African Americans are among the most devout groups in religion research, often outranking other demographics in areas like religious practice, attendance, and belief.

As a result, some predicted that young Black adults would resist the moves away from faith seen among white millennials.

Even with all the shifts in the faith landscape over the past several years, Black Americans remain more religious than other groups and more likely than the average American to stay in the tradition they were raised in, according to a massive report released by Pew Research Center last year.

But black “nones” are growing. With 3 in 10 adults in the US claiming no religious affiliation on surveys, the rise of the nones has touched every corner of American society.

Over more than a decade, the share of Black Americans who say that they have no religious affiliation has risen more dramatically than whites, Hispanics, or Asians.

But looking beyond that statistic, we see a much more nuanced view of Black religion in the United States.

Once upon a time, Shirley MacLaine was just an actress. But that was before her book, Out on a Limb, which documents for the dubious her spiritled travels into the unseen dimensions of time and space. Now Dancing in the Light shows MacLaine rushing headlong into the darkness, chanting mantras and using crystals for spiritual power.As preposterous as all this may sound, MacLaine’s New Age gospel has millions of adherents—and is anything but new. Rooted in the so-called ancient wisdom (a creative mixing of Eastern mysticism with Western occultism), the New Age movement is simply pantheism with a twentieth-century facelift. However, since the sixties, its influence has affected every major facet of contemporary culture.And that’s why we felt it was time to look critically at the philosophical/theological basis of this confusing—and popular—movement. Applying the critical ink is Canadian author Bob Burrows, editor of publications for the Spiritual Counterfeits Project (SCP). It was Bob’s essay on the New Age in a recent SCP Newsletter that initially caught the attention of CT associate editor David Neff, who called the SCP offices in California and made the assignment.Bob’s response was, well, overwhelming: 35 typed pages. Whittling down such a mass of words is not usually a problem for someone who carries a blue pencil the size of David’s. But alas, he had 35 well-reasoned, well-written pages to edit down to 25. The cuts came hard. But what was spared “Neff’s knife” is a cover story addressing what Burrows calls “man’s major preoccupation throughout history”; namely, his desire to be in control of his universe—his desire to be a god.HAROLD SMITH, Managing Editor

