As I was growing up in Malaysia, my parents would send me to Mandarin lessons after school. Despite their best efforts, I was particularly resistant to learning Chinese. Consequently, most Mandarin lessons went in one ear and out the other, particularly the ones about chengyu (成语).

The four-character idioms called chengyu are a popular way in Mandarin to state a meaning, moral, or teaching. Part of their appeal lies in their ability to express powerful ideas in a concise, proverbial manner.

In theory, each chengyu I labored to remember should have pressed the collective wisdom of our ancestors into my reluctant heart. But it was a lost cause. After all, how could a child reared on American cartoons and comics possibly value esoteric phrases like meng mu san qian (孟母三迁), which extols how Chinese philosopher Mencius’s mother moved to different neighborhoods three times to improve her child’s chances of success? My family’s move abroad when I was 10 years old ended further hopes of progress.

Now, pastoring a Chinese church in New Zealand and rediscovering my mother tongue as an adult, I still struggle to memorize chengyu. But when my virtual Mandarin-language teacher, who is based in China, brings up these idioms, his eyes brim with excitement as he shares not only their vernacular use but also their fascinating backstories.

Chengyu sum up stories, principles, or lessons from Chinese history. Some retell humorous folktales as proverbs for daily life. Others connect China’s 3,500-year-old written history, including pre-Qin dynasty writings like Confucian poetry classic Shijing (诗经), to our present-day hopes and anxieties.

Both ancient and modern chengyu are used in written conversations and taught in classes today to provide insights into the Chinese worldview, which values observing filial piety, prioritizing collective benefit over an individual’s, and honoring our ancestors’ wisdom. To memorize and use chengyu is to enact a “cultural performance” that enables us to develop or maintain relationships in that particular milieu.

If chengyu are like portraits that illustrate moral or ethical principles, how can they contribute to fresh ways of understanding Scripture? In my Mandarin lessons, I’ve learned that the Book of Philippians is a favorite among Christians in China. Like the church in Philippi, they are considered outsiders in a society that demands loyalty to a “great leader” and the official party line.

For a relatively short letter, Philippians speaks a lot about becoming wise. The Greek verb phroneō (φρονέω), which means “to have understanding” and to “be wise,” appears ten times in this letter (compared to once each in Galatians and Colossians and nine times in the much longer Romans). The meaning of this word extends beyond intellectual assent. It invites us to cultivate an attitude, to carefully consider a scenario, to set our minds on a way of thinking.

