice-oriented legislator takes should be saying, “This is what I believe is right and just,” not “This is what I believe most people in my district are in favor of.”

But more needs to be said. The Christian legislator can easily fall victim to an arrogant elitism in which the prevailing attitude is, “Look, I know what’s best for you. So you just be quiet and accept what I know is right. After all, I’m following biblical justice.” Such an attitude is wrong and would set redeemed, justice-oriented politics at odds with democratic politics.

There needs to be a strong sense of Christian humility based on an understanding of one’s own fallibility and limited knowledge. The Christian legislator should vote according to his or her own convictions of justice, but he must first ask himself, “What am I missing that so many others are seeing?”

There is an old Indian proverb that one should not criticize another until one has walked in the other’s moccasins. Similarly, policymakers who are true servants of those whom they represent will act only after walking and talking open-mindedly with those for whom they are making decisions. Sometimes doing so will make them change their minds. When policymakers take this servantlike attitude, justice-oriented politics is saved from degenerating into an arrogant, elitist politics. True representation still exists.

However, the representation process should not be a simple one-way street. Constitutents can often help educate and broaden the perspective and knowledge of their representative, but the representative can do the same for those whom he or she represents. In redeemed politics the representation process is a creative, two-way street. Through personal meetings, telephone conversations, responses to letters, and statements to the media, legislators are able to share with their constituents what they have learned in Washington or at the state capitol. The public tends to be narrow in perspective. The legislator, on the other hand, is forced to view things from a much broader perspective, and thus has a responsibility to share that perspective with his or her constituents. A valuable two-way communications system is thereby created.

Politics as representation is important. Christian, justice-oriented public officials are representatives. But this does not mean that they slavishly follow the shifts in public opinion, nor that they pacify people with strong opinions, only to head off possible adverse public reactions, and that to protect their selfish political interests. Instead, Christian public officials redeem the political process by pursuing justice, while taking time to dialogue with those whom they represent, willing both to lead and to be led by them.

Politics that is enslaved to the powers of this dark world and politics that has been redeemed by Jesus Christ differ widely because they follow two entirely different standards. The politics of this world is based on selfish ambitions—getting ahead, building one’s political power, expanding one’s base. The politics of our Lord is based on servanthood and justice. Justice is the goal. Subordinating personal needs and desires to pursue that goal, one becomes a servant.

While members of evangelical and historically black Protestant churches are nearly equal in their views that God has a larger plan for suffering (73% vs. 70%) and of Satan’s responsibility for suffering (73% vs. 69%), black Protestants were three times as likely as evangelicals to say suffering makes them doubt that God is all-powerful (18% vs. 5%), doubt that God is all-loving (16% vs. 5%), or doubt that God exists (14% vs. 4%). The views of mainline Protestants and Catholics are similar to black Protestants.