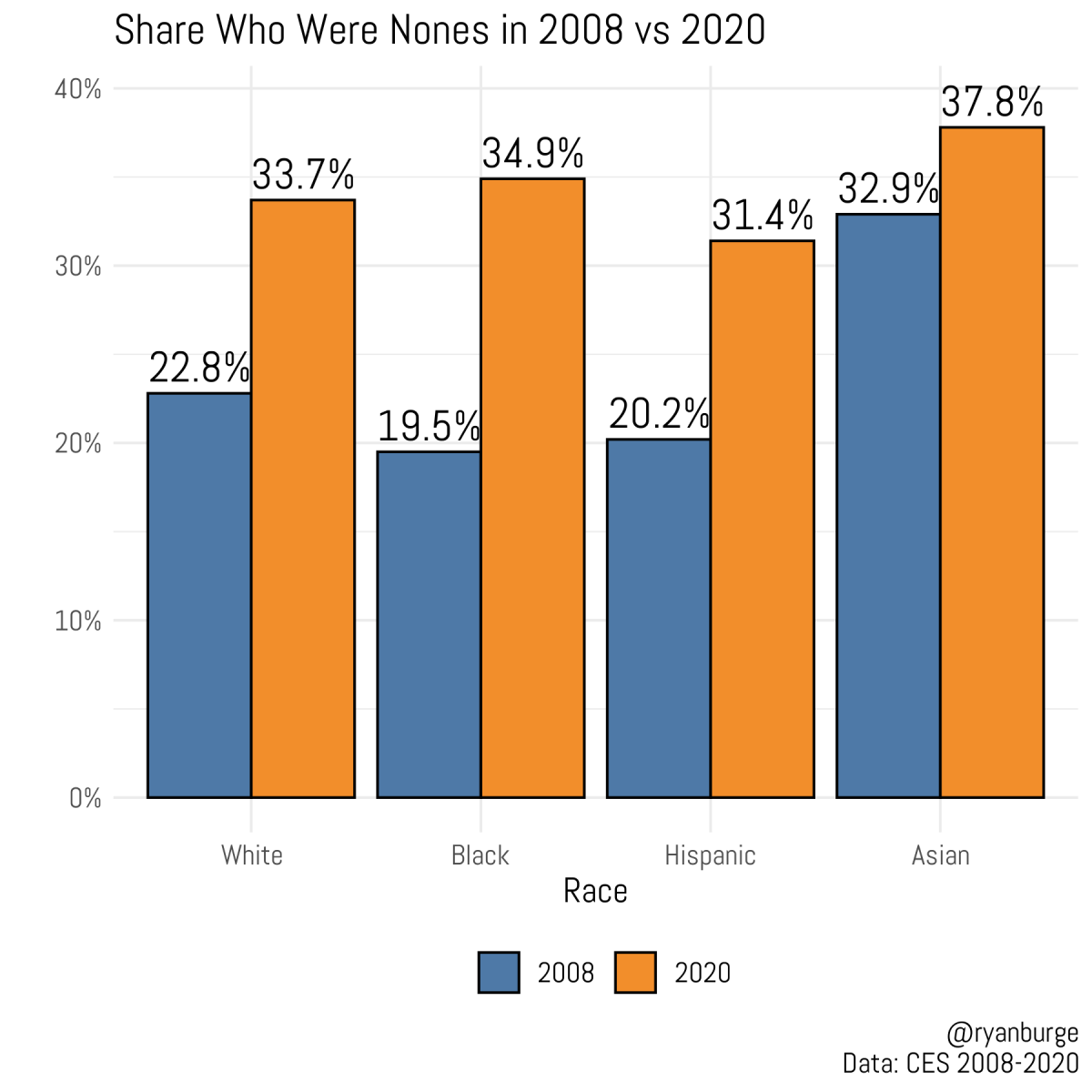

Once upon a time, Shirley MacLaine was just an actress. But that was before her book, Out on a Limb, which documents for the dubious her spiritled travels into the unseen dimensions of time and space. Now Dancing in the Light shows MacLaine rushing headlong into the darkness, chanting mantras and using crystals for spiritual power.As preposterous as all this may sound, MacLaine’s New Age gospel has millions of adherents—and is anything but new. Rooted in the so-called ancient wisdom (a creative mixing of Eastern mysticism with Western occultism), the New Age movement is simply pantheism with a twentieth-century facelift. However, since the sixties, its influence has affected every major facet of contemporary culture.And that’s why we felt it was time to look critically at the philosophical/theological basis of this confusing—and popular—movement. Applying the critical ink is Canadian author Bob Burrows, editor of publications for the Spiritual Counterfeits Project (SCP). It was Bob’s essay on the New Age in a recent SCP Newsletter that initially caught the attention of CT associate editor David Neff, who called the SCP offices in California and made the assignment.Bob’s response was, well, overwhelming: 35 typed pages. Whittling down such a mass of words is not usually a problem for someone who carries a blue pencil the size of David’s. But alas, he had 35 well-reasoned, well-written pages to edit down to 25. The cuts came hard. But what was spared “Neff’s knife” is a cover story addressing what Burrows calls “man’s major preoccupation throughout history”; namely, his desire to be in control of his universe—his desire to be a god.HAROLD SMITH, Managing EditorIn 2008, 22 percent of all Americans who participated in the Cooperative Election Study indicated that they were atheist, agnostic, or described their religion as “nothing in particular.” Just 12 years later, the share of nones rose to just over 34 percent. When that rise is tracked across different racial groups, different patterns emerge.

For instance, white respondents tracked the national average nearly perfectly, with 23 percent nones in 2008, rising to 34 percent by 2020. Among Hispanic respondents. There was an increase of 11 percentage points, but for Asians—who already had the highest levels of religious unaffiliation—it was much more modest at just about 5 percent.

Among African Americans, the increase in the share of the nones was much larger, more than 15 percentage points. In 2008, African Americans were the least likely to be nones (19.5%), but by 2020 they were more likely to say that they had no religious affiliation than white or Hispanic respondents (34.9%).