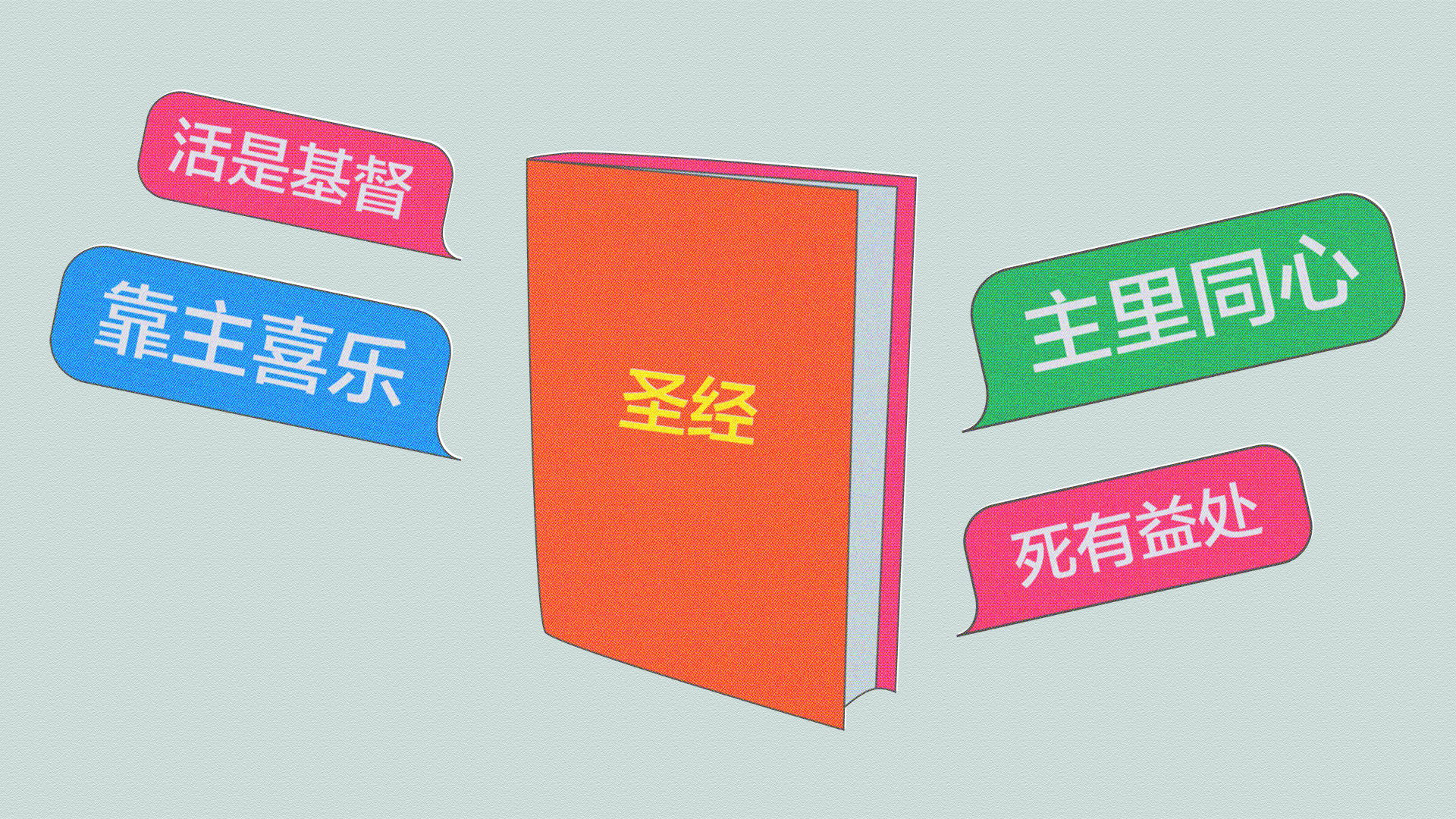

“Thinking” with the Philippians, then, is like chewing on chengyu. Through reading the Chinese Bible, I’ve discovered three particularly punchy chengyu that are helpful reminders in living out our faith every day.

Pursuing unity

In Philippians 4:2, Paul pleads with Euodia and Syntyche, members of the church in Philippi, to reconcile by asking them to “be of the same mind in the Lord.” In the Chinese Union Version (CUV), this phrase is translated into four characters: zhu li tong xin (主里同心). Mandarin readers will know that the second half of the phrase means having the “same heart.” In reading this phrase as chengyu, we see that Paul encourages them not to simply concede mentally but to seek unity of heart in the Lord.

The nature of Euodia and Syntyche’s conflict escapes us. Were they arguing over money or missions strategy? Did they disagree on whether winsome speech or righteous anger was the best response to “enemies of the cross” (Phil. 3:18)? Or, as a youth pastor once joked, did they fall for the same guy?

Only by re-envisioning their seemingly irreconcilable differences through the eyes of Christ can two (or more) quarrelers begin to “be of the same mind in the Lord.” It’s the same attitude that Paul mentions earlier in the letter when encouraging brothers and sisters to be “like-minded” (2:2). It also reflects the humility that Christ exemplified as he walked toward death and resurrection (2:5–11), making reconciliation truly possible.

How many difficult conversations in church could have turned out differently had I memorized Philippians 4:2 as chengyu? Perhaps I would have sought to win over a brother in Christ and not the argument at hand or to empathize more sincerely with a sister in Christ.

Recovering joy

If seeking authentic reconciliation amid conflict isn’t a perennial issue that believers face, struggling with mental health challenges might be. In the past five years, antidepressant use has jumped 53 percent among children and teens in New Zealand. Pastors and parents feel the weight of an anxious generation fighting to experience hope and joy.

In this context, telling my congregants to “rejoice in the Lord” (Phil. 4:4) frequently feels like yet another trite, simplistic cliché. The follow-up directive to “not be anxious about anything: (4:6) is rarely more assuring.

But what if we treated this phrase as a chengyu to chew over rather than a quick fix to dispense? In Mandarin, our source of joy is placed upfront: kao zhu xi le (靠主喜乐), or “trusting the Lord, rejoice.” Read in this light, the phrase is less a command to follow (“Put on a happy face!”) and more an introduction to Someone outside ourselves whom we can rely on.