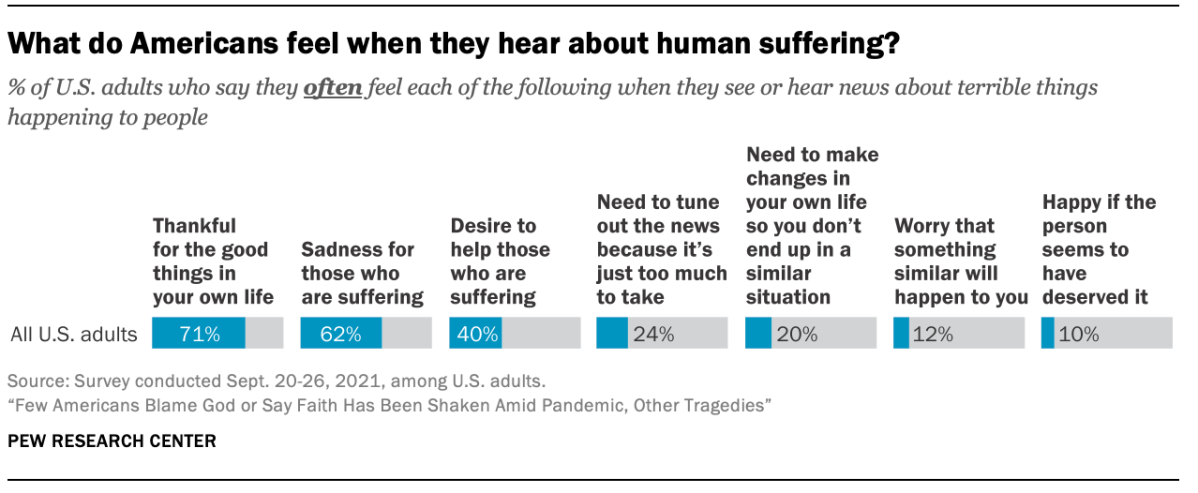

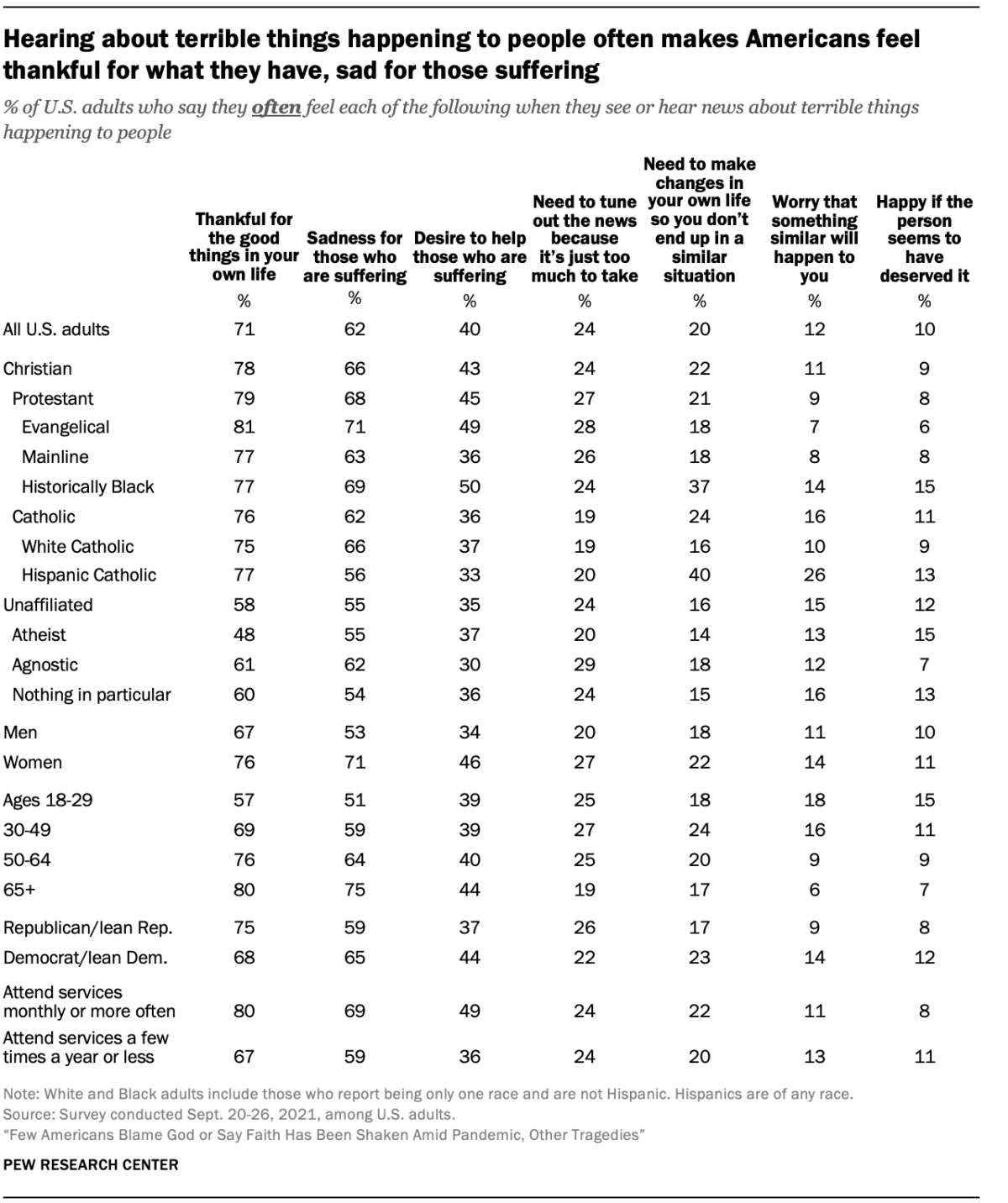

Finally, when it comes to emotional responses, Pew found:

- 2 in 10 American adults get angry with God because of suffering.

- 2 in 10 believe suffering is punishment from God.

- 1 in 10 feel schadenfreude, or happy when bad things happen to “bad people.”

Tradition has it that one day some skeptics were discussing Christianity with Voltaire, himself the prince of skeptics. He observed, “Gentlemen, it would be easy to start a new religion to compete with Christianity. All the founder would have to do is die and then be raised from the dead.”

Tradition has it that one day some skeptics were discussing Christianity with Voltaire, himself the prince of skeptics. He observed, “Gentlemen, it would be easy to start a new religion to compete with Christianity. All the founder would have to do is die and then be raised from the dead.”Voltaire was right. The resurrection of Jesus Christ is indeed the North Star of authentic Christianity. Martin Luther said, “He who would preach the gospel must go directly to preaching the resurrection of Christ. He who does not preach the resurrection is no apostle, for this is the chief part of our faith.… Everything depends on our retaining a firm hold on this article [of faith] in particular; for if this one totters and no longer counts, all the others will lose their value and validity.”

Saint Paul puts it this way: “If Christ is not risen, then our preaching is vain and your faith is also vain. Yes, and we are found false witnesses to God, because we have testified of God that He raised up Christ, whom He did not raise up—if in fact the dead do not rise.… And if Christ is not risen, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins! Then also those who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. If in this life only we hope in Christ, we are of all men the most pitiable” (1 Cor. 15:14–19, NKJV).

The Resurrection stands at the very center of the apostolic witness. It is God’s creation power open to all who would but believe. It is our hope unto eternal life.

He is risen! The Lord is risen indeed.

Adapted from an article by Charles W. Keysor, pastor, Countryside Evangelical Covenant Church, Clearwater, Florida.

The problem of evil is “the hardest thing to confront as a Christian philosopher,” Alvin Plantinga told CT after winning the Templeton Prize in 2017 for his influential work to bring theism back into the study of philosophy.

“It’s really hard to understand, even after thinking about it for many years, why God would permit so much evil in the world. You have to wonder, ‘Why does God permit that?’” said the Christian philosopher in a podcast interview. “I think we don’t know. I don’t think there’s a good answer to that. There are lots of suggestions people have made, theories people have tried out. But I don’t think any of them are very satisfactory. At the end, this is a puzzle.”

Prior to the pandemic, CT examined why viruses don’t disprove God’s goodness.

The Pew survey released today also asked Americans 20 questions about heaven and hell and other afterlife topics.

Editor’s note: This post will be updated.