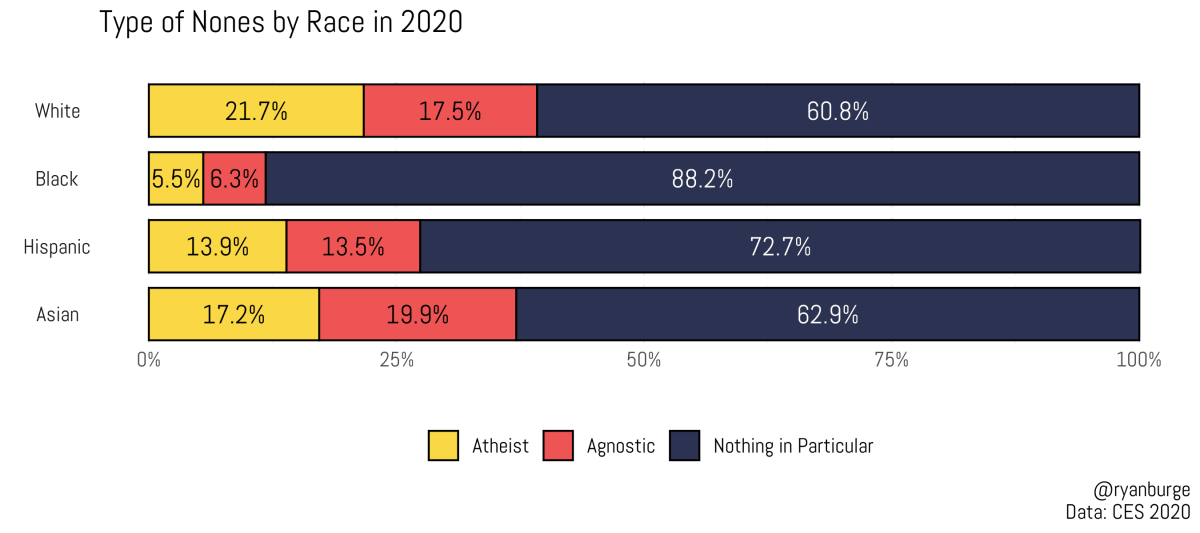

But beyond that top-level statistic, the story among African Americans is much more subtle and nuanced. As previously mentioned, three response options are combined to make up the nones: atheists, agnostics, and those who say that they have no religion in particular.