To rejoice in the Lord, we must rest in the knowledge that the most undeserved death in history is the source of our greatest joy, even as our experience of mental health challenges may continue to persist. We look to Christ, who “for the joy set before him … endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God” (Heb. 12:2). In doing so, he upends our expectations of where true joy can be found.

Paul’s life also reflects this principle of rejoicing in God through trusting in him. The apostle’s imprisonment advanced the gospel both into the highest halls of power and into the hearts of brothers and sisters now emboldened to speak the Word without fear (Phil. 1:12–14). Pondering the story behind Paul’s suffering allows us to behold the glory of Christ. So again, Paul will say, “Rejoice!”—not as a command but as a chengyu pointing to Jesus, our only source of true delight in an anxious age.

Longing for new life

Paul’s instructions to the Philippians emphasize the importance of seeking unity and joy in Christ. But the beginning of his letter highlights a foundational belief that undergirds his exhortations: “For to me, to live is Christ and to die is gain” (1:21). In Mandarin, this paradoxical phrase can be rendered as a pair of chengyu: huo shi ji du, si you yi chu (活是基督,死有益处).

The Mandarin word for “profit” (益处) particularly resonates with the Chinese culture’s penchant for accruing material wealth. The word reappears when Paul lists his impeccable credentials and earthly achievements like a chartered accountant (3:4–6), only to say, “But whatever were gains (or profits) to me I now consider loss for the sake of Christ” (3:7). In other words, only Jesus is priceless. Flush the rest away.

Now that I have children of my own, I feel the sinful urge to define profit and gain like Mencius’s mother once did: a college acceptance, an honorable career, a family, and kids. Yet the gospel gives us a better way to see profit and loss. Because of Christ’s death for our sins and life beyond the empty tomb, life in Christ is of invaluable worth, and death is merely a doorway to everlasting gain.

One way I’ve recently been trying store up Philippians 1:21 in my heart is to visualize and pray for brothers and sisters who cling to this proverb from countries that are hostile to their very existence. I think of my Mandarin teacher’s hope for repentance and revival in his house church and how this chengyu is a daily reality for him. I recall a testimony of a formerly devout Muslim who held intense hatred for Christians but later accepted Jesus as his personal Savior.

As Simo Ralevic, a Serbian Christian, shared, “For Christians in the West, I wish you persecution. Then you will know the sweetness of Christ. … Out[side] of Christ is only death. In Christ is life.” Encountering stories of believers facing persecution in the global church encourages us to take up our crosses daily, precisely where God has placed us.

Reading contextually

Wider culture wars have conditioned us to be wary of cultural interpretations of the Bible. In Reading Romans with Eastern Eyes, missiologist Brad Vaughn (formerly known as Jackson Wu) rightly warns against blindly using “contextual” interpretations to co-opt Scripture for political or social purposes.

But approaching Philippians with Eastern eyes need not jettison our theological heritage. It can draw us toward drinking more deeply from the inexhaustible riches of Christ, our wisdom (1 Cor. 1:30). I’m confident God does not waste anything: not my mixed heritage, my childhood struggle to memorize chengyu, or my Mandarin-language classes.

Theologizing between cultures is like sitting in an estuary, a tidal space where the saltwater of open sea and the freshwater of inland rivers mix, according to Chloe Sun, professor of Old Testament at Logos Evangelical Seminary. As water currents converge and diverge within the same transitional space, they form a rich and fertile habitat for maritime life. Likewise, when we read Scripture in liminal ways, we learn new ways of telling the timeless story of a wise and loving Savior awaiting his citizens of heaven (Phil. 3:20).

God’s grace frees me to mine the depths of Scripture through my Western roots, while appreciating how Eastern ways of collecting and presenting wisdom can contextualize the message of Christ. My Mandarin teacher’s house church in China and my immigrant church in New Zealand may be continents apart, but through our weekly lessons, our stories interweave and a forgotten tongue reawakens. As we find chengyu—or “true words” in Mandarin—in Philippians, our hearts grow wise.

William HC is the pastor of a Chinese church in Auckland, New Zealand. He uses a pseudonym, as he ministers and supports believers in sensitive contexts.