Ever since giving to the needy became chic in Hollywood, we’ve been treated to a billion-dollar bonanza of celebrities, benefit records, and sad-eyed Ethiopian children.It was Band-Aid, the British concert to help starving children, that started the aid bandwagon rolling. Later came Live Aid, a marathon rock concert simulcast from London and Philadelphia.Thereafter, since aid had become so fashionable, came Fashion Aid, a charity evening of haute couture in London, followed by a Hollywood benefit for Mexican earthquake victims. There was Farm Aid to focus on the plight of American farmers; and an AIDS benefit after Rock Hudson’s death could only be thought of as AIDS aid.Three more compassion extravaganzas occurred in May. Hands Across America linked a human chain from Los Angeles to New York to raise 0 million for domestic homelessness and hunger.The Freedom Festival raised money for Vietnam veterans; and then there’s my favorite, Sport Aid, which began with a runner leaving Ethiopia with a torch lighted from a refugee’s campfire. He jogged to several European cities; then this tireless athlete flew to New York, torch in hand (I can’t help wondering about those “no smoking” signs in airplane cabins); there he lighted a flame in Manhattan’s United Nations Plaza, which signaled the start of simultaneous 10-kilometer runs around the world. The plan, said organizer Bob Geldof, mastermind of Live Aid, was to raise money to fight disease and hunger in Africa.While we all agree that helping starving people is a good thing, this sudden aid frenzy does raise some practical questions.First, in an industry where publicity is the ticket to success, one may be excused for wondering if celebrity participation in such well-heralded events is altogether altruistic. The “We Are the World” video, which has sold millions of copies, reminds us less of starving children than of the great humanitarianism of its showcase of rock idols. The goals may be worthy, but such slickly publicized charity can only bring to mind biblical warnings against hiring trumpeters—or camera crews—to record one’s good deeds.We might put aside petty suspicions about motives if only we knew that those in need were being helped. But this raises a second question.The New Republic reports that while USA for Africa, the organization behind Live Aid, appeals for contributions to help the starving, 55 percent of its money is instead waiting to be spent on “recovery and long-term development projects,” something celebrity efforts may be ill-equipped to pull off.Of the million raised by Live Aid and Band Aid, Newsweek says only million has gone to emergency relief. Another .5 million has been spent on trucks and ships to haul supplies; million has been earmarked for projects like bridges in Chad. The rest sits in bank accounts somewhere.Unfortunately, there is an apolitical illusion at work in much of the celebrity aid: the belief that government or establishment relief agencies are unnecessary, and all we need is Bruce Springsteen.But even noncontroversial goals such as feeding the hungry can get bogged down in squabbles over how money and food should be distributed, or stymied at the Marxist-controlled ports of Ethiopia. Let’s not kid ourselves: just because the fans in London or Philadelphia go home satisfied doesn’t meanMy third question concerns the amoral illusion in all this. Consider the highlight of the Live Aid concert, the steamy duet of rock stars Mick Jagger and Tina Turner.Jagger’s 20-year career includes such dubious hits as “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Between the Sheets.” Tina Turner, clad in black leather for the show, claims a number of prior lives, including a stint as the ancient Egyptian queen Hatshepsut. Their erotic tangle was surely as much an appeal to the lust of the crowd as to help for the hungry.There seems to be no sense of the incompatibility of noble ends and ignoble means. “A good tree cannot produce bad fruit, nor can a rotten tree produce good fruit,” Jesus said flatly. There is a connection between charity, in the biblical sense, and virtue. If promoting lust is wrong, then we must ask: Can the good of feeding the hungry be accomplished by evil?Rock promoter Bill Graham says of celebrity aid, “It’s an incredible power, knowing on any given day you can raise a million dollars.” Newsweek observes, “Perhaps that is why Live Aid and Farm Aid were such oddly upbeat exercises in self-congratulation. An industry was celebrating its power. Far from challenging the complacency of an audience, such mega-events reinforce it.… Now, by watching a pop-music telethon and making a donation … fans can enjoy vicariously a sense of moral commitment.”All this leads to the most dangerous illusion of all: the impression that our celebrity idols discovered the hunger crisis, and now, with their prime-time specials, have solved it.Jagger, Turner, and company notwithstanding, feeding the hungry did not begin with Live Aid. Organizations like Catholic Relief Services, World Vision, the Salvation Army, and millions of local churches have long been feeding the hungry—without the razzle-dazzle so recently discovered by the rich and famous. Incentives have not been albums and the chance to see celebrities grind up against one another, but obedience to Christ’s commands.Bob Geldof recently announced that the Band-Aid campaign, its mission accomplished, will close down by December. “It’s like a shooting star,” he enthused.” … [F]or once … absolutely good and absolutely incorruptible came and went and worked.”I wonder. Shooting stars don’t feed hungry multitudes. The real tragedy of celebrity aid would be if the public believes that the need is over when the curtain comes down in Hollywood.For the problem of hunger will still be with us—and so will Christ’s command to feed the hungry.

Ever since giving to the needy became chic in Hollywood, we’ve been treated to a billion-dollar bonanza of celebrities, benefit records, and sad-eyed Ethiopian children.It was Band-Aid, the British concert to help starving children, that started the aid bandwagon rolling. Later came Live Aid, a marathon rock concert simulcast from London and Philadelphia.Thereafter, since aid had become so fashionable, came Fashion Aid, a charity evening of haute couture in London, followed by a Hollywood benefit for Mexican earthquake victims. There was Farm Aid to focus on the plight of American farmers; and an AIDS benefit after Rock Hudson’s death could only be thought of as AIDS aid.Three more compassion extravaganzas occurred in May. Hands Across America linked a human chain from Los Angeles to New York to raise 0 million for domestic homelessness and hunger.The Freedom Festival raised money for Vietnam veterans; and then there’s my favorite, Sport Aid, which began with a runner leaving Ethiopia with a torch lighted from a refugee’s campfire. He jogged to several European cities; then this tireless athlete flew to New York, torch in hand (I can’t help wondering about those “no smoking” signs in airplane cabins); there he lighted a flame in Manhattan’s United Nations Plaza, which signaled the start of simultaneous 10-kilometer runs around the world. The plan, said organizer Bob Geldof, mastermind of Live Aid, was to raise money to fight disease and hunger in Africa.While we all agree that helping starving people is a good thing, this sudden aid frenzy does raise some practical questions.First, in an industry where publicity is the ticket to success, one may be excused for wondering if celebrity participation in such well-heralded events is altogether altruistic. The “We Are the World” video, which has sold millions of copies, reminds us less of starving children than of the great humanitarianism of its showcase of rock idols. The goals may be worthy, but such slickly publicized charity can only bring to mind biblical warnings against hiring trumpeters—or camera crews—to record one’s good deeds.We might put aside petty suspicions about motives if only we knew that those in need were being helped. But this raises a second question.The New Republic reports that while USA for Africa, the organization behind Live Aid, appeals for contributions to help the starving, 55 percent of its money is instead waiting to be spent on “recovery and long-term development projects,” something celebrity efforts may be ill-equipped to pull off.Of the million raised by Live Aid and Band Aid, Newsweek says only million has gone to emergency relief. Another .5 million has been spent on trucks and ships to haul supplies; million has been earmarked for projects like bridges in Chad. The rest sits in bank accounts somewhere.Unfortunately, there is an apolitical illusion at work in much of the celebrity aid: the belief that government or establishment relief agencies are unnecessary, and all we need is Bruce Springsteen.But even noncontroversial goals such as feeding the hungry can get bogged down in squabbles over how money and food should be distributed, or stymied at the Marxist-controlled ports of Ethiopia. Let’s not kid ourselves: just because the fans in London or Philadelphia go home satisfied doesn’t meanMy third question concerns the amoral illusion in all this. Consider the highlight of the Live Aid concert, the steamy duet of rock stars Mick Jagger and Tina Turner.Jagger’s 20-year career includes such dubious hits as “Sympathy for the Devil” and “Between the Sheets.” Tina Turner, clad in black leather for the show, claims a number of prior lives, including a stint as the ancient Egyptian queen Hatshepsut. Their erotic tangle was surely as much an appeal to the lust of the crowd as to help for the hungry.There seems to be no sense of the incompatibility of noble ends and ignoble means. “A good tree cannot produce bad fruit, nor can a rotten tree produce good fruit,” Jesus said flatly. There is a connection between charity, in the biblical sense, and virtue. If promoting lust is wrong, then we must ask: Can the good of feeding the hungry be accomplished by evil?Rock promoter Bill Graham says of celebrity aid, “It’s an incredible power, knowing on any given day you can raise a million dollars.” Newsweek observes, “Perhaps that is why Live Aid and Farm Aid were such oddly upbeat exercises in self-congratulation. An industry was celebrating its power. Far from challenging the complacency of an audience, such mega-events reinforce it.… Now, by watching a pop-music telethon and making a donation … fans can enjoy vicariously a sense of moral commitment.”All this leads to the most dangerous illusion of all: the impression that our celebrity idols discovered the hunger crisis, and now, with their prime-time specials, have solved it.Jagger, Turner, and company notwithstanding, feeding the hungry did not begin with Live Aid. Organizations like Catholic Relief Services, World Vision, the Salvation Army, and millions of local churches have long been feeding the hungry—without the razzle-dazzle so recently discovered by the rich and famous. Incentives have not been albums and the chance to see celebrities grind up against one another, but obedience to Christ’s commands.Bob Geldof recently announced that the Band-Aid campaign, its mission accomplished, will close down by December. “It’s like a shooting star,” he enthused.” … [F]or once … absolutely good and absolutely incorruptible came and went and worked.”I wonder. Shooting stars don’t feed hungry multitudes. The real tragedy of celebrity aid would be if the public believes that the need is over when the curtain comes down in Hollywood.For the problem of hunger will still be with us—and so will Christ’s command to feed the hungry.When the types of nones are calculated for each racial group, a much different picture emerges. While the nones have gained the most ground among African Americans, that does not mean that there are many more Black atheists and agnostics than there were in 2008.

In fact, among Black nones, just 6 percent of them identify as atheist and another 6 percent say that they are agnostic. That means that nearly 9 in 10 Black nones are nothing in particular. That’s much higher than any other racial group.

For instance, just 61 percent of white nones are nothing in particular, 63 percent of Asians, and 73 percent of Hispanics. Clearly, when African Americans leave religion behind, they are very reluctant to embrace the labels of atheist or agnostic.

There’s a chapter in my book about the religious unaffiliated titled “All Nones Are Not Created Equal” about how different those three groups are really based on a number of demographic factors, but one stands out. Among those who said that they were atheists in 2010, just 3 percent identified with a religion in 2014. Among agnostics, it was 6.5 percent who embraced a religious tradition. For nothing in particulars, it was nearly 25 percent.

Thus, the data indicates that Black nones have a stronger faith background and are much more likely to embrace religion in the future than nones of other racial groups.

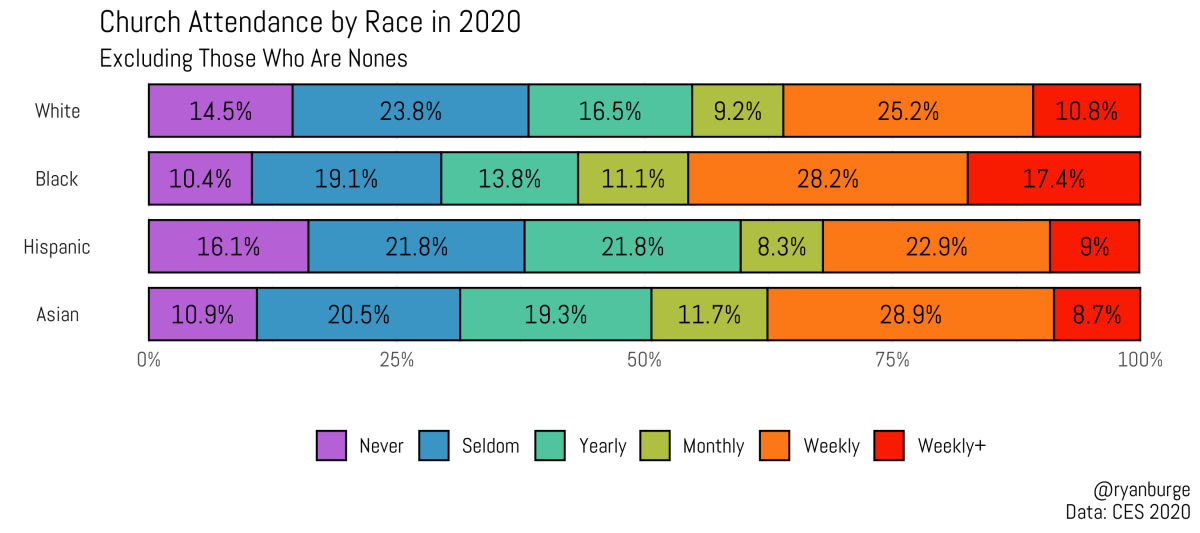

Despite rise of religious unaffiliation, Black Americans who still identify with a religious tradition are staying faithful. They continue to report much higher levels of church attendance than other races.

For instance, in 2020, nearly 46 percent of religious Black people describe their church attendance as weekly or more than once per week. For white respondents, just 36 percent attended weekly or more. For Hispanics that percentage was 32 percent and for Asians it was 38 percent. On the other end of the spectrum, less than 30 percent of Black respondents said that they attended church less than once per year. That’s nearly 10 points lower than whites in the sample.

While the share of the nones has nearly doubled in the past 12 years among Black Americans, there’s still plenty of evidence in the data that they are more open to religion than other racial groups.

In 2020, just 2 percent of all African Americans said that they were atheists, and another 2 percent were agnostics, compared to 31 percent who said that they had no religion in particular.

As previously mentioned, “nothing in particulars” are 4 to 8 times more likely to come back to religion over time compared to atheists and agnostics. That means that many of them may return to religion over time. And among those who still identify with a religious tradition, Black Americans are more active in their religious communities than any other racial group.

Even in an age of rapid secularization, the Black church still plays a crucial role in the lives of African Americans throughout the US. For Black pastors, the mission field is incredibly ripe, and many are heeding this call.

The North American Mission Board has worked in partnership with the SBC’s National African American Fellowship with the SBC’s National African American Fellowship to plant churches in underserved African American communities across the United States, and the first fruits of those efforts are already beginning to emerge. New efforts by Crete Collective and Dhati Lewis’s forthcoming BLVD are also turning attention to such communities.

Jude 3 Project, an apologetics ministry among Black Christians led by Lisa Fields, has a discussion series called “Why I Don’t Go,” engaging and listening to African Americans who have left the church.

“Classical and traditional apologetics goes a lot to proving the existence of God. When you know the Black context, you realize most Black people believe that a God exists or a higher power exist,” Fields said in a podcast interview last year.

“Black atheism is growing, but it’s still a minority of Black people. So we have to figure out what black people are navigating, what are the challenges, and meet them there